Serhii Plokhy Mystifying the Nation: the History of the Rus' and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Udc 930.85:78(477.83/.86)”18/19” Doi 10.24919/2519-058X.19.233835

Myroslava NOVAKOVYCH, Olha KATRYCH, Jaroslaw CHACINSKI UDC 930.85:78(477.83/.86)”18/19” DOI 10.24919/2519-058X.19.233835 Myroslava NOVAKOVYCH PhD hab. (Art), Associate Professor, Professor of the Departmentof Musical Medieval Studies and Ukrainian Studies.Mykola Lysenko Lviv National Music Academy, 5 Ostapa Nyzhankivskoho Street, Lviv, Ukraine, postal code 79005 ([email protected]) ORСID: 0000-0002-5750-7940 Scopus-Author ID: 57221085667 Olha KATRYCH PhD (Art), Professor, Academic Secretary of the Academic Council, Mykola Lysenko Lviv National Music Academy, 5 Ostapa Nyzhankivskoho Street, Lviv, Ukraine, postal code 79005 ([email protected]) ORCID: 0000-0002-2222-1993 Scopus-Author ID: 57221111370 ResearcherID: AAV-6310-2020 Jaroslaw CHACINSKI PhD (Humanities), Assistant Professor, Head of the Department of Music Art, Pomeranian Academy in Slupsk, 27 Partyzanów Street, Slupsk, Poland, postal code 76-200 ([email protected]) ORCID: 0000-0002-3825-8184 Мирослава НОВАКОВИЧ доктор мистецтвознавства, доцент, професор кафедри музичної медієвістики та україністики Львівської національної музичної академії імені Миколи Лисенка, вул. Остапа Нижанківського, 5, м. Львів, Україна, індекс 79005 ([email protected]) Ольга КАТРИЧ кандидат мистецтвознавства, професор, вчений секретар Львівської національної музичної академії імені Миколи Лисенка, вул. Остапа Нижанківського, 5, м. Львів, Україна, індекс 79005 ([email protected]) Ярослав ХАЦІНСЬКИЙ доктор філософії (PhD humanities), доцент,завідувач кафедри музичного мистецтва Поморської академії,вул. Партизанів 27, м. Слупськ, Польща, індекс 76-200 ([email protected]) Bibliographic Description of the Article: Novakovych, M., Katrych, O. & Chacinski, J. (2021). The role of music culture in the processes of the Ukrainian nation formation in Galicia (the second half of the XIXth – the beginning of the XXth century). -

Visual Text and Musical Subtext: the Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): a 21St-Century Composer’S Journey in Silent Film Scoring

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Visual Text and Musical Subtext: The Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): A 21st-Century Composer’s Journey in Silent Film Scoring Robert Israel Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/38488 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.38488 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Robert Israel, “Visual Text and Musical Subtext: The Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): A 21st-Century Composer’s Journey in Silent Film Scoring”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 23 March 2021, connection on 26 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/38488 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/miranda.38488 This text was automatically generated on 26 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Visual Text and Musical Subtext: The Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): A 21st-Cen... 1 Visual Text and Musical Subtext: The Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): A 21st-Century Composer’s Journey in Silent Film Scoring Robert Israel 1 This piece aims to contextualize my contribution as ethnomusicologist, composer, orchestrator, arranger, conductor, choral director, producer, music contractor, and music editor for Turner Classic Movie’s presentation of MGM’s 1928 production of The Cossacks, directed by George Hill, with additional sequences directed by Clarence Brown. Working within a limited budget; doing research into the film’s historical era and the musical practices of the culture in which it takes place; finding source material, ethnic instruments, and musicians specializing in specific ethnic styles of music performance; and, other formidable challenges which I will outline here. -

Revue Des Études Slaves, LXXXV-3 | 2014 Taras Shevchenko: the Making of the National Poet 2

