Like Dreamers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aliya Chalutzit from America, 1939-48

1 Aliya of American Pioneers By Yehuda Sela (Silverman) From Hebrew: Arye Malkin A) Aliya1 Attempts During WW II The members of the Ha‟Shomer Ha‟Tzair2 Zionist Youth Movement searched a long time for some means to get to the shores of the Land of Israel (Palestine). They all thought that making Aliya was preferable to joining the Canadian or the American Army, which would possibly have them fighting in some distant war, unrelated to Israel. Some of these efforts seem, in retrospect, unimaginable, or at least naïve. There were a number of discussions on this subject in the Secretariat of Kibbutz Aliya Gimel (hereafter: KAG) and the question raised was whether individual private attempts to make Aliya should be allowed. The problems were quite complicated, and rather than deciding against the effort to make Aliya, it was decided to allow these efforts in special cases. Later on the Secretariat decided against these private individual efforts. The members attempted several ways to pursue this goal, but none were successful. Some applied for a truck driver position with a company that operated in Persia, building roads to connect the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea. Naturally, holding a driving license that did not qualify one for heavy vehicles did not help. Another way was to volunteer to be an ambulance driver in the Middle East, an operation that was being run by the Quakers; this was a pacifist organization that had carried out this sort of work during the First World War. An organization called „The American Field Service‟ recruited its members from the higher levels of society. -

Project Aim and Objectives

1 MICROZONING OF THE EARTHQUAKE HAZARD IN ISRAEL PROJECT 9 SITE SPECIFIC EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS ASSESSMENT USING AMBIENT NOISE MEASUREMENTS IN HADERA, PARDES HANNA, BINYAMINA AND NEIGHBORING SETTLEMENTS November, 2009 Job No 526/473/09 Principal Investigator: Dr. Yuli Zaslavsky Collaborators G. Ataev, M. Gorstein, M. Kalmanovich, D. Giller, I. Dan, N. Perelman, T. Aksinenko, V. Giller, and A. Shvartsburg Submitted to: Earth Sciences Research Administration National Ministry of Infrastructures Contract Number: 28-17-054 2 CONTENT LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................... 4 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 7 Empirical approaches implemented in the analysis of site effect ................................................ 8 GEOLOGICAL OUTLINE ............................................................................................................ 10 Quaternary sediments ................................................................................................................. 12 Tertiary rocks ............................................................................................................................ -

Ian S. Lustick

MIDDLE EAST POLICY, VOL. XV, NO. 3, FALL 2008 ABANDONING THE IRON WALL: ISRAEL AND “THE MIDDLE EASTERN MUCK” Ian S. Lustick Dr. Lustick is the Bess W. Heyman Chair of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of Trapped in the War on Terror. ionists arrived in Palestine in the the question of whether Israel and Israelis 1880s, and within several de- can remain in the Middle East without cades the movement’s leadership becoming part of it. Zrealized it faced a terrible pre- At first, Zionist settlers, land buyers, dicament. To create a permanent Jewish propagandists and emissaries negotiating political presence in the Middle East, with the Great Powers sought to avoid the Zionism needed peace. But day-to-day intractable and demoralizing subject of experience and their own nationalist Arab opposition to Zionism. Publicly, ideology gave Zionist leaders no reason to movement representatives promulgated expect Muslim Middle Easterners, and false images of Arab acceptance of especially the inhabitants of Palestine, to Zionism or of Palestinian Arab opportuni- greet the building of the Jewish National ties to secure a better life thanks to the Home with anything but intransigent and creation of the Jewish National Home. violent opposition. The solution to this Privately, they recognized the unbridgeable predicament was the Iron Wall — the gulf between their image of the country’s systematic but calibrated use of force to future and the images and interests of the teach Arabs that Israel, the Jewish “state- overwhelming majority of its inhabitants.1 on-the-way,” was ineradicable, regardless With no solution of their own to the “Arab of whether it was perceived by them to be problem,” they demanded that Britain and just. -

