Eric Jacolliot Acted As Much More Than a Witness To, Or Cartographer Of, the Comings and Goings That Constitute This Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catherine Malabou's Plasticity in Translation

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 20:02 TTR Traduction, terminologie, rédaction Catherine Malabou’s Plasticity in Translation Le concept de plasticité chez Catherine Malabou, appliqué à la traduction Carolyn Shread Du système en traduction : approches critiques Résumé de l'article On Systems in Translation: Critical Approaches En traduisant La plasticité au soir de l’écriture. Dialectique, destruction, Volume 24, numéro 1, 1er semestre 2011 déconstruction (2005) de Catherine Malabou en vue de l’édition anglaise de 2009, j’ai été frappée de constater à quel point son concept de plasticité pouvait URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013257ar être utile pour repenser les notions conventionnelles en traduction. Dans cette DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1013257ar autobiographie philosophique, qui décrit ses rencontres avec Hegel, Heidegger, et Derrida, Malabou introduit « la plasticité » en suggérant que cette notion, plus contemporaine, pourrait remplacer la conception d’écriture comme Aller au sommaire du numéro schème moteur de Derrida. Après avoir revu et explicité les réflexions innovatrices de Derrida sur la traduction, j’avance que les pouvoirs de donner, de recevoir, d’exploser et de régénérer la forme qui sont décrits par la Éditeur(s) plasticité modifient la modification et altèrent ainsi la transformation qu’est la traduction. Pour adapter le concept philosophique de Malabou à la Association canadienne de traductologie traductologie, j’établis une distinction entre la traduction élastique et la traduction plastique, ce qui me permet de faire voler en éclats les paradigmes ISSN d’équivalence, qui depuis si longtemps restreignent la théorie et la pratique de 0835-8443 (imprimé) la traduction. -

The Unlimited Responsibility of Spilling Ink Marko Zlomislic

ISSN 1393-614X Minerva - An Internet Journal of Philosophy 11 (2007): 128-152 ____________________________________________________ The Unlimited Responsibility of Spilling Ink Marko Zlomislic Abstract In order to show that both Derrida’s epistemology and his ethics can be understood in terms of his logic of writing and giving, I consider his conversation with Searle in Limited Inc. I bring out how a deconstruction that is implied by the dissemination of writing and giving makes a difference that accounts for the creative and responsible decisions that undecidability makes possible. Limited Inc has four parts and I will interpret it in terms of the four main concepts of Derrida. I will relate signature, event, context to Derrida’s notion of dissemination and show how he differs from Austin and Searle concerning the notion of the signature of the one who writes and gives. Next, I will show how in his reply to Derrida, entitled, “Reiterating the Differences”, Searle overlooks Derrida’s thought about the communication of intended meaning that has to do with Derrida’s distinction between force and meaning and his notion of differance. Here I will show that Searle cannot even follow his own criteria for doing philosophy. Then by looking at Limited Inc, I show how Derrida differs from Searle because repeatability is alterability. Derrida has an ethical intent all along to show that it is the ethos of alterity that is called forth by responsibility and accounted for by dissemination and difference. Of course, comments on comments, criticisms of criticisms, are subject to the law of diminishing fleas, but I think there are here some misconceptions still to be cleared up, some of which seem to still be prevalent in generally sensible quarters. -

Catherine Malabou's Plasticity in Translation

Document generated on 10/03/2021 12:25 p.m. TTR Traduction, terminologie, rédaction Catherine Malabou’s Plasticity in Translation Le concept de plasticité chez Catherine Malabou, appliqué à la traduction Carolyn Shread Du système en traduction : approches critiques Article abstract On Systems in Translation: Critical Approaches Translating Catherine Malabou’s La Plasticité au soir de l’écriture: Dialectique, Volume 24, Number 1, 1er semestre 2011 destruction, déconstruction (2005) for its 2009 English publication, I was struck by how suggestive Malabou’s concept of plasticity is for a reworking of URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013257ar conventional notions of translation. In this philosophical autobiography of her DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1013257ar encounters with Hegel, Heidegger, and Derrida, Malabou introduces “plasticity,” suggesting that the more contemporary notion of plasticity supersede Derrida’s proposal of writing as motor scheme. Reviewing and See table of contents developing Derrida’s innovative discussions of translation, this article argues that the giving, receiving, exploding, and regenerating of form described by plasticity changes change, and therefore alters the transformation that is Publisher(s) translation. Adapting Malabou’s philosophical concept to the field of translation studies, I make a distinction between elastic translation and plastic Association canadienne de traductologie translation, which allows us to break free of paradigms of equivalence that have for so long constrained translation theories and practice. While plasticity ISSN drives Malabou’s philosophical intervention in relation to identity and gender, 0835-8443 (print) it also enables a productive reconceptualization of translation, one which not 1708-2188 (digital) only privileges seriality and generativity over narratives of nostalgia for a lost original, but which also forges connections across different identity discourses on translation. -

