The Magdalene Veil Excerpt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pius XII on Trial

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Pius XII on Trial Katherine M. Campbell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Katherine M., "Pius XII on Trial" (2014). Honors College. 159. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/159 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIUS XII ON TRIAL by Katherine M. Campbell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology and Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Henry Munson, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Grab, Professor of History Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor of Political Science, Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Copyright 2014 Katherine M. Campbell Abstract: Scholars have debated Pope Pius XII’s role in the Holocaust since the 1960s. Did he do everything he could and should have done to save Jews? His critics say no because of antisemitism rooted in the traditional Catholic views. His defenders say yes and deny that he was an antisemite. In my thesis, I shall assess the arguments on both sides in terms of the available evidence. I shall focus both on what Pius XII did do and what he did not do and on the degree to which he can be held responsible for the actions of low-level clergy. -

Learning from the Aftermath of the Holocaust G

Learning From The Aftermath Of The Holocaust G. Short, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research [IJHLTR], Volume 14, Number 2 – Spring/Summer 2017 Historical Association of Great Britain www.history.org.uk ISSN: 14472-9474 Abstract: In this article I seek to encourage those involved in Holocaust education in schools to engage not just with the Holocaust but also with its aftermath. I conceptualise the latter in terms of two questions; namely, what happened to those Jews who survived the Nazi onslaught and what became of the perpetrators? British researchers in the field of Holocaust education have largely ignored these questions, discovering only that many schools ignore them too. I argue that students are able to benefit in a number of ways from learning about the aftermath of the Holocaust, for the topic provides a sense of closure, allows for a more sophisticated understanding of the fate of European Jewry between 1933 and 1945 and also has the potential to promote responsible citizenship. Keywords: Citizenship, Curriculum, Holocaust Aftermath, Learning, Teaching INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HISTORICAL LEARNING, TEACHING AND RESEARCH Vol. 14.2 LEARNING FROM THE AFTERMATH OF THE HOLOCAUST G. Short, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom Abstract: In this article I seek to encourage those involved in Holocaust education in schools to engage not just with the Holocaust but also with its aftermath. I conceptualise the latter in terms of two questions; namely, what happened to those Jews who survived the Nazi onslaught and what became of the perpetrators? British researchers in the field of Holocaust education have largely ignored these questions, discovering only that many schools ignore them too. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Pilgrims to Thule

MARBURG JOURNAL OF RELIGION, Vol. 22, No. 1 (2020) 1 Pilgrims to Thule: Religion and the Supernatural in Travel Literature about Iceland Matthias Egeler Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Abstract The depiction of religion, spirituality, and/or the ‘supernatural’ in travel writing, and more generally interconnections between religion and tourism, form a broad and growing field of research in the study of religions. This contribution presents the first study in this field that tackles tourism in and travel writing about Iceland. Using three contrasting pairs of German and English travelogues from the 1890s, the 1930s, and the 2010s, it illustrates a number of shared trends in the treatment of religion, religious history, and the supernatural in German and English travel writing about Iceland, as well as a shift that happened in recent decades, where the interests of travel writers seem to have undergone a marked change and Iceland appears to have turned from a land of ancient Northern mythology into a country ‘where people still believe in elves’. The article tentatively correlates this shift with a change in the Icelandic self-representation, highlights a number of questions arising from both this shift and its seeming correlation with Icelandic strategies of tourism marketing, and notes a number of perspectives in which Iceland can be a highly relevant topic for the research field of religion and tourism. Introduction England and Germany have long shared a deep fascination with Iceland. In spite of Iceland’s location far out in the North Atlantic and the comparative inaccessibility that this entailed, travellers wealthy enough to afford the long overseas passage started flocking to the country even in the first half of the nineteenth century. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

