"Dae Scotsmen Dream O 'Lectric Leids?" Robert Crawford's Cyborg Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EIKS an ENS Nummer 10

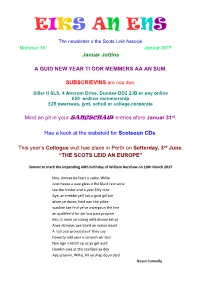

EIKS AN ENS The newsletter o the Scots Leid Associe Nummer 10 Januar 2017 Januar Jottins A GUID NEW YEAR TI OOR MEMMERS AA AN SUM. SUBSCRIEVINS are nou due. Siller ti SLS, 4 Ancrum Drive, Dundee DD2 2JB or pey online £20 ordinar memmership £25 owerseas, jynt, schuil or college,corporate Mind an pit in your entries afore Januar 31st. Hae a keek at the wabsteid for Scotsoun CDs. This year’s Collogue wull hae place in Perth on Setterday, 3rd June. “THE SCOTS LEID AN EUROPE” Sonnet to mark the impending 60th birthday of William Hershaw on 19th March 2017 Nou, dinnae be feart o saxty, Willie Juist heeze a wee gless o the bluid reid wine tae the hinder end o year fifty nine Aye, an mebbe ye'll tak a guid gill tae afore ye dover, heid oan the pillae wauken tae find ye’ve owergaun the line an qualifee’d for yer bus pass propine Ken, it maks ye strang whit disnae kill ye Ance domine, aye baird an makar bauld A ‘cultural provocateur’ they say Fowerty odd year o scrievin wir leid Nae sign o lettin up as ye get auld Howkin awa at the coalface aa dey Aye screivin, Willie, till ye drap doun deid Kevin Connelly Burns’ Hamecomin When taverns stert tae stowe wi folk, Bit tae oor tale. Rab’s here as guest, An warkers thraw aff labour’s yoke, Tae handsel this by-ornar fest – As simmer days are waxin lang, Twa hunnert years an fifty’s passed An couthie chiels brak intae sang; Syne he blew in on Janwar’s blast. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

Cultivating Identity and the Music of Ultimate Fighting

CULIVATING IDENTITY AND THE MUSIC OF ULTIMATE FIGHTING Luke R Davis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Megan Rancier, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2012 Luke R Davis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Megan Rancier, Advisor In this project, I studied the music used in Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) events and connect it to greater themes and aspects of social study. By examining the events of the UFC and how music is used, I focussed primarily on three issues that create a multi-layered understanding of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighters and the cultivation of identity. First, I examined ideas of identity formation and cultivation. Since each fighter in UFC events enters his fight to a specific, and self-chosen, musical piece, different aspects of identity including race, political views, gender ideologies, and class are outwardly projected to fans and other fighters with the choice of entrance music. This type of musical representation of identity has been discussed (although not always in relation to sports) in works by past scholars (Kun, 2005; Hamera, 2005; Garrett, 2008; Burton, 2010; Mcleod, 2011). Second, after establishing a deeper sense of socio-cultural fighter identity through entrance music, this project examined ideas of nationalism within the UFC. Although traces of nationalism fall within the purview of entrance music and identity, the UFC aids in the nationalistic representations of their fighters by utilizing different tactics of marketing and fighter branding. Lastly, this project built upon the above- mentioned issues of identity and nationality to appropriately discuss aspects of how the UFC attempts to depict fighter character to create a “good vs. -

1 Soulsister the Way to Your Heart 1988 2 Two Man Sound Disco

1 Soulsister The Way To Your Heart 1988 2 Two Man Sound Disco Samba 1986 3 Clouseau Daar Gaat Ze 1990 4 Isabelle A He Lekker Beest 1990 5 Katrina & The Waves Walking On Sunshine 1985 6 Blof & Geike Arnaert Zoutelande 2017 7 Marianne Rosenberg Ich Bin Wie Du 1976 8 Kaoma Lambada 1989 9 George Baker Selection Paloma Blanca 1975 10 Helene Fischer Atemlos Durch Die Nacht 2014 11 Mavericks Dance The Night Away 1998 12 Elton John Nikita 1985 13 Vaya Con Dios Nah Neh Nah 1990 14 Dana Winner Westenwind 1995 15 Patrick Hernandez Born To Be Alive 1979 16 Roy Orbison You Got It 1989 17 Benny Neyman Waarom Fluister Ik Je Naam Nog 1985 18 Andre Hazes Jr. Leef 2015 19 Radio's She Goes Nana 1993 20 Will Tura Hemelsblauw 1994 21 Sandra Kim J'aime La Vie 1986 22 Linda De Suza Une Fille De Tous Les Pays 1982 23 Mixed Emotions You Want Love (Maria, Maria) 1987 24 John Spencer Een Meisje Voor Altijd 1984 25 A-Ha Take On Me 1985 26 Erik Van Neygen & Sanne Veel Te Mooi 1990 27 Al Bano & Romina Power Felicita 1982 28 Queen I Want To Break Free 1984 29 Adamo Vous Permettez Monsieur 1964 30 Frans Duijts Jij Denkt Maar Dat Je Alles Mag Van Mij 2008 31 Piet Veerman Sailin' Home 1987 32 Creedence Clearwater Revival Bad Moon Rising 1969 33 Andre Hazes Ik Meen 't 1985 34 Rob De Nijs Banger Hart 1996 35 VOF De Kunst Een Kopje Koffie 1987 36 Radio's I'm Into Folk 1989 37 Corry Konings Mooi Was Die Tijd 1990 38 Will Tura Mooi, 't Leven Is Mooi 1989 39 Nick MacKenzie Hello Good Morning 1980/1996 40 Noordkaap Ik Hou Van U 1995 41 F.R. -

Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's Poetry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mendoza-Kovich, Theresa Fernandez, "Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2157. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2157 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 Approved by: Renee PrqSon, Chair, English Date Margarep Doane Cyrrchia Cotter ABSTRACT This thesis is an examination of the poetry of Edwin Morgan. It is a cultural analysis of Morgan's poetry as representation of the Scottish people. ' Morgan's poetry represents the Scottish people as determined and persistent in dealing with life's adversities while maintaining hope in a better future This hope, according to Morgan, is largely associated with the advent of technology and the more modern landscape of his native Glasgow. -

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175Th Anniversary Honorees the Makar’S Medal

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175th Anniversary Honorees The Makar’s Medal The Chicago Scots have created a new award, the Makar’s Medal, to commemorate their 175th anniversary as the oldest nonprofit in Illinois. The Makar’s Medal will be awarded every five years to the seated Scots Makar – the poet laureate of Scotland. The inaugural recipient of the Makar’s Medal is Jackie Kay, a critically acclaimed poet, playwright and novelist. Jackie was appointed the third Scots Makar in March 2016. She is considered a poet of the people and the literary figure reframing Scottishness today. Photo by Mary McCartney Jackie was born in Edinburgh in 1961 to a Scottish mother and Nigerian father. She was adopted as a baby by a white Scottish couple, Helen and John Kay who also adopted her brother two years earlier and grew up in a suburb of Glasgow. Her memoir, Red Dust Road published in 2010 was awarded the prestigious Scottish Book of the Year, the London Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Jr. Ackerley prize. It was also one of 20 books to be selected for World Book Night in 2013. Her first collection of poetry The Adoption Papers won the Forward prize, a Saltire prize and a Scottish Arts Council prize. Another early poetry collection Fiere was shortlisted for the Costa award and her novel Trumpet won the Guardian Fiction Award and was shortlisted for the Impac award. Jackie was awarded a CBE in 2019, and made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2002. -

D:\Atlantis\Artículos Para Publicar 26.1\Editado Por Ricardo Y Por Mí

ATLANTIS 26.1 (June 2004): 101–110 ISSN 0210-6124 An Interview with Liz Lochhead Carla Rodríguez González Universidad de Oviedo [email protected] An essential reference in contemporary Scottish literature, Liz Lochhead has consolidated her career as a poet, playwright and performer since she began publishing in the 1970s. Born in Motherwell, Lanarkshire, in 1947, she went to Glasgow School of Art where she started writing. After some eight years teaching art in Glasgow and Bristol, she travelled to Canada (1978) with a Scottish Writers Exchange Fellowship and became a professional writer. Memo for Spring (1971), her first collection of poems, won a Scottish Arts Council Book Award and inaugurated both a prolific career and the path many other Scottish women writers would follow afterwards. As a participant in several workshops—Stephen Mulrine’s, Philip Hobsbaum’s and Tom McGrath’s—where other contemporary writers like Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard or James Kelman also collaborated, Lochhead began to create a prestigious space of her own within a markedly masculine canon. Her works have been associated with the birth of a female voice in Scottish literature and both her texts and performances have had general success in Britain and abroad. Her plays include Blood and Ice (1982), Mary Queen of Scots Got Her Head Chopped Off (1989), Perfect Days (1998), and adaptations like Molière’s Tartuffe (1985) and Miseryguts (The Misanthrope) (2002), Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1989), Euripides’ Medea (2000), which won the 2001 Saltire Scottish Book of the Year Award, Chekhov’s Three Sisters (2000) and Euripides and Sophocles’ lives of Oedipus, Jokasta and Antigone in Thebans (2003). -

