The Place of Consignation, Or Memory and Writing in Derrida's Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negative: on the Translation of Jacques Derrida, Mal D'archive

Negative: On the Translation of Jacques Derrida, Mal d’Archive Daniel James Barker Actually it has been written twice... I determined to give it up; but it tormented me like an unlaid ghost.1 Yes, I am teaching something positive here. Ex- cept that it is expressed by a negation. But why shouldn’t it be as positive as anything else?2 There is no meta-archive.3 COLLOQUY text theory critique 19 (2010). © Monash University. www.colloquy.monash.edu.au/issue19/barker.pdf 6 Daniel James Barker ░ Argument This paper will follow the thread that may be traced in Derrida’s Mal d’Archive4 when the title is translated as “The Archive Bug.” In so doing, it will attempt to describe the ways in which the death drive as it appears in Mal d’Archive may be related to the (non-)concept of différance as it has emerged in Derrida’s theoretical writings under various names. The argument will hinge on the thinking of différance as a virus, in the sense of an (anti-)information (non-)entity which propagates by entering a genetic structure and substituting elements of its code. Entstellung [Re-Framing] ... and I always dream of a pen that would be a syringe, a suction point rather than that very hard weapon with which one must in- scribe, incise, choose, calculate, take ink before filtering the inscrib- able, playing the keyboard on the screen, whereas here, once the right vein has been found, no more toil, no responsibility, no risk of bad taste nor of violence, the blood delivers itself alone, the inside gives itself up and you can do as you like with it ...5 Nevertheless, the needle must puncture the skin: a small violence. -

Derrida's Open and Its Closure: the Aporia of Différance and the Only

Language, Literature, and Interdisciplinary Studies (LLIDS) ISSN: 2547-0044 http://ellids.com/archives/2018/09/2.1-Wu.pdf CC Attribution-No Derivatives 4.0 International License www.ellids.com Derrida’s Open and Its Closure: The Aporia of Différance and the Only Logic of Thinking Mengxue Wu “…for an opening is relative to a ‘surrounding plenitude.’”1 “The gallery is the labyrinth which includes in itself its own exits: we have never come upon it as upon a particular case of experience—that which Husserl believes he is describing.”2 Metaphysics—the entire history of metaphysics has been considered as the metaphysics of presence—is closed; it is closed like a dead end. In its “surrounding plenitude” no exit can be found and it is meeting its own death. Though a system of philosophy with incompleteness is not a perfect theory, but the rebuke of how comprehensive and close a philosophy is and the demand of that philosophy to open its house to the alien and the ungraspable would be a preposterous importunity. However, upon the stage where the entire history of Western philosophy has been played, “…nothing is staged or displayed theatrically. Rather, the battle of the new gods against the old is being fought” (Heidegger 22). This battle, between the new gods and the old, between the new thoughts and the old, is a battle of breaking into new ruptures and finding new openings in the old thoughts. At the moment when traditional philosophy has become a closure of the metaphysics of presence, even those streams of thought that already broke new phenomenological grounds in the beginning of twentieth century and Levinas’s ethical breaking are closed “as the self-presence in absolute knowledge” (Derrida 102, SP). -

Derridas Writing and Difference: a Readers Guide Free

FREE DERRIDAS WRITING AND DIFFERENCE: A READERS GUIDE PDF Sarah Wood | 192 pages | 08 Jul 2009 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780826491923 | English | London, United Kingdom Writing and Difference by Jacques Derrida Philosophy: General Philosophy. You may purchase this title at these fine bookstores. Outside the USA, see our international sales information. University of Chicago Press: E. About Contact News Giving to the Press. Cultural Graphology Juliet Fleming. Dissemination Jacques Derrida. Given Time Jacques Derrida. Writing and Difference Jacques Derrida. Jacques Derrida Translated by Alan Bass. In it we find Derrida at work on his systematic deconstruction of Western metaphysics. In these essays, Derrida demonstrates the traditional nature of some purportedly nontraditional currents of modern thought—one of his main targets being the way in which "structuralism" unwittingly repeats metaphysical concepts in its use of linguistic models. Writing and Difference reveals the unacknowledged program Derridas Writing and Difference: A Readers Guide makes thought itself possible. In analyzing the contradictions inherent in this program, Derrida foes on to develop new ways of thinking, reading, and writing,—new ways based on the most complete and rigorous understanding of the old ways. Scholars and Derridas Writing and Difference: A Readers Guide from all disciplines will find Writing and Difference an excellent introduction to perhaps the most challenging of contemporary French thinkers—challenging because Derrida questions thought as we know it. Table of Contents. Force and Signification 2. Cogito and the History of Madness 3. Freud and the Scene of Writing 8. The Theater of Cruelty and the Closure of Representation 9. Ellipsis Notes Sources. Chicago Blog : Philosophy. -

