Case 1:05-Cv-02267-JFM Document 27 Filed 01/31/06 Page 1 of 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English, French, and Spanish Colonies: a Comparison

COLONIZATION AND SETTLEMENT (1585–1763) English, French, and Spanish Colonies: A Comparison THE HISTORY OF COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA centers other hand, enjoyed far more freedom and were able primarily around the struggle of England, France, and to govern themselves as long as they followed English Spain to gain control of the continent. Settlers law and were loyal to the king. In addition, unlike crossed the Atlantic for different reasons, and their France and Spain, England encouraged immigration governments took different approaches to their colo- from other nations, thus boosting its colonial popula- nizing efforts. These differences created both advan- tion. By 1763 the English had established dominance tages and disadvantages that profoundly affected the in North America, having defeated France and Spain New World’s fate. France and Spain, for instance, in the French and Indian War. However, those were governed by autocratic sovereigns whose rule regions that had been colonized by the French or was absolute; their colonists went to America as ser- Spanish would retain national characteristics that vants of the Crown. The English colonists, on the linger to this day. English Colonies French Colonies Spanish Colonies Settlements/Geography Most colonies established by royal char- First colonies were trading posts in Crown-sponsored conquests gained rich- ter. Earliest settlements were in Virginia Newfoundland; others followed in wake es for Spain and expanded its empire. and Massachusetts but soon spread all of exploration of the St. Lawrence valley, Most of the southern and southwestern along the Atlantic coast, from Maine to parts of Canada, and the Mississippi regions claimed, as well as sections of Georgia, and into the continent’s interior River. -

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Northeast Corridor Chase, Maryland January 4, 1987

PB88-916301 NATIONAL TRANSPORT SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT REAR-END COLLISION OF AMTRAK PASSENGER TRAIN 94, THE COLONIAL AND CONSOLIDATED RAIL CORPORATION FREIGHT TRAIN ENS-121, ON THE NORTHEAST CORRIDOR CHASE, MARYLAND JANUARY 4, 1987 NTSB/RAR-88/01 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2.Government Accession No. 3.Recipient's Catalog No. NTSB/RAR-88/01 . PB88-916301 Title and Subtitle Railroad Accident Report^ 5-Report Date Rear-end Collision of'*Amtrak Passenger Train 949 the January 25, 1988 Colonial and Consolidated Rail Corporation Freight -Performing Organization Train ENS-121, on the Northeast Corridor, Code Chase, Maryland, January 4, 1987 -Performing Organization 7. "Author(s) ~~ Report No. Performing Organization Name and Address 10.Work Unit No. National Transportation Safety Board Bureau of Accident Investigation .Contract or Grant No. Washington, D.C. 20594 k3-Type of Report and Period Covered 12.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Iroad Accident Report lanuary 4, 1987 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 1*+.Sponsoring Agency Code 15-Supplementary Notes 16 Abstract About 1:16 p.m., eastern standard time, on January 4, 1987, northbound Conrail train ENS -121 departed Bay View yard at Baltimore, Mary1 and, on track 1. The train consisted of three diesel-electric freight locomotive units, all under power and manned by an engineer and a brakeman. Almost simultaneously, northbound Amtrak train 94 departed Pennsylvania Station in Baltimore. Train 94 consisted of two electric locomotive units, nine coaches, and three food service cars. In addition to an engineer, conductor, and three assistant conductors, there were seven Amtrak service employees and about 660 passengers on the train. -

