Global Roundtable Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Mmessage

November 2002 Inside this Issue ❖ Creative Intelligence Cheat Sheet ❖ Editor’s Corner ❖ New Members ❖ November General Meeting ❖ President’s Message President’s Message ❖ PSMA Luncheon Summary- October 2002 n an unbearably hot day in August I received a call from a former colleague. Could I possibly assist her former secretary in her job search? She likes to work the midnight O ❖ Some Tips On Enhancing shift. I've had difficulty recruiting for this particular role in the past. Someone in TLOMA must have a need. I recall my recent career move and the people who were generous with Credibility their time and encouragement. You can't always pay back, but you can pay-it-forward. So, I take out the TLOMA list looking for contact information. I must respect the privacy of ❖ TLOMA Conference TLOMA members so I can't give out any information, but I can make a couple of calls. Debt paid. Schedule of Events Next, I open my first, post September 11th commercial insurance renewal and gasp at the premium increase. I study the four-page explanation, which amounts to a recom- mendation to increase future budgets because higher costs are here to stay. It occurs to November 27 - HR SIG me that someone from the insurance industry might be a good speaker for TLOMA in December 6 - Social the coming year. December 9 – Technology SIG Now I'm moving on to my projects, with my first being the firm brochure. More phone calls and emails to collect a few samples to see what the recent styles and trends are. -

Our Path to Sustainability 2010 Review T His Might Be Our First Review but It Is Not the Start of Our Path to Sustainability

our path to SuStaINaBIlIty 2010 Review t his might be our first review but it is not the start of our path to sustainability ABOUT THIS REvIEw 06 Sourcing more sustainably This is Mars Drinks’ first sustainability review. it describes our approach and performance in managing our social, economic and environmental impacts and covers all our operations worldwide. we describe our performance throughout our value chain: how we source our ingredients; the design, manufacture, use and disposal of our products 12 r educing and packaging; and how we encourage our our operational Associates to get involved. impacts we do not discuss the impact of our drinks on health and nutrition or the experience of working at Mars, as this information is available in the Mars, incorporated Principles in Action Summary, available at www.mars.com. 16 Developing responsible Because this is our first review, we have products included additional information about our company and its history, to introduce ourselves and provide some background to the way we do business. The data provided includes all Mars Drinks operations for the 2010 calendar year, unless 20 Supporting otherwise stated. environmental data from our customers our factories is accurately recorded, and we estimate the data for our offices. in addition, some case studies and examples include information from 2009 and 2011, to better illustrate our approach. 22 Engaging our in 2011, we changed the way we measure our associates performance in some areas. we are unable to report 2010 data against these new measures, as we were not recording the required information at the time. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 OR 15(d) of The Securities Exchange Act Of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported) April 9, 2014 THE PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Ohio 1-434 31 -0411980 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission File (IRS Employer of incorporation) Number) Identification Number) One Procter & Gamble Plaza, Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 (Address of principal executive offices) Zip Code (513) 983 -1100 45202 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Zip Code Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) ITEM 7.01 REGULATION FD DISCLOSURE On April 9, 2014, The Procter & Gamble Company (“Company”) and Mars, Incorporated (“Mars”) issued a news release announcing that the companies have reached an agreement for the sale of a significant portion of the Company’s pet food business to Mars. The Company is furnishing this 8-K pursuant to Item 7.01, "Regulation FD Disclosure." SIGNATURE Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the Registrant has duly caused this Report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned hereunto duly authorized. THE PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY BY: /s/ Susan S. -

For Immediate Release Contacts: Sumitomo Corporation Expands

For Immediate Release Contacts: Ms. Jewelle Yamada Phone: 212-207-0574 E-mail: [email protected] Ms. Vanessa Goldschneider Phone: 212-207-0567 E-mail: [email protected] Sumitomo Corporation Expands Renewable Energy Portoflio as Sole Owner of Mesquite Creek Wind Farm in Texas Exclusive Long Term Agreement with Mars Inc. to Purchase Renewable Energy from Wind Farm New York, New York – April 30, 2014 – Sumitomo Corporation of Americas (SCOA) and Sumitomo Corporation (SC) (collectively Sumitomo) have acquired the remaining shares of the Mesquite Creek Wind Farm in Western Texas from co-developer BNB Renewable Energy (BNB) to achieve 100% ownership of the project. Sumitomo also announced that they have entered into a long-term agreement with Mars Inc. to purchase the renewable energy from the wind farm which will allow Mars to be effectively carbon neutral in their electricity consumption for 20+ years. Sumitomo secured financing for the project through funding from a syndicate of banks including, Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation and Mizuho Bank. “We are pleased to be partnered with Mars to help them reduce their carbon footprint and allow them to be carbon-neutral in the U.S. Mesquite Creek is a landmark project for Sumitomo and further stregthens our commitment to renewable energy and the U.S. market.”, said William Cannon, Vice President, Sumitomo Corporation of Americas. BNB, the originating developer of the project, entered into a joint venture with Sumitomo in August 2013 and they have since worked together to bring the 25,000 acre wind farm project to fruition. -

