Environmental History, Ecocriticism and the Kentucky Cycle Theresa J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

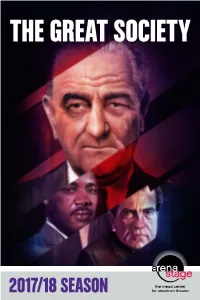

Play Guide for the Great Society

Written by Robert Schenkkan Directed by Ron Pel us o O cto ber 6 —2 8 , 2 0 1 8 P L AY G UI D E THE PLAY It is 1965 and President Lyndon Baines Johnson is at a critical point in his presidency. He is launching The Great Society, an ambitious set of social programs that would increase funds for health care, education and poverty. He also wants to pass the Voting Rights Act, an act that would secure voting rights for minority communities across the country. At each step, Johnson faces resistance. Conservatives like Senator Everett Dirksen are pushing for budget cuts on his social welfare programs. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, is losing patience at the lack of progress on voting rights. With rising discrimination against black communities in America, King takes matters into his own hands, organizing a civil rights protest in Selma, Alabama. Outside the U.S., the crisis in Vietnam is escalating. When the Viet Cong attacks a Marine support base, Johnson is faced with a difficult decision: should he deploy more American troops to fight overseas or should he focus on fighting the war on poverty within the U.S.? Time is ticking and the next presidential election is around the corner. In an America divided by civil rights protests and the anguish of Vietnam War, can Johnson pave the way for a great society? Page 2 MEET THE PLAYWIRGHT — ROBERT SCHENKKAN Robert Schenkkan was born in North Carolina and raised in Texas. He studied theater and discovered his passion for creating original worlds through playwrighting. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Great Society by Robert Schenkkan the Great Society

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Great Society by Robert Schenkkan The Great Society. Playwright Robert Schenkkan returns to the Great White Way with this second play, celebrating LBJ's presidential legacy. This new work accompanies Schenkkan’s Tony Award-winning All The Way , which saw Bryan Cranston win his first Tony for "Best Actor in a Leading Role in a Play" back in 2014 for his performance as the 1960s American president. All The Way played the Neil Simon Theatre from February 10 through June 29, 2014, taking home the Tony Award for “Best Play.” This production actually marks Schenkkan’s third Broadway outing as a playwright. In the fall of 1993, he made his Broadway debut as a writer with The Kentucky Cycle , which won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1992 and led to his first Tony Award nomination for “Best Play” in 1994. Taking the reins from Bryan Cranston and carrying the LBJ baton into The Great Society , Brian Cox is also no stranger to the Great White Way, of course. Having made his Broadway debut back in February 1985 in Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude , he has gone on to make waves in the theatre with his performances in Yasmina Reza’s Art in 1998, Tom Stoppard’s Rock ‘n’ Roll in 2007, and Jason Miller’s That Championship Season in 2011. A native of Dundee, Scotland, he also boasts a formidable résumé, when it comes to the UK stage. A two-time Olivier Award winner in his own right, he has worked extensively with the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre, alongside other esteemed establishments around the UK. -

In Kindergarten with the Author of WIT

re p resenting the american theatre DRAMATISTS by publishing and licensing the works PLAY SERVICE, INC. of new and established playwrights. atpIssuel 4,aFall 1999 y In Kindergarten with the Author of WIT aggie Edson — the celebrated playwright who is so far Off- Broadway, she’s below the Mason-Dixon line — is performing a Mdaily ritual known as Wiggle Down. " Tapping my toe, just tapping my toe" she sings, to the tune of "Singin' in the Rain," before a crowd of kindergarteners at a downtown elementary school in Atlanta. "What a glorious feeling, I'm — nodding my head!" The kids gleefully tap their toes and nod themselves silly as they sing along. "Give yourselves a standing O!" Ms. Edson cries, when the song ends. Her charges scramble to their feet and clap their hands, sending their arms arcing overhead in a giant "O." This willowy 37-year-old woman with tousled brown hair and a big grin couldn't seem more different from Dr. Vivian Bearing, the brilliant, emotionally remote English professor who is the heroine of her play WIT — which has won such unanimous critical acclaim in its small Off- Broadway production. Vivian is a 50-year-old scholar who has devoted her life to the study of John Donne's "Holy Sonnets." When we meet her, she is dying of very placement of a comma crystallizing mysteries of life and death for ovarian cancer. Bald from chemotherapy, she makes her entrance clad Vivian and her audience. For this feat, one critic demanded that Ms. Edson in a hospital gown, dragging an IV pole. -

Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding Also Play, the Booklet Presents a Description of the Prinipal Characters Mormons

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 835 CS 508 902 AUTHOR Carr, John C. TITLE "Angels in America Part 1: Millennium Approaches." Spotlight on Theater Notes. INSTITUTION John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE [95) NOTE 17p.; Produced by the Performance Plus Program, Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding also provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund. For other guides in this series, see CS 508 903-906. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Acquired Immune Defi-:ency Syndrome; Acting; *Cultural Enrichment; *Drama; Higher Education; Homophobia; Homosexuality; Interviews; Playwriting; Popular Culture; Program Descriptions; Secondary Education; United States History IDENTIFIERS American Myths; *Angels in America ABSTRACT This booklet presents a variety of materials concerning the first part of Tony Kushner's play "Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes." After a briefintroduction to the play, the booklet presents a description of the prinipal characters in the play, a profile of the playwright, information on funding of the play, an interview with the playwright, descriptions of some of the motifs in the play (including AIDS, Angels, Roy Cohn, and Mormons), a quiz about plays, biographical information on actors and designers, and a 10-item list of additional readings. (RS) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ****):***:%****************************************************)%*****)%* -

The Great Society Program Book Published February 2, 2018

THE GREAT SOCIETY 2017/18 SEASON COMING IN 2018 TO ARENA STAGE Part of the Women’s American Masterpiece Voices Theater Festival SOVEREIGNTY AUGUST WILSON’S NOW PLAYING THROUGH FEBRUARY 18 TWO TRAINS Epic Political Thrill Ride RUNNING THE GREAT SOCIETY MARCH 30 — APRIL 29 NOW PLAYING THROUGH MARCH 11 World-Premiere Musical Inspirational True Story SNOW CHILD HOLD THESE TRUTHS APRIL 13 — MAY 20 FEBRUARY 23 — APRIL 8 SUBSCRIBE TODAY! 202-488-3300 ARENASTAGE.ORG THE GREAT SOCIETY TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Artistically Speaking 5 From the Executive Director 6 Molly Smith’s 20th Anniversary Season 9 Dramaturg’s Note 11 Title Page 13 Time / Cast List 15 Bios — Cast 19 Bios — Creative Team 21 For this Production 23 Arena Stage Leadership ARENA STAGE 1101 Sixth Street SW Washington, DC 20024-2461 24 Board of Trustees / Theatre Forward ADMINISTRATION 202-554-9066 SALES OFFICE 202-488-3300 TTY 202-484-0247 25 Full Circle Society arenastage.org 26 Thank You — The Annual Fund © 2018 Arena Stage. All editorial and advertising material is fully protected and must not 29 Thank You — Institutional Donors be reproduced in any manner without written permission. 30 Theater Staff The Great Society Program Book Published February 2, 2018 Cover Illustration by Richard Davies Tom Program Book Staff Amy Horan, Associate Director of Marketing Shawn Helm, Graphic Designer 2017/18 SEASON 3 ARTISTICALLY SPEAKING Historians often argue whether history is cyclical or linear. The Great Society makes an argument for both sides of this dispute. Taking place during the most tumultuous days in Lyndon Baines Johnson’s (LBJ) second term, this play depicts the president fighting wars both at home and abroad as he faces opposition to his domestic programs and the role of the United States in the Vietnam War. -

MICHAEL DOVE Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, Member Email: [email protected] DIRECTING Theatre Play Author