'Little Terrors'

Don DeLillo’s Promiscuous Fictions: The Adulterous Triangle of Sex, Space, and Language Diana Marie Jenkins A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of English University of NSW, December 2005 This thesis is dedicated to the loving memory of a wonderful grandfather, and a beautiful niece. I wish they were here to see me finish what both saw me start. Contents Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 2 Chapter One 26 The Space of the Hotel/Motel Room Chapter Two 81 Described Space and Sexual Transgression Chapter Three 124 The Reciprocal Space of the Journey and the Image Chapter Four 171 The Space of the Secret Conclusion 232 Reference List 238 Abstract This thesis takes up J. G. Ballard’s contention, that ‘the act of intercourse is now always a model for something else,’ to show that Don DeLillo uses a particular sexual, cultural economy of adultery, understood in its many loaded cultural and literary contexts, as a model for semantic reproduction. I contend that DeLillo’s fiction evinces a promiscuous model of language that structurally reflects the myth of the adulterous triangle. The thesis makes a significant intervention into DeLillo scholarship by challenging Paul Maltby’s suggestion that DeLillo’s linguistic model is Romantic and pure. My analysis of the narrative operations of adultery in his work reveals the alternative promiscuous model. I discuss ten DeLillo novels and one play – Americana, Players, The Names, White Noise, Libra, Mao II, Underworld, the play Valparaiso, The Body Artist, Cosmopolis, and the pseudonymous Amazons – that feature adultery narratives. -

"One Nation •¦ Indivisible": Jacques Derrida on the Autoimmunity

RP 36_f4_12-44 11/13/06 11:56 AM Page 15 “ONE NATION . INDIVISIBLE”: JACQUES DERRIDA ON THE AUTOIMMUNITY OF DEMOCRACY AND THE SOVEREIGNTY OF GOD by MICHAEL NAAS DePaul University ABSTRACT During the final decade of his life, Jacques Derrida came to use the trope of autoimmunity with greater and greater frequency. Indeed it today appears that autoimmunity was to have been the last iteration of what for more than forty years Derrida called decon- struction. This essay looks at the consequences of this terminological shift for our under- standing not only of Derrida’s final works (such as Rogues) but of his entire corpus. By taking up a term from the biological sciences that describes the process by which an organism turns in quasi-suicidal fashion against its own self-protection, Derrida was able to rethink the very notion of life otherwise and demonstrate the way in which every sovereign identity, from the self to the nation-state to, most provocatively, God, is open to a process that both threatens to destroy it and gives it its only chance of living on. 1. Pledge of Allegiance I In a volume of remembrance, a volume “in memory of Jacques Derrida,” it is perhaps not inappropriate to begin with a personal memory, even if it might initially appear to have little to do with Derrida.1 It is an old memory, a quintessentially American memory, and one that I suspect many readers of this journal may share. It is the memory of a speech act, a sort of originary profession of faith, the memory of a pledge that I, like most other American school children, recited by heart, that is, in my case, thoughtlessly, mechani- cally, irresponsibly, with the regularity of a tape recording played back in an endless loop, at the beginning of every single school day. -

