History of Scots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Place-Names in This Book Were Collected As Part of The

Introduction The place-names in this book were collected as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Board-funded (AHRB) ‘Norse-Gaelic Frontier Project, which ran from autumn 2000 to summer 2001, the full details of which will be published as Crawford and Taylor (forthcoming). Its main aim was to explore the toponymy of the drainage basin of the River Beauly, especially Strathglass,1 with a view to establishing the nature and extent of Norse place-name survival along what had been a Norse-Gaelic frontier in the 11th century. While names of Norse origin formed the ultimate focus of the Project, much wider place-name collection and analysis had to be undertaken, since it is impossible to study one stratum of the toponymy of an area without studying the totality. The following list of approximately 500 names, mostly with full analysis and early forms, many of which were collected from unpublished documents, has been printed out from the Scottish Place-Name Database, for more details of which see Appendix below. It makes no claims to being comprehensive, but it is hoped that it will serve as the basis for a more complete place-name survey of an area which has hitherto received little serious attention from place-name scholars. Parishes The parishes covered are those of Kilmorack KLO, Kiltarlity & Convinth KCV, and Kirkhill KIH (approximately 240, 185 and 80 names respectively), all in the pre-1975 county of Inverness-shire. The boundaries of Kilmorack parish, in the medieval diocese of Ross, first referred to in the medieval record as Altyre, have changed relatively little over the centuries. -

DORIC DICTIONARY Doric Is the Traditional Dialect of the North East of Scotland

DORIC DICTIONARY Doric is the traditional dialect of the North East of Scotland. It has its roots in the farming and fishing communities that made up the area. In the last 20 years it has seen a revival and is gaining more recognition and being taught at schools. The list below shows favourite Doric / Scots words or phrases with their Dictionary definition and comments underneath. Aberdeenshire Council would like to thank pupils and staff at Banff Academy, in a project with the Elphinstone Institute Aberdeen University for providing a Doric Dictionary to use on the website: http://banffmacduffheritagetrail.co.uk Auld Auld. Old. Compare with Old Scots Ald. Aye! Aye. Yes. Unknown. Bairn A child, baby, infant. Old Norse Barn. Baltic BALTIC, prop.n. Sc. printers slang usage with def. art.: a jocular term for a watercloset (Edb. 1800–74), sc. as being a chilly place, often frozen in cold weather. Black Affrontit Ashamed or deeply embarrassed, from Old French Affronter. Blether To talk foolishly or in a trivial way; to prattle, speak boastfully; a chatterbox, from Old Norse blaðra – to utter inarticulately, move the tongue to and fro. Bonnie Bonnie, Bonny, Beautiful, pretty. Late 15th century. Bonnie Bonnie, bonny, boannie. Beatiful, pretty, good, excellent, fine. Origin not known, although my 8 year old told me it was because of the French word bonne - good. Good theory. Bosie To cuddle. NE Scots, reduced form of bosom. Bourach. Whit a Bourach! A crowd, group, cluster. A disorderly heap or mess. A muddle, a mess, a state of confusion. Probably from Gaelic, búrach a mess or shambles. -

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland 15th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language (ICMRSLL) University of Glasgow, Scotland, 25-28 July 2017 Draft list of speakers and abstracts Plenary Lectures: Prof. Alessandra Petrina (Università degli Studi di Padova), ‘From the Margins’ Prof. John J. McGavin (University of Southampton), ‘“Things Indifferent”? Performativity and Calderwood’s History of the Kirk’ Plenary Debate: ‘Literary Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland: Perspectives and Patterns’ Speakers: Prof. Sally Mapstone (Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews) and Prof. Roger Mason (University of St Andrews and President of the Scottish History Society) Plenary abstracts: Prof. Alessandra Petrina: ‘From the margins’ Sixteenth-century Scottish literature suffers from the superimposition of a European periodization that sorts ill with its historical circumstances, and from the centripetal force of the neighbouring Tudor culture. Thus, in the perception of literary historians, it is often reduced to a marginal phenomenon, that draws its force solely from its powers of receptivity and imitation. Yet, as Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry, imitation can be transformed into creative appropriation: ‘the diligent imitators of Tully and Demosthenes (most worthy to be imitated) did not so much keep Nizolian paper-books of their figures and phrases, as by attentive translation (as it were) devour them whole, and made them wholly theirs’. The often lamented marginal position of Scottish early modern literature was also the key to its insatiable exploration of continental models and its development of forms that had long exhausted their vitality in Italy or France. -

