A Concise History of the US Air Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Files on the Famous–And Infamous

Federal Files on the Famous–and Infamous The collections of personnel records at the National Archives available. Digital copies of PEPs can be purchased on CD/DVDs. include files that document military and civilian service for The price of the disc depends on the number of pages contained persons who are well known to the public for many reasons. in the original paper record and range from $20 (100 pages or These individuals include celebrated military leaders, less) to $250 (more than 1,800 pages). For more information or Medal of Honor recipients, U.S. Presidents, members of to order copies of digitized PEP records only, please write to pep. Congress, other government officials, scientists, artists, [email protected]. Archival staff are in the process of identifying entertainers, and sports figures—individuals noted for the records of prominent civilian employees whose names will personal accomplishments as well as persons known for their be added to the list. Other individuals whose records are now infamous activities. available for purchase on CD are: The military service departments and NARA have Creighton W. Abrams, Grover Cleveland Alexander, identified over 500 such military records for individuals Desi Arnaz, Joe L. Barrow, John M. Birch, Hugo L. Black, referred to as “Persons of Exceptional Prominence” (PEP). Gregory Boyington, Prescott S. Bush, Smedley Butler, Evans Many of these records are now open to the public earlier F. Carlson, William A. Carter, Adna R. Chaffee, Claire than they otherwise would have been (62 years after the Chennault, Mark W. Clark, Benjamin O. Davis. separation dates) as the result of a special agreement that Also, George Dewey, William Donovan, James H. -

General Carl A. Spaatz

SCHOLARSHIP IN HONOR OF GENERAL CARL A. SPAATZ U.S. AIR FORCE General Carl A. Spaatz The story of the life of General Carl A. over Los Angeles and vicinity January 1-7, 1929, Spaatz is the story of military aviation in keeping the plane aloft a record total of 150 hours, the United States. 50 minutes and 15 seconds, and was awarded the T Distinguished Flying Cross. Carl Spaatz was born June 28, 1891, in Boyertown, Pennsylvania. In 1910, he was appointed to the From May 1, 1929, to October 29, 1931, General United States Military Academy from which he Spaatz commanded the Seventh Bombardment was graduated June 12, 1914 and commissioned Group at Rockwell Field, California, and the First a 2nd Lt. of Infantry. He served with the Twen- Bombardment Wing at March Field, California, ty-Fifth United States Infantry at Schofield Bar- until June 10, 1933. He then served in the Office racks, Hawaii, from October 4, 1914, to October of the Chief of Air Corps and became Chief of the 13, 1915, when he was detailed as a student in the Training and Operations Division. Aviation School at San Diego, California, until May 15, 1916. In January 1942, General Spaatz was assigned as Chief of the AAF Combat Command at Wash- In June 1916, General Spaatz was assigned at Co- ington. In May 1942, he became Commander lumbus, New Mexico, and served with the First of the Eighth Air Force, transferring to the Eu- Aero Squadron under General John J. Pershing in ropean theater of operations in that capacity in the Punitive Expedition into Mexico. -

Reflections and 1Rememb Irancees

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution IJnlimiter' The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II REFLECTIONS AND 1REMEMB IRANCEES Veterans of die United States Army Air Forces Reminisce about World War II Edited by William T. Y'Blood, Jacob Neufeld, and Mary Lee Jefferson •9.RCEAIR ueulm PROGRAM 2000 20050429 011 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved I OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of Information Is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 2000 na/ 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Reflections and Rememberances: Veterans of the US Army Air Forces n/a Reminisce about WWII 5b. GRANT NUMBER n/a 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER n/a 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Y'Blood, William T.; Neufeld, Jacob; and Jefferson, Mary Lee, editors. -

AIRLIFT RODEO a Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989

"- - ·· - - ( AIRLIFT RODEO A Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989 Office of MAC History Monograph by JefferyS. Underwood Military Airlift Command United States Air Force Scott Air Force Base, Illinois March 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword . iii Introduction . 1 CARP Rodeo: First Airdrop Competitions .............. 1 New Airplanes, New Competitions ....... .. .. ... ... 10 Return of the Rodeo . 16 A New Name and a New Orientation ..... ........... 24 The Future of AIRLIFT RODEO . ... .. .. ..... .. .... 25 Appendix I .. .... ................. .. .. .. ... ... 27 Appendix II ... ...... ........... .. ..... ..... .. 28 Appendix III .. .. ................... ... .. 29 ii FOREWORD Not long after the Military Air Transport Service received its air drop mission in the mid-1950s, MATS senior commanders speculated that the importance of the new airdrop mission might be enhanced through a tactical training competition conducted on a recurring basis. Their idea came to fruition in 1962 when MATS held its first airdrop training competition. For the next several years the competition remained an annual event, but it fell by the wayside during the years of the United States' most intense participation in the Southeast Asia conflict. The airdrop competitions were reinstated in 1969 but were halted again in 1973, because of budget cuts and the reduced emphasis being given to airdrop operations. However, the esprit de corps engendered among the troops and the training benefits derived from the earlier events were not forgotten and prompted the competition's renewal in 1979 in its present form. Since 1979 the Rodeos have remained an important training event and tactical evaluation exercise for the Military Airlift Command. The following historical study deals with the origins, evolution, and results of the tactical airlift competitions in MATS and MAC. -

Getting the Philippines Air Force Flying Again: the Role of the U.S.–Philippines Alliance Renato Cruz De Castro, Phd, and Walter Lohman

BACKGROUNDER No. 2733 | SEptEMBER 24, 2012 Getting the Philippines Air Force Flying Again: The Role of the U.S.–Philippines Alliance Renato Cruz De Castro, PhD, and Walter Lohman Abstract or two years, the U.S.– The recent standoff at Scarborough FPhilippines alliance has been Key Points Shoal between the Philippines and challenged in ways unseen since the China demonstrates how Beijing is closure of two American bases on ■■ The U.S. needs a fully capable ally targeting Manila in its strategy of Filipino territory in the early 1990s.1 in the South China Sea to protect U.S.–Philippines interests. maritime brinkmanship. Manila’s China’s aggressive, well-resourced weakness stems from the Philippine pursuit of its territorial claims in ■■ The Philippines Air Force is in a Air Force’s (PAF) lack of air- the South China Sea has brought a deplorable state—it does not have defense system and air-surveillance thousand nautical miles from its the capability to effectively moni- tor, let alone defend, Philippine capabilities to patrol and protect own shores, and very close to the airspace. Philippine airspace and maritime Philippines. ■■ territory. The PAF’s deplorable state For the Philippines, sovereignty, The Philippines has no fighter jets. As a result, it also lacks trained is attributed to the Armed Forces access to energy, and fishing grounds fighter pilots, logistics training, of the Philippines’ single-minded are at stake. For the U.S., its role as and associated basing facilities. focus on internal security since 2001. regional guarantor of peace, secu- ■■ The government of the Philippines Currently, the Aquino administration rity, and freedom of the seas is being is engaged in a serious effort to is undertaking a major reform challenged—as well as its reliability more fully resource its military to shift the PAF from its focus on as an ally. -

The WWI Lafayette Escadrille with David Ellison

Volume 22, Issue 7 ● September 2007 A Monthly Publication of the Pine Mountain Lake Aviation Association “Flyboys” – the WWI Lafayette Escadrille with David Ellison n 1914, "The Great War," World War I began in Europe. By 1917, the Allied powers of France, England, IItaly and others were on the ropes against the German juggernaut. America chose, at first, not to fight. Some young Americans disagreed. They volunteered to fight alongside their counterparts in France: some in the infantry, some in the Ambulance Corps. A handful of others had a different idea: they decided to learn to fly. The first of A real-life aviator and aerobatic pilot, Ellison began flying them - a squadron of only 38 - became known as the when he was 13 years old and performs at air-shows Lafayette Escadrille. In time, America joined their cause. around the world. In 2003 Ellison was chosen as one of the The Escadrille pilots became legendary. Flyboys is inspired "Stars of Tomorrow," six of the best aerobatic pilots in the by their story. country who displayed their ability to loop, roll, tumble, and free-fall at Oshkosh. In competition, Ellison flies a French Flyboys is the first film in decades to bring the story of the CAP 232, the world's premiere aerobatic aircraft and the famous World War I squadron to the big screen. The film plane of choice for the world's best aerobatic pilots. He is examines the lives of the young American men who the son of Larry Ellison, co-founder and CEO of Oracle volunteered to join French soldiers in battling Germany Corporation and has trained with Wayne Handley. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

OH-323) 482 Pgs

Processed by: EWH LEE Date: 10-13-94 LEE, WILLIAM L. (OH-323) 482 pgs. OPEN Military associate of General Eisenhower; organizer of Philippine Air Force under Douglas MacArthur, 1935-38 Interview in 3 parts: Part I: 1-211; Part II: 212-368; Part III: 369-482 DESCRIPTION: [Interview is based on diary entries and is very informal. Mrs. Lee is present and makes occasional comments.] PART I: Identification of and comments about various figures and locations in film footage taken in the Philippines during the 1930's; flying training and equipment used at Camp Murphy; Jimmy Ord; building an airstrip; planes used for training; Lee's background (including early duty assignments; volunteering for assignment to the Philippines); organizing and developing the Philippine Air Unit of the constabulary (including Filipino officer assistants; Curtis Lambert; acquiring training aircraft); arrival of General Douglas MacArthur and staff (October 26, 1935); first meeting with Major Eisenhower (December 14, 1935); purpose of the constabulary; Lee's financial situation; building Camp Murphy (including problems; plans for the air unit; aircraft); Lee's interest in a squadron of airplanes for patrol of coastline vs. MacArthur's plan for seapatrol boats; Sid Huff; establishing the air unit (including determining the kind of airplanes needed; establishing physical standards for Filipino cadets; Jesus Villamor; standards of training; Lee's assessment of the success of Filipino student pilots); "Lefty" Parker, Lee, and Eisenhower's solo flight; early stages in formation -

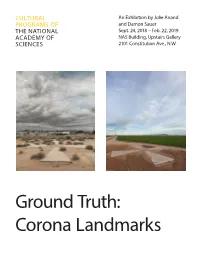

Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks an Introduction

CULTURAL An Exhibition by Julie Anand PROGRAMS OF and Damon Sauer THE NATIONAL Sept. 24, 2018 – Feb. 22, 2019 ACADEMY OF NAS Building, Upstairs Gallery SCIENCES 2101 Constitution Ave., N.W. Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks An Introduction In this series of images of what remains of the Corona project, Julie Anand and Damon Sauer investigate our relationship to the vast networks of information that encircle the globe. The Corona project was a CIA and U.S. Air Force surveillance initiative that began in 1959 and ended in 1972. It involved using cameras on satellites to take aerial photographs of the Soviet Union and China. The cameras were calibrated with concrete targets on the ground that are 60 feet in diameter, which provided a reference for scale and ensured images were in focus. Approximately 273 of these concrete targets were placed on a 16-square-mile grid in the Arizona des- ert, spaced a mile apart. Long after Corona’s end and its declassification in 1995, around 180 remain, and Anand and Sauer have spent three years photographing them as part of an ongoing project. In their images, each concrete target is overpowered by an expansive sky, onto which the artists map the paths of orbiting satellites that were present at the Calibration Mark AG49 with Satellites moment the photograph was taken. For Anand and 2016 Sauer, “these markers of space have become archival pigment print markers of time, representing a poignant moment 55 x 44 inches in geopolitical and technologic social history.” A few of the calibration markers like this one are made primarily of rock rather than concrete. -

Air and Space Power Journal: Fall 2011

Fall 2011 Volume XXV, No. 3 AFRP 10-1 From the Editor Personnel Recovery in Focus ❙ 6 Lt Col David H. Sanchez, Deputy Chief, Professional Journals Capt Wm. Howard, Editor Senior Leader Perspective Air Force Personnel Recovery as a Service Core Function ❙ 7 It’s Not “Your Father’s Combat Search and Rescue” Brig Gen Kenneth E. Todorov, USAF Col Glenn H. Hecht, USAF Features Air Force Rescue ❙ 16 A Multirole Force for a Complex World Col Jason L. Hanover, USAF Department of Defense (DOD) Directive 3002.01E, Personnel Recovery in the Department of Defense, highlights personnel recovery (PR) as one of the DOD’s highest priorities. As an Air Force core function, PR has experienced tremendous success, having performed 9,000 joint/multinational combat saves in the last two years and having flown a total of 15,750 sorties since 11 September 2001. Despite this admirable record, the author contends that the declining readiness of aircraft and equipment as well as chronic staffing shortages prevents Air Force rescue from meeting the requirements of combatant commanders around the globe. To halt rescue’s decline, a numbered Air Force must represent this core function, there- by ensuring strong advocacy and adequate resources for this lifesaving, DOD-mandated function. Strategic Rescue ❙ 26 Vectoring Airpower Advocates to Embrace the Real Value of Personnel Recovery Maj Chad Sterr, USAF The Air Force rescue community has expanded beyond its traditional image of rescuing downed air- crews to encompass a much larger set of capabilities and competencies that have strategic impact on US operations around the world. -

The Aeronautical Division, US Signal Corps By

The First Air Force: The Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps By: Hannah Chan, FAA history intern The United States first used aviation warfare during the Civil War with the Union Army Balloon Corps (see Civil War Ballooning: The First U.S. War Fought on Land, at Sea, and in the Air). The lighter-than-air balloons helped to gather intelligence and accurately aim artillery. The Army dissolved the Balloon Corps in 1863, but it established a balloon section within the U.S. Signal Corps, the Army’s communication branch, during the Spanish-American War in 1892. This section contained only one balloon, but it successfully made several flights and even went to Cuba. However, the Army dissolved the section after the war in 1898, allowing the possibility of military aeronautics advancement to fade into the background. The Wright brothers' successful 1903 flight at Kitty Hawk was a catalyst for aviation innovation. Aviation pioneers, such as the Wright Brothers and Glenn Curtiss, began to build heavier-than-air aircraft. Aviation accomplishments with the dirigible and planes, as well as communication innovations, caused U.S. Army Brigadier General James Allen, Chief Signal Officer of the Army, to create an Aeronautical Division on August 1, 1907. The A Signal Corps Balloon at the Aeronautics Division division was to “have charge of all matters Balloon Shed at Fort Myer, VA Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum pertaining to military ballooning, air machines, and all kindred subjects.” At its creation, the division consisted of three people: Captain (Capt.) Charles deForest Chandler, head of the division, Corporal (Cpl.) Edward Ward, and First-class Private (Pfc.) Joseph E. -

Aircraft of Today. Aerospace Education I

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 287 SE 014 551 AUTHOR Sayler, D. S. TITLE Aircraft of Today. Aerospace EducationI. INSTITUTION Air Univ.,, Maxwell AFB, Ala. JuniorReserve Office Training Corps. SPONS AGENCY Department of Defense, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 179p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Education; *Aerospace Technology; Instruction; National Defense; *PhysicalSciences; *Resource Materials; Supplementary Textbooks; *Textbooks ABSTRACT This textbook gives a brief idea aboutthe modern aircraft used in defense and forcommercial purposes. Aerospace technology in its present form has developedalong certain basic principles of aerodynamic forces. Differentparts in an airplane have different functions to balance theaircraft in air, provide a thrust, and control the general mechanisms.Profusely illustrated descriptions provide a picture of whatkinds of aircraft are used for cargo, passenger travel, bombing, and supersonicflights. Propulsion principles and descriptions of differentkinds of engines are quite helpful. At the end of each chapter,new terminology is listed. The book is not available on the market andis to be used only in the Air Force ROTC program. (PS) SC AEROSPACE EDUCATION I U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO OUCH) EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN 'IONS STATED 00 NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EOU CATION POSITION OR POLICY AIR FORCE JUNIOR ROTC MR,UNIVERS17/14AXWELL MR FORCEBASE, ALABAMA Aerospace Education I Aircraft of Today D. S. Sayler Academic Publications Division 3825th Support Group (Academic) AIR FORCE JUNIOR ROTC AIR UNIVERSITY MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE, ALABAMA 2 1971 Thispublication has been reviewed and approvedby competent personnel of the preparing command in accordance with current directiveson doctrine, policy, essentiality, propriety, and quality.