Education As the Possibility of Justice: Jacques Derrida

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 422 198 SO 028 563 AUTHOR Biesta, Gert J. J. TITLE Education as the Possibility of Justice: Jacques Derrida. PUB DATE 1997-03-00 NOTE 35p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Chicago, IL, March 24-28, 1997). PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Educational Philosophy; *Educational Theories; Epistemology; Hermeneutics; Higher Education; *Justice; *Philosophy IDENTIFIERS *Derrida (Jacques); Poststructuralism ABSTRACT This paper is an analysis of the ongoing work of philosopher Jacques Derrida and the immense body of work associated with him. Derrida's copious work is difficult to categorize since Derrida challenges the very concept that meaning can be grasped in its original moment or that meaning can be represented in the form of some proper, self-identical concept. Derrida's "deconstruction" requires reading, writing, and translating Derrida, an impossibility the author maintains cannot be done because translation involves transformation and the originality of the original only comes into view after it has been translated. The sections of the paper include: (1) "Preface: Reading Derrida, Writing after Derrida"; (2) "Curriculum Vitae"; (3) "(No) Philosophy"; (4) "The Myth of the Origin"; (5) "The Presence of the Voice"; (6) "The Ubiquity of Writing"; (7) "Difference and 'Differance'"; (8) "Deconstruction and the Other"; (9) "Education"; (10) "Education beyond Representation: Gregory Ulmer's 'Post(e)-pedagogy"; and (11) "Afterword: Education as the Possibility of Justice." (EH) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ******************************************************************************** Education as the Possibility of Justice: Jacques Derrida. -

Expanded Academic ASAP - Document 8/21/13 1:27 PM

Expanded Academic ASAP - Document 8/21/13 1:27 PM Title: The rhetoric of drugs: an interview Author(s): Michael Israel Source: differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. 5.1 (Spring 1993): p1. Document Type: Interview Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1993 Duke University Press http://dukeupress.edu/ Full Text: Works Cited Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Trans. John Cumming. London: Verso, 1979. Artaud, Antonin. "Letter to the Legislator of the Drug Act." Collected Works of Antonin Artaud. Trans. Victor Conti. Vol. 1. London: Calder, 1968. 58-62. 4 vols. 1968-74. Baudelaire, Charles. "Les Paradis artificiels." Oeuvres completes. Ed. Claude Pichois. Vol. 2. Paris: Gallimard, 1975. The following interview originally appeared in a special issue of Autrement 106 (1989) edited by J.-M. Hervieu and then in the collection, Points de suspension: Entretiens (Paris: Galilee, 1992). Michael Israel's translation was first published in 1-800 2 (1991). Eds. When the sky of transcendence comes to be emptied, a fatal rhetoric fills the void, and this is the fetishism of drug addiction. A: You are not a specialist in the study of drug addiction, yet we suppose that as a philosopher you may have something of particular interest to say on this subject. At the very least, we assume that your thinking might be pertinent here, if only by way of those concepts common both to philosophy and addictive studies, for example dependency, liberty, pleasure, jouissance. JD: O.K. Let us speak then from the point of view of the non-specialist which indeed I am. -

Derridean Deconstruction and Feminism

DERRIDEAN DECONSTRUCTION AND FEMINISM: Exploring Aporias in Feminist Theory and Practice Pam Papadelos Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Gender, Work and Social Inquiry Adelaide University December 2006 Contents ABSTRACT..............................................................................................................III DECLARATION .....................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................V INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 THESIS STRUCTURE AND OVERVIEW......................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS – FEMINISM AND DECONSTRUCTION ............................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 8 FEMINIST CRITIQUES OF PHILOSOPHY..................................................................... 10 Is Philosophy Inherently Masculine? ................................................................ 11 The Discipline of Philosophy Does Not Acknowledge Feminist Theories......... 13 The Concept of a Feminist Philosopher is Contradictory Given the Basic Premises of Philosophy..................................................................................... -

The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder Morgan Carter Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones Professional Writing Spring 4-24-2019 The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder Morgan Carter Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mapw_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Morgan, "The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder" (2019). Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones. 48. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mapw_etd/48 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Professional Writing at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder By Morgan Carter A capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Writing in the Department of English In the College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia 2019 Contents Introduction 1 Literature Review 4 Chapter One: Narrative 15 Chapter Two: Critique 30 Chapter Three: Conclusion 45 Works Cited 49 iii For those who are still sick and suffering and for the kids caught in the cross-fire Introduction The addict and alcoholic are members of society who are continuously marginalized by the language used to describe them, both by media coverage and everyday language. The nature of their disease creates a space of self-identification that is outside the norm of normal illness. -