The Norse Element in the Orkney Dialect Donna Heddle

The Norse element in the Orkney dialect Donna Heddle 1. Introduction The Orkney and Shetland Islands, along with Caithness on the Scottish mainland, are identified primarily in terms of their Norse cultural heritage. Linguistically, in particular, such a focus is an imperative for maintaining cultural identity in the Northern Isles. This paper will focus on placing the rise and fall of Orkney Norn in its geographical, social, and historical context and will attempt to examine the remnants of the Norn substrate in the modern dialect. Cultural affiliation and conflict is what ultimately drives most issues of identity politics in the modern world. Nowhere are these issues more overtly stated than in language politics. We cannot study language in isolation; we must look at context and acculturation. An interdisciplinary study of language in context is fundamental to the understanding of cultural identity. This politicising of language involves issues of cultural inheritance: acculturation is therefore central to our understanding of identity, its internal diversity, and the porousness or otherwise of a language or language variant‘s cultural borders with its linguistic neighbours. Although elements within Lowland Scotland postulated a Germanic origin myth for itself in the nineteenth century, Highlands and Islands Scottish cultural identity has traditionally allied itself to the Celtic origin myth. This is diametrically opposed to the cultural heritage of Scotland‘s most northerly island communities. 2. History For almost a thousand years the language of the Orkney Islands was a variant of Norse known as Norroena or Norn. The distinctive and culturally unique qualities of the Orkney dialect spoken in the islands today derive from this West Norse based sister language of Faroese, which Hansen, Jacobsen and Weyhe note also developed from Norse brought in by settlers in the ninth century and from early Icelandic (2003: 157). -

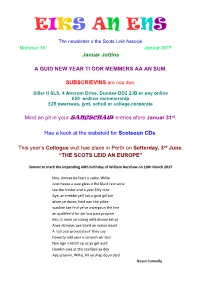

EIKS an ENS Nummer 10

EIKS AN ENS The newsletter o the Scots Leid Associe Nummer 10 Januar 2017 Januar Jottins A GUID NEW YEAR TI OOR MEMMERS AA AN SUM. SUBSCRIEVINS are nou due. Siller ti SLS, 4 Ancrum Drive, Dundee DD2 2JB or pey online £20 ordinar memmership £25 owerseas, jynt, schuil or college,corporate Mind an pit in your entries afore Januar 31st. Hae a keek at the wabsteid for Scotsoun CDs. This year’s Collogue wull hae place in Perth on Setterday, 3rd June. “THE SCOTS LEID AN EUROPE” Sonnet to mark the impending 60th birthday of William Hershaw on 19th March 2017 Nou, dinnae be feart o saxty, Willie Juist heeze a wee gless o the bluid reid wine tae the hinder end o year fifty nine Aye, an mebbe ye'll tak a guid gill tae afore ye dover, heid oan the pillae wauken tae find ye’ve owergaun the line an qualifee’d for yer bus pass propine Ken, it maks ye strang whit disnae kill ye Ance domine, aye baird an makar bauld A ‘cultural provocateur’ they say Fowerty odd year o scrievin wir leid Nae sign o lettin up as ye get auld Howkin awa at the coalface aa dey Aye screivin, Willie, till ye drap doun deid Kevin Connelly Burns’ Hamecomin When taverns stert tae stowe wi folk, Bit tae oor tale. Rab’s here as guest, An warkers thraw aff labour’s yoke, Tae handsel this by-ornar fest – As simmer days are waxin lang, Twa hunnert years an fifty’s passed An couthie chiels brak intae sang; Syne he blew in on Janwar’s blast. -

Dialectal Diversity in Contemporary Gaelic: Perceptions, Discourses and Responses Wilson Mcleod