Parries Hanna

637 Parries Hanna Horvitz & Horvitz Book & Nwsppr Agcy Leitner Benjamin Hadar Ins Co Ltd Mossenson Zipora & Amos Ricss Shalom (near Egged Bus Stn) . .70 97 Derech Karkur 74 83 56 Talmei Elazar 73 82 5 Shikun Rassco 72 26 Rifer Hana & Yehoshua Hospital Neve Shalvah Ltd 70 58 Lcnshitzki Shelomo Butchershop.. .72 67 Motro Samuel Car Dealer Rehov Harishonim Karkur 74 33 Levi Hermann & Lucie Rehov Harishonim 74 69 Robeosohn Dr Friedrich Rehov Ha'atzmaut Karkur 73 51 Mozes Walter Farmer Shekhunat Meged 70 30 Levit Abraham Devora & Thiya Rehov Habotnim 71 93 Robinson Abraham Derech Hanadiv71 18 Invalids Home Tel Alon Karkur 73 94 Mueller Sbelomit Rehov Hadekalim .70 34 Roichman Bros (Shomron) Ltd (near Meged) 72 83 Mahzevet Iron 74 43 Inwald F A Rehov Hanassi 73 95 Levy Otto Farmer Rehov Habotnim .72 09 Rosenau Chana Rehov Habotnim .74 79 Inwentash Josef Metal Wks Levy Tclma & Gad N Rosenbaum Dr Julius Phys Rehov Harishonim 74 36 Shechunat Rassco 21 74 24 Nachimovic Hava & Lipa Gan Hashomron 71 75 Iron Co-op Bakery Ltd Karkur .. .70 72 Lewi David Pension Kefar Pines . .73 40 Rehov Hapalmah 73 61 Rotenberg Abraham Agric Machs Lewin Ernst Jehuda Ishaky Dov Fuel & Lubr Stn Nadaf Rashid Mussa Farmer Moshav Talmei Elazar 71 12 Shekhunat Meged 72 56 Shikun Ammami 23 Karkur 73 29 Baqa El Gharbiya 71 53 Rubinstein Ami-Netzah Bet Olim D' .72 58 Liptscher Katricl & Menahem Crpntry Itin Shoshana & Ben-Zion Nattel Jacob Agcy of Carmei Oriental Rubinstein Hayim Derech Hanadiv . .71 50 Rehov Gilad 71 89 Rehov Hadekalim 70 94 Wines & Nesher Beer Lishkat Hammas Karkur 72 94 Itzkovits Aharon Car Elecn Rehov Haharuvim 72 69 S Pardes Hanna Rehov Hadkalim .70 73 Main Rd 74'40 Neumann Miriam & Kurt Local Council Baqa El Gharbiya 72 23 Sachs Dr Yehuda Gan Hashomron. -

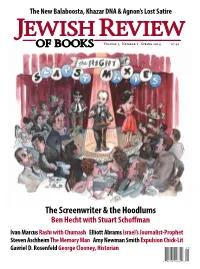

JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95

The New Balaboosta, Khazar DNA & Agnon’s Lost Satire JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95 The Screenwriter & the Hoodlums Ben Hecht with Stuart Schoffman Ivan Marcus Rashi with Chumash Elliott Abrams Israel’s Journalist-Prophet Steven Aschheim The Memory Man Amy Newman Smith Expulsion Chick-Lit Gavriel D. Rosenfeld George Clooney, Historian NEW AT THE Editor CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY Abraham Socher Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Associate Editor Amy Newman Smith Administrative Assistant Rebecca Weiss Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Publisher Eric Cohen Associate Publisher & Director of Marketing Lori Dorr NEW SPACE The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, The David Berg Rare Book Room is a state-of- Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication the-art exhibition space preserving and dis- of ideas and criticism published in Spring, Summer, playing the written word, illuminating Jewish Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 165 East 56th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022. history over time and place. For all subscriptions, please visit www.jewishreviewofbooks.com or send $29.95 UPCOMING EXHIBITION ($39.95 outside of the U.S.) to Jewish Review of Books, Opening Sunday, March 16: By Dawn’s Early PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834. Please send notifi- cations of address changes to the same address or to Light: From Subjects to Citizens (presented by the [email protected]. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor Ebook Free Download

