Am Ha-Aretz in the Mishnah1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congregation Torah Ohr 19146 Lyons Road, Boca Raton, FL 33434 (561) 479-4049 ● ● [email protected] Rabbi Benjamin S

February 5 — 11, 2021 23 — 29 Shevat 5781 Congregation Torah Ohr 19146 Lyons Road, Boca Raton, FL 33434 (561) 479-4049 ● www.torahohrboca.org ● [email protected] Rabbi Benjamin S. Yasgur President, Jonas Waizer Office Hours Monday - Thursday 9:00am - 3:00pm, Friday 9:00am - 12noon WEEKDAY TIMES Earliest Davening (Fri-Thurs) 5:53am* Mishna Yomit (in Shul & online) 15 min. before Mincha Earliest Tallit/Tefillin (Fri-Thurs) 6:20am* Mincha/Ma’ariv (Shul & Tent) (S-Th) Shacharit at Shul (starting with Pesukai D’Zimra) 7:30am Shacharit in the Tent (starting with Pesukai D’Zimra) 8:30am Daven Mincha (S-Th) prior to 6:08pm Daf Yomi (online) 8:30am Repeat Kriat Shema after 6:46pm* Chumash Class (online) 9:30am *These are the latest times during the week BS”D CONGREGATION TORAH OHR NEW - UPDATED POLICIES FOR KEEPING OUR COMMUNITY SAFE We enjoy the seasonal return of our cherished congregants, friends, and neighbors. At the same time, let us acknowledge that the Corona-19 pandemic is not yet over. We cannot afford complacency in our sheltered senior community until the pandemic is fully controlled. Considering the situation of pikuach nefesh, the Shul will continue policies that protect all our members. We want you in Shul ASAP. But first, individuals returning to Florida, even from short out-of-state stays, must adhere to the CDC, Florida State and Shul rules: a) Self-isolate for 12 days; DO NOT ATTEND SHUL, including outdoor minyanim. If you have no symptoms after 12 days, please SHABBAT YITRO register to attend shul minyanim. -

Foreword, Abbreviations, Glossary

FOREWORD, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY The Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES Reformatted by Reuven Brauner, Raanana 5771 1 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY Halakhah.com Presents the Contents of the Soncino Babylonian Talmud TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES, GLOSSARY AND INDICES UNDER THE EDITORSHIP OF R AB B I D R . I. EPSTEIN B.A., Ph.D., D. Lit. FOREWORD BY THE VERY REV. THE LATE CHIEF RABBI DR. J. H. HERTZ INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITOR THE SONCINO PRESS LONDON Original footnotes renumbered. 2 FOREWORDS, ABBREVIATIONS, GLOSSARY These are the Sedarim ("orders", or major There are about 12,800 printed pages in the divisions) and tractates (books) of the Soncino Talmud, not counting introductions, Babylonian Talmud, as translated and indexes, glossaries, etc. Of these, this site has organized for publication by the Soncino about 8050 pages on line, comprising about Press in 1935 - 1948. 1460 files — about 63% of the Soncino Talmud. This should in no way be considered The English terms in italics are taken from a substitute for the printed edition, with the the Introductions in the respective Soncino complete text, fully cross-referenced volumes. A summary of the contents of each footnotes, a master index, an index for each Tractate is given in the Introduction to the tractate, scriptural index, rabbinical index, Seder, and a detailed summary by chapter is and so on. given in the Introduction to the Tractate. SEDER ZERA‘IM (Seeds : 11 tractates) Introduction to Seder Zera‘im — Rabbi Dr. I Epstein INDEX Foreword — The Very Rev. The Chief Rabbi Israel Brodie Abbreviations Glossary 1. -

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Chapter Fourteen Rabbinic and Other Judaisms, from 70 to Ca

Chapter Fourteen Rabbinic and Other Judaisms, from 70 to ca. 250 The war of 66-70 was as much a turning point for Judaism as it was for Christianity. In the aftermath of the war and the destruction of the Jerusalem temple Judaeans went in several religious directions. In the long run, the most significant by far was the movement toward rabbinic Judaism, on which the source-material is vast but narrow and of dubious reliability. Other than the Mishnah, Tosefta and three midrashim, almost all rabbinic sources were written no earlier than the fifth century (and many of them much later), long after the events discussed in this chapter. Our information on non-rabbinic Judaism in the centuries immediately following the destruction of the temple is scanty: here we must depend especially on archaeology, because textual traditions are almost totally lacking. This is especially regrettable when we recognize that two non-rabbinic traditions of Judaism were very widespread at the time. Through at least the fourth century the Hellenistic Diaspora and the non-rabbinic Aramaic Diaspora each seem to have included several million Judaeans. Also of interest, although they were a tiny community, are Jewish Gnostics of the late first and second centuries. The end of the Jerusalem temple meant also the end of the Sadducees, for whom the worship of Adonai had been limited to sacrifices at the temple. The great crowds of pilgrims who traditionally came to the city for the feasts of Passover, Weeks and Tabernacles were no longer to be seen, and the temple tax from the Diaspora that had previously poured into Jerusalem was now diverted to the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus in Rome. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