MICHAEL DOVE Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, Member Email: [email protected] DIRECTING Theatre Play Author Olney Theatre Every Brilliant Thing* Duncan Macmillan Forum Theatre Love and Information Caryl Churchill Forum Theatre Building the Wall (WP) Robert Schenkkan Orlando Shakespeare Blackberry Winter Steve Yockey Forum Theatre I Call My Brothers Jonas Hassen Khemiri Forum Theatre Blackberry Winter (WP) Steve Yockey Playmakers Repertory Company Seminar* Theresa Rebeck 1st Stage When the Rain Stops Falling Andrew Bovell University of Maryland Human Capacity (WP) Jennifer Barclay Forum Theatre Passion Play Sarah Ruhl 1st Stage Doubt John Patrick Shanley Forum Theatre Pluto (WP) Steve Yockey Forum Theatre Agnes Under the Big Top Aditi Brennan Kapil Vermont Stage Company 4000 Miles Amy Herzog Forum Theatre Holly Down in Heaven (WP) Kara Lee Corthron Forum Theatre Church Young Jean Lee 1st Stage Sideman Warren Leight Montgomery College The Water Engine David Mamet Forum Theatre Mad Forest Caryl Churchill Angry Alice/Capital Fringe On the Rag To Riches K.Molinaro/S.Northrip Cape Fear Regional Theatre A View From the Bridge Arthur Miller Forum Theatre Scorched Wajdi Mouawad Forum Theatre Amazons and Their Men Jordan Harrison Forum Theatre Angels in America: PERESTROIKA Tony Kushner Source Festival The Relationship of Archibald & Amity…Elevator Eric Kalman Levitz Forum Theatre/Theater J Seven Jewish Children Caryl Churchill Forum Theatre dark play or stories for boys Carlos Murillo Montgomery College Metamorphoses Mary Zimmerman -

Drama Winners the First 50 Years: 1917-1966 Pulitzer Drama Checklist 1966 No Award Given 1965 the Subject Was Roses by Frank D

The Pulitzer Prizes Drama Winners The First 50 Years: 1917-1966 Pulitzer Drama Checklist 1966 No award given 1965 The Subject Was Roses by Frank D. Gilroy 1964 No award given 1963 No award given 1962 How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying by Loesser and Burrows 1961 All the Way Home by Tad Mosel 1960 Fiorello! by Weidman, Abbott, Bock, and Harnick 1959 J.B. by Archibald MacLeish 1958 Look Homeward, Angel by Ketti Frings 1957 Long Day’s Journey Into Night by Eugene O’Neill 1956 The Diary of Anne Frank by Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich 1955 Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams 1954 The Teahouse of the August Moon by John Patrick 1953 Picnic by William Inge 1952 The Shrike by Joseph Kramm 1951 No award given 1950 South Pacific by Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II and Joshua Logan 1949 Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller 1948 A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams 1947 No award given 1946 State of the Union by Russel Crouse and Howard Lindsay 1945 Harvey by Mary Coyle Chase 1944 No award given 1943 The Skin of Our Teeth by Thornton Wilder 1942 No award given 1941 There Shall Be No Night by Robert E. Sherwood 1940 The Time of Your Life by William Saroyan 1939 Abe Lincoln in Illinois by Robert E. Sherwood 1938 Our Town by Thornton Wilder 1937 You Can’t Take It With You by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman 1936 Idiot’s Delight by Robert E. Sherwood 1935 The Old Maid by Zoë Akins 1934 Men in White by Sidney Kingsley 1933 Both Your Houses by Maxwell Anderson 1932 Of Thee I Sing by George S. -

Revision, Nostalgia, and Resistance in Contemporary American Drama Sinan Gul University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 Persistence of Memory: Revision, Nostalgia, and Resistance in Contemporary American Drama Sinan Gul University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Gul, Sinan, "Persistence of Memory: Revision, Nostalgia, and Resistance in Contemporary American Drama" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2404. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2404 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Persistence of Memory: Revision, Nostalgia, and Resistance in Contemporary American Drama A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Sinan Gul Ege University Bachelors of Art in English Language and Literature, 2005 Dokuz Eylul University Master of Fine Arts in Stage Arts, 2010 August 2017 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation of the Graduate Council. _________________________ Robert Cochran, PhD Dissertation Director _________________________ _________________________ Dorothy Stephens, PhD Les Wade, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This dissertation focuses on the usages of memory in contemporary American drama. Analyzing selected mainstream and alternative dramatic texts, The Persistence of Memory is a study of personal and communal reflections of the past within contemporary plays. The introduction provides examples from modern plays, major terms, and vital concepts for memory studies and locates their merits in dramatic texts. -

