Cultivating Identity and the Music of Ultimate Fighting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE December 8, 2016 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2016, at 10:00 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade will hold a hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” II. WITNESSES The Subcommittee will hear from the following witnesses: Randy Couture, President, Xtreme Couture; Lydia Robertson, Treasurer, Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports; Jeff Novitzky, Vice President, Athlete Health and Performance, Ultimate Fighting Championship; and Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology & Pathology, Neuropathology Core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University III. BACKGROUND A. Introduction Modern mixed martial arts (MMA) can be traced back to Greek fighting events known as pankration (meaning “all powers”), first introduced as part of the Olympic Games in the Seventh Century, B.C.1 However, pankration usually involved few rules, while modern MMA is generally governed by significant rules and regulations.2 As its name denotes, MMA owes its 1 JOSH GROSS, ALI VS.INOKI: THE FORGOTTEN FIGHT THAT INSPIRED MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND LAUNCHED SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT 18-19 (2016). 2 Jad Semaan, Ancient Greek Pankration: The Origins of MMA, Part One, BLEACHERREPORT (Jun. 9, 2009), available at http://bleacherreport.com/articles/28473-ancient-greek-pankration-the-origins-of-mma-part-one. -

Plano De Comunicação Em Mídias Sociais Para O Site MMA Brasil

Plano de Comunicação em mídias sociais para o site MMA Brasil Florianópolis Novembro de 2017 1.Introdução1 O MMA Brasil, fundado em 2008, é um site sobre esportes de luta, com maior foco no MMA. Assim como outros sites que serão citados mais a frente, ele faz parte da geração de veículos de mídia que surgiram com a popularização da internet e de sites para criação de outros sites, como o Blogspot (do Google) e Wordpress. As mídias sociais são tecnologias e práticas online usadas por pessoas ou empresas para disseminar conteúdo (RECUERO, 2009, p.102 apud SOUSA; AZEVEDO, 2010), enquanto as redes sociais são os locais onde essas pessoas ou empresas se encontram (Facebook, Twitter etc.). A primeira rede social criada foi a Classmates2 em 1995, voltada a reencontros entre colegas de colégio ou faculdade. Depois disso surgiu o Six Degrees, primeiro a apresentar o modelo de mensagens privadas e postagens em murais. Paralelo a esses sites, surgia o ICQ, plataforma para mensagens instantâneas que serviu de base para o MSN Messenger e o Skype. O ICQ não é uma rede social, mas permitia a criação de grupos de chats onde pessoas com interesses em comum podiam conversar. O MySpace, da MSN, surge em 2003 com duas opções “revolucionárias”: permitia compartilhar músicas e manter um blog. Como marketing, a empresa teve como garotos propagandas Ronaldinho Gaúcho e David Beckham, que mantinham blogs atualizados na rede. Inclusive a banda Arctic Monkeys e a cantora brasileira Mallu Magalhães ganharam fama após a divulgação de suas músicas no MySpace. No ano seguinte, duas redes sociais surgiram: Facebook e Orkut. -

