Copyright by Jeannelle Ramirez 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josh Norek and Juan Manuel Caipo Join Onerpm; Company Establishes San Francisco Office

Josh Norek and Juan Manuel Caipo Join ONErpm; Company Establishes San Francisco Office San Francisco, CA, October 29, 2018 – Label services, rights management and distribution company ONErpm has announced the addition of Josh Norek as Director, San Francisco & U.S. Latin and Juan Manuel Caipo, A&R, North America & U.S. Latin, to the team. Their hires also mark the establishment of ONErpm’s first West Coast office, in San Francisco. This is the company’s fourth U.S. location, along with Brooklyn, Miami, and Nashville. (For hi-res version, click here: Norek, Caipo) “Josh and Juan Manuel have incredible credentials that I am certain will present new perspectives and possibilities for the growth of ONErpm in North America,” said Jason Jordan, Managing Director of US Operations. “Their varied experiences will help us maximize our catalog and artist opportunities across platforms and establish our West Coast presence.” “I am excited to be working with ONErpm founder Emmanuel Zunz and with Jason Jordan, whose visions for the future of distribution and business intelligence resonate with my own,” said Norek. “Their Latin music program is already so strong, and I’m looking forward to growing that as well as supporting ONErpm’s work in other genres.” “I believe ONErpm is changing how musicians can approach releasing their music, and I look forward to seeing what relationships we can build with artists to help them reach global audience,” said Caipo. Josh Norek has been immersed in many aspects of the Latin music industry for over twenty years. He founded and continues to serve as the president of the music royalties collection firm Regalías Digitales. -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Aye Que Rico! I Love It! I Gotta Play It! but How Do I Do It? Building a Salsa/Latin Jazz Ensemble

¡Aye que Rico! I Love It! I Gotta Play It! But How Do I Do It? Building a Salsa/Latin Jazz Ensemble By Kenyon Williams f you’ve got salsa in your sangre, you re- tion streaming video lessons on the Web, infor- member your first time—the screaming mation that was once only available to a lucky brass riffs, the electrifying piano montunos, few can now be found with ease (see list at end Ithe unbelievable energy that flowed into of article for suggested educational resources). the audience, and the timbalero, who seemed “You can’t lead any band in any style of to ride on top of it all with a smile as bright music unless you know that style of music!” as the stage lights. “The Latin Tinge,” as Jelly admonishes Latin percussion great Michael Roll Morton called it, has been a part of jazz Spiro. “People end up, in essence, failing be- ever since its inception, but it took the genius cause they don’t learn the style! The clave, bass, of such artists as Mario Bauza and Dizzy piano, and even horns, have to play a certain Gillespie in the early 1940s to truly wed way within the structure—just like the percus- the rhythms of the Caribbean with the jazz sion. If you don’t understand that, you will fail!” harmonies and instrumentation of American For an experienced jazz artist wanting to popular music styles. They created a hybrid learn or teach a new style of music for the first musical genre that would, in turn, give birth to time, this fear of failure can be crippling. -

2018-19 Season Brochure 33RD ANNUAL ARTS EVENT SEASON 2018-19 SEASON EVENTS CALENDAR