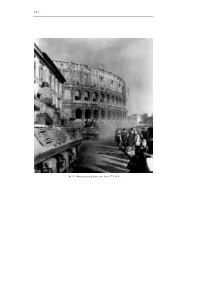

The US-Army Entering Rome on June 4Th 1944

514 The US-Army entering Rome on June 4th 1944 “Tomorrow John Kitterer will play”: The SOE Operation Duval 515 Peter Pirker “Tomorrow John Kitterer will play” The SOE Operation Duval and the Mauthausen Survivors Josef Hemetsberger and Hans Prager1 When the US and British Armies marched into Rome on June 4, 1944 there was finally an opportunity for two deserters of the German Wehrmacht to come out of hiding respectively leave their precarious situation with the partisans behind and act openly: Josef Hemets- berger, then 23 years old, and Hans Prager, then 18 years old, went to the house of the former Austrian embassy in Rome without knowing of each other. Prager was responding to a newspaper announcement which encouraged all Austrians in Rome to take this step; Hemetsberger followed a long harboured wish to join an Austrian legion which was, ac- cording to rumours at home, led by the former Heimwehrführer (Home Guard leader) Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg and would fight for the reinstallation of an independent Austria on the sides of the Allied Forces. Both were considerably surprised when they were met by American soldiers and taken into custody. Until recently, the building in the Via Perigolesi had been the re- gional headquarters of the foreign NSDAP. Two days after the liberation of Rome the building was occupied by a group of Aus- trians, among them Bishop Hudal and the last Austrian ambassa- dor in Italy and former foreign minister in the Schuschnigg government, Egon Berger-Waldenegg. They flagged the building with the red and white Austrian flag and the banner “Es lebe das freie und alliierte Österreich” (Long live the free and allied Austria).2 At the same time rumours were spread that the Allied Forces were already Bishop Alois Hudal envisaging Berger-Waldenegg as head of a future Austrian gov- ernment.3 After a couple of days, the Allied military police cleared the building after pro- tests from left-wing and middle-class exile organisations in Great Britain and the USA and harsh criticism of the British press. -

Dos Décadas Han Trascurrido Desde El Inicio De Un Acceso

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CONICET Digital Nazis Y charlatanes en Argentina. ACERCA DE Mitos E historia TERGIVersada IGNACIO KLICH (Universidad de Buenos Aires) CRISTIAN BUCHRUCKER (CONICET, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo) Dos décadas han trascurrido desde el currido ocasional y selectivamente a una inicio de un acceso más fluido a la docu- cantidad insignificante de documentos, mentación sobre los nazis acumulada en priorizando hallazgos personales de difícil distintos repositorios argentinos. Si bien consulta por terceros, salvo para quienes tardía, esta medida propicia, primero efec- se den por satisfechos con las copias facsi- tivizada no más que apenas, luego con milares ocasionalmente reproducidas por mayor amplitud, comenzó a verse imple- tales periodistas, y citando a los demás de mentada a partir de 1992. Desde entonces, manera indirecta y descontextualizada. el grueso de la producción sobre esta vasta Un caso más extremo de la misma falta es temática –básicamente la del periodismo el de quienes escriben con casi la más ab- investigativo local– ha dado pocas señales soluta prescindencia de la documentación de haberse servido del consecuente acreci- e historiografía, como si se pudiese lograr miento de la materia prima disponible. un texto de historia seria a puro artificio, La calidad de gran parte de esa produc- con asertos cuya validez está más allá del ción periodística revela, en todo caso, que aporte de evidencia firme en su apoyo. ella no ha abrevado demasiado en tan rica, Como posible justificación de tan limita- aún si incompleta, fuente. En rigor, tales do aprovechamiento de los registros dispo- escritos se produjeron mayormente con nibles, no escasean las alusiones a «miles y prescindencia de casi todo el material de miles de documentos» más, «guardados en archivos argentinos y extranjeros, como si inasibles archivos que nadie tiene interés estos papeles no existiesen o el acceso a en mostrar y que son difíciles de hallar»1. -