AMERICAN Li SQURRE DFINC FEBRUARY 1982 .14Impuml

p Single Copy $1.00 AMERICAN li SQURRE DFINC FEBRUARY 1982 .14impuml, Hearty Dance Darlings 23rd • New England PC • C.4,41a0.110. Square & Round Dance CONVENTION LA. 4, 1 Vow., 5.0. 51101- Wo.ceilm MA 01802 August 9, 1981 Clinton instrument wmpany Old Boston Post Hood Clinton, CT 06413 peer Sirs, It i. a plaaaure to report to you on the quality of sound that was provided to this 23rd Now England Square and Bound Dance Convention. Twelve of the halls, including Worcester Auditorium, utilised Clinton equipment set up by Jim Harris. The efficiency of this equipment con- tributed substantially to the success of the progras. Cn behalf of the convention, both committee and dancers, I'd like to thank you for your generosity in providing systems for our use. Squarely yours, , 1 Garrett Mitchell Jr. General Chairman "A Barret Of Fun In '81" It in ASD (Credit BUffliCA) Say you saw CLINTON INSTRUMENT COMPANY, PO BOX 505, CLINTON CT 06413 Tel: 203-669-7548 2 AMERICAN 0 SQURRE ORNCE VOLUME 37, No. 2 THE NATIONAL MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1982 WITH THE SWINGING LINES LEADERSHIP TIPS 13 Symposium: Social Aspects ASD FEATURES FOR ALL 17 Roberts Rules of Order 4 Co-Editorial 5 By-Line ROUNDS 7 Meanderings 20 Roundalab Report 11 What's It Like to Be Color Blind? 43 Facing the LOD 15 Positive Position on Competition 65 Flip Side— Round 21 Family Affair 65 Choreography Ratings 23 Dancing in East Germany 75 R/D Pulse Poll 25 Dandy Idea 27 Hemline 29 Encore 31 Best Club Trick SQUARE DANCE SCENE 38 Dancing Tips 19 State Line 44 Valentine Verse 35 31st National Convention 5/ Sketchpad Commentary 37 LEGACY 58 People in the News 46 Challenge Chatter 85 Book Nook 60 International News 86 Finish Line 73 Dateline 88 DoCiDo Dolores FOR CALLERS 39 Calling Tips OUR READERS SPEAK 40 Easy Level Page 50 Creative Choreography 6 Grand Zip 56 PS/MS 34 Straight Talk 64 Steal A Peek 65 Feedback Flip Side— Squares S/D Pulse Poll ‹) Underlining Note Services - --0111."‘---a. -

Your Reading: a Booklist for Junior High and Middle School Students

ED 337 804 CS 213 064 AUTHOR Nilsen, Aileen Pace, Ed. TITLE Your Reading: A Booklist for JuniOr High and Middle School Students. Eighth Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5940-0; ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 347p.y Prepared by the Committee on the Junior High and Middle School Booklist. For the previous edition, see ED 299 570. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 59400-0015; $12.95 members, $16.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Boots; Junior High Schools; Junior High School Students; *Literature Appreciation; Middle Schools; Reading Interests; Reuding Material Selection; Recreational Reading; Student Interests; *Supplementary Reading Materials IDENTIFIERS Middle School Students ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography for junior high and middle school students describes nearly 1,200 recent books to read for pleasure, for school assignments, or to satisfy curiosity. Books included are divided inco six Lajor sections (the first three contain mostly fiction and biographies): Connections, Understandings, Imaginings, Contemporary Poetry and Short Stories, Books to Help with Schoolwork, and Books Just for You. These major sections have been further subdivided into chapters; e.g. (1) Connecting with Ourselves: Accomplishments and Growing Up; (2) Connecting with Families: Close Relationships; (3) -