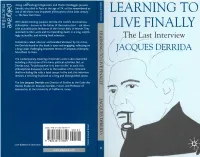

Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally the Last Interview

ZJ ~T~} 'Along with Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger, Jacques Q, Qj Derrida, who died in Paris at the age of 74, will be remembered as —— one of the three most important philosophers of the 20th century.' LEARNING TO >*J — The New York Times r— ^-» With death looming, Jacques Derrida, the world's most famous __ *T\ philosopher - known as the father of 'deconstruction' - sat down ~' with journalist Jean Birnbaum of the French daily Le Monde. They LIVE FINALLY revisited his life's work and his impending death in a long, surpris• ingly accessible, and moving final interview. The Last Interview Sometimes called 'obscure' and branded 'abstruse' by his critics, the Derrida found in this book is open and engaging, reflecting on a long career challenging important tenets of European philosophy 'ACOUES DERRIDA from Plato to Marx. The contemporary meaning of Derrida's work is also examined, including a discussion of his many political activities. But, as Derrida says, 'To philosophize is to learn to die'; as such, this philosophical discussion turns to the realities of his imminent death-including life with a fatal cancer. In the end, this interview remains a touching final look at a long and distinguished career. The late Jacques Derrida was Director of Studies at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, France, and Professor of Humanities at the University of California, Irvine. ISBN 978-0-230-53785-9 9 780230 537859 Cover illustration © Carol Hayes Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally The Last Interview Jacques Derrida An Interview with Jean Birnbaum Translated by Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas With a bibliography by Peter Krapp All rights reserved. -

Trauma and Psychoanalysis, Beyond Life and Death

SUFFERING AND SURVIVAL: CONSIDERING TRAUMA, TRAUMA STUDIES AND LIVING ON MARK DAWSON Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies September, 2010 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2010: The University of Leeds and Mark Dawson. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS What remains beyond this thesis are the others to whom it is indebted; though it is impossible to name them all, I would like to acknowledge the sustained and indispensable guidance of my supervisors, Dr. Ashley Thompson and Professor Griselda Pollock. I would also like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Barbara Engh and Dr. Rowan Bailey, as well as note the unique and stimulating environment of the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies at The University of Leeds. I would also like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for their financial assistance. I want especially to thank my mother, for her love as well as her unwavering support, and Sarah, for her love, belief, and the remarkable capacity to welcome the uncertainties of this process. ABSTRACT Referring to the academic phenomenon of ‗Trauma Studies‘, this thesis argues that if it is possible to ‗speak about and speak through‘ trauma (Caruth, 1996), such a double operation can only occur through a writing which, paradoxically, touches on what exceeds it. -

Jacques Derrida PDF Book

JACQUES DERRIDA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicholas Royle | 208 pages | 01 Jun 2003 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415229319 | English | London, United Kingdom Jacques Derrida PDF Book Derrida argues that intention cannot possibly govern how an iteration signifies, once it becomes hearable or readable. This danger explains why unconditional openness of the borders is not the best as opposed to what we were calling the worst above ; it is only the less bad or less evil, the less violence. Jacques Derrida. Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. The event that projected him into the international limelight was a conference at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in , where the relatively unknown but incontrovertibly glamorous young philosopher upstaged the likes of Lacan and Jean Hyppolite. Derrida insisted that a distinct political undertone had pervaded his texts from the very beginning of his career. Yet each of these concepts excludes the other. And this is what I confide in secret to whomever allies himself to me. For example, an image needs to be held by something, just as a mirror will hold a reflection. The giver cannot even recognise that they are giving, for that would be to reabsorb their gift to the other person as some kind of testimony to the worth of the self — ie. The intimacy of friendship, Derrida writes, lies in the sensation of recognizing oneself in the eyes of another. I deployed all my resources to uncover a range of meanings fanning out from each sentence, each word. These are, of course, themes reflected upon at length by Derrida, and they have an immediate consequence on the meta-theoretical level.