Dialectal diversity in contemporary Gaelic: perceptions, discourses and responses Wilson McLeod 1 Introduction This essay will address some aspects of language change in contemporary Gaelic and their relationship to the simultaneous workings of language shift and language revitalisation. I focus in particular on the issue of how dialects and dialectal diversity in Gaelic are perceived, depicted and discussed in contemporary discourse. Compared to many minoritised languages, notably Irish, dialectal diversity has generally not been a matter of significant controversy in relation to Gaelic in Scotland. In part this is because Gaelic has, or at least is depicted as having, relatively little dialectal variation, in part because the language did undergo a degree of grammatical and orthographic standardisation in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with the Gaelic of the Bible serving to provide a supra-dialectal high register (e.g. Meek 1990). In recent decades, as Gaelic has achieved greater institutionalisation in Scotland, notably in the education system, issues of dialectal diversity have not been prioritised or problematised to any significant extent by policy-makers. Nevertheless, in recent years there has been some evidence of increasing concern about the issue of diversity within Gaelic, particularly as language shift has diminished the range of spoken dialects and institutionalisation in broadcasting and education has brought about a degree of levelling and convergence in the language. In this process, some commentators perceive Gaelic as losing its distinctiveness, its richness and especially its flavour or blas. These responses reflect varying ideological perspectives, sometimes implicating issues of perceived authenticity and ownership, issues which become heightened as Gaelic is acquired by increasing numbers of non-traditional speakers with no real link to any dialect area. -

Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Strasbourg, 18 September 2017 Working document Compilation of Opinions of the Advisory Committee relating to Article 10 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (4th cycle) “Article 10 1 The Parties undertake to recognise that every person belonging to a national minority has the right to use freely and without interference his or her minority language, in private and in public, orally and in writing. 2 In areas inhabited by persons belonging to national minorities traditionally or in substantial numbers, if those persons so request and where such a request corresponds to a real need, the Parties shall endeavour to ensure, as far as possible, the conditions which would make it possible to use the minority language in relations between those persons and the administrative authorities. 3 The Parties undertake to guarantee the right of every person belonging to a national minority to be informed promptly, in a language which he or she understands, of the reasons for his or her arrest, and of the nature and cause of any accusation against him or her, and to defend himself or herself in this language, if necessary with the free assistance of an interpreter.” Note: this document was produced as a working document only and does not contain footnotes. For publication purposes, please refer to the original opinions. Fourth cycle – Art 10 Table of contents 1. ARMENIA................................................................................................................................................3 -

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175Th Anniversary Honorees the Makar’S Medal

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175th Anniversary Honorees The Makar’s Medal The Chicago Scots have created a new award, the Makar’s Medal, to commemorate their 175th anniversary as the oldest nonprofit in Illinois. The Makar’s Medal will be awarded every five years to the seated Scots Makar – the poet laureate of Scotland. The inaugural recipient of the Makar’s Medal is Jackie Kay, a critically acclaimed poet, playwright and novelist. Jackie was appointed the third Scots Makar in March 2016. She is considered a poet of the people and the literary figure reframing Scottishness today. Photo by Mary McCartney Jackie was born in Edinburgh in 1961 to a Scottish mother and Nigerian father. She was adopted as a baby by a white Scottish couple, Helen and John Kay who also adopted her brother two years earlier and grew up in a suburb of Glasgow. Her memoir, Red Dust Road published in 2010 was awarded the prestigious Scottish Book of the Year, the London Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Jr. Ackerley prize. It was also one of 20 books to be selected for World Book Night in 2013. Her first collection of poetry The Adoption Papers won the Forward prize, a Saltire prize and a Scottish Arts Council prize. Another early poetry collection Fiere was shortlisted for the Costa award and her novel Trumpet won the Guardian Fiction Award and was shortlisted for the Impac award. Jackie was awarded a CBE in 2019, and made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2002. -

Norn Elements in the Shetland Dialect

Hugvísindadeild Norn elements in the Shetland dialect A Historical and Linguistic Review B.A. Essay Auður Dagný Jónsdóttir September, 2013 University of Iceland Faculty of Humanities Department of English Norn elements in the Shetland dialect A Historical and Linguistic Review B.A. Essay Auður Dagný Jónsdóttir Kt.: 270172-5129 Supervisors: Þórhallur Eyþórsson and Pétur Knútsson September, 2013 2 Abstract The languages spoken in Shetland for the last twelve hundred years have ranged from Pictish, Norn to Shetland Scots. The Norn language started to form after the settlements of the Norwegian Vikings in Shetland. When the islands came under the British Crown, Norn was no longer the official language and slowly declined. One of the main reasons the Norn vernacular lived as long as it did, must have been the distance from the mainland of Scotland. Norn was last heard as a mother tongue in the 19th century even though it generally ceased to be spoken in people’s daily life in the 18th century. Some of the elements of Norn, mainly lexis, have been preserved in the Shetland dialect today. Phonetic feature have also been preserved, for example is the consonant’s duration in the Shetland dialect closer to the Norwegian language compared to Scottish Standard English. Recent researches indicate that there is dialectal loss among young adults in Lerwick, where fifty percent of them use only part of the Shetland dialect while the rest speaks Scottish Standard English. 3 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. The origin of Norn ................................................................................................................. 6 3. The heyday of Norn ............................................................................................................... 7 4. King James III and the Reformation .................................................................................. -

