Asian Alpine E-News Issue No.25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications By Name: Syeda Batool National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 1 The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications by Name: Syeda Batool M.Phil Pakistan Studies, National University of Modern Languages, 2019 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY in PAKISTAN STUDIES To FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF PAKISTAN STUDIES National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 @Syeda Batool, April 2019 2 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THESIS/DISSERTATION AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Social Sciences for acceptance: Thesis/ Dissertation Title: The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications Submitted By: Syed Batool Registration #: 1095-Mphil/PS/F15 Name of Student Master of Philosophy in Pakistan Studies Degree Name in Full (e.g Master of Philosophy, Doctor of Philosophy) Degree Name in Full Pakistan Studies Name of Discipline Dr. Fazal Rabbi ______________________________ Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Prof. Dr. Shahid Siddiqui ______________________________ Signature of Dean (FSS) Name of Dean (FSS) Brig Muhammad Ibrahim ______________________________ Name of Director General Signature of -

Expeditions & Treks 2008/2009

V4362_JG_Exped Cover_AW 1/5/08 15:44 Page 1 Jagged Globe NEW! Expeditions & Treks www.jagged-globe.co.uk Our new website contains detailed trip itineraries 2008 for the expeditions and treks contained in this brochure, photo galleries and recent trip reports. / 2009 You can also book securely online and find out about new trips and offers by subscribing to our email newsletter. Jagged Globe The Foundry Studios, 45 Mowbray Street, Sheffield S3 8EN United Kingdom Expeditions Tel: 0845 345 8848 Email: [email protected] Web: www.jagged-globe.co.uk & Treks Cover printed on Take 2 Front Cover: Offset 100% recycled fibre Mingma Temba Sherpa. sourced only from post Photo: Simon Lowe. 2008/2009 consumer waste. Inner Design by: pages printed on Take 2 www.vividcreative.com Silk 75% recycled fibre. © 2007 V4362 V4362_JG_Exped_Bro_Price_Alt 1/5/08 15:10 Page 2 Ama Dablam Welcome to ‘The Matterhorn of the Himalayas.’ Jagged Globe Ama Dablam dominates the Khumbu Valley. Whether you are trekking to Everest Base Camp, or approaching the mountain to attempt its summit, you cannot help but be astounded by its striking profile. Here members of our 2006 expedition climb the airy south Expeditions & Treks west ridge towards Camp 2. See page 28. Photo: Tom Briggs. The trips The Mountains of Asia 22 Ama Dablam: A Brief History 28 Photo: Simon Lowe Porter Aid Post Update 23 Annapurna Circuit Trek 30 Teahouses of Nepal 23 Annapurna Sanctuary Trek 30 The Seven Summits 12 Everest Base Camp Trek 24 Lhakpa Ri & The North Col 31 The Seven Summits Challenge 13 -

Contributors

Contributors GEORGE BAND was the youngest member of the 1953 Everest team. He subsequently made the first ascent (with Joe Brown) of Kangchenjunga, and climbed in Peru and the Caucasus. In 1985 he climbed the Old Man of Hoy; in 1991 Ngum Tang Gang III (5640m) in Bhutan. AC President 1987-89. PHILIP BARTLETT lives in West Yorkshire. He prefers exploratory moun taineering to rock climbing as he gets older and his arms get weaker. In 1992 he explored the Lemon mountains in East Greenland. CHRIS BONINGTON CBE crowned his distinguished career in 198'5 by reaching the summit of Everest at the age of 50. He continues climbing and writing at undiminished pace. His latest book Sea, Ice and Rock was pub lished in 1992. TREVOR BRAHAM is a company director. He has been on 14 expeditions to the Himalaya, Karakoram and Hindu Kush. He wrote Himalayan Odyssey and was Editor of the Himalayan Journal 1958-60 and of Chronique Hima layenne (SAC) 1976-86. HAMISH BROWN is a travel writer based in Scotland, when not wandering worldwide or making extended visits to Morocco. His latest book From the Pennines to the Highlands. A Walking Route through the Scottish Borders was published in 1992. ROB COLLISTER is a mountain guide, happily married with three children, who lives in North Wales. He regards himself as 'one of Fortune's favoured few' (in Churchill's phrase) who can earn a living doing what they love. DAVID COX is a retired Oxford don. He climbed regularly in the UK and the Alps between 1954 and 1958 and was on Machapuchare (Nepal) in 1957. -