Tango Mortale

Tango mortale Eine Lange Nacht über Argentinien und die Schatten seiner Vergangenheit Autorin: Margot Litten Regie: die Autorin Redaktion: Dr. Monika Künzel SprecherInnen: Julia Fischer (Erzählerin) Christian Baumann Krista Posch Andreas Neumann Rahel Comtesse Sendetermine: 27. März 2021 Deutschlandfunk Kultur 27./28. März 2021 Deutschlandfunk __________________________________________________________________________ Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis: Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Jede Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in den §§ 45 bis 63 Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig. © Deutschlandradio - unkorrigiertes Exemplar - insofern zutreffend. 1. Stunde Musik geht über in Atmo Menschenmenge vor Kongress Sprecher Eine wogene Menschenmenge vor dem Kongresspalast im Zentrum von Buenos Aires - Frauen mit grünen Halstüchern, dem Symbol ihres Kampfes für eine Legalisierung von Schwangerschaftsabbrüchen. Seit Jahren sorgt das Thema für heftige Debatten in dem katholisch geprägten Land. Nach zwölfstündiger Marathonsitzung stimmt der Senat tatsächlich für das Recht auf Abtreibung, obwohl sogar Papst Franziskus in letzter Minute per Twitter versucht hat, das Blatt zu wenden. Draußen brandet Jubel auf, die Frauen lachen, weinen, umarmen sich … ein historischer Tag, dieser 30. Dezember 2020. Eines der großen Tabus in Lateinamerika ist gebrochen. Atmo Menschenmenge nochmal kurz hoch / dann darüber: Auch -

Pasado Mañana Se Reinician En San Rafael Los Juicios Por Crímenes De Lesa Humanidad

Año 5 Nro. 272 $ 3 Malargüe, Mendoza, Argentina, Sábado 27 de diciembre de 2014 www.sinpelos2011.wordpress.com Dirección electrónica: [email protected] Pasado mañana se reinician en San Rafael los juicios por crímenes de lesa humanidad Los cursos El INADI pidió al Concejo Deliberan- te, a la DGE y al Instituto del Verbo de DDHH co- Encarnado que retire las imágines re- menzaran en ligiosas en los espacios públicos. No Malargüe el se pueden rezar oracio- nes católicas en las es- 18 de abril cuelas públicas y el cura Pato Gómez no puede dar misa en la escuela de Bardas Blancas FE de ERRATAS: en nuestro número anterior metimos la pata con las fechas de SPELL. Pedimos disculpas e informamos que nos tomamos un descanso y que nuestro próximo número verá la luz el sábado 17 de enero, con un informe completo sobre los juicios por crímenes de lesa humanidad en San Rafael Los temas de esta semana Este lunes comienzan los juicios en San Rafael y la APDH se perfila como factor de poder de militancia social (pág. 2); Nuevos links a los DDHH (pág. 2); Nuevo dictamen del INADI a favor del laicismo (pág. 3); Ya tienen fecha los cursos 2015 de la APDH (pág. 3); Carlos Raimundi expli- ca por qué los juicios no deben caerse (pág. 4); ODESSA y el Instituto del Verbo Encarnado (pág. 5); Un miembro del IVE es hijo de un represor sanjuanino prófugo (pág. 7); La concejal Martínez nos informó de sus proyectos (pág. 7); GREENPEACE logró parar los desmontes (pág. -

PLM5340 Fringe Politics and Extremist Violence

1 From Wewelsburg to Project Monarch: Anatomy of a Fringe Violence Conspiracy Alex Burns ([email protected]), June 2005 Abstract In 1982 the Temple of Set (ToS) a pre-eminent ‘Satanic’ religious institution faced an initiatory crisis. Its senior initiate Dr. Michael A. Aquino travelled to Heinrich Himmler’s Wewelsburg castle to reflect on the ethical and philosophical implications of the crisis. The resulting document, a reflective meditation known as the ‘Wewelsburg Working’, later became controversial when it was leaked to Christian fundamentalist, Patriot militia, the Larouche movement and cult awareness communities. This essay examines the Wewelsburg Current as a case study in how social diffusion of ‘forbidden knowledge’ may create unforeseen effects and why the document was interpreted differently by new religious groups, media pundits, law enforcement officials and extremist political subcultures. The sources include publicly available literature, hermeneutic interpretation of internal documents, and reflexive heuristic inquiry (this addresses issues of research subjectivity given the author’s ToS membership between 1996 and 1998). It also draws on insights about the broader ‘Nazi Occult’ subculture by Joscelyn Godwin, Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Mark Jonathan Rogers, Stephen Edred Flowers and Peter Levenda. The essay identifies four key problems for future research. First, researchers of extremist politics will need to be familiar with reflexive embodied research. Second, critical layered methods are required to evaluate different interpretations of knowledge claims. Third, the social diffusion of ‘forbidden knowledge’ often creates crises that rival the nuclear proliferation debate. Fourth, the ‘Wewelsburg Working’ has ethical implications about confronting the ontological nature of radical evil in an era Michael Ignatieff defines as ‘virtual war’. -