Churchill Arts Council 2018-19 Season Brochure 33RD ANNUAL ARTS EVENT SEASON 2018-19 SEASON EVENTS CALENDAR THE CHURCHILL ARTS COUNCIL is a private, non-profit arts organization PERFORMING ARTS bringing high quality arts events to Fallon, Churchill County and northern Tris Munsick & the Innocents – August 18, 2018 Nevada. For over three decades, we’ve enriched the cultural and social life of » Free In-the-Park Concert & Conversation our region by offering educational and experiential opportunities in the arts on Las Cafeteras – September 22, 2018 many levels, including: an annual performing arts series; visual art exhibitions; » Performance & Conversation literary readings and conversations with artists in all disciplines; screenings of Kugelplex – November 3, 2018 classic and foreign films; a juried local artists’ exhibition; scholarships to pursue » Performance & Conversation studies in the arts; publication of print and online visual arts catalogs as well Bill Frisell – January 26, 2019 as a monthly newsletter. We are committed to excellence in multi-disciplinary » Performance & Conversation programming as you’ll see by this overview of our 2018-19 Season. An Evening with the Arts – March 2, 2019 Sammy Miller & the Congregation – March 9, 2019 PHYSICAL ADDRESS » Performance & Post-Performance Q & A Oats Park Art Center So Percussion – April 13, 2019 151 East Park Street » Performance & Conversation Fallon, Nev. 89406 Gina Chavez & Band – May 18, 2019 » Performance & Conversation CONTACT INFORMATION Rocky Dawuni – June 15, 2019 775-423-1440 » Free In-the-Park Concert [email protected] P. O. Box 2204 VISUAL ARTS Fallon, Nev. 89407 Jay Schmidt – August 4 - November 17, 2018 www.churchillarts.org » Artist’s Talk & Reception: August 4 Kirk Robertson – August 4 - November 17, 2018 PERFORMANCE TICKETS, DATES & TIMES » Reception: August 4 All seats are reserved. -

At Home Worship Kit 24

Border wall mural that reads, “There are dreams on this side too.” CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH OF LA JOLLA AUGUST 23, 2020 HOME WORSHIP GUIDE 24 WELCOME TO WEEK 24 OF THE CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH OF LA JOLLA´S AT HOME WORSHIP EXPERIENCE. PLEASE FOLLOW THE INSTRUCTIONS IN THIS GUIDE AND UTILIZE THE AUDIO LINKS SENT TO YOU IN THE ACCOMPANYING EMAIL TO ASSIST IN YOUR WORSHIP EXPERIENCE. PLEASE PROVIDE US WITH FEEDBACK IF YOU HAVE ANY QUESTIONS OR CONCERNS. YOU CAN REACH US AT [email protected]. THIS IS CHURCH. THIS IS HOLY. THIS IS HOW WE RESPOND TO THE CHALLENGES OF OUR DAY. THIS WILL BE VERY MUCH UNLIKE WHAT YOU ARE USED TO IN CHURCH. THAT IS ON PURPOSE. THIS IS SOMETHING NEW AND BECAUSE OF THAT WE’VE TAKEN LIBERTIES TO PROVIDE YOU WITH SOMETHING TOTALLY DIFFERENT. ENJOY MUSICAL SELECTIONS YOU MIGHT NOT HAVE HEARD AT CHURCH BEFORE AND A MESSAGE UNLIKE THAT WHICH IS DELIVERED FROM THE PULPIT. CONSIDER IT AN ADVENTURE. YES, YOU ARE MAKING HISTORY TODAY. PLEASE FIND A COMFORTABLE AND COMFORTING PLACE IN YOUR HOME OR SOMEWHERE ELSE YOU FEEL SAFE. GET COMFORTABLE, POUR YOURSELF A GLASS OF SOMETHING SOOTHING AND ENJOY THIS EXPERIMENT IN WORSHIP…. WE PREPARE OUR HEARTS AND MINDS FOR WORSHIP ENJOY NINA’S PIANO SOLO BY CLICKING THE AUDIO FILE MARKED “AUDIO FILE 1” IN THE EMAIL. DURING THIS TIME LEAVE YOUR FEARS, DOUBTS, AND UNCERTAINTIES OUTSIDE THE ROOM AND BE COMPLETELY PRESENT WITH YOURSELF. BREATHE INTENTIONALLY AND FOCUS ON EACH INHALE AND EXHALE Mural in downtown Tijuana, Baja California FINDING GOD IN VOICE ENJOY BRONWYN’S SOLO BY CLICKING ON THE AUDIO FILE MARKED “AUDIO FILE 2” IN THE EMAIL. -

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian A summary of the main discussion points generated at a two-day conference organized by the Smithsonian Music group, a pan- Institutional committee, with the support of Grand Challenges Consortia Level One funding June 2012 Produced by the Office of Policy and Analysis (OP&A) Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Conference Participants ..................................................................................................................... 5 Report Structure and Other Conference Records ............................................................................ 7 Key Takeaway ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Smithsonian Music: Locus of Leadership and an Integrated Approach .............................. 8 Conference Proceedings ...................................................................................................................... 10 Remarks from SI Leadership ........................................................................................................ -

Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course

MUSIC HISTORY 13 PAGE 1 of 14 MUSIC HISTORY 13 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 13 Course Title Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice x Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis • Social Analysis x Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This course falls into social analysis and visual and performance arts analysis and practice because it shows how punk, as a subculture, has influenced alternative economic practices, led to political mobilization, and challenged social norms. This course situates the activity of listening to punk music in its broader cultural ideologies, such as the DIY (do-it-yourself) ideal, which includes nontraditional musical pedagogy and composition, cooperatively owned performance venues, and underground distribution and circulation practices. Students learn to analyze punk subculture as an alternative social formation and how punk productions confront and are times co-opted by capitalistic logic and normative economic, political and social arrangements. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Jessica Schwartz, Assistant Professor Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes x No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 2 4. -

Youth Guide to the Department of Youth and Community Development Will Be Updating This Guide Regularly

NYC2015 Youth Guide to The Department of Youth and Community Development will be updating this guide regularly. Please check back with us to see the latest additions. Have a safe and fun Summer! For additional information please call Youth Connect at 1.800.246.4646 T H E C I T Y O F N EW Y O RK O FFI CE O F T H E M AYOR N EW Y O RK , NY 10007 Summer 2015 Dear Friends: I am delighted to share with you the 2015 edition of the New York City Youth Guide to Summer Fun. There is no season quite like summer in the City! Across the five boroughs, there are endless opportunities for creation, relaxation and learning, and thanks to the efforts of the Department of Youth and Community Development and its partners, this guide will help neighbors and visitors from all walks of life savor the full flavor of the city and plan their family’s fun in the sun. Whether hitting the beach or watching an outdoor movie, dancing under the stars or enjoying a puppet show, exploring the zoo or sketching the skyline, attending library read-alouds or playing chess, New Yorkers are sure to make lasting memories this July and August as they discover a newfound appreciation for their diverse and vibrant home. My administration is committed to ensuring that all 8.5 million New Yorkers can enjoy and contribute to the creative energy of our city. This terrific resource not only helps us achieve that important goal, but also sustains our status as a hub of culture and entertainment. -

Hurray for the Riff Raff

04-03 Hurray_GP 3/14/14 3:33 PM Page 1 Sponsored by Prudential Investment Management Thursday Evening, April 3, 2014, at 8:00 Hurray for the Riff Raff Alynda Lee Segarra, Guitar and Vocals Yosi Perlstein, Fiddle and Drums Casey McAllister, Keyboards Callie Millington, Bass David Jamison, Drums This evening’s program is approximately 75 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. This performance will be streamed live at www.lincolncenter.org/watch. Major support for Lincoln Center’s American Songbook is provided by Fisher Brothers, In Memory of Richard L. Fisher; and Amy & Joseph Perella. Wine generously donated by William Hill Estate Winery, Official Wine of Lincoln Center. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano Please make certain your cellular phone, Stanley H. Kaplan Penthouse pager, or watch alarm is switched off. 04-03 Hurray_GP 3/14/14 3:33 PM Page 2 Lincoln Center Additional support for Lincoln Center’s American Upcoming American Songbook Events Songbook is provided by The Brown Foundation, Inc., in the Penthouse: of Houston, The DuBose and Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund, The Shubert Foundation, Jill and Friday Evening, April 4, at 8:00 Irwin Cohen, The G & A Foundation, Inc., Great Rebecca Naomi Jones (limited availability) Performers Circle, Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center. Saturday Evening, April 5, at 8:00 Unsung Carolyn Leigh (limited availability) Endowment support is provided by Bank of America. For tickets, call (212) 721-6500 or visit Public support is provided by the New York State AmericanSongbook.org. -