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

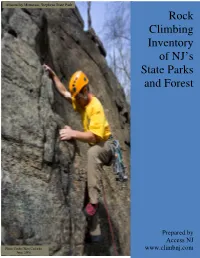

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

Gear Brands List & Lexicon

Gear Brands List & Lexicon Mountain climbing is an equipment intensive activity. Having good equipment in the mountains increases safety and your comfort level and therefore your chance of having a successful climb. Alpine Ascents does not sell equipment nor do we receive any outside incentive to recommend a particular brand name over another. Our recommendations are based on quality, experience and performance with your best interest in mind. This lexicon represents years of in-field knowledge and experience by a multitude of guides, teachers and climbers. We have found that by being well-equipped on climbs and expeditions our climbers are able to succeed in conditions that force other teams back. No matter which trip you are considering you can trust the gear selection has been carefully thought out to every last detail. People new to the sport often find gear purchasing a daunting chore. We recommend you examine our suggested brands closely to assist in your purchasing decisions and consider renting gear whenever possible. Begin preparing for your trip as far in advance as possible so that you may find sale items. As always we highly recommend consulting our staff of experts prior to making major equipment purchases. A Word on Layering One of the most frequently asked questions regarding outdoor equipment relates to clothing, specifically (and most importantly for safety and comfort), proper layering. There are Four basic layers you will need on most of our trips, including our Mount Rainier programs. They are illustrated below: Underwear -

2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook

Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook Allison Swanson [Basic Course Chair] Cebe Wallace [Meet and Greet, Reunion] Diane Gaddis [SIG Organization] Glenn Eades [Graduation] Jan Abendroth [Field Trips] Jeneca Bowe [Lectures] Jared Bowe [Student Tracking] Jim Nelson [Alpine Fashionista, North Cascades Connoisseur] Liana Robertshaw [Basic Climbs] Vineeth Madhusudanan [Enrollment] Fred Beckey, photograph in High Adventure, by Ira Spring, 1951 In loving memory Fred Page Beckey 1 [January 14, 1923 – October 30, 2017] Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 BASIC ALPINE CLIMBING COURSE STUDENT HANDBOOK COURSE OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................ 3 Class Meetings ............................................................................................................................ 3 Field Trips ................................................................................................................................... 4 Small Instructional Group (SIG) ................................................................................................. 5 Skills Practice Nights .................................................................................................................. 5 References ................................................................................................................................... 6 Three additional -

Scenes from the 20Th Century

Scenes from the 20th Century REINHOLD MESSNER An Essay for the New Millennium Based on a lecture given at the Alpine Club Symposium: 'Climbing into the Millennium - Where's it Going?' at Sheffield Hallam University on 6 March 1999 erhaps I'm the right age now, with the right perspective to view Pmountaineering, both its past and its future. Enough time has elapsed between my last eight-thousander and my first heart attack for me to be able to look more calmly at what it is we do. I believe it will not be easy for us to agree on an ethic that will save mountaineering for the next millennium. But in our search for such an ethic we first need to ask ourselves what values are the most important to us, both in our motivation for going to the mountains and on the mountains themselves. The first and most important thing I want to say has to do with risk. If we go to the mountains and forget that we are taking a risk, we will make mistakes, like those tourists recently in Austria who were trapped in a valley hit by an avalanche; 38 of them were killed. All over Europe people said: 'How could 38 people die in an avalanche? They were just on a skiing holiday.' They forgot that mountains are dangerous. But it's also important to remember that mountains are only dangerous if people are there. A mountain is a mountain; its basic existence doesn't pose a threat to anyone. It's a piece of rock and ice, beautiful maybe, but dangerous only if you approach it. -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

