Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 Alexander Scott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Prose Supplement 7 (2011) [Click for Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1876/prose-supplement-7-2011-click-for-pdf-31876.webp)

Prose Supplement 7 (2011) [Click for Pdf]

PS edited by Raymond Friel and Richard Price number 7 Ten Richard Price It’s ten years since I started Painted, spoken. Looking back over the issues of the magazine, two of the central patterns were there from the word go. They’re plain as day in the title: the fluid yet directing edge poetry shares with the visual arts, and, somewhere so far in the other direction it’s almost the same thing, the porous edge poetry shares with sound or performance, so porous you can hear it in its hollows. Although the magazine grew out of serial offences in little magazineship, the first impulse was to be quite different formally from Gairfish, Verse, and Southfields, each of which had placed a premium on explanation, on prose engagement, and on the analysis of the cultural traditions from which the poems they published either appeared to emerge or through which, whatever their actual origins, they could be understood. Painted, spoken would be much more tight-lipped, a gallery without the instant contextualisation demanded by an educational agenda (perhaps rightly in a public situation, but a mixed model is surely better than a constant ‘tell-us-what-to-think’ approach and the public isn’t always best served by conventional teaching). Instead, poems in Painted, spoken would take their bearings from what individual readers brought to the texts ‘themselves’ - because readers are never really alone - and also from the association of texts with each other, in a particular issue and across issues. The magazine went on its laconic way for several years until a different perspective began to open up, a crystal started to solidify, whatever metaphor you’d care to use for time-lapse comprehension (oh there’s another one): in management-speak, significant change impressed on the strategy and the strategy needed to change. -

EM Forster's Howards End and Virginia Woolfs Mrs. Dalloway

The Metropolis and the Oceanic Metaphor: E.M. Forster's Howards End and Virginia Woolfs Mrs. Dalloway Melissa Baty UH 450 / Fall 2003 Advisor: Dr. Jon Hegglund Department of English Honors Thesis ************************* PASS WITH DISTINCTION Thesis Advisor Signature Page 1 of 1 TO THE UNIVERSITY HONORS COLLEGE: As thesis advisor for Me~~'Y3 ~3 I have read this paper and find it satisfactory. 1 1-Z2.-03 Date " http://www.wsu.edu/~honors/thesis/AdvisecSignature.htm 9/22/2003 Precis Statement ofResearch Problem: In the novels Howards End by E.M. Forster and Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, the two authors illwninate their portrayal ofearly twentieth-century London and its rising modernity with oceanic metaphors. My research in history, cultural studies, literary criticism, and psychoanalytic theory aimed to discover why and to what end Forster and Woolf would choose this particular image for the metropolis itselfand for social interactions within it. Context of the Problem: My interpretation of the oceanic metaphor in the novels stems from the views of particular theorists and writers in urban psychology and sociology (Anthony Vidler, Georg Simmel, Jack London) and in psychoanalysis (Sigmund Freud, particularly in his correspondence with writer Romain Rolland). These scholars provide descriptions ofthe oceanic in varying manners, yet reflect the overall trend in the period to characterizing life experience, and particularly experiences in the city, through images and metaphors ofthe sea. Methods and Procedures: The research for this project entailed reading a wide range ofhistorically-specific background regatg ¥9fSter, W661f~ eity of I .Q~e various academic areas listed above in order to frame my conclusions about the novels appropriately. -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

Off the Pedestal, on the Stage: Animation and De-Animation in Art

Off the Pedestal; On the Stage Animation and De-animation in Art and Theatre Aura Satz Slade School of Fine Art, University College, London PhD in Fine Art 2002 Abstract Whereas most genealogies of the puppet invariably conclude with robots and androids, this dissertation explores an alternative narrative. Here the inanimate object, first perceived either miraculously or idolatrously to come to life, is then observed as something that the live actor can aspire to, not necessarily the end-result of an ever evolving technological accomplishment. This research project examines a fundamental oscillation between the perception of inanimate images as coming alive, and the converse experience of human actors becoming inanimate images, whilst interrogating how this might articulate, substantiate or defy belief. Chapters i and 2 consider the literary documentation of objects miraculously coming to life, informed by the theology of incarnation and resurrection in Early Christianity, Byzantium and the Middle Ages. This includes examinations of icons, relics, incorrupt cadavers, and articulated crucifixes. Their use in ritual gradually leads on to the birth of a Christian theatre, its use of inanimate figures intermingling with live actors, and the practice of tableaux vivants, live human figures emulating the stillness of a statue. The remaining chapters focus on cultural phenomena that internalise the inanimate object’s immobility or strange movement quality. Chapter 3 studies secular tableaux vivants from the late eighteenth century onwards. Chapter 4 explores puppets-automata, with particular emphasis on Kempelen's Chess-player and the physical relation between object-manipulator and manipulated-object. The main emphasis is a choreographic one, on the ways in which live movement can translate into inanimate hardness, and how this form of movement can then be appropriated. -

