Land Law Subsystems? Urban Vietnam As a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London ***** Publication details: Revisiting the Falklands-Malvinas Question: Transnational and Interdisciplinary Perspectives Edited by Guillermo Mira Delli-Zotti and Fernando Pedrosa https://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/ falklands-malvinas DOI: 10.14296/1220.9781908857804 ***** This edition published in 2021 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-908857-80-4 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses Revisiting the Falklands-Malvinas Question Transnational and Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Guillermo Mira and Fernando Pedrosa INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES Revisiting the Falklands– Malvinas Question Transnational and Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Guillermo Mira and Fernando Pedrosa University of London Press Institute of Latin American Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2021 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/. This book is also available online at http://humanities-digital-library.org. ISBN: 978-1-908857-56-9 (paperback edition) 978-1-908857-85-9 (.epub edition) 978-1-908857-86-6 (.mobi edition) 978-1-908857-80-4 (PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1220.9781908857804 (PDF edition) Institute of Latin American Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House London WC1E 7HU Cover illustration by Marcelo Spotti. -

Joining Our International Movement

WELCOME PACK Joining our international movement If you are reading this it means that you are interested in joining Humanists International The board of Humanists International in August 2018 There are different reasons why your organization should join our international family We have listed these reasons on three levels, from the more abstract motivations to the practical benefits: Common vision Community Benefits COMMON VISION Humanists International is the global representative body of the humanist movement The logo of Humanists International since 2019 Among the international NGOs campaigning for universal human rights, Humanists International is unique as the only global, democratic humanist body We campaign for the right to freedom of thought and expression, for non-discrimination whatever people’s gender, sexuality, or beliefs, and speak out against harmful traditional practices No other organization does what Humanists International does A photo of Amsterdam, the Netherlands We promote the humanist philosophy worldwide, as defined by the official statement of world humanism: the Amsterdam Declaration Humanism is a democratic and ethical lifestance, which affirms that human beings have the right and responsibility to give meaning and shape to their own lives Gulalai Ismail, Board Member of Humanists International We defend humanists at risk of persecution and violence, especially in those countries where apostasy is a crime punishable with either prison or death We work directly with humanists facing verified threats to provide -

Luciana Fazio Supervisors: Maria Elena Cavallaro Giovanni Orsina

1 The Socialist International and the Design of a Community Policy in Latin America During the Late 1970s and 1980s: The Case of Spain and Italy Luciana Fazio Supervisors: Maria Elena Cavallaro Giovanni Orsina LUISS-Guido Carli PhD Program in Politics: History, Theory, Science Cycle XXXII Rome, November 2019 Tesi di dottorato di Luciana Fazio, discussa presso l’Università LUISS, in data 2020. Liberamente riproducibile, in tutto o in parte, con citazione della fonte. Sono comunque fatti salvi i diritti dell’Università LUISS di riproduzione per scopi di ricerca e didattici, con citazione della fonte. 2 Tesi di dottorato di Luciana Fazio, discussa presso l’Università LUISS, in data 2020. Liberamente riproducibile, in tutto o in parte, con citazione della fonte. Sono comunque fatti salvi i diritti dell’Università LUISS di riproduzione per scopi di ricerca e didattici, con citazione della fonte. 3 Acknowledgements I am truly grateful to my supervisors Maria Elena Cavallaro and Giovanni Orsina for their insights and comments to write this thesis. I especially thank all my PhD professors and academics for their support during this process, especially for their advice in terms of literature review and time availability for helping me facing some questions that raised during this process. Special thanks to Professor Joaquin Roy for his support, kindness and hospitality during my visiting exchange program at the University of Miami. Many thanks to the interviewed people (Elena Flores, Luis Yáñez-Barnuevo, Manuel Medina, Beatrice Rangel, Silvio Prado, Juan Antonio Yáñez-Barnuevo, Margherita Boniver, Walter Marossi, Pentti Väänänen, Carlos Parra) for their much needed help to fill the gaps in terms of sources. -

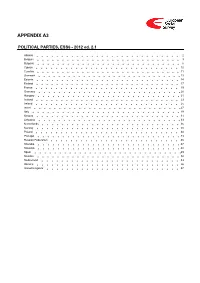

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

SOC IA1I ST I ]IIE R]IAI IO]IA1 Coltgress Re80

Socialist lnternational lnformation No.1/81 SOC IA1I ST I ]IIE R]IAI IO]IA1 coltGRESS re80 