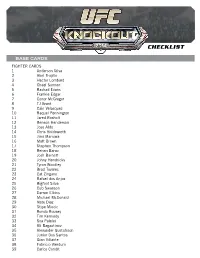

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

2005 75Th NCAA Wrestling Tournament 3/17/2005 to 3/19/2005

75th NCAA Wrestling Tournament 2005 3/17/2005 to 3/19/2005 at St. Louis Team Champion Oklahoma State - 153 Points Outstanding Wrestler: Greg Jones - West Virginia Gorriaran Award: Evan Sola - North Carolina Top Ten Team Scores Number of Individual Champs in parentheses. 1 Oklahoma State 153 (5) 6 Illinois 70.5 2 Michigan 83 (1) 7 Iowa 66 3 Oklahoma 77.5 (1) 8 Lehigh 60 4 Cornell 76.5 (1) 9 Indiana 58.5 (1) 5 Minnesota 72.5 10 Iowa State 57 Champions and Place Winners Wrestler's seed in brackets, [US] indicates unseeeded. 1251st: Joe Dubuque [5] - Indiana (2-0) 2nd: Kyle Ott [3] - Illinois 3rd: Sam Hazewinkel [1] - Oklahoma (6-3) 4th: Nick Simmons [2] - Michigan State 5th: Efren Ceballos [6] - Cal State-Bakersfield (3-2) 6th: Vic Moreno [4] - Cal Poly-SLO 7th: Bobbe Lowe [8] - Minnesota (7-3) 8th: Coleman Scott [9] - Oklahoma State 1331st: Travis Lee [1] - Cornell (6-3) 2nd: Shawn Bunch [2] - Edinboro 3rd: Tom Clum [5] - Wisconsin (2-1) 4th: Mack Reiter [3] - Minnesota 5th: Matt Sanchez [10] - Cal State-Bakersfield (10-5) 6th: Evan Sola [11] - North Carolina 7th: Mark Jayne [4] - Illinois (5-3) 8th: Drew Headlee [US] - Pittsburgh 1411st: Teyon Ware [2] - Oklahoma (3-2) 2nd: Nate Gallick [1] - Iowa State 3rd: Cory Cooperman [4] - Lehigh (10-1) 4th: Daniel Frishkorn [7] - Oklahoma State 5th: Michael Keefe [11] - Tennessee-Chattanooga (Med FFT) 6th: Andy Simmons [5] - Michigan State 7th: Casio Pero [12] - Illinois (6-5 TB1) 8th: Josh Churella [3] - Michigan 1491st: Zack Esposito [1] - Oklahoma State (5-2) 2nd: Phillip Simpson [2] - Army 3rd: -

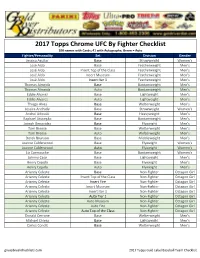

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC By Fighter Checklist 100 names with Cards; 41 with Autographs; Green = Auto Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Jessica Aguilar Base Strawweight Women's José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Top of the Class Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Museum Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Iter 1 Featherweight Men's Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Base Lightweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Auto Lightweight Men's Thiago Alves Base Welterweight Men's Jessica Andrade Base Strawweight Women's Andrei Arlovski Base Heavyweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Joseph Benavidez Base Flyweight Men's Tom Breese Base Welterweight Men's Tom Breese Auto Welterweight Men's Derek Brunson Base Middleweight Men's Joanne Calderwood Base Flyweight Women's Joanne Calderwood Auto Flyweight Women's Liz Carmouche Base Bantamweight Women's Johnny Case Base Lightweight Men's Henry Cejudo Base Flyweight Men's Henry Cejudo Auto Flyweight Men's Arianny Celeste Base Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Iter 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Tier 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Donald Cerrone Base Welterweight -

Printed in the Clovis News- Pages Past Is Compiled Journal

SATURDAY,JAN. 27, 2018 Inside: 75¢ Trump denies Times report. — Page 4B Vol. 89 ◆ No. 259 SERVING CLOVIS, PORTALES AND THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES EasternNewMexicoNews.com Courthouse evacuated ❏ A suspicious package near the law library was reported. BY THE STAFF OF THE NEWS “suspicious characteris- to determine (the pack- tics.” Agencies including age’s) origin,” Waller said. CLOVIS — Law Clovis police and firefight- Waller said a bomb threat enforcement evacuated the ers closed off the roads in called into the courthouse Curry County Courthouse one block each direction around 10:30 a.m. Friday and closed off a two-block from Seventh and Mitchell was still under investiga- perimeter near downtown streets. tion, but that threat was Clovis several hours Friday Officials with Cannon evaluated in the morning afternoon before a bomb Air Force Base’s Explosive and did not result in the squad determined a suspi- Ordnance Disposal team building’s evacuation. cious package found out- were on scene with a bomb side the Dan Buzzard Law disposal robot before 4 Officials did not immedi- Library was not an explo- p.m. and responders ately respond to questions sive device. remained after 6 p.m. to about whether Friday's Sheriff Wesley Waller conduct a secondary search incidents may have been said the package, reported of the area after evaluating connected to reports early around 2 p.m. outside the the package. this week about "telephon- building near Eighth and “We will now conduct an ic threats" that had resulted Mitchell streets, featured investigation and attempt in three arrests. Staff photo: Tony Bullocks Above: An airman with Cannon Air Force Base's Explosive Ordnance Disposal team begins work to help determine the contents of a suspicious package found near the Curry County Courthouse on Friday afternoon. -