Evidence from Ghanaian Railways∗

Colonial Investments and Long-Term Development in Africa: Evidence from Ghanaian Railways∗ Remi JEDWABa Alexander MORADIb a Department of Economics, George Washington University, and STICERD, London School of Economics b Department of Economics, University of Sussex This Version: October 14th, 2012 Abstract: What is the impact of colonial public investments on long-term development? We investigate this issue by looking at the impact of railway construction on economic develop- ment in Ghana. Two railway lines were built by the British to link the coast to mining areas and the hinterland city of Kumasi. Using panel data at a fine spatial level over one century (11x11 km grid cells in 1891-2000), we find a strong effect of rail connectivity on the pro- duction of cocoa, the country’s main export commodity, and development, which we proxy by population and urban growth. First, we exploit various strategies to ensure our effects are causal: we show that pre-railway transport costs were prohibitively high, we provide ev- idence that line placement was exogenous, we find no effect for a set of placebo lines, and results are robust to instrumentation and nearest neighbor matching. Second, transportation infrastructure investments had large welfare effects for Ghanaians during the colonial period. Colonization meant both extraction and development in this context. Third, railway con- struction had a persistent impact: railway cells are more developed today despite a complete displacement of rail by other means of transport. We investigate the various channels of path dependence, including demographic growth, industrialization or infrastructure investments. Keywords: Colonialism; Africa; Transportation Infrastructure; Trade JEL classification: F54; O55; O18; R4; F1 ∗Remi Jedwab, George Washington University and STICERD, London School of Economics (e-mail: [email protected]). -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

Federal Railroad Administration Fiscal Year 2017 Enforcement Report

Federal Railroad Administration Fiscal Year 2017 Enforcement Report Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Summary of Inspections and Audits Performed, and of Enforcement Actions Recommended in FY 2017 A. Railroad Safety and Hazmat Compliance Inspections and Audits 1. All Railroads and Other Entities (e.g., Hazmat Shippers) Except Individuals 2. Railroads Only B. Summary of Railroad Safety Violations Cited by Inspectors, by Regulatory Oversight Discipline or Subdiscipline 1. Accident/Incident Reporting 2. Grade Crossing Signal System Safety 3. Hazardous Materials 4. Industrial Hygiene 5. Motive Power and Equipment 6. Railroad Operating Practices 7. Signal and train Control 8. Track C. FRA and State Inspections of Railroads, Sorted by Railroad Type 1. Class I Railroads 2. Probable Class II Railroads 3. Probable Class III Railroads D. Inspections and Recommended Enforcement Actions, Sorted by Class I Railroad 1. BNSF Railway Company 2. Canadian National Railway/Grand Trunk Corporation 3. Canadian Pacific Railway/Soo Line Railroad Company 4. CSX Transportation, Inc. 5. The Kansas City Southern Railway Company 6. National Railroad Passenger Corporation 7. Norfolk Southern Railway Company 8. Union Pacific Railroad Company III. Summaries of Civil Penalty Initial Assessments, Settlements, and Final Assessments in FY 2017 A. In General B. Summary 1—Brief Summary, with Focus on Initial Assessments Transmitted C. Breakdown of Initial Assessments in Summary 1 1. For Each Class I Railroad Individually in FY 2017 2. For Probable Class II Railroads in the Aggregate in FY 2017 3. For Probable Class III Railroads in the Aggregate in FY 2017 4. For Hazmat Shippers in the Aggregate in FY 2017 5. -

Freedom Trail N W E S

Welcome to Boston’s Freedom Trail N W E S Each number on the map is associated with a stop along the Freedom Trail. Read the summary with each number for a brief history of the landmark. 15 Bunker Hill Charlestown Cambridge 16 Musuem of Science Leonard P Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge Boston Harbor Charlestown Bridge Hatch Shell 14 TD Banknorth Garden/North Station 13 North End 12 Government Center Beacon Hill City Hall Cheers 2 4 5 11 3 6 Frog Pond 7 10 Rowes Wharf 9 1 Fanueil Hall 8 New England Downtown Crossing Aquarium 1. BOSTON COMMON - bound by Tremont, Beacon, Charles and Boylston Streets Initially used for grazing cattle, today the Common is a public park used for recreation, relaxing and public events. 2. STATE HOUSE - Corner of Beacon and Park Streets Adjacent to Boston Common, the Massachusetts State House is the seat of state government. Built between 1795 and 1798, the dome was originally constructed of wood shingles, and later replaced with a copper coating. Today, the dome gleams in the sun, thanks to a covering of 23-karat gold leaf. 3. PARK STREET CHURCH - One Park Street, Boston MA 02108 church has been active in many social issues of the day, including anti-slavery and, more recently, gay marriage. 4. GRANARY BURIAL GROUND - Park Street, next to Park Street Church Paul Revere, John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and the victims of the Boston Massacre. 5. KINGS CHAPEL - 58 Tremont St., Boston MA, corner of Tremont and School Streets ground is the oldest in Boston, and includes the tomb of John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. -