LETTERS TO MY PALESTINIAN NEIGHBOR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Yossi Klein Halevi | 224 pages | 24 Sep 2019 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780062844927 | English | New York, United States Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor PDF Book And we were at stages that actually drafted solutions. In lyrical, evocative language, he unravels the complex strands of faith, pride, anger and anguish he feels as a Jew living in Israel, using history and personal experience as his guide. And that will hopefully trigger a different kind of conversation-- an internal Israeli conversation, which is badly needed on the Palestinian issue, because even today, on the left, there is an avoidance of a real conversation about the future of our relationship with the Palestinians. I know of no other occupation, certainly in memory, where the occupying power not only worried that in ceding territory it would be diminished, but actually worries that in ceding territory it may not be able to adequately defend itself, which is an acute worry among many Israeli Jews, a worry that I share. And we we're engaged in this for the last at least 1, years, since Islam came into the picture-- competing over identity and competing over the position of the victim. You know, in America, there used to be a saying. And so what I've tried to do is create a language for Israeli Jews like myself who don't come from the left-- I come from the center, from the political center-- and for whom the subject of peace leaves many of us tongue-tied. English and Hebrew options are available for purchase wherever you can buy books. -

Halevi Thursday, November 2 3:00 – 5:00 Pm Cross-Cultural Center – Communidad Room Yossi Klein Halevi Is a Senior Fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem

University of California, San Diego STUDENTS are cordially invited to attend What Muslims and Jews Need From Each Other Coffee, cookies, and conversation with Yossi Klein Halevi Thursday, November 2 3:00 – 5:00 pm Cross-Cultural Center – Communidad Room Yossi Klein Halevi is a senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. Together with Imam Abdullah Antepli of Duke University, he Co- direCts the Institute’s Muslim Leadership Initiative. Yossi is the author of Like Dreamers: The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation, published by HarperCollins in 2013, whiCh won the Jewish Book CounCil's Everett Family Foundation Jewish Book of the Year Award. He is also author of the 2001 book, At the Entrance to the Garden of Eden: A Jew's Search for God with Christians and Muslims in the Holy Land. The novelist Cynthia OziCk Called At the Entrance "a permanent masterwork." The former ArChbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Rowan Williams, called it “extraordinary and heartbreaking…a book full of wonders.” Yossi's first book, Memoirs of a Jewish Extremist, told the story of his teenage attraction to, and subsequent disillusionment with Jewish militanCy. The New York Times called it “a book of burning importance.” Yossi has been aCtive in Middle East reConciliation work, and serves as chairman of Open House, an Arab Israeli-Jewish Israeli Center in the town of Ramle, near Tel Aviv. Yossi was one of the founders of the now-defunct Israeli- Palestinian Media Forum, whiCh brought together Israeli and Palestinian journalists. He was a senior fellow at the Shalem Center in Jerusalem from 2003-2009. -

Front Matter May 8

LINGUISTIC AND SPATIAL PRACTICE IN A DIVIDED LANDSCAPE by Abigail Sone A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of PhD Graduate Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by Abigail Sone 2009 LINGUISTIC AND SPATIAL PRACTICE IN A DIVIDED LANDSCAPE Abigail Sone Department of Anthropology University of Toronto PhD 2009 Abstract of Thesis This dissertation demonstrates how changes in spatial boundaries map on to changes in the boundaries of national belonging through an ethnography of linguistic and spatial practice in a divided landscape. In Israel, as in many places around the globe, new forms of segregation have emerged in recent years, as violence and the fear of violence become increasingly bound up with the production of social difference and exclusion. In Wadi Ara, a valley in the north of the country where my fieldwork was based, segregation between Jewish and Palestinian citizens has dramatically increased since the fall of 2000, as the place of Palestinians in a Jewish state is being reconfigured. In this dissertation I focus on the changing movements and interactions of Jewish Israelis in Wadi Ara as they articulate with changes in the ways difference, belonging, and citizenship are organized on a national scale. I examine how increased hostility, fear, and distrust have become spatialized; how narratives of the past shape contemporary geographies; how competing ways of interpreting and navigating the landscape are mediated; and how particular forms of encounter are framed. My central argument is that through daily linguistic and spatial practice people in Wadi Ara do more than just make sense of shifting boundaries; they bring these boundaries into being and, in the process, they enact both self‐definition and exclusion, reflecting and circumscribing ii the changing place of Palestinians in Israel. -