A Conversation with Catherine Malabou

CATHERINE MALABOU University of Paris X-Nanterre NOËLLE VAHANIAN Lebanon Valley College A CONVERSATION WITH CATHERINE MALABOU he questions of the following interview are aimed at introducing Catherine Malabou’s work and philosophical perspective to an audience who may T have never heard of her, or who knows only that she was a student of Derrida. What I hope that this interview reveals, however, is that Malabou “follows” deconstruction in a timely, and also useful way. For one of the common charges levied against deconstruction, at least by American critics, is that by opening texts to infinite interpretations, deconstruction unfortunately does away with more than the master narratives; it mires political agency in identity politics and offers no way out the socio-historical and political constructs of textuality other than the hope anchored in faith at best, but otherwise simply in the will to believe that the stance of openness to the other will let the other become part of the major discourses without thereby marginalizing or homogenizing them. How does Malabou “follow” deconstruction? Indeed, she does not disavow her affiliation with Derrida; she, too, readily acknowledges that there is nothing outside the text. But, by the same token, she also affirms Hegel’s deep influence on her philosophy. From Hegel, she borrows the central concept of her philosophy, namely, the concept of plasticity; the subject is plastic—not elastic, it never springs back into its original form—it is malleable, but it can explode and create itself anew. In this way, there is nothing outside the text, but the text is no less natural than it is cultural, it is no less biological than it is spiritual (or mental), it is no less material than it is historical. -

'Little Terrors'

Don DeLillo’s Promiscuous Fictions: The Adulterous Triangle of Sex, Space, and Language Diana Marie Jenkins A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of English University of NSW, December 2005 This thesis is dedicated to the loving memory of a wonderful grandfather, and a beautiful niece. I wish they were here to see me finish what both saw me start. Contents Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 2 Chapter One 26 The Space of the Hotel/Motel Room Chapter Two 81 Described Space and Sexual Transgression Chapter Three 124 The Reciprocal Space of the Journey and the Image Chapter Four 171 The Space of the Secret Conclusion 232 Reference List 238 Abstract This thesis takes up J. G. Ballard’s contention, that ‘the act of intercourse is now always a model for something else,’ to show that Don DeLillo uses a particular sexual, cultural economy of adultery, understood in its many loaded cultural and literary contexts, as a model for semantic reproduction. I contend that DeLillo’s fiction evinces a promiscuous model of language that structurally reflects the myth of the adulterous triangle. The thesis makes a significant intervention into DeLillo scholarship by challenging Paul Maltby’s suggestion that DeLillo’s linguistic model is Romantic and pure. My analysis of the narrative operations of adultery in his work reveals the alternative promiscuous model. I discuss ten DeLillo novels and one play – Americana, Players, The Names, White Noise, Libra, Mao II, Underworld, the play Valparaiso, The Body Artist, Cosmopolis, and the pseudonymous Amazons – that feature adultery narratives. -

"One Nation •¦ Indivisible": Jacques Derrida on the Autoimmunity

RP 36_f4_12-44 11/13/06 11:56 AM Page 15 “ONE NATION . INDIVISIBLE”: JACQUES DERRIDA ON THE AUTOIMMUNITY OF DEMOCRACY AND THE SOVEREIGNTY OF GOD by MICHAEL NAAS DePaul University ABSTRACT During the final decade of his life, Jacques Derrida came to use the trope of autoimmunity with greater and greater frequency. Indeed it today appears that autoimmunity was to have been the last iteration of what for more than forty years Derrida called decon- struction. This essay looks at the consequences of this terminological shift for our under- standing not only of Derrida’s final works (such as Rogues) but of his entire corpus. By taking up a term from the biological sciences that describes the process by which an organism turns in quasi-suicidal fashion against its own self-protection, Derrida was able to rethink the very notion of life otherwise and demonstrate the way in which every sovereign identity, from the self to the nation-state to, most provocatively, God, is open to a process that both threatens to destroy it and gives it its only chance of living on. 1. Pledge of Allegiance I In a volume of remembrance, a volume “in memory of Jacques Derrida,” it is perhaps not inappropriate to begin with a personal memory, even if it might initially appear to have little to do with Derrida.1 It is an old memory, a quintessentially American memory, and one that I suspect many readers of this journal may share. It is the memory of a speech act, a sort of originary profession of faith, the memory of a pledge that I, like most other American school children, recited by heart, that is, in my case, thoughtlessly, mechani- cally, irresponsibly, with the regularity of a tape recording played back in an endless loop, at the beginning of every single school day. -