K2 Base Camp and Gondogoro La Trek

K2 And Gondogoro La Trek, Pakistan This is a trekking holiday to K2 and Concordia in the Karakoram Mountains of Pakistan followed by crossing the Gondogoro La to Hushe Valley to complete a superb mountaineering journey. Group departures See trip’s date & cost section Holiday overview Style Trek Accommodation Hotels, Camping Grade Strenuous Duration 23 days from Islamabad to Islamabad Trekking / Walking days On Trek: 15 days Min/Max group size 1 / 8. Guaranteed to run Meeting point Joining in Islamabad, Pakistan Max altitude 5,600m, Gondogoro Pass Private Departures & Tailor Made itineraries available Departures Group departures 2021 Dates: 20 Jun - 12 Jul 27 Jun - 19 Jul 01 Jul - 23 Jul 04 Jul - 26 Jul 11 Jul - 02 Aug 18 Jul - 09 Aug 25 Jul - 16 Aug 01 Aug - 23 Aug 08 Aug - 30 Aug 15 Aug - 06 Sep 22 Aug - 13 Sep 29 Aug - 20 Sep Will these trips run? All our k2 and Gondogoro la treks are guaranteed to run as schedule. Unlike some other companies, our trips will take place with a minimum of 1 person and maximum of 8. Best time to do this Trek Pakistan is blessed with four season weather, spring, summer, autumn and winter. This tour itinerary is involved visiting places where winter is quite harsh yet spring, summer and autumns are very pleasant. We recommend to do this Trek between June and September. Group Prices & discounts We have great range of Couple, Family and Group discounts available, contact us before booking. K2 and Gondogoro trek prices are for the itinerary starting from Islamabad to Skardu K2 - Gondogoro Pass - Hushe Valley and back to Islamabad. -

Thirteen Nations on Mount Everest John Cleare 9

Thirteen nations on Mount Everest John Cleare In Nepal the 1971 pre-monsoon season was notable perhaps for two things, first for the worst weather for some seventy years, and second for the failure of an attempt to realise a long-cherished dream-a Cordee internationale on the top of the world. But was it a complete failure? That the much publicised International Himalayan Expedition failed in its climbing objectives is fact, but despite the ill-informed pronouncements of the headline devouring sceptics, safe in their arm-chairs, those of us who were actually members of the expedition have no doubt that internationally we did not fail. The project has a long history, and my first knowledge of it was on a wet winter's night in 1967 at Rusty Baillie's tiny cottage in the Highlands when John Amatt explained to me the preliminary plans for an international expedi tion. This was initially an Anglo-American-Norwegian effort, but as time went by other climbers came and went and various objectives were considered and rejected. Things started to crystallise when Jimmy Roberts was invited to lead the still-embryo expedition, and it was finally decided that the target should be the great South-west face of Mount Everest. However, unaware of this scheme, Norman Dyhrenfurth, leader of the successful American Everest expedition of 1963-film-maker and veteran Himalayan climber-was also planning an international expedition, and he had actually applied for per mission to attempt the South-west face in November 1967, some time before the final target of the other party had even been decided. -

Catalogue 48: June 2013

Top of the World Books Catalogue 48: June 2013 Mountaineering Fiction. The story of the struggles of a Swiss guide in the French Alps. Neate X134. Pete Schoening Collection – Part 1 Habeler, Peter. The Lonely Victory: Mount Everest ‘78. 1979 Simon & We are most pleased to offer a number of items from the collection of American Schuster, NY, 1st, 8vo, pp.224, 23 color & 50 bw photos, map, white/blue mountaineer Pete Schoening (1927-2004). Pete is best remembered in boards; bookplate Ex Libris Pete Schoening & his name in pencil, dj w/ edge mountaineering circles for performing ‘The Belay’ during the dramatic descent wear, vg-, cloth vg+. #9709, $25.- of K2 by the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. Pete’s heroics The first oxygenless ascent of Everest in 1978 with Messner. This is the US saved six men. However, Pete had many other mountain adventures, before and edition of ‘Everest: Impossible Victory’. Neate H01, SB H01, Yak H06. after K2, including: numerous climbs with Fred Beckey (1948-49), Mount Herrligkoffer, Karl. Nanga Parbat: The Killer Mountain. 1954 Knopf, NY, Saugstad (1st ascent, 1951), Mount Augusta (1st ascent) and King Peak (2nd & 1st, 8vo, pp.xx, 263, viii, 56 bw photos, 6 maps, appendices, blue cloth; book- 3rd ascents, 1952), Gasherburm I/Hidden Peak (1st ascent, 1958), McKinley plate Ex Libris Pete Schoening, dj spine faded, edge wear, vg, cloth bookplate, (1960), Mount Vinson (1st ascent, 1966), Pamirs (1974), Aconcagua (1995), vg. #9744, $35.- Kilimanjaro (1995), Everest (1996), not to mention countless climbs in the Summarizes the early attempts on Nanga Parbat from Mummery in 1895 and Pacific Northwest.