Revue des études slaves LXXXV-3 | 2014 Taras Ševčenko (1814-1861) Taras Shevchenko: The Making of the National Poet Taras Ševčenko: la fabrication d’un poète national George G. Grabowicz Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/res/398 DOI: 10.4000/res.398 ISSN: 2117-718X Publisher Institut d'études slaves Printed version Date of publication: 30 December 2014 Number of pages: 421-439 ISBN: 978-2-7204-0532-7 ISSN: 0080-2557 Electronic reference George G. Grabowicz, « Taras Shevchenko: The Making of the National Poet », Revue des études slaves [Online], LXXXV-3 | 2014, Online since 26 March 2018, connection on 14 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/res/398 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/res.398 This text was automatically generated on 14 December 2020. Revue des études slaves Taras Shevchenko: The Making of the National Poet 1 Taras Shevchenko: The Making of the National Poet Taras Ševčenko: la fabrication d’un poète national George G. Grabowicz 1 The bicentennial of Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861) coincided with a remarkable political and social upheaval—a revolution and a national renewal that as of this writing is still ongoing and still under attack in Ukraine.1 The core, and iconic, presence of Shevchenko in that process, and dramatically and symbolically on the Euromaidan itself, has often been noted and the revolutionary changes in which it was embedded will continue to draw the attention of political, sociological and cultural studies in the foreseeable future.2 If only through those manifest optics, Shevchenko was at the center of things in Ukraine—now, as often before. -

Dutch and Flemish Art in Russia

Dutch & Flemish art in Russia Dutch and Flemish art in Russia CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie) Amsterdam Editors: LIA GORTER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory GARY SCHWARTZ, CODART BERNARD VERMET, Foundation for Cultural Inventory Editorial organization: MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory WIETSKE DONKERSLOOT, CODART English-language editing: JENNIFER KILIAN KATHY KIST This publication proceeds from the CODART TWEE congress in Amsterdam, 14-16 March 1999, organized by CODART, the international council for curators of Dutch and Flemish art, in cooperation with the Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie). The contents of this volume are available for quotation for appropriate purposes, with acknowledgment of author and source. © 2005 CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory Contents 7 Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN 10 Late 19th-century private collections in Moscow and their fate between 1918 and 1924 MARINA SENENKO 42 Prince Paul Viazemsky and his Gothic Hall XENIA EGOROVA 56 Dutch and Flemish old master drawings in the Hermitage: a brief history of the collection ALEXEI LARIONOV 82 The perception of Rembrandt and his work in Russia IRINA SOKOLOVA 112 Dutch and Flemish paintings in Russian provincial museums: history and highlights VADIM SADKOV 120 Russian collections of Dutch and Flemish art in art history in the west RUDI EKKART 128 Epilogue 129 Bibliography of Russian collection catalogues of Dutch and Flemish art MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER & BERNARD VERMET Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN CODART brings together museum curators from different institutions with different experiences and different interests. The organisation aims to foster discussions and an exchange of information and ideas, so that professional colleagues have an opportunity to learn from each other, an opportunity they often lack. -

Serhii Plokhy Mapping the Great Famine One of the Most Insightful

Serhii Plokhy Mapping the Great Famine One of the most insightful and moving eyewitness accounts of the Holodomor, or the Great Ukrainian Famine of 1932–33, was written by Oleksandra Radchenko, a teacher in the Kharkiv region of Ukraine. In her diary, which was confiscated by Stalin’s secret police and landed the author in the Gulag for ten long years, the 36-year-old teacher recorded not only what she saw around her but also what she thought about the tragedy unfolding before her eyes. “I am so afraid of hunger; I’m afraid for the children,” wrote Radchenko, who had three young daughters, in February 1932. “May God protect us and have mercy on us. It would not be so offensive if it were due to a bad harvest, but they have taken away the grain and created an artificial famine.” That year she wrote about the starvation and suffering of her neighbors and acquaintances but recorded no deaths from hunger. It all changed in January 1933, when she encountered the first corpse of a famine victim on the road leading to her home. By the spring of 1933, she was regularly reporting mass deaths from starvation. “People are dying,” wrote Radchenko in her entry for May 16, 1933, “…they say that whole villages have died in southern Ukraine.”1 Was Radchenko’s story unique? Did people all over Ukraine indeed suffer from starvation in 1932 and then start dying en masse in 1933? Which areas of Ukraine were most affected? Was there a north-south divide, as the diary suggests, and, if so, did people suffer (and die) more in the south than in the north? Were there more deaths in the villages than in towns and cities? Were small towns affected? Did ethnicity matter? These are the core questions that Mapa, the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute’s Digital Map of Ukraine Project is attempting to answer by developing a Geographic Information System (GIS)-based Digital Atlas of the Holodomor. -