Klipsun Magazine, 2013, Volume 43, Issue 04 - Winter

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Klipsun Magazine Western Student Publications Winter 2013 Klipsun Magazine, 2013, Volume 43, Issue 04 - Winter Branden Griffith Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/klipsun_magazine Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Griffith, anden,Br "Klipsun Magazine, 2013, Volume 43, Issue 04 - Winter" (2013). Klipsun Magazine. 153. https://cedar.wwu.edu/klipsun_magazine/153 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Klipsun Magazine by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KLIPSUNRISE | WINTER 2013 On Ice Takedowns, Strikes and Submissions Earth Rise Experiencing the ultimate thrill sport Life behind the gloves Rediscovering our home planet DEAR READER, Klipsun is an independent student publication of Western Washington University EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Branden Griffith MANAGING EDITOR Lani Farley COPY EDITOR Lisa Remy STORY EDITORS Olivia Henry Chelsea Poppe Lauren Simmons LEAD DESIGNER Julien Guay-Binion DESIGNERS Adam Bussing Kinsey Davis PHOTO EDITOR Brooke Warren Photo by Brooke Warren PHOTOGRAPHERS Brooke Warren Mindon Win ime to come clean. I’m afraid of flying. This issue of Klipsun tells the tale of the man who helped ONLINE EDITOR Unfortunately, I didn’t know this until the us discover Earth through a photo, and why owning solar Elyse Tan airplane I was on started taxiing down the panels in a state known for rain isn’t a terrible idea. runway, preparing to take me and my family to People stronger than I, the 15-year-old kid sweating WRITERS the happiest place on Earth: Disneyland. -

Are Ufc Fighters Employees Or Independent Contractors?

Conklin Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 4/27/20 8:42 PM TWO CLASSIFICATIONS ENTER, ONE CLASSIFICATION LEAVES: ARE UFC FIGHTERS EMPLOYEES OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS? MICHAEL CONKLIN* I. INTRODUCTION The fighters who compete in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (“UFC”) are currently classified as independent contractors. However, this classification appears to contradict the level of control that the UFC exerts over its fighters. This independent contractor classification severely limits the fighters’ benefits, workplace protections, and ability to unionize. Furthermore, the friendship between UFC’s brash president Dana White and President Donald Trump—who is responsible for making appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”)—has added a new twist to this issue.1 An attorney representing a former UFC fighter claimed this friendship resulted in a biased NLRB determination in their case.2 This article provides a detailed examination of the relationship between the UFC and its fighters, the relevance of worker classifications, and the case law involving workers in related fields. Finally, it performs an analysis of the proper classification of UFC fighters using the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) Twenty-Factor Test. II. UFC BACKGROUND The UFC is the world’s leading mixed martial arts (“MMA”) promotion. MMA is a one-on-one combat sport that combines elements of different martial arts such as boxing, judo, wrestling, jiu-jitsu, and karate. UFC bouts always take place in the trademarked Octagon, which is an eight-sided cage.3 The first UFC event was held in 1993 and had limited rules and limited fighter protections as compared to the modern-day events.4 UFC 15 was promoted as “deadly” and an event “where anything can happen and probably will.”6 The brutality of the early UFC events led to Senator John * Powell Endowed Professor of Business Law, Angelo State University. -