THE HANDBOOK of PALESTINE MACMILLAN and CO., Limited

VxV'*’ , OCT 16 1923 i \ A / <$06JCAL Division DSI07 S; ct Ion .3.LB Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Princeton Theological Seminary Library https://archive.org/details/handbookofpalestOOIuke THE HANDBOOK OF PALESTINE MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA • MADRAS MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO DALLAS • SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd TORONTO DOME OF THE ROCK AND DOME OF THE CHAIN, JERUSALEM. From a Drawing by Benton Fletcher. THE HANDBOOK OF P A L E ST IN #F p“% / OCT 16 1923 V\ \ A A EDITED' BY V HARRY CHARLES LUKE, B.Litt., M.A. ASSISTANT GOVERNOR OF JERUSALEM AND ^ EDWARD KEITH-ROACH ASSISTANT CHIEF SECRETARY TO THE GOVERNMENT OF PALESTINE WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY The Right Hon. SIR HERBERT SAMUEL, P.C., G.B.E. HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR PALESTINE Issued under the Authority of the Government of Palestine MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON 1922 COPYRIGHT PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN PREFACE The Handbook of Palestine has been written and printed during a period of transition in the administration of the country. While the book was in the press the Council of the League of Nations formally approved the conferment on Great Britain of the Mandate for Palestine; and, consequent upon this act, a new constitution is to come into force, the nominated Advisory Council will be succeeded by a partly elected Legislative Council, and other changes in the direction of greater self-government, which had awaited the ratification of the Mandate, are becoming operative. Again, on the ist July, 1922, the adminis¬ trative divisions of the country were reorganized. -

Organization of the Talmud

Organization of the Talmud Contents The Sections and Tracts of the Talmud ................................. 2 Seder Zeraim (Seeds) ............................................ 2 Seder Moed (Festivals) ........................................... 2 Seder Nashim (Women) .......................................... 2 Seder Nezikin (Damages) ......................................... 3 Seder Kodashim (Holy Things) ...................................... 3 Seder Toharot (Purity) ........................................... 3 The rabbis of the 2nd and 3rd centuries after Christ At a certain point, probably during the 2nd cen- organized the Talmud in the form we find it to- tury after Christ, the Pharisees gave permission for day. Rabbi Jehudah the Nasi (3rd Century, presi- writing the law. Until then it was absolutely forbid- dent of the Sanhedrin) began the work of gathering den to put the oral law in writing. No sooner had together all the notes, archives, and records from this been granted that the number of manuscripts which the Talmud would be compiled. The scholars began to be very great, and when Rabbi Jehudah in Spain asserted that these notes had been in ex- had been confirmed in authority (since he enjoyed istence since schools had begun in Israel, possibly the friendship of a Roman named Antonius, who from as early as Ezra’s time. was in power in Rome), he discovered that “from the multitude of the trees the forest could not be Other Jewish scholars of that period, notably those seen.” living in France, declared that not a line was writ- ten down anywhere until this compilation began, The period of the 3rd century was very favorable for and that the writing was done from memory alone, this undertaking, because the Talmud, and its Jew- the memory of the living rabbis who were the con- ish followers, enjoyed a rest from persecutors. -

Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot

The Child at the Edge of the Cemetery: Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot MARTIN S. COHEN j i f the Mishnah wears seven veils so as modestly to hide its inmost charms from all but the most worthy of its admirers, then its sixth sec- I tion, Seder Tohorot, wears seventy of them. But to merit a peek behind those many veils requires more than the ardor or determination of even the most persistent suitor. Indeed, there is no more daunting section of the rab- binic corpus to understand—or more challenging to enjoy or more formidable to analyze . or more demoralizing to the student whose a pri- ori assumption is that the texts of classical Judaism were meant, above all, to inspire spiritual growth through their devotional study. It is no coincidence that it is rarely, if ever, studied in much depth. Indeed, other than for Tractate Niddah (which deals mostly with the laws concerning the purity status of menstruant women and the men who come into casual or intimate contact with them), there is no Talmud for any trac- tate in the seder, which detail can be interpreted to suggest that even the amoraim themselves found the material more than just slightly daunting.1 Cast in the language of science, yet clearly not founded on the kind of scien- tific principles “real” scientists bring to the informed inspection and analysis of the physical universe, the laws put forward in the sixth seder of the Mish- nah appear—at least at first blush—to have a certain dreamy arbitrariness about them able to make even the most assiduous reader despair of finding much fodder for contemplative analysis. -