The Last Empire: the Final Days of the Soviet Union

The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union https://www.carnegiecouncil.org/studio/multimedia/20140602/i... The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union Public Affairs Serhii Plokhy, Joanne J. Myers Transcript Introduction JOANNE MYERS: Good morning. I'm Joanne Meyers, director of Public Affairs programs of the Carnegie Council. I would like to welcome our members, guests, and C‑SPAN Book TV to this Public Affairs program. Our guest today is Serhii Plokhy. He is professor of Ukraine history and the director of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University. His book, The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union, will, as he writes, not only lift the curtain of time on the dramatic events leading up to the lowering of the Soviet flag and the collapse of the Soviet Union, but it will also provide a much-needed context for what is happening in Ukraine today. The longstanding narrative of the end of the Cold War is one that has entwined the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the triumph of democratic values over communism. It is a narrative that has persisted for decades, with adverse consequences for America's standing in the world and the perception of what we could accomplish. But for Putin, the collapse of the Soviet Union was, as he has often said, the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century. This, in turn, has led many Western analysts to accuse him of using this current crisis to rewrite the history of the Soviet collapse and resurrect the Soviet empire. -

Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Security for More Information on This Publication, Visit

Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Security Russia, NATO, C O R P O R A T I O N STEPHEN J. FLANAGAN, ANIKA BINNENDIJK, IRINA A. CHINDEA, KATHERINE COSTELLO, GEOFFREY KIRKWOOD, DARA MASSICOT, CLINT REACH Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Security For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA357-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0568-5 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Cover graphic by Dori Walker, adapted from a photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Weston Jones. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The Black Sea region is a central locus of the competition between Russia and the West for the future of Europe. -

The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine Prelims.Z3 24/9/01 11:20 AM Page Ii Prelims.Z3 24/9/01 11:20 AM Page Iii

prelims.z3 24/9/01 11:20 AM Page i The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine prelims.z3 24/9/01 11:20 AM Page ii prelims.z3 24/9/01 11:20 AM Page iii The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine SERHII PLOKHY 3 prelims.z3 24/9/01 11:20 AM Page iv 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Serhii Plokhy The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Plokhy, Serhii. -