The Old Courtyard at Kibbutz Ein Shemer in Israel, Fun, Attractions, Must See

The old courtyard at Kibbutz Ein Shemer in Israel, fun, attractions, must see... file:///C:/Users/uniqo3/Desktop/WORK/UNiQO/customers/courtyard/N... Tractors in Kibbutz Ein Shemer, Israel Kibbutz Ein Shemer hosts one of the most amazing early and completely restored collection of tractors at the "Michael Hanger". What makes this collection so unique is the amount of detailed work invested by our team to restore the tractors back to their original condition sometimes as early as 1875! Come visit history in the making at Kibbutz Ein Shemer. Please confirm the business hours for both museum and tractor hanger by phone +972-4-637-4237 or by email [email protected]. Motorized plow "Stock" Stock type tractor restoration from (Germany, 1910) 1917 Imported to Israel in 1912. The motorized plow, Developed in 1910 by a German which was called “The Mechanical Mule,” was one engineer named Robert Stock in his stage in the transition from horse-drawn plowing tractor factory. This tractor was to tractor plowing. equipped with gasoline engine with two cylinders gearbox. A standard horse-drawn tractor is attached at the In 1915, two tractors were brought to rear. Instead of the horses, the plow is towed by Israel by German Templars, who puller wheels powered by a gasoline engine. From established a farm near Beit Shean. We the premises of Nira and Yehuda Lerner, Gedera. received the tractor in very poor shape, motor gear was destroyed and the body Stationary threshing machine corn on the cob of the tractor was rusted. USA, 1920) After nearly two years of detailed Corn-threshing machines were imported to Israel restoration this tractor is now displayed at the beginning of the 20th century. -

Program Book 11-12 Webversion.Pub

2011-2012 / 5772 Prog ram Book Professional & Administrative Teams Table of Contents Rabbi Neal Gold [email protected] • Temple Shir Tikva Mitzvah Day…………………...4 Rabbi Greg Litcofsky [email protected] • Yossi Klein Halevi…………………………………….5 Cantor Hollis Schachner [email protected] • Meah: Inspired Jewish Learning……………………6 Rabbi Herman Blumberg, Emeritus • Jewish Explorations Weekend– Storahtelling ……..7 [email protected] David Passer , ext. 214 • Congregational Learning: Executive Director Sunday Morning Education Options………….8-9 [email protected] Deena Bloomstone , ext. 201 Monday Education Options……………………..10 Director of Congregational Wednesday Evening Education Options…...10-11 Learning [email protected] • Families With Young Children………………...12-13 Rachel Kest , ext. 203 Director of Elementary • & Family Education Religious School…………………………………14-15 [email protected] • Youth Community……………………………….16-17 Samantha Nidenberg , ext. 202 Youth Educator • [email protected] Worship/Choirs…………………………………..18-19 Karen Edwards, ext. 210 • Assistant to the Rabbis and Cantor Brotherhood and Sisterhood…………………...20-21 [email protected] • Reyim…………………………………………………21 Linda Goldbaum, ext. 211 Office Administrator • [email protected] Tikkun Olam………….……………………………...22 Toni Spitzer, ext.200 • Committees of Temple Shir Tikva………………...23 Office Administrator [email protected] • Board of Trustees & Committee Chairs…………..24 Lucy Dube , ext. 215 Bookkeeper bookkeeper@shirtikva. org Mike Buianowski Custodian -

The PUA English Report 2011-2012

Editor: Nurit Felter-Eitan, Authority Secretary & Spokeswoman All information provided in this report is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute a legal act. The hebrew translation is the current and accurate information. Information in this report is subject to change without prior notice. Greetings, I am delighted to hereby present the Israel Public Utility Authority’s (Electricity) biennial activity report for the years 2012-2011. This report summarizes the Authority’s Assembly’s extensive and meticulous work, assisted by the Authority’s team of professional employees, over the past two years, signifying a turning point in the Israeli electricity and energy markets. Alongside a severe energy crisis that befell the electricity market in the past two years due to the discontinuation of natural gas supply from Egypt and the creation of a gas supply monopoly, these years have seen a historic change in the electricity market, commencing with the admission of private electricity entrepreneurship and clean electricity production in significant capacities (the Authority’s projection for private electricity production is 25% by 2016, and approximately 10% for electricity production using renewable energy by 2020). As a result of the natural gas crisis, which began in 2011 due to recurring explosions in the gas lines leading from Egypt to Israel, the Electricity Authority was faced with a reality that would have forced it to instantly and radically increase in the electricity tariffs for the Israeli consumers in 2012. These circumstances led the Authority to combine forces with government bodies, including the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Energy and Water Resources and the Ministry of Environmental Protection, and lead a comprehensive move which significantly restrained the tariff increase, and furthermore, relieved the electricity consumers’ burden in a manner that enabled spreading the tariff increase over three years.