AJ Aitken a History of Scots

A. J. Aitken A history of Scots (1985)1 Edited by Caroline Macafee Editor’s Introduction In his ‘Sources of the vocabulary of Older Scots’ (1954: n. 7; 2015), AJA had remarked on the distribution of Scandinavian loanwords in Scots, and deduced from this that the language had been influenced by population movements from the North of England. In his ‘History of Scots’ for the introduction to The Concise Scots Dictionary, he follows the historian Geoffrey Barrow (1980) in seeing Scots as descended primarily from the Anglo-Danish of the North of England, with only a marginal role for the Old English introduced earlier into the South-East of Scotland. AJA concludes with some suggestions for further reading: this section has been omitted, as it is now, naturally, out of date. For a much fuller and more detailed history up to 1700, incorporating much of AJA’s own work on the Older Scots period, the reader is referred to Macafee and †Aitken (2002). Two textual anthologies also offer historical treatments of the language: Görlach (2002) and, for Older Scots, Smith (2012). Corbett et al. eds. (2003) gives an accessible overview of the language, and a more detailed linguistic treatment can be found in Jones ed. (1997). How to cite this paper (adapt to the desired style): Aitken, A. J. (1985, 2015) ‘A history of Scots’, in †A. J. Aitken, ed. Caroline Macafee, ‘Collected Writings on the Scots Language’ (2015), [online] Scots Language Centre http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/A_history_of_Scots_(1985) (accessed DATE). Originally published in the Introduction, The Concise Scots Dictionary, ed.-in-chief Mairi Robinson (Aberdeen University Press, 1985, now published Edinburgh University Press), ix-xvi. -

Groves, Robert David (2005) 'Planned and Purposeful' Or 'Without Second Thought?': Formulaic Language and Incident in Barbour's Brus

Groves, Robert David (2005) 'Planned and purposeful' or 'without second thought?': formulaic language and incident in Barbour's Brus. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4469/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'Planned and Purposeful' or 'Without Second Thought'? Formulaic Language and Incident in Barbour's Brus By Robert David Groves Ph.D. Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Language and the Department of Scottish Literature Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow December 2005 (c) Robert Groves 2005 Abstract The present study investigates formulae - fixed phrases used by an oral poet in composing narrative verse - in the Older Scots poem known as the Brus, composed (probably in writing) by John Barbour, Archdeacon of Aberdeen, in the last quarter of the fourteenth century. This thesis examines the apparent discrepancy of an oral derived technique used in a sophisticated poem composed in writing by an educated and literate author. Following -

Let's Put Scotland on the Map Molly Wright

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Graduate English Association New Voices English Department Conferences Conference 2007 9-2007 Canonicity and National Identity: Let's put Scotland on the Map Molly Wright Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_conf_newvoice_2007 Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Molly, "Canonicity and National Identity: Let's put Scotland on the Map" (2007). Graduate English Association New Voices Conference 2007. Paper 9. http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_conf_newvoice_2007/9 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department Conferences at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate English Association New Voices Conference 2007 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wright, Molly University of Alabama 2007 New Voices Conference September 27-29 Graduate English Association English Department, Georgia State University Atlanta, Georgia Canonicity and National Identity: Let’s put Scotland on the Map Where is Scotland on the map of literary studies? This is a timely question for scholars to address. Recently, for example, some Scottish literature scholars have written a petition to the Modern Language Association to expand its current Scottish Literature Discussion Group into a Division on Scottish Literature at the MLA. The petition states that recent Scottish literary scholarship has “(a) recognised the wealth and distinctiveness of the Scottish literary tradition, and (b) sought to redress the anglo-centric bias of earlier treatments of Scottish writing…” (Corbett et al 1).