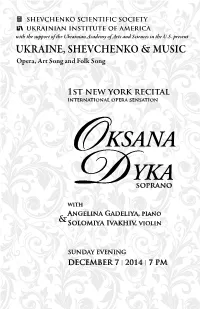

Concert Program

Oksana Dyka, soprano Angelina Gadeliya, piano • Solomiya Ivakhiv, violin I. Bellini Vincenzo Bellini Casta Diva (1801-1835) from Norma (1831) Program Mozart Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro (1756-1791) from The Marriage of Figaro (1786) Rossini Gioachino Rossini Selva opaca, Recitative and Aria (1792-1868) from Guglielmo Tell (William Tell, 1829) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya II. Shchetynsky Alexander Shchetynsky An Episode in the Life of the Poet, (b. 1960) an afterword to the opera Interrupted Letter (2014) World Premiere Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya III. From Poetry to Art Songs 1: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Shtoharenko Andriy Shtoharenko Yakby meni cherevyky (1902-1992) (If I had a pair of shoes, 1939) Silvestrov Valentin Silvestrov Proshchai svite (b. 1937) (Farewell world, from Quiet Songs, 1976) Shamo Ihor Shamo Zakuvala zozulen’ka (1925-1982) (A cuckoo in a verdant grove, 1958) Skoryk Myroslav Skoryk Zatsvila v dolyni (b. 1938) (A guelder-rose burst into bloom, 1962) Mussorgsky Modest Mussorgsky Hopak (1839-1881) from the opera Sorochynsky Fair (1880) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya 2 Program — INTERMISSION — I V. Beethoven Ludwig van Beethoven Allegro vivace (1770-1827) from Sonata in G Major, Op. 30 (1801-1802) Vieuxtemps Henri Vieuxtemps Désespoir (1820-1881) from Romances sans paroles, Op. 7, No. 2 (c.1845) Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya V. From Poetry to Art Songs 2: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Lysenko Mykola Lysenko Oy, odna ya odna (1842-1912) (I’m alone, so alone, 1882) Rachmaninov Sergei Rachmaninov Poliubila ya na pechal’ svoyu, (1873-1943) Op. 8, No. 4 (I have given my love, 1893) Stetsenko Kyrylo Stetsenko Plavai, plavai, lebedon’ko (1882-1922) (Swim on, swim on, dear swan, 1903) Dankevych Konstantyn Dankevych Halia’s Aria (1905-1984) from the opera Nazar Stodolia (1960) VI. -

Romantic Poetry 1 Romantic Poetry

Romantic poetry 1 Romantic poetry Romanticism, a philosophical, literary, artistic and cultural era[1] which began in the mid/late-18th century[2] as a reaction against the prevailing Enlightenment ideals of the day (Romantics favored more natural, emotional and personal artistic themes),[3][4] also influenced poetry. Inevitably, the characterization of a broad range of contemporaneous poets and poetry under the single unifying name can be viewed more as an exercise in historical The Funeral of Shelley by Louis Edouard Fournier (1889); the group members, from left compartmentalization than an attempt to right, are Trelawny, Hunt and Byron to capture the essence of the actual ‘movement’.[citation needed] Poets such as William Wordsworth were actively engaged in trying to create a new kind of poetry that emphasized intuition over reason and the pastoral over the urban, often eschewing consciously poetic language in an effort to use more colloquial language. Wordsworth himself in the Preface to his and Coleridge's Lyrical Ballads defined good poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,” though in the same sentence he goes on to clarify this statement by In Western cultural context romanticism substantially contibuted to the idea asserting that nonetheless any poem of of "how a real poet should look like". An idealized statue of a Czech poet value must still be composed by a man Karel Hynek Mácha (in Petřín Park, Prague) repesents him as a slim, tender “possessed of more than usual organic and perhaps unhealthy boy. However, anthropological examination proved sensibility [who has] also thought long that he was a man of a strong, robust and muscular body constitution. -

Lost Kingdom: the Quest for Empire and the Making of the Russian Nation, from 1470 to the Present by Serhii Plokhy

2018-066 6 August 2018 Lost Kingdom: The Quest for Empire and the Making of the Russian Nation, from 1470 to the Present by Serhii Plokhy . New York: Basic Books, 2017. Pp. xiii, 398, ISBN 978–0–465–09849–1. Review by Greg Simons, Uppsala University ([email protected]). In this book, Serhii Plokhy,1 the Mykhailo Hrushevsky Professor of Ukrainian history at Harvard University, traces the changing political ideas and historical events that have shaped Russian na- tional identity since the fifteenth century. It consists of an introduction, twenty chapters distrib- uted in six parts,2 and an epilogue. Though the book proceeds chronologically, much greater attention is paid to the period up to the Russian Revolution and Civil War. The logic for the book is well put on its dust cover: In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea and launched hybrid warfare in eastern Ukraine. The conflict pro- duced the worst crisis in East-West relations since the end of the Cold War and led to election- meddling scandals in the United States and in France. The Western world was shocked and out- raged, but these blatant violations of national sovereignty were only the latest iterations of a centu- ries-long effort to expand Russian boundaries, create a pan-Russian nation, and assert Russian power in Eastern Europe and beyond. The book’s content falls into two unequal parts. The most space is given to an engaging, de- tailed study of five centuries of Russian history. The rest of the book, concerning present-day de- velopments, is more speculative and politically biased.