Download 2018–2019 Catalogue of New Plays

Catalogue of New Plays 2018–2019 © 2018 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: Take a look at the “New Plays” section of this year’s catalogue. You’ll find plays by former Pulitzer and Tony winners: JUNK, Ayad Akhtar’s fiercely intelligent look at Wall Street shenanigans; Bruce Norris’s 18th century satire THE LOW ROAD; John Patrick Shanley’s hilarious and profane comedy THE PORTUGUESE KID. You’ll find plays by veteran DPS playwrights: Eve Ensler’s devastating monologue about her real-life cancer diagnosis, IN THE BODY OF THE WORLD; Jeffrey Sweet’s KUNSTLER, his look at the radical ’60s lawyer William Kunstler; Beau Willimon’s contemporary Washington comedy THE PARISIAN WOMAN; UNTIL THE FLOOD, Dael Orlandersmith’s clear-eyed examination of the events in Ferguson, Missouri; RELATIVITY, Mark St. Germain’s play about a little-known event in the life of Einstein. But you’ll also find plays by very new playwrights, some of whom have never been published before: Jiréh Breon Holder’s TOO HEAVY FOR YOUR POCKET, set during the early years of the civil rights movement, shows the complexity of choosing to fight for one’s beliefs or protect one’s family; Chisa Hutchinson’s SOMEBODY’S DAUGHTER deals with the gendered differences and difficulties in coming of age as an Asian-American girl; Melinda Lopez’s MALA, a wry dramatic monologue from a woman with an aging parent; Caroline V. McGraw’s ULTIMATE BEAUTY BIBLE, about young women trying to navigate the urban jungle and their own self-worth while working in a billion-dollar industry founded on picking appearances apart. -

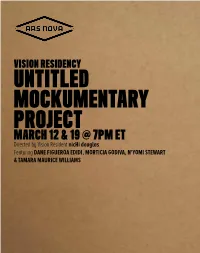

Mockumentary Project

VISION RESIDENCY UNTITLED MOCKUMENTARY PROJECT MARCH 12 & 19 @ 7PM ET Directed by Vision Resident nicHi douglas Featuring DANE FIGUEROA EDIDI, MORTICIA GODIVA, N'YOMI STEWART & TAMARA MAURICE WILLIAMS UNTITLED MOCKUMENTARY PROJECT EPISODES 1 & 2: MARCH 12 @ 7PM ET EPISODES 3 & 4: MARCH 19 @ 7 PM ET THE TEAM Directed by Vision Resident nicHi douglas Written & Performed by DANE FIGUEROA EDIDI, MORTICIA GODIVA, N'YOMI STEWART & TAMARA MAURICE WILLIAMS Director of Photography ADELE OVERBEY Co-Composers TROY ANTHONY & GABBY HENDERSON Music TROY ANTHONY Sound TERESA-ESMERALDA SANCHEZ Gaffer MARLEY CHAPMAN Producer ASHTON MUÑIZ Assistant Director AVA ELIZABETH NOVAK Production Manager & Community Engagement MELISSA MOWRY Production Assistant/Key Grip GALEN POWELL Music for Episode 4 Features the Song "Because of Love" Music & Lyrics GABBY HENDERSON Singer GABBY HENDERSON THE ARTISTS WOULD LIKE TO THANK All of Our Trans Sistren & Kin The World Over - Past, Present & Afro-Future Ars Nova operates on the unceded land of the Lenape peoples on the island of Manhahtaan (Mannahatta) in Lenapehoking, the Lenape Homeland. We acknowledge the brutal history of this stolen land and the displacement and dispossession of its Indigenous people. We also acknowledge that after there were stolen lands, there were stolen people. We honor the generations of displaced and enslaved people that built, and continue to build, the country that we occupy today. We gathered together in virtual space to watch this performance. We encourage you to consider the legacies of colonization embedded within the technology and structures we use and to acknowledge its disproportionate impact on communities of color and Indigenous peoples worldwide. -