2015 Topps UFC Chronicles Checklist

BASE FIGHTER CARDS 1 Royce Gracie 2 Gracie vs Jimmerson 3 Dan Severn 4 Royce Gracie 5 Don Frye 6 Vitor Belfort 7 Dan Henderson 8 Matt Hughes 9 Andrei Arlovski 10 Jens Pulver 11 BJ Penn 12 Robbie Lawler 13 Rich Franklin 14 Nick Diaz 15 Georges St-Pierre 16 Patrick Côté 17 The Ultimate Fighter 1 18 Forrest Griffin 19 Forrest Griffin 20 Stephan Bonnar 21 Rich Franklin 22 Diego Sanchez 23 Hughes vs Trigg II 24 Nate Marquardt 25 Thiago Alves 26 Chael Sonnen 27 Keith Jardine 28 Rashad Evans 29 Rashad Evans 30 Joe Stevenson 31 Ludwig vs Goulet 32 Michael Bisping 33 Michael Bisping 34 Arianny Celeste 35 Anderson Silva 36 Martin Kampmann 37 Joe Lauzon 38 Clay Guida 39 Thales Leites 40 Mirko Cro Cop 41 Rampage Jackson 42 Frankie Edgar 43 Lyoto Machida 44 Roan Carneiro 45 St-Pierre vs Serra 46 Fabricio Werdum 47 Dennis Siver 48 Anthony Johnson 49 Cole Miller 50 Nate Diaz 51 Gray Maynard 52 Nate Diaz 53 Gray Maynard 54 Minotauro Nogueira 55 Rampage vs Henderson 56 Maurício Shogun Rua 57 Demian Maia 58 Bisping vs Evans 59 Ben Saunders 60 Soa Palelei 61 Tim Boetsch 62 Silva vs Henderson 63 Cain Velasquez 64 Shane Carwin 65 Matt Brown 66 CB Dollaway 67 Amir Sadollah 68 CB Dollaway 69 Dan Miller 70 Fitch vs Larson 71 Jim Miller 72 Baron vs Miller 73 Junior Dos Santos 74 Rafael dos Anjos 75 Ryan Bader 76 Tom Lawlor 77 Efrain Escudero 78 Ryan Bader 79 Mark Muñoz 80 Carlos Condit 81 Brian Stann 82 TJ Grant 83 Ross Pearson 84 Ross Pearson 85 Johny Hendricks 86 Todd Duffee 87 Jake Ellenberger 88 John Howard 89 Nik Lentz 90 Ben Rothwell 91 Alexander Gustafsson -

FATHOM EVENTS and UFC® BRING SOLD-OUT UFC® 180: VELASQUEZ Vs

FATHOM EVENTS AND UFC® BRING SOLD-OUT UFC® 180: VELASQUEZ vs. WERDUM TO U.S. CINEMAS LIVE FROM MEXICO CITY ON NOV. 15 DENVER, CO – UFC® returns to movie theaters nationwide on Sat., Nov. 15 at 10:00 p.m. ET / 7:00 p.m. PT, as Fathom Events and UFC bring UFC® 180: VELASQUEZ vs. WERDUM, the UFC’s first-ever event in Mexico, to the big screen. Fans will have a front-row Octagon® view of all the action when heavyweight champion Cain Velasquez collides with no.1 contender Fabricio Werdum in the five-round main event on Nov. 15. Broadcast live from the sold-out Arena Ciudad de México in Mexico City, audiences will witness the culmination of 12 weeks of rivalry and competition built up between these two heavyweight coaches on The Ultimate Fighter® Latin America, the UFC’s famed reality television series. Tickets to watch UFC® 180: VELASQUEZ vs. WERDUM on the big screen are available at participating theater box offices and at www.FathomEvents.com. The event will be presented in more than 400 select movie theaters around the country through Fathom’s Digital Broadcast Network. For a complete list of theater locations and prices, visit the Fathom Events website (theaters and participants are subject to change). “UFC 180 is a historic event and fans in theaters nationwide will be treated to the ultimate, front-row Octagon experience as Velasquez and Werdum battle for the title on the big screen,” said Dan Diamond, senior vice president of Fathom Events. UFC heavyweight champion Cain Velasquez (13-1 in his professional career, fighting out of San Jose, Calif.), an agile and explosive heavyweight with a strong wrestling base, is currently the only heavyweight titleholder of Mexican descent in combat sports around the world. -