Engagement + Service = out Reach

MSU FOUNDATION ENGAGEMENT + SERVICE = OUTREACH ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 MSU is an AA/EEO university. AA/EEO MSU is an MSU Foundation • Post Office Box 6149 • Mississippi State, MS 39762 • 662.325.7000 • www.msufoundation.com • • 662.325.7000 MS 39762 State, Mississippi 6149 • Box Office • Post MSU Foundation Mississippi State University Foundation ENGAGEMENT + SERVICE = Outreach Annual Report 2014-2015 : 1 The people forming our Infinite Impact logo represent the more than 20,000 MSU students, who will potentially impact the world through endeavors enhanced by private gifts. Over the 138-year life of Mississippi State University, outreach has become an exemplary hallmark of education in true land-grant institution tradition. From its inception, our university has extended its reach into the communities where people live and work as it shares significant strides in engagement and service with all. The university has a wide-range the role colleges and universities play in solving an every day basis, and provides endowments as a impact because of a statewide community problems and placing more students on perpetual way to fund our efforts long term. network of extension and outreach, lifelong paths of civic engagement. At this juncture, private gifts are imperative for T a role as the state’s flagship research At the heart of the Mississippi State beats Mississippi State, and a comprehensive campaign is institution, and a range of degree programs an unyielding commitment to student-centered providing the support needed to drive the university to educate its graduates. Moving forward, programs that address society’s emerging needs. toward its long-range goal of inclusion among those engagement and service remain among the greatest It is students who have a firsthand opportunity to public universities of national prominence. -

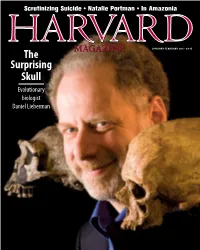

The Surprising Skull Evolutionary Biologist Daniel Lieberman Take It with You

Scrutinizing Suicide • Natalie Portman • In Amazonia january-february 2011 • $4.95 The Surprising Skull Evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman Take it with you. 5345 4777 0008 4857 Your Name Here GOOD 12/11 THRU You don’t have to leave Harvard in the Square. Show off your Harvard pride every time you use your HUECU Platinum MasterCard.® Customize your card with our simple design tool by uploading your favorite photo or choose an image from our online gallery featuring photos from around the Square. Plus, our Platinum MasterCard® comes with a 3.99% APR* balance transfer rate for the fi rst year. Visit us online at www.huecu.org for more information or to sign up today. Federally Insured by NCUA * Annual Percentage Rate. 3.99% APR is valid for www.huecu.org | 617.495.4460 the fi rst 12 billing cycles from the date of issue. HUECU_DYOC_HarvardMagAd.indd 1 11/29/10 2:10:56 PM JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2011 VOLUME 113, NUMBER 3 MEREDITH KEFFER MEREDITH page 57 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Head to Toe 2 Cambridge 02138 24 Communications from our readers The rapid and revealing evolution of the human skull 7 Right Now Virus-sized intracellular transistors, by Jonathan Shaw more sensitive measures of poverty, games children play—to master their Vita: Kermit Roosevelt emotions 30 Brief life of a Harvard conspirator: 12A New England 1916-2000 Regional Section by Gwen Kinkead Seasonal events, “Third Age” careers, page 36 and a novel take on Chinese cuisine JAKE BRYANT JAKE EARCHLIGHT PICTURES S A Tragedy and a Mystery OX OX 32 F 13 Montage Psychologist Matthew Nock -

FMI Member Search Results

FMI Member Search Results This search was performed on Oct 02 2021 at 01:20 AM The search criteria selected were as follows. If you find information that needs to be updated, please email [email protected]. Thank you. FMI 2345 Crystal Drive, Suite 800 Arlington, VA 22202 Phone: 202.452.8444 | Fax: 202.429.4519 84.51º 100 W. Fifth Street Cincinnati, OH 45202-2704 United States Main Phone: 513-632-0903 Web site: www.8451.com E-mail: [email protected] Description At 84.51º, we are obsessed with turning data into knowledge. By taking a unique longitudinal, long-term approach to data analytics, we provide a whole new depth of understanding and a higher level of insight for the partners and consumer brands we serve. We help our partners embed a customer-first attitude deeply (and broadly) throughout the organization to drive growth and enhance customer loyalty. (Parent Company: The Kroger Co.) A.J. Letizio Sales & Marketing, Inc. 55 Enterprise Drive Windham, NH 03087-2031 United States Main Phone: 603-894-4445 Web site: www.ajletizio.com Abundance Cooperative Market 571 South Avenue Rochester, NY 14620-1335 United States Main Phone: 585-454-2667 Web site: www.abundance.coop E-mail: [email protected] (Parent Company: National Co+op Grocers) Acme Fresh Markets 2700 Gilchrist Road Akron, OH 44305-4433 United States Main Phone: 330-733-2263 ext.55318 Web site: www.acmestores.com Description Acme is great (Parent Company: The Fred W. Albrecht Grocery Co.) ACME Markets 75 Valley Stream Parkway Malvern, PA 19355-1459 United States Main Phone: 610-889-4000 Web site: www.acmemarkets.com (Parent Company: Albertsons Companies) Action Food Sales, Inc. -