American Theatre Magazine's Annual

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 3, 2013 CONTACT: Dafina McMillan [email protected] 212-609-5955 American Theatre Magazine’s Annual “Season Preview” Issue Announces Top 10 Most-Produced Plays New York, NY – American Theatre magazine, published by Theatre Communications Group (TCG), has released its annual October “Season Preview” issue, featuring the Top 10 Most-Produced Plays list. Based on the 2013-14 seasons reported by TCG’s Member Theatres in Theatre Profiles, the Top 10 list omits holiday themed shows (such as The Santaland Diaries and A Christmas Carol) as well as works by Shakespeare. The issue also features articles on successful playwright and actor relationships, musical adaptations of Shakespeare, and Robert Schenkkan’s two plays based on the life of President Lyndon Johnson. “The Top 10 Most-Produced Plays list is more than just an exciting snapshot of the upcoming season,” said Teresa Eyring, executive director of TCG. “It also takes the temperature of the kinds of stories our theatres feel compelled to tell. In 2013-14, TCG Member Theatres are wrestling with issues of class (Good People, Detroit), race (Clybourne Park, The Whipping Man), the legacy of progressive political movements (The Mountaintop, 4000 Miles) and those perennial favorites, sex (Venus in Fur) and family (Other Desert Cities, Tribes). It also marks the first time since 2005-6 that female playwrights make up half the list.” The 2013-14 Top 10 Most-Produced Plays list is as follows (a tie for the final slot makes this a Top 14): Venus in Fur (22) by David Ives Clybourne Park (16) by Bruce Norris Good People (14) by David Lindsay-Abaire Other Desert Cities (13) by Jon Robin Baitz The Mountaintop (13) by Katori Hall 4000 Miles (12) by Amy Herzog Tribes (12) by Nina Raine Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike (11) by Christopher Durang The Cat in the Hat (8) adapted by Katie Mitchell from Dr. -

Introducing the 2014 Season! Women

prologuemagazine for members fall 2013 logue Introducing The 2014 Season! Women Can Roar The Contents of Box 91 Toward Insurgency 2014 Season Prologue Angus Bowmer Theatre The Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s The Tempest magazine for members William Shakespeare Fall 2013 Directed by Tony Taccone Editor The Cocoanuts Catherine Foster Music and lyrics by Irving Berlin; book by George S. Kaufman, with additional text by Morrie Ryskind; adapted by Mark Bedard Design Directed by David Ivers Craig Stewart The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window Contributing Writers Lorraine Hansberry Julie Felise Dubiner, Associate Director, Directed by Juliette Carrillo American Revolutions: the United States History Cycle A Wrinkle in Time Catherine Foster, Senior Editor World Premiere Gwyn Hervochon, Digital Project Based on the book by Madeleine L’Engle Archivist Adapted and directed by Tracy Young Otis Ramsey-Zöe, Freelance Writer Kerry Reid, Freelance Writer The Great Society Amy E. Richard, Media and World Premiere Communications Manager Robert Schenkkan Commissioned by and co-produced with Seattle Repertory Theatre Production Associate Directed by Bill Rauch Beth Bardossi Thomas Theatre Proofreaders The Comedy of Errors Pat Brewer William Shakespeare Nan Christensen Directed by Kent Gash Oregon Shakespeare Festival Water by the Spoonful Artistic Director: Bill Rauch Quiara Alegría Hudes Executive Director: Cynthia Rider Directed by Shishir Kurup P.O. Box 158 Family Album Ashland, OR 97520 World Premiere Administration 541-482-2111 Book and lyrics by Stew;