Read a Copy of the Full Lawsuit

1 STEPHEN C. GREBING, State Bar No. 178046 [email protected] 2 IAN R. FRIEDMAN, State Bar No. 292390 3 [email protected] WINGERT GREBING BRUBAKER & JUSKIE LLP 4 One America Plaza, Suite 1200 600 West Broadway 5 San Diego, CA 92101 (619) 232-8151; Fax (619) 232-4665 6 7 Attorneys for Plaintiffs GRANT LYON and ADRIAN DI LENA 8 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 9 FOR THE COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO – CIVIC CENTER COURTHOUSE 10 GRANT LYON, by and through his Guardian Ad Case No.: 11 Litem SHELLY LYON, and ADRIAN DI LENA, by and through his Guardian Ad Litem JANE DI IMAGED FILE 12 LENA, COMPLAINT FOR: 13 Plaintiffs/Petitioners, (1) VIOLATION OF THE EQUAL 14 vs. PROTECTION CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE 15 COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO, a UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION governmental agency; DR. SUSAN PHILIP, in her AND VIOLATION OF ARTICLE 1, 16 official capacity as Acting Public Health Officer, SECTION 7 OF THE CALIFORNIA County of San Francisco; GOVERNOR GAVIN CONSTITUTION; AND 17 NEWSOM, in his official capacity as the Governor of the State of California; the (2) WRIT OF MANDAMUS (CCP §1085) 18 CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH, a department of the Dept: 19 State of California; and DOES 1 through 100, Judge: WINGERT GREBING BRUBAKER & JUSKIE LLP inclusive, 20 Action Filed: Defendants/Respondents. Trial Date: 21 22 COMES NOW Plaintiffs/Petitioners GRANT LYON and ADRIAN DI LENA and allege as 23 follows: 24 INTRODUCTION 25 In March 2020, California Governor Newsom issued a series of disaster declarations, executive 26 orders, rules, and regulations responding to an outbreak of a novel coronavirus (COVID-19) which the 27 World Health Organization (“WHO”) and the Center for Disease Control (“CDC”) declared a 28 pandemic. -

Dos Santos Has a Chance to Grow, Develop from Loss

dos Santos has a chance to grow, develop from loss Author : Robert D. Cobb Former UFC heavyweight champion Junior dos Santos learned a lot in his title fight with Cain Velasquez at UFC 155. I hope dos Santos paid attention because Velasquez put the blueprint to regaining his title right in front of him. Velasquez dominated from start to finish -- he won every round convincingly. Dos Santos learned he needs to become a better all-around fighter -- Velasquez is a better grappler, wrestler and, Saturday, was a better striker. Velasquez was able to mix up his strikes to take dos Santos down at will. The latter was the most-surprising; until this fight, dos Santos was widely-regarded as the best striker in the division. He has 10 victories by TKO or KO. Simply put, Velasquez proved himself the better fighter by showing more diversity in his game. Against most heavyweight fighters dos Santos doesn't need to be great at more than one aspect of the cage but against top-level fighters, heavy hands aren't always enough. He became champion without becoming a great wrestler -- partly because the depth of skill set at heavyweight is not as good as other divisions and partly because his striking is so dynamic. He showed that in the first fight with Velasquez, when he knocked him out early in the first round. 1 / 2 In a bout with talented submission artist Frank Mir and a separate fight with Roy Nelson, dos Santos stalked them around the ring with his fists. This time, Velasquez did the stalking.