Buying for Workplace Equality 2016 a Few Ways You Can Help Fight Dear for Equality Every Day: Friends,Take Action for Equality

5 A Guide To Companies, Products And Services That Support Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual And Transgender Workplace Inclusion BUYING FOR WORKPLACE EQUALITY 2016 A FEW WAYS YOU CAN HELP FIGHT DEAR FOR EQUALITY EVERY DAY: FRIENDS,TAKE ACTION FOR EQUALITY Share this information with your friends, family and co-workers. Help them become supporters of workplace equality by factoring the information from this guide into 1 purchasing decisions. Advocate for equality in the work- place. If your company isn’t on this list or you think it can do better, go to www.hrc.org/cei to find out how to 2 engage your employer. Get active about equality. Sign up for newsletters and Action Alerts at 3 www.hrc.org/workplace. 1 The maxim that the customer is always right has never been truer in today’s hyper- connected global market. Consumers can publicly praise or criticize businesses they patronize with the click of a button and influence friends’ and strangers’ purchasing behaviors. Businesses cannot afford to ignore the increasingly savvy and engaged consumer. As consumers, you know that you have a choice. And with this Buying for Workplace Equality guide, providing the most accurate review of a business’s workplace policies toward lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender employees, we hope that you feel empowered to make those purchasing decisions that are most important to you. This year’s guide includes results from the 2016 Corporate Equality Index, which features 407 businesses that scored a perfect 100 percent. All scores are based on the same set of criteria, rating 40 LGBT-related policies, benefits and corporate practices among the largest US businesses. -

Product Guide Product

PRODUCT GUIDE PRODUCT 800.356.8881 [email protected] www.cdccoffee.com UNIT CASE SKU PRODUCT NAME CATEGORY COUNT COUNT 64976 Canada Dry Ginger Ale & Lemonade (12oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 26262 Canada Dry Tonic Water Glass Bottle (10oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 30531 Hint Blackberry Fizz Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 12 30529 Hint Peach Fizz Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 12 33181 Hint Strawberry Kiwi Fizz Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 12 28013 Hint Watermelon Fizz Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 12 5077 Perrier (11.15oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 7834 Perrier (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 10665 Perrier (6.75oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 20993 Perrier Lime Sparkling Water (11.15oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 13939 Perrier Sparkling Mineral Water (25.3oz) Beverages - Carb Water 12 12688 Perrier with Lemon Sparkling Water (11.15oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 43833 Poland Springs Black Cherry Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 5079 Poland Springs Lively Lemon Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 5080 Poland Springs Orange Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 5081 Poland Springs Raspberry Lime Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 5240 Poland Springs Simply Bubbles Original Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 5078 Poland Springs Zesty Lime Sparkling Water (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 26144 S. Pellegrino Sparkling Natural Mineral Water (25.3oz) Beverages - Carb Water 15 8292 S. Pellegrino Sparkling Natural Mineral Water Glass (16.9oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 5103 S. Pellegrino Sparkling Natural Mineral Water Glass Bottle (8.45oz) Beverages - Carb Water 24 9062 S. -

Download Our Catalog

EVANS COMPANY CALL NOW (201) 641-6000 www.evanscoffee.com VOLUME 2019-1 To Order Call: 201-641-6000 To Our Valued Customers I would like to thank you for your continued loyalty and business relationship with us. I would also like to thank you for the opportunity you have given The Evans Company to serve you over the last forty years. The Evans Company continues to be a driving force in the coffee, water, and vending business. Our gourmet coffees, teas, and cold beverages continue to dominate our sales. In the emerging spring water market, Evans Natural Spring Water has been an overwhelming smart choice for consumers in your home and office. We have always taken pride in offering top quality products and service at competitive prices. I welcome all suggestions you may have that will enable us to make The Evans Company of your choice. I would also like to take this opportunity to thank each and every one of my co-workers for their outstanding efforts and dedication to excellence. They are truly dedicated to you, our valued customer. I look forward to the challenge of satisfying your growing needs. Sincerely, Edward Evans (President) To Order Call: 201-641-6000 A Service Everyone Will Appreciate! A REPUTATION FOR EXCELLENCE The Evans Company is your one stop solution for all of your needs. We have everything you need including coffee service, state-of-the-art water service and the latest in automatic food and beverage vending. The Evans Company with cost savings along with the finest quality service available.