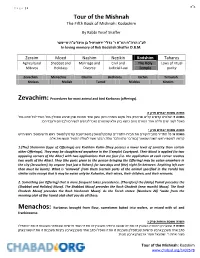

Tour of the Mishnah the Fifth Book of Mishnah: Kodashim

ב"ה P a g e | 1 Tour of the Mishnah The Fifth Book of Mishnah: Kodashim By Rabbi Yosef Shaffer לע"נ הרה"ח הוו"ח ר' גדלי' ירחמיא-ל בן מיכל ע"ה שייפער In loving memory of Reb Gedaliah Shaffer O.B.M. Zeraim Moed Nashim Nezikin Kodshim Taharos Agricultural Shabbat and Marriage and Civil and The Holy Laws of ritual Mitzvos Holidays Divorce Judicial Law Temple purity Zevachim Menachos Chullin Bechoros Erchin Temurah Kreisos Meilah Tamid Middos Kinnim Zevachim: Procedures for most animal and bird Korbanos (offerings). משנה מסכת זבחים פרק ה משנה ז: שלמים קדשים קלים שחיטתן בכל מקום בעזרה ודמן טעון שתי מתנות שהן ארבע ונאכלין בכל העיר לכל אדם בכל מאכל לשני ימים ולילה אחד המורם מהם כיוצא בהן אלא שהמורם נאכל לכהנים לנשיהם ולבניהם ולעבדיהם: משנה מסכת זבחים פרק י משנה א: כל התדיר מחבירו קודם את חבירו התמידים קודמין למוספין מוספי שבת קודמין למוספי ראש חדש מוספי ראש חדש קודמין למוספי ראש השנה שנאמר )במדבר כח( מלבד עולת הבקר אשר לעולת התמיד תעשו את אלה: 1.(The) Shelamim (type of Offerings) are Kodshim Kalim (they possess a lower level of sanctity than certain other Offerings). They may be slaughtered anywhere in the (Temple) Courtyard. Their blood is applied (to two opposing corners of the Altar) with two applications that are four (i.e. the application at each corner reaches two walls of the Altar). They (the parts given to the person bringing the Offering) may be eaten anywhere in the city (Jerusalem), by anyone (not just a Kohen), for two days and (the) night (in between. -

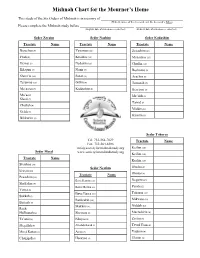

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Judges) “In All Your Gates” That They Are to Judge the People with Righteous Judgment

בייה PORTION DATE HEB DATE TORAH NEVIIM RENEWED Shoftim 18 Aug. 2018 7 Elul 5778 Deut. 16:18-21:9 Isa. 51:12-52:12 John 14:9-20 This week’s Torah portion starts with the qualification of shoftim (judges) “in all your gates” that they are to judge the people with righteous judgment. The Torah then describes how they are to judge against the accused. The Midrash questions the eligibility of judges. The immediate family of litigants are disqualified to judge as well as they are ineligible to testify as said, “The ahvot (fathers) shall not be put to death for the children, neither shall the children be put to death for the ahvot.” (Deut. 24:16) The Gemara interprets: fathers shall not be executed because of the testimony of sons, and vice versa.1 Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel (10 BCE-70 CE) said: Do not make light of justice, for it is one of the three legs of the world: justice, truth, and on peace. Therefore, we are to be mindful of not perverting justice as “you can cause the world to shake2 for it (justice) is one of the legs of Hashem’s Throne of Glory. “Righteousness and justice are the foundation of Your throne.” (Psa 85:15) The Proverbs 6:6-8 says, “Go to the ant, you lazy one; consider her halachot, and be wise: They have no guide, overseer, or ruler, yet she; Provides her food in the and gathers her food in the harvest.” The sages teach the ants has three stories in its home. -

SYNOPSIS the Mishnah and Tosefta Are Two Related Works of Legal

SYNOPSIS The Mishnah and Tosefta are two related works of legal discourse produced by Jewish sages in Late Roman Palestine. In these works, sages also appear as primary shapers of Jewish law. They are portrayed not only as individuals but also as “the SAGES,” a literary construct that is fleshed out in the context of numerous face-to-face legal disputes with individual sages. Although the historical accuracy of this portrait cannot be verified, it reveals the perceptions or wishes of the Mishnah’s and Tosefta’s redactors about the functioning of authority in the circles. An initial analysis of fourteen parallel Mishnah/Tosefta passages reveals that the authority of the Mishnah’s SAGES is unquestioned while the Tosefta’s SAGES are willing at times to engage in rational argumentation. In one passage, the Tosefta’s SAGES are shown to have ruled hastily and incorrectly on certain legal issues. A broader survey reveals that the Mishnah also contains a modest number of disputes in which the apparently sui generis authority of the SAGES is compromised by their participation in rational argumentation or by literary devices that reveal an occasional weakness of judgment. Since the SAGES are occasionally in error, they are not portrayed in entirely ideal terms. The Tosefta’s literary construct of the SAGES differs in one important respect from the Mishnah’s. In twenty-one passages, the Tosefta describes a later sage reviewing early disputes. Ten of these reviews involve the SAGES. In each of these, the later sage subjects the dispute to further analysis that accords the SAGES’ opinion no more a priori weight than the opinion of individual sages.