Ancient Mysteries Revealed on Secrets of the Dead A

NEW FROM AUGUST 2019 2019 NOVA ••• The in-depth story of Apollo 8 premieres Wednesday, December 26. DID YOU KNOW THIS ABOUT WOODSTOCK? ••• Page 6 Turn On (Your TV), Tune In Premieres Saturday, August 17, at 8pm on KQED 9 Ancient Mysteries A Heartwarming Shetland Revealed on New Season of Season Premiere!Secrets of the Dead Call the Midwife AUGUST 1 ON KQEDPAGE 9 XX PAGE X CONTENTS 2 3 4 5 6 22 PERKS + EVENTS NEWS + NOTES RADIO SCHEDULE RADIO SPECIALS TV LISTINGS PASSPORT AND PODCASTS Special events Highlights of What’s airing Your monthly guide What’s new and and member what’s happening when New and what’s going away benefits recommended PERKS + EVENTS Inside PBS and KQED: The Role and Future of Public Media Tuesday, August 13, 6:30 – 7:30pm The Commonwealth Club, San Francisco With much of the traditional local news space shrinking and trust in news at an all-time low, how are PBS and public media affiliates such as KQED adapting to the new media industry and political landscapes they face? PBS CEO and President Paula Kerger joins KQED President and CEO Michael Isip and President Emeritus John Boland to discuss the future of public media PERK amidst great technological, political and environmental upheaval. Use member code SpecialPBS for $10 off at kqed.org/events. What Makes a Classic Country Song? Wednesday, August 21, 7pm SFJAZZ Center, San Francisco Join KQED for a live concert and storytelling event that explores the essence and evolution of country music. KQED Senior Arts Editor Gabe Meline and the band Red Meat break down the musical elements, tall tales and true histories behind some iconic country songs and singers. -

CORRIDO NORTEÑO Y METAL PUNK. ¿Patrimonio Musical Urbano? Su Permanencia En Tijuana Y Sus Transformaciones Durante La Guerra Contra Las Drogas: 2006-2016

CORRIDO NORTEÑO Y METAL PUNK. ¿Patrimonio musical urbano? Su permanencia en Tijuana y sus transformaciones durante la guerra contra las drogas: 2006-2016. Tesis presentada por Pedro Gilberto Pacheco López. Para obtener el grado de MAESTRO EN ESTUDIOS CULTURALES Tijuana, B. C., México 2016 CONSTANCIA DE APROBACIÓN Director de Tesis: Dr. Miguel Olmos Aguilera. Aprobada por el Jurado Examinador: 1. 2. 3. Obviamente a Gilberto y a Roselia: Mi agradecimiento eterno y mayor cariño. A Tania: Porque tú sacrificio lo llevo en mi corazón. Agradecimientos: Al apoyo económico recibido por CONACYT y a El Colef por la preparación recibida. A Adán y Janet por su amistad y por al apoyo desde el inicio y hasta este último momento que cortaron la luz de mi casa. Los vamos a extrañar. A los músicos que me regalaron su tiempo, que me abrieron sus hogares, y confiaron sus recuerdos: Fernando, Rosy, Ángel, Ramón, Beto, Gerardo, Alejandro, Jorge, Alejandro, Taco y Eduardo. Eta tesis no existiría sin ustedes, los recordaré con gran afecto. Resumen. La presente tesis de investigación se inserta dentro de los debates contemporáneos sobre cultura urbana en la frontera norte de México y se resume en tres grandes premisas: la primera es que el corrido y el metal forman parte de dos estructuras musicales de larga duración y cambio lento cuya permanencia es una forma de patrimonio cultural. Para desarrollar esta premisa se elabora una reconstrucción historiográfica desde la irrupción de los géneros musicales en el siglo XIX, pasando a la apropiación por compositores tijuanenses a mediados del siglo XX, hasta llegar al testimonio de primera mano de los músicos contemporáneos. -

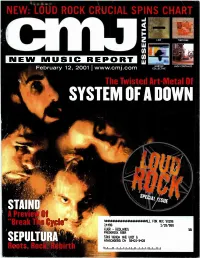

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera.