Malaso of Madagascar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar Is Recruiting for the Following Position

The United States Peace Corps/Madagascar is recruiting for the following position: TEMPORARY LANGUAGE AND CROSS-CULTURAL FACILITATORS (LCF) The position is based at the Peace Corps Training Center, in Mantasoa, and is a short-term contract (typically 10 to 14 weeks). The primary role of the LCF is to train American trainees and volunteers in the Malagasy language and culture. Training usually take place at a residential training facilities where both LCFs and trainees/volunteers stay full-time. LCFs work under the direct supervision of Peace Corps Madagascar’s Language Coordinator. The duties of the LCF include, but are not limited to: Conduct Malagasy language training classes with small groups of American trainees or volunteers. Participate in the preparation of language training materials or resources. Conduct formal sessions and provide ongoing informal instruction and advice to trainees/volunteers regarding cultural adaptation and culturally appropriate behavior Interact with trainees outside of the classroom setting, providing informal training during meals, social events and other periods outside of classroom training Actively participate in staff language training Serve as the cultural model and guide for trainees/volunteers within their communities Establish and maintain a healthy, productive team spirit among the language staff and between support staff and Volunteer trainers Occasionally serve as Malagasy and English interpreters and/or translators. As requested, install the new Volunteers at their permanent sites; and train their community-based tutor as needed Required Qualifications: Completion of secondary school (Minimum BACC) Fluency in English, French and Malagasy Mastery in at least one of the following dialects: Betsileo, Antakarana, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antesaka, Antefasy, Sakalava boina, Antanosy, Antandroy, Sihanaka, Mahafaly, Bara. -

Evaluating the Effects of Colonialism on Deforestation in Madagascar: a Social and Environmental History

Evaluating the Effects of Colonialism on Deforestation in Madagascar: A Social and Environmental History Claudia Randrup Candidate for Honors in History Michael Fisher, Thesis Advisor Oberlin College Spring 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Methods and Historiography Chapter 1: Deforestation as an Environmental Issue.……………………………………… 20 The Geography of Madagascar Early Human Settlement Deforestation Chapter 2: Madagascar: The French Colony, the Forested Island…………………………. 28 Pre-Colonial Imperial History Becoming a French Colony Elements of a Colonial State Chapter 3: Appropriation and Exclusion…………………………………………………... 38 Resource Appropriation via Commercial Agriculture and Logging Concessions Rhetoric and Restriction: Madagascar’s First Protected Areas Chapter 4: Attitudes and Approaches to Forest Resources and Conservation…………….. 50 Tensions Mounting: Political Unrest Post-Colonial History and Environmental Trends Chapter 5: A New Era in Conservation?…………………………………………………... 59 The Legacy of Colonialism Cultural Conservation: The Case of Analafaly Looking Forward: Policy Recommendations Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………. 67 Selected Bibliography……………………………………………………………………… 69 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper was made possible by a number of individuals and institutions. An Artz grant and a Jerome Davis grant through Oberlin College’s History department and a Doris Baron Student Research Fund award through the Environmental Studies department supported -

Rep 2 out Public 2010 S Tlet Sur of Ma Urvey Rvey Adagas Repor Scar Rt

Evidence for Malaria Medicines Policy Outlet Survey Republic of Madagascar 2010 Survey Report MINSTERE DE LA SANTE PUBLIQUE www. ACTwatch.info Copyright © 2010 Population Services International (PSI). All rights reserved. Acknowledgements ACTwatch is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. This study was implemented by Population Services International (PSI). ACTwatch’s Advisory Committee: Mr. Suprotik Basu Advisor to the UN Secretary General's Special Envoy for Malaria Mr. Rik Bosman Supply Chain Expert, Former Senior Vice President, Unilever Ms. Renia Coghlan Global Access Associate Director, Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) Dr. Thom Eisele Assistant Professor, Tulane University Mr. Louis Da Gama Malaria Advocacy & Communications Director, Global Health Advocates Dr. Paul Lavani Executive Director, RaPID Pharmacovigilance Program Dr. Ramanan Senior Fellow, Resources for the Future Dr. Matthew Lynch Project Director, VOICES, Johns Hopkins University Centre for Dr. Bernard Nahlen Deputy Coordinator, President's Malaria Initiative (PMI) Dr. Jayesh M. Pandit Head, Pharmacovigilance Department, Pharmacy and Poisons Board‐Kenya Dr. Melanie Renshaw Advisor to the UN Secretary General's Special Envoy for Malaria Mr. Oliver Sabot Vice‐President, Vaccines Clinton Foundation Ms. Rima Shretta Senior Program Associate, Strengthening Pharmaceutical Systems Dr. Rick Steketee Science Director, Malaria Control and Evaluation Partnership in Africa Dr. Warren Stevens Health Economist Dr. Gladys Tetteh CDC Resident Advisor, President’s Malaria -

Boissiera 71

Taxonomic treatment of Abrahamia Randrian. & Lowry, a new genus of Anacardiaceae BOISSIERA from Madagascar Armand RANDRIANASOLO, Porter P. LOWRY II & George E. SCHATZ 71 BOISSIERA vol.71 Director Pierre-André Loizeau Editor-in-chief Martin W. Callmander Guest editor of Patrick Perret this volume Graphic Design Matthieu Berthod Author instructions for www.ville-ge.ch/cjb/publications_boissiera.php manuscript submissions Boissiera 71 was published on 27 December 2017 © CONSERVATOIRE ET JARDIN BOTANIQUES DE LA VILLE DE GENÈVE BOISSIERA Systematic Botany Monographs vol.71 Boissiera is indexed in: BIOSIS ® ISSN 0373-2975 / ISBN 978-2-8277-0087-5 Taxonomic treatment of Abrahamia Randrian. & Lowry, a new genus of Anacardiaceae from Madagascar Armand Randrianasolo Porter P. Lowry II George E. Schatz Addresses of the authors AR William L. Brown Center, Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, MO, 63166-0299, U.S.A. [email protected] PPL Africa and Madagascar Program, Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, MO, 63166-0299, U.S.A. Institut de Systématique, Evolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), UMR 7205, Centre national de la Recherche scientifique/Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle/École pratique des Hautes Etudes, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Sorbonne Universités, C.P. 39, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris CEDEX 05, France. GES Africa and Madagascar Program, Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, MO, 63166-0299, U.S.A. Taxonomic treatment of Abrahamia (Anacardiaceae) 7 Abstract he Malagasy endemic genus Abrahamia Randrian. & Lowry (Anacardiaceae) is T described and a taxonomic revision is presented in which 34 species are recog- nized, including 19 that are described as new. -

A Taxonomic Revision of Melanoxerus (Rubiaceae), with Descriptions of Three New Species of Trees from Madagascar

A taxonomic revision of Melanoxerus (Rubiaceae), with descriptions of three new species of trees from Madagascar Kent Kainulainen Abstract KAINULAINEN, K. (2021). A taxonomic revision of Melanoxerus (Rubiaceae), with descriptions of three new species of trees from Madagascar. Candollea 76: 105 – 116. In English, English and French abstracts. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15553/c2021v761a11 This paper provides a taxonomic revision of Melanoxerus Kainul. & Bremer (Rubiaceae) – a genus of deciduous trees with eye-catching flowers and fruits that is endemic to Madagascar. Descriptions of three new species, Melanoxerus antsirananensis Kainul., Melanoxerus atropurpureus Kainul., and Melanoxerus maritimus Kainul. are presented along with distribution maps and a species identification key. The species distributions generally reflect the ecoregions of Madagascar, with Melanoxerus antsirananensis being found in the dry deciduous forests of the north; Melanoxerus atropurpureus in the inland dry deciduous forests of the west; Melanoxerus maritimus in dry deciduous forest on coastal sands; and Melanoxerus suavissimus (Homolle ex Cavaco) Kainul. & B. Bremer in the dry spiny thicket and succulent woodlands of the southwest. Résumé KAINULAINEN, K. (2021). Révision taxonomique du genre Melanoxerus (Rubiaceae), avec la description de trois nouvelles espèces d’arbres de Madagascar. Candollea 76: 105 – 116. En anglais, résumés anglais et français. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15553/c2021v761a11 Cet article propose une révision taxonomique de Melanoxerus Kainul. & Bremer (Rubiaceae), un genre d’arbres à feuilles caduques avec des fleurs et des fruits attrayants qui est endémique de Madagascar. La description de trois nouvelles espèces, Melanoxerus antsirananensis Kainul., Melanoxerus atropurpureus Kainul. et Melanoxerus maritimus Kainul. est présentée accompagné de cartes de répartition et d’une clé d’identification des espèces. -

Expanded PDF Profile

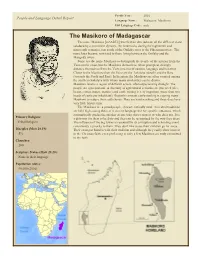

Profile Year: 2001 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: Malagasy, Masikoro ISO Language Code: msh The Masikoro of Madagascar The name Masikoro [mASikUr] was first used to indicate all the different clans subdued by a prominent dynasty, the Andrevola, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, just south of the Onilahy river to the Fiherenana river. The name later became restricted to those living between the Onilahy and the Mangoky rivers. Some use the name Masikoro to distinguish the people of the interior from the Vezo on the coast, but the Masikoro themselves, when prompted, strongly distance themselves from the Vezo in terms of custom, language and behavior. Closer to the Masikoro than the Vezo are the Tañalaña (South) and the Bara (towards the North and East). In literature the Masikoro are often counted among the southern Sakalava with whom many similarities can be drawn. Masikoro land is a region of difficult access, often experiencing drought. The people are agro-pastoral. A diversity of agricultural activities are practiced (rice, beans, cotton, maize, manioc) and cattle raising is very important (more than two heads of cattle per inhabitant). Recently rampant cattle-rustling is causing many Masikoro to reduce their cattle herds. They are hard-working and these days have very little leisure time. The Masikoro are a proud people, characteristically rural. Ancestral traditions are held high among them as is correct language use for specific situations, which automatically grades the speaker as one who shows respect or who does not. It is Primary Religion: a dishonor for them to be dirty and they can be recognized by the way they dress. -

Lesson 2 the People of Madagascar

LUTHERAN HOUR MINISTRIES online mission trip Curriculum LESSON 2 THE PEOPLE OF MADAGASCAR 660 MASON RIDGE CENTER DRIVE, SAINT LOUIS, MO 63141 | LHM.ORG 0117 LHM – MADAGASCAR Lesson 2 – The People of Madagascar Population On the map, Madagascar is very close to the eastern edge of Africa. This closeness would lead people to conclude that the inhabitants of Madagascar are predominately African. This is not true. The native inhabitants of Madagascar are the Malagasy (pronounced mah-lah-GAH-shee), who originated in Malaysia and Indonesia and reached Madagascar about 1,500 years ago. The language, customs, and physical appearance of today’s Malagasy reflect their Asian ancestry. Nearly 22.5 million people live in modern Madagascar. The annual growth rate of three percent combined with an average life expectancy of only sixty- four years gives Madagascar a young population. About sixty percent of the Malagasy people are less than twenty-five years old. Thirty-five percent of the adult population is classified as illiterate. More than ninety-five percent of the population is of Malagasy origin. The other five percent is made up of French, Comorians, Indo-Pakistanis, and Chinese peoples. The Malagasy are divided into 20 distinct ethnic groups, each of which occupies a certain area of the island. These groups originally started as loosely organized clans. Each clan remained apart from each other clan, marrying only within its clan. The clans developed into separate ethnic groups. Today there is an increased amount of intermarriage between the clans blurring the lines of distinction. All groups consider themselves as equally Malagasy. -

A Strategy to Reach Animistic People in Madagascar

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2006 A Strategy To Reach Animistic People in Madagascar Jacques Ratsimbason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Ratsimbason, Jacques, "A Strategy To Reach Animistic People in Madagascar" (2006). Dissertation Projects DMin. 690. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/690 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A STRATEGY TO REACH ANIMISTIC PEOPLE IN MADAGASCAR by Jacques Ratsimbason Adviser: Bruce Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A STRATEGY TO REACH ANIMISTIC PEOPLE IN MADAGASCAR Name of researcher: Jacques Ratsimbason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce Bauer, D.Miss. Date completed: August 2006 Problem The majority of the Malagasy people who live in Madagascar are unreached with the gospel message. A preliminary investigation of current literature indicated that 50 percent of the Malagasy are followers of traditional religions. This present study was to develop a strategy to reach the animistic people with the gospel message. Method This study presents Malagasy people, their social characteristics, population, worldviews, and lifestyles. A study;and evaluation of Malagasy beliefs and practices were developed using Hiebert's model of critical contextualization. Results The study reveals that the Seventh-day Adventist Church must update its evangelistic methods to reach animistic people and finish the gospel commission in Madagascar. -

An Exploration of the Relationship Between the Environment and Mahafaly Oral Literature

Environment as Social and Literary Constructs: An Exploration of the Relationship between the Environment and Mahafaly Oral Literature * Eugenie Cha 4 May 2007 Project Advisor: Jeanine Rambeloson Location: Ampanihy Program: Madagascar: Culture and Society Term: Spring semester 2007 Program Director: Roland Pritchett Acknowledgements This research would not have been possible without the wonderful assistance and support of those involved. First and foremost, many thanks to Gabriel Rahasimanana, my translator and fellow colleague who accompanied me to Ampanihy; thank you to my advisor, Professor Jeanine Rambeloson and to Professor Manassé Esoavelomandroso of the University of Tana; the Rahaniraka family in Toliara; Professors Barthelemy Manjakahery, Pietro Lupo, Aurélien de Moussa Behavira, and Jean Piso of the University of Toliara; Marie Razanonoro and José Austin; the Rakatolomalala family in Tana for their undying support and graciousness throughout the semester; and to Roland Pritchett for ensuring that this project got on its way. 2 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………4-6 History of Oral Literature in Madagascar…………………………………………......6-8 What is Oral Tradition………………………………………………………………..8-10 The Influence of Linguistic and Ethnic Diversity……………………………….......10-13 Location……………………………………………………………………………...13-14 Methodology………………………………………………………………………...14-17 Findings: How Ampanihy Came to Be………………………………………………17-18 “The Source of Life” and the Sacredness of Nature…………………………………18-21 Mahafaly Stories: Present-day Literature……………………………………….......21-29 1. Etsimangafalahy and Tsimagnolobala………………………………………23 2. The Three Kings………………………………………………………....23-26 3. The Baobab…………………………………………………………….........27 4. The Origins of the Mahafaly and Antandroy…………………………....27-28 5. Mandikalily……………………………………………………………...28-29 Modernization and Oral Literature: Developments and Dilemmas………………....29-33 Synthesis: Analysis of Findings…………………………………………………….33-36 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………...36-38 Appendix………………………………………………………………………………..39 A. -

Liste Candidatures Maires Atsimo Andrefana

NOMBRE DISTRICT COMMUNE ENTITE NOM ET PRENOM(S) CANDIDATS CANDIDATS ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 VAKISOA (ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA) AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 INDEPENDANT SOLO (INDEPENDANT SOLO) BESADA AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 AVI (ASA VITA NO IFAMPITSARANA) TOVONDRAOKE AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 TIM (TIAKO I MADAGASIKARA) REMAMORITSY AMPANIHY OUEST AMBOROPOTSY 1 HIARAKA ISIKA (HIARAKA ISIKA) SORODO INDEPENDANT MOSA Jean Baptiste (INDEPENDANT AMPANIHY OUEST AMPANIHY CENTRE 1 FOTOTSANAKE MOSA Jean Baptiste) ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST AMPANIHY CENTRE 1 TOVONASY (ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA) ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 ESOLONDRAY Raymond (ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA) AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 TIM (TIAKO I MADAGASIKARA) LAHIVANOSON Jacques AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 MMM (MALAGASY MIARA MIAINGA) KOLOAVISOA René INDEPENDANT TSY MIHAMBO RIE (INDEPENDANT AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 EMANINTSINDRAZA TSY MIHAMBO RIE) INDEPENDANT ESOATEHY Victor (INDEPENDANT AMPANIHY OUEST ANDROKA 1 EFANOMBO ESOATEHY Victor) ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST ANKILIABO 1 ZOENDRAZA Fanilina (ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA) INDEPENDANT TAHIENANDRO (INDEPENDANT AMPANIHY OUEST ANKILIABO 1 EMAZINY Mana TAHIENANDRO) AMPANIHY OUEST ANKILIABO 1 TIM (TIAKO I MADAGASIKARA) RASOBY AMPANIHY OUEST ANKILIABO 1 HIARAKA ISIKA (HIARAKA ISIKA) MAHATALAKE ISIKA REHETRA MIARAKA @ ANDRY RAJOELINA AMPANIHY OUEST -

Bulletin De Situation Acridienne Madagascar

BULLETIN DE SITUATION ACRIDIENNE MADAGASCAR Bulletin N°16 Juin 2014 SOMMAIRE CELLULE DE VEILLE ACRIDIENNE Situation générale: page 1 Situation éco-météorologique: page 2 Situation acridienne: page 3 Situation agro-socio-économique: page Situation antiacridienne: page Annexes: page SITUATION GÉNÉRALE En juin 2014, l’installation de la saison sèche et fraîche se confirmait dans l'ensemble du pays. Les strates herbeuses devenaient de plus en plus sèches en raison de l’insuffisance des réserves hydriques des sols des biotopes xérophiles et mésophiles. Dans l'Aire grégarigène, les populations diffuses entamaient leur regroupement dans les biotopes hygrophiles ; l'humidité édaphique permettant le maintien d'une végétation verte. Dans les régions prospectées, le taux de verdissement des strates herbeuses variait de 10 à 40 %. Des essaims de taille petite à moyenne ont été observés dans les compartiments Centre et Nord de l’Aire grégarigène et de l’Aire d’invasion. Des taches et bandes larvaires ont également été observées dans le compartiment Centre de l’Aire grégarigène. Les larves étaient de stade L2 à L5 et de phase transiens à grégaire. Les essaims étaient composés d’ailés immatures grégaires. Cependant, des traitements intenses effectués au cours de ce mois ont permis de diminuer les effectifs des populations acridiennes groupées. Du 1er au 30 juin 2014, 39 866 ha ont été identifiés comme infestés et 38 870 ha ont été traités ou protégés. Le traitement des superficies infestées restantes est programmé pour le mois prochain (annexe 1). Depuis le début de la campagne 2013/2014 et jusqu’au 30 juin 2014, 1 204 660 ha ont été traités ou protégés. -

Reglementation De La Filiere Bois Energie Dans La Region

EN PARTENARIAT AVEC : SEPTEMBRE REGLEMENTATION DE LA FILIERE BOIS ENERGIE DANS LA REGION ATSIMO ANDREFANA Acquis et leçons apprises • 2008 à 2011 Programme WWF à Madagascar et dans l’Océan Indien Occidental RÉSUMÉ Le bois est la principale source d’énergie utilisée par les ménages malgaches. Il représente 92% de l’offre énergétique à Madagascar. Le bois énergie, notamment le bois de chauffe et le charbon de bois, a l’avantage d’être disponible, facile à stocker et à utiliser, à faible coût par rapport à d’autres sources d’énergie de cuisson comme le gaz ou l’électricité. Les récentes analyses1 menées au niveau national prévoient une pénurie dans les années à venir si aucune mesure n’est prise, du fait d’une offre en bois énergie qui n’arrivera pas à satisfaire la demande. Par ailleurs, la répartition des ressources forestières disponibles n’est pas équilibrée. Les zones forestières à proximité des grandes villes sont sous forte pression pour satisfaire les besoins urbains en charbon de bois. La mise en place d’outils de régulation pour garantir l’approvisionnement durable en charbon de bois des milieux urbains s’avère ainsi nécessaire. Une proposition de réforme de textes législatifs régissant les activités de la filière a été proposée en 2009 à l’administration forestière, mais reste sans suite à ce jour. Ce projet de réforme avait fait Depuis 2008, le Programme du WWF à Madagascar et dans l’Océan Indien Occidental œuvre avec les différents acteurs de l’objet de différentes consultations, notamment au niveau des différentes directions interrégionales des forêts, pour la filière Bois Energie pour l’instauration d’une réglementation de la filière dans la région Atsimo Andrefana.