Kirsten John-Stucke Wewelsburg Castle

IC Memo, 5th July 2016 Kirsten John-Stucke Wewelsburg Castle – an attraction pole of Dark Tourism – How to deal with this phenomenon at a memorial site Before beginning with the field of tension that is the myth of Wewelsburg – Dark Tourism and its responses, I would first like to explain the history of the Wewelsburg in the Third Reich. About the history of the Wewelsburg The Renaissance castle was built at the beginning of the 17th century as a second official residence for the Paderborn prince-bishops. The triangular form is due to its position on the peak of a spur above the Alme valley. Due to secularisation of the Paderborn bishopric in 1802, ownership of the castle was transferred to the Prussian state. The Wewelsburg then only served as a storage hall for grain duties and as living quarters for the bursary officer and catholic priest. The former district of Büren took over the building in the 1920s from the state property administration. Influenced by the Catholic youth and homeland movement, the district authorities expanded the castle to become a centre of culture with a youth hostel, homeland museum and conference location.1 In the early 1930s, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler was searching for a site for an own SS Reichsführer school in the Lippe Westphalia region, and he saw Westphalia Lippe to be the Saxon heartland of Germania, the alleged home country of the "Arian northern race". Himmler began to rent the castle from June 1934 onwards. Instead of training operations, the head of the castle garrison Manfred von Knobelsdorff initially set up scientific research activities. -

Wewelsburg 1933

KREISMUSEUM WEWELSBURG Historisches Museum des Hochstifts Paderborn Wewelsburg 1933 – 1945 Erinnerungs- und Gedenkstätte Historical Museum of the Prince Bishopric of Paderborn Wewelsburg 1933 – 1945 Memorial Museum Historisch museum van het Prinsbisdom Paderborn Herinneringscentrum Wewelsburg 1933 – 1945 Die Wewelsburg wurde 1603 bis 1609 in ihrer einzigartigen Dreiecksform im Stil der Weserrenaissance von Fürstbischof Dietrich von Fürstenberg Wewelsburg Castle was rebuilt between 1603 and 1609 in its unique triangular shape in unter Einbeziehung älterer Bauten neu the Weser Renaissance style by Prince Bishop errichtet. Sie liegt hoch über dem Almetal Dietrich von Fürstenberg, incorporating older auf einem Bergsporn. buildings. It lies high above the Alme valley on a mountain spur. Today, Wewelsburg Castle Heute befindet sich in derW ewelsburg is home to a youth hostel and the District neben einer Jugendherberge das Kreismuseum Museum with its two museum departments: the Historical Museum of the Prince-Bishopric mit seinen zwei Museumsabteilungen: of Paderborn and the Wewelsburg 1933 – 1945 dem Historischen Museum des Hochstifts Memorial Museum. Regular special exhibi- Paderborn und der Erinnerungs- und Gedenk- tions and events complete the offer. stätte Wewelsburg 1933–1945. Regelmäßige De Wewelsburg werd tussen 1603 en 1609 in Sonderausstellungen und -veranstaltungen zijn unieke driehoekige vorm in de stijl van runden das Angebot ab. de Weserrenaissance gebouwd door prins- bisschop Dietrich von Fürstenberg, waarbij gebruik werd gemaakt van al be staande ge- bouwen. Hij ligt hoog boven het dal van de Alme op een bergrug. Tegenwoordig herbergt de Wewelsburg een jeugdherberg en het Kreismuseum met zijn twee museumafde- lingen: het Historisch Museum van het Prins- bisdom Paderborn en het Herinneringscen- trum Wewelsburg 1933 – 1945.