Derrida in the University, Or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction / C

Derrida in the University, or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction / C. Kelly 49 CSSHE SCÉES Canadian Journal of Higher Education Revue canadienne d’enseignement supérieur Volume 42, No. 2, 2012, pages 49-66 Derrida in the University, or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction Colm Kelly St. Thomas University ABSTRACT Derrida’s account of Kant’s and Schelling’s writings on the origins of the mod- ern university are interpreted to show that theoretical positions attempting to oversee and master the contemporary university find themselves destabilized or deconstructed. Two examples of contemporary attempts to install the lib- eral arts as the guardians and overseers of the contemporary university are examined. Both examples fall prey to the types of deconstructive displace- ments identified by Derrida. The very different reasoning behind Derrida’s own institutional intervention in the modern French university is discussed. This discussion leads to concluding comments on the need to defend pure re- search in the humanities, as well as in the social and natural sciences, rather than elevating the classical liberal arts to a privileged position. RÉSUMÉ Le compte-rendu de Derrida sur les écrits de Kant et de Schelling portant sur les origines de l’université moderne démontre que des positions théoriques tentant de surveiller et de gouverner l’université contemporaine se trouvent déstabilisées et déconstruites. L’auteur étudie deux exemples de tentatives contemporaines visant à donner aux arts libéraux le statut de gardiens et de surveillants de l’université contemporaine. Les deux exemples en question ne tiennent pas la route devant les substitutions déconstructives identifiées par Derrida. -

Expanded Academic ASAP - Document 8/21/13 1:27 PM

Expanded Academic ASAP - Document 8/21/13 1:27 PM Title: The rhetoric of drugs: an interview Author(s): Michael Israel Source: differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. 5.1 (Spring 1993): p1. Document Type: Interview Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1993 Duke University Press http://dukeupress.edu/ Full Text: Works Cited Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Trans. John Cumming. London: Verso, 1979. Artaud, Antonin. "Letter to the Legislator of the Drug Act." Collected Works of Antonin Artaud. Trans. Victor Conti. Vol. 1. London: Calder, 1968. 58-62. 4 vols. 1968-74. Baudelaire, Charles. "Les Paradis artificiels." Oeuvres completes. Ed. Claude Pichois. Vol. 2. Paris: Gallimard, 1975. The following interview originally appeared in a special issue of Autrement 106 (1989) edited by J.-M. Hervieu and then in the collection, Points de suspension: Entretiens (Paris: Galilee, 1992). Michael Israel's translation was first published in 1-800 2 (1991). Eds. When the sky of transcendence comes to be emptied, a fatal rhetoric fills the void, and this is the fetishism of drug addiction. A: You are not a specialist in the study of drug addiction, yet we suppose that as a philosopher you may have something of particular interest to say on this subject. At the very least, we assume that your thinking might be pertinent here, if only by way of those concepts common both to philosophy and addictive studies, for example dependency, liberty, pleasure, jouissance. JD: O.K. Let us speak then from the point of view of the non-specialist which indeed I am. -

A Journal of Feminist Philosophy

HYPATIA A JOURNAL OF FEMINIST PHILOSOPHY VOLUME 35 NUMBER 4 FALL 2020 Editorial Team (Co-Editors) Editors Emeritae Bonnie Mann, University of Oregon Ann Garry (Co-Editor 2017-2018) Erin McKenna, University of Oregon California State University, Los Angeles Camisha Russel, University of Oregon Serene J. Khader (Co-Editor 2017-2018) Rocio Zambrana, Emory University Brooklyn College and CUNY Graduate Center Hypatia Reviews Online Editors Alison Stone (Co-Editor 2017-2018) Clara Fisher, University College, Dublin Lancaster University Erin McKenna, University of Oregon Sally Scholz (Editor 2013-2017) Villanova University Managing Editors Ann Cudd (Co-Editor 2010-2013) Sarah LaChance Adams, University of North Boston University Florida (Hypatia) Caroline R. Lundquist, University of Oregon Linda Martín Alcoff (Co-Editor 2010-2013) (Hypatia) Hunter College, CUNY Graduate Center Bjørn Kristensen, University of Oregon Alison Wylie (Co-Editor 2008-2013) (Hypatia Reviews Online) University of British Columbia Lori Gruen (Co-Editor 2008-2010) Social Media Editor/ Wesleyan University Managing Editor Assistant Brooke Burns, University of Oregon Hilde Lindemann (Editor 2003-2008) Michigan State University Associate Editors Laurie Shrage (Co-Editor 1998-2003) Maria del Rosario Acosta-López, University of California State Polytechnic University California-Riverside Nancy Tuana (Co-Editor 1998-2003) Saray Ayala-López, California State University- Pennsylvania State University Sacramento Talia Mae Bettcher, University of California- Cheryl Hall (Co-Editor 1995-1998) Los Angeles University of South Florida Ann Cudd, University of Pittsburgh Joanne Waugh (Co-Editor 1995-1998) Vrinda Dalmiya, University of Hawaii-Manoa University of South Florida Verónica Gago, Universidad de Buenos Aires/ Linda López McAlister (Editor 1990-1995, Universidad Nacional de San Martín Co-Editor 1995-1998) Dilek Huseyinzadegan, Emory University University of South Florida Qrescent Mali Mason, Haverford College Krushil Watene, Massey University Margaret A. -