Patriotism and Honor: Veterans of Dutchess County, New York

Patriotism and Honor: Veterans of Dutchess County, New York Dutchess County Historical Society 2018 Yearbook • Volume 97 Candace J. Lewis, Editor Dutchess County Historical Society The Society is a not-for-profit educational organization that collects, preserves, and interprets the history of Dutchess County, New York, from the period of the arrival of the first Native Americans until the present day. Publications Committee: Candace J. Lewis, Ph.D., Editor David Dengel, Dennis Dengel, John Desmond, Roger Donway, Eileen Hayden, Julia Hotton, Bill Jeffway, Melodye Moore, and William P. Tatum III Ph.D. Designer: Marla Neville, Main Printing, Poughkeepsie, New York mymainprinter.com Printer: Advertisers Printing, Saint Louis, Missouri Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook 2018 Volume 97 • Published annually since 1915 Copyright © by Dutchess County Historical Society ISSN: 0739-8565 ISBN: 978-0-944733-13-4 Front Cover: Top: Young men of Dutchess County recently transformed into soldiers. On the steps of the Armory, Poughkeepsie, New York. 1917. Detail. Bottom: Men, women, and children walk along the railroad tracks in Poughkeepsie at lower Main Street, seeing off a contingent of soldiers as they entrain for war. 1918. Back Cover: Left: Nurses from around the country march in the parade of April 6, 1918. Detail. Middle: A “patriotic pageant,l” performed by children. April 1918. Right: Unidentified individual as he gets ready to “entrain” in the separate recruitment of African Americans. 1918, Detail. All Photographs by Reuben P. Van Vlack. Collection of the Dutchess County Historical Society. The Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook does not assume responsibility for statements of fact or opinion made by the authors. -

Fourth Avenue Meeting Fourth Avenue

Downtown Pittsburgh Walking Tour 17 Centennial Building 241 Fourth Avenue Meeting Fourth Avenue N Situated on a peninsula jutting into an intersection of rivers, We do not know the architect of this building of 1876, but #location the composition of the façade is rather sophisticated: wall Smithfield Street the city of 305,000 is gemlike, surrounded by bluffs and bright yellow bridges streaming into its heart. planes advance and recede beneath a heavy, elaborate cornice. 2 1 “Pittsburgh’s cool,” by Josh Noel, Chicago Tribune, Jan. 5, 2014 18 Investment Building (Insurance Exchange) 235–239 Fourth Avenue 5 6 FREE TOURS This 1927 work of John M. Donn, a Washington, D.C. 7 architect, is between two buildings of the same approximate 10 Old Allegheny County Jail Museum 8 façade dimensions, but they were built about 25 years earlier. Open Mondays through October (11:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.) Terra cotta has yielded to limestone, and a darker and more 13 12 9 15 16 (except court holidays) textured brick is in fashion; simplicity and lightness of form Wood Street Downtown Pittsburgh: Guided Walking Tours and detailing are evident. At the top, notice the corners 14 Every Friday, May through September (Noon to 1:00 p.m.) e chamfered with obelisk-like elements. e u u e n n 17 u e e n v v e DOWNTOWN’S BEST A v 18 A A 19 (Machesney Building) s Benedum-Trees Building h t e Special Places and Spaces in a 2-Hour Walk d r b r i 221–225 Fourth Avenue u r h o o Not free. -