Angeletti, Gioia (1997) Scottish Eccentrics: the Tradition of Otherness in Scottish Poetry from Hogg to Macdiarmid

Angeletti, Gioia (1997) Scottish eccentrics: the tradition of otherness in Scottish poetry from Hogg to MacDiarmid. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2552/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] SCOTTISH ECCENTRICS: THE TRADITION OF OTHERNESS IN SCOTTISH POETRY FROM HOGG TO MACDIARMID by Gioia Angeletti 2 VOLUMES VOLUME I Thesis submitted for the degreeof PhD Department of Scottish Literature Facultyof Arts, Universityof Glasgow,October 1997 ý'i ý'"'ý# '; iý "ý ý'; ý y' ý': ' i ý., ý, Fý ABSTRACT This study attempts to modify the received opinion that Scottish poetry of the nineteenth-centuryfailed to build on the achievementsof the century (and centuries) before. Rather it suggeststhat a number of significant poets emerged in the period who represent an ongoing clearly Scottish tradition, characterised by protean identities and eccentricity, which leads on to MacDiarmid and the `Scottish Renaissance'of the twentieth century. The work of the poets in question is thus seen as marked by recurring linguistic, stylistic and thematic eccentricities which are often radical and subversive. -

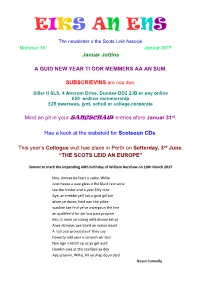

EIKS an ENS Nummer 10

EIKS AN ENS The newsletter o the Scots Leid Associe Nummer 10 Januar 2017 Januar Jottins A GUID NEW YEAR TI OOR MEMMERS AA AN SUM. SUBSCRIEVINS are nou due. Siller ti SLS, 4 Ancrum Drive, Dundee DD2 2JB or pey online £20 ordinar memmership £25 owerseas, jynt, schuil or college,corporate Mind an pit in your entries afore Januar 31st. Hae a keek at the wabsteid for Scotsoun CDs. This year’s Collogue wull hae place in Perth on Setterday, 3rd June. “THE SCOTS LEID AN EUROPE” Sonnet to mark the impending 60th birthday of William Hershaw on 19th March 2017 Nou, dinnae be feart o saxty, Willie Juist heeze a wee gless o the bluid reid wine tae the hinder end o year fifty nine Aye, an mebbe ye'll tak a guid gill tae afore ye dover, heid oan the pillae wauken tae find ye’ve owergaun the line an qualifee’d for yer bus pass propine Ken, it maks ye strang whit disnae kill ye Ance domine, aye baird an makar bauld A ‘cultural provocateur’ they say Fowerty odd year o scrievin wir leid Nae sign o lettin up as ye get auld Howkin awa at the coalface aa dey Aye screivin, Willie, till ye drap doun deid Kevin Connelly Burns’ Hamecomin When taverns stert tae stowe wi folk, Bit tae oor tale. Rab’s here as guest, An warkers thraw aff labour’s yoke, Tae handsel this by-ornar fest – As simmer days are waxin lang, Twa hunnert years an fifty’s passed An couthie chiels brak intae sang; Syne he blew in on Janwar’s blast. -