The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder Morgan Carter Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones Professional Writing Spring 4-24-2019 The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder Morgan Carter Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mapw_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Morgan, "The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder" (2019). Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones. 48. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mapw_etd/48 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Professional Writing at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder By Morgan Carter A capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Writing in the Department of English In the College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia 2019 Contents Introduction 1 Literature Review 4 Chapter One: Narrative 15 Chapter Two: Critique 30 Chapter Three: Conclusion 45 Works Cited 49 iii For those who are still sick and suffering and for the kids caught in the cross-fire Introduction The addict and alcoholic are members of society who are continuously marginalized by the language used to describe them, both by media coverage and everyday language. The nature of their disease creates a space of self-identification that is outside the norm of normal illness. -

Jacques Derrida Law As Absolute Hospitality

JACQUES DERRIDA LAW AS ABSOLUTE HOSPITALITY JACQUES DE VILLE NOMIKOI CRITICAL LEGAL THINKERS Jacques Derrida Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality presents a comprehensive account and understanding of Derrida’s approach to law and justice. Through a detailed reading of Derrida’s texts, Jacques de Ville contends that it is only by way of Derrida’s deconstruction of the metaphysics of presence, and specifi cally in relation to the texts of Husserl, Levinas, Freud and Heidegger, that the reasoning behind his elusive works on law and justice can be grasped. Through detailed readings of texts such as ‘To Speculate – on Freud’, Adieu, ‘Declarations of Independence’, ‘Before the Law’, ‘Cogito and the History of Madness’, Given Time, ‘Force of Law’ and Specters of Marx, de Ville contends that there is a continuity in Derrida’s thinking, and rejects the idea of an ‘ethical turn’. Derrida is shown to be neither a postmodernist nor a political liberal, but a radical revolutionary. De Ville also controversially contends that justice in Derrida’s thinking must be radically distinguished from Levinas’s refl ections on ‘the Other’. It is the notion of absolute hospitality – which Derrida derives from Levinas, but radically transforms – that provides the basis of this argument. Justice must, on de Ville’s reading, be understood in terms of a demand of absolute hospitality which is imposed on both the individual and the collective subject. A much needed account of Derrida’s infl uential approach to law, Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality will be an invaluable resource for those with an interest in legal theory, and for those with an interest in the ethics and politics of deconstruction. -

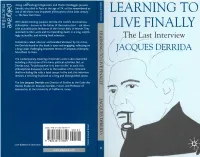

Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally the Last Interview

ZJ ~T~} 'Along with Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger, Jacques Q, Qj Derrida, who died in Paris at the age of 74, will be remembered as —— one of the three most important philosophers of the 20th century.' LEARNING TO >*J — The New York Times r— ^-» With death looming, Jacques Derrida, the world's most famous __ *T\ philosopher - known as the father of 'deconstruction' - sat down ~' with journalist Jean Birnbaum of the French daily Le Monde. They LIVE FINALLY revisited his life's work and his impending death in a long, surpris• ingly accessible, and moving final interview. The Last Interview Sometimes called 'obscure' and branded 'abstruse' by his critics, the Derrida found in this book is open and engaging, reflecting on a long career challenging important tenets of European philosophy 'ACOUES DERRIDA from Plato to Marx. The contemporary meaning of Derrida's work is also examined, including a discussion of his many political activities. But, as Derrida says, 'To philosophize is to learn to die'; as such, this philosophical discussion turns to the realities of his imminent death-including life with a fatal cancer. In the end, this interview remains a touching final look at a long and distinguished career. The late Jacques Derrida was Director of Studies at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, France, and Professor of Humanities at the University of California, Irvine. ISBN 978-0-230-53785-9 9 780230 537859 Cover illustration © Carol Hayes Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally The Last Interview Jacques Derrida An Interview with Jean Birnbaum Translated by Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas With a bibliography by Peter Krapp All rights reserved.