Northeast Region

Northeast Region ● The 11 states that make up the US Northeast Region are Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. ● Major cities include New York City, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, and Washington D.C. ● The Northeast is bordered to the north by Canada, to the west by the Midwest, to the south by the Southeast, and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. ● Six of the states in this region are collectively known as the subregion; "New England States". They are Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont. ● The Northeast states of Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania are often referred to as the subregion; “Middle Atlantic States”. ● Washington D.C., which is not a US state, is also considered part of the Northeast region. ● The climate of the Northeast varies by season. Winters are often extremely cold; especially in the northern most states such as Maine. The regions summers are generally warm and humid. ● The mouths of four major rivers pierce the coastline to empty into the Atlantic: Delaware River, Kennebec River, Hudson River, Connecticut River. ● The Northeast has from colonial times relied on fishing and seafaring as a major source of its economic strength. Maine's excellent lobster is shipped around the nation. Boston, one of the oldest seaports in America, makes what the locals consider the finest clam chowder. ● New York City This city is one of the main tourist destinations in the world with attractions including; The Empire State Building, The Statue of Liberty, and Central Park. -

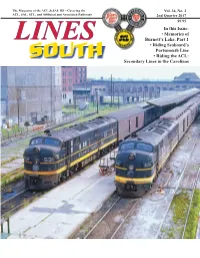

In This Issue: • Memories of Burnett's Lake, Part 1 • Riding Seaboard's

The Magazine of the ACL & SAL HS – Covering the Vol. 34, No. 2 ACL, SAL, SCL, and Affiliated and Associated Railroads 2nd Quarter 2017 $9.95 In this Issue: • Memories of LINES Burnett’s Lake, Part 1 • Riding Seaboard’s Portsmouth Line SOUTH • Riding the ACL: Secondary Lines in the Carolinas Membership Classes Regular: $35 for one year or $65 for two years. Memberships are concur- rent with the calendar year; to join or renew during the year, contact us at our LINES address below or at [email protected]. Sustaining: $60 for one year or $115 for two years. These amounts in- clude $25 and $50, respectively, in tax-deductible contributions. Century Club: $135 for one year, which includes a complimentary calen- SOUTH dar and a tax-deductible contribution of $87. We gladly accept other contributions, either financial or historical Volume 34, No. 2, 2nd Quarter 2017 materials for our archives, all of which are tax-deductible to the extent The Magazine of the ACL & SAL HS – Covering the provided by law. ACL, SAL, SCL, and Affiliated and Associated Railroads Your membership dues include quarterly issues of LINES SOUTH, participa- tion in Society-sponsored events and projects, voting rights on issues brought before the membership, and research assistance on members’ questions. LINES SOUTH STAFF Foreign (includes Canada): Membership with delivery via surface mail is Editor $60 per year or $120 for two years. For sustaining foreign memberships, add Larry Goolsby $25 for one year and $50 for two years. We can accept foreign memberships only by Visa, MasterCard, Discover, or PayPal. -

Historic Properties Identification Report

Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study E. Grand Avenue to W. Hollywood Avenue Job No. P-88-004-07 MFT Section No. 07-B6151-00-PV Cook County, Illinois Prepared For: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Department of Transportation Prepared By: Quigg Engineering, Inc. Julia S. Bachrach Jean A. Follett Lisa Napoles Elizabeth A. Patterson Adam G. Rubin Christine Whims Matthew M. Wicklund Civiltech Engineering, Inc. Jennifer Hyman March 2021 North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction and Description of Undertaking .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NLSD Area of Potential Effects (NLSD APE) ................................................................................... 1 2.0 Historic Resource Survey Methodologies ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Lincoln Park and the National Register of Historic Places ............................................................ 3 2.2 Historic Properties in APE Contiguous to Lincoln Park/NLSD ....................................................... 4 3.0 Historic Context Statements ........................................................................................................