Tom Leonard (1944 -2018) — 'Notes Personal' in Response to His Life

Tom Leonard (1944 -2018) — ‘Notes Personal’ in Response to his Life and Work an essay by Jim Ferguson 1. How I met the human being named ‘Tom Leonard’ I was ill with epilepsy and post-traumatic stress disorder. It was early in 1986. I was living in a flat on Causeyside Street, Paisley, with my then partner. We were both in our mid-twenties and our relationship was happy and loving. We were rather bookish with quite a strong sense of Scottish and Irish working class identity and an interest in socialism, social justice. I think we both held the certainty that the world could be changed for the better in myriad ways, I know I did and I think my partner did too. You feel as if you share these basic things, a similar basic outlook, and this is probably why you want to live in a little tenement flat with one human being rather than any other. We were not career minded and our interest in money only stretched so far as having enough to live on and make ends meet. Due to my ill health I wasn’t getting out much and rarely ventured far from the flat, though I was working on ‘getting better’. In these circumstances I found myself filling my afternoons writing stories and poems. I had a little manual portable typewriter and would sit at a table and type away. I was a very poor typist which made poetry much more appealing and enjoyable because it could be done in fewer words with a lot less tipp-ex. -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's Poetry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mendoza-Kovich, Theresa Fernandez, "Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2157. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2157 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 Approved by: Renee PrqSon, Chair, English Date Margarep Doane Cyrrchia Cotter ABSTRACT This thesis is an examination of the poetry of Edwin Morgan. It is a cultural analysis of Morgan's poetry as representation of the Scottish people. ' Morgan's poetry represents the Scottish people as determined and persistent in dealing with life's adversities while maintaining hope in a better future This hope, according to Morgan, is largely associated with the advent of technology and the more modern landscape of his native Glasgow. -

Brown, George Mackay (1921–1996)

George Mackay Brown in Facts on File Companion to British Poetry 1900 to the Present BROWN, GEORGE MACKAY (1921–1996) To understand George Mackay Brown’s art, the reader must appreciate its deep rootedness in the poet’s place of birth. Orkney looms large in all of his writings, its lore, language, history, and myth, providing Brown with most of the material he used in his 50 years as a professional writer. Brown was born and lived all his life in Stromness, a small town on Mainland, the larg- est of the Orkney Islands, situated off the northern coast of Scotland. Except for his student years at New- battle Abbey and Edinburgh University, as a protégé of EDWIN MUIR, Brown rarely left Orkney. He returned time and again to the matter of Orkney as inspiration for his work, often evoking its Viking heritage and the influence of the mysterious Neolithic settlers who pre- dated the Norsemen. The other abiding influence on his work is his Roman Catholicism—he converted at the age of 40, after years of reflection. Brown’s background was poor. His father, John Brown, was a postman, and his mother, Mhairi Mackay Brown, worked in a hotel. Brown attended the local school, Stromness Academy, where he discovered his talent for writing in the weekly “compositions” set by his English teacher. A bout of tuberculosis ended his schooling and led to his becoming a writer, since he was scarcely fit for a regular job. From the early 1940s, he earned a living as a professional writer, often publishing his work in the local newspaper, for which he continued to write until a week before his death. -

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175Th Anniversary Honorees the Makar’S Medal

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175th Anniversary Honorees The Makar’s Medal The Chicago Scots have created a new award, the Makar’s Medal, to commemorate their 175th anniversary as the oldest nonprofit in Illinois. The Makar’s Medal will be awarded every five years to the seated Scots Makar – the poet laureate of Scotland. The inaugural recipient of the Makar’s Medal is Jackie Kay, a critically acclaimed poet, playwright and novelist. Jackie was appointed the third Scots Makar in March 2016. She is considered a poet of the people and the literary figure reframing Scottishness today. Photo by Mary McCartney Jackie was born in Edinburgh in 1961 to a Scottish mother and Nigerian father. She was adopted as a baby by a white Scottish couple, Helen and John Kay who also adopted her brother two years earlier and grew up in a suburb of Glasgow. Her memoir, Red Dust Road published in 2010 was awarded the prestigious Scottish Book of the Year, the London Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Jr. Ackerley prize. It was also one of 20 books to be selected for World Book Night in 2013. Her first collection of poetry The Adoption Papers won the Forward prize, a Saltire prize and a Scottish Arts Council prize. Another early poetry collection Fiere was shortlisted for the Costa award and her novel Trumpet won the Guardian Fiction Award and was shortlisted for the Impac award. Jackie was awarded a CBE in 2019, and made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2002.