Edwin Morgan's Early Concrete Poetry

ELEANOR BELL Experimenting with the Verbivocovisual: Edwin Morgan's Early Concrete Poetry In The Order of Things: An Anthology of Scottish Sound, Pattern and Goncrete Poems, Ken Cockburn and Alec Finlay suggest that with the advent of con- crete poetry, 'Scotland connected to an international avant-garde movement in a manner barely conceivable today'. The 'classic phase' of concrete poetry in Scotiand, they note, begins around 1962, and, referencing Stephen Scobie, they point out that it should probably be regarded as an experiment in late modernism in its concerns with 'self-refiexiveness, juxtaposition and simultanism'.^ Some of the chief concerns of concrete poetry were therefore to expand upon the conceptual possibilities of poetry itself, instüling it with a new energy which could then radiate off the page, or the alternative medium on which it was presented. Both Edwin Morgan and Ian Hamilton Finlay were instantly drawn to these contrasts between the word, its verbal utterance and its overaU visual impact (or, as termed in Joyce's Finnegans Wake, its 'verbivocovisual presentements', which the Brazüian Noigandres later picked up on). Although going on to become the form's main pro- ponents within Scotiand, Morgan and Finlay recognised from early on that its Scottish reception most likely be frosty (with Hugh MacDiarmid famously asserting that 'these spatial arrangements of isolated letters and geo- metricaüy placed phrases, etc. have nothing whatever to do with poetry — any more than mud pies can be caüed architecture').^ Both poets none- theless entered into correspondence with key pioneering practitioners across the globe, and were united in their defence of the potential and legitimacy of the form. -

Jackie Kay Dates: 1978 - 1982 Role(S): Undergraduate Honorary Doctorate 2000

SURSA University of Stirling Stirling FK9 4LA SURSA [email protected] www.sursa.org.uk Interviewee: Jackie Kay Dates: 1978 - 1982 Role(s): Undergraduate Honorary doctorate 2000 Interview summary: Summary of content; with time (min:secs) 00:32 JK chose to study at Stirling because she liked the semester system; the fact that no early decision had to be taken about the degree programme and it was possible to study English with other subjects; there were courses in American poetry and novels. Compared to other universities there was freedom of choice. Stirling was close enough to her home in Glasgow and had a beautiful campus. She was only 17; she liked the sense of family provided by the University and the English Department. She took a course on the Indian novel in English and discovered that she could travel while sitting still. 02:30 She found her first year exciting; she was invited to select a poem for a tutorial and chose one about adoption by Anne Sexton. She valued the individual attention she was given; Rebecca and Russell Dobash in the Sociology Department tried to persuade her to focus on Sociology and she also studied History and Spanish but eventually took a single honours degree in English. 04:15 JK became aware of her multiple personalities and a widening of the self. She became politically active, joining the Gay Society, the Women’s Collective, Rock against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League. She formed lifelong friendships. She met other black people for almost the first time. There were 40 black students in a student population of 3000 at the University; they shared a camaraderie, acknowledging each other when they met on campus. -

Scots Verse Translation and the Second-Generation Scottish Renaissance

Sanderson, Stewart (2016) Our own language: Scots verse translation and the second-generation Scottish renaissance. PhD thesis https://theses.gla.ac.uk/7541/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Our Own Language: Scots Verse Translation and the Second-Generation Scottish Renaissance Stewart Sanderson Kepand na Sudroun bot our awyn langage Gavin Douglas, Eneados, Prologue 1.111 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction: Verse Translation and the Modern Scottish Renaissance ........................................ -

Oral Tradition

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 1 October 1986 Number 3 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley Lee Edgar Tyler Juris Dilevko Patrick Gonder Nancy Hadfield Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 14388 Columbus, Ohio 43214 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright (c) 1986 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations. -

Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 Alexander Scott

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 13 | Issue 1 Article 19 1978 Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 Alexander Scott Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Scott, Alexander (1978) "Scottish Poetry 1974-1976," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 13: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol13/iss1/19 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alexander Scott Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 For poetry in English, the major event of the period, in 1974, was the publication by Secker and Warburg, London, of the Com plete Poems of Andrew Young (1885-1971), arranged and intro duced by Leonard Clark. Although Young had lived in England since the end of the First World War, and had so identified himself with that country as to exchange his Presbyterian min istry for the Anglican priesthood in 1939, his links with Scotland where he was born (in Elgin) and educated (in Edin burg) were never broken, and he retained "the habit of mind that created Scottish philosophy, obsessed with problems of perception, with interaction between the 'I' and the 'Thou' and the 'I' and the 'It,."l Often, too, that "it" was derived from his loving observation of the Scottish landscape, to which he never tired of returning. Scarcely aware of any of this, Mr. Clark's introduction places Young in the English (or Anglo-American) tradition, in "the field company of John Clare, Robert Frost, Thomas Hardy, Edward Thomas and Edmund Blunden ••• Tennyson and Browning may have been greater influences." Such a comment overlooks one of the most distinctive qualities of Young's nature poetry, the metaphysical wit that has affinities with those seven teenth-century poets whose cast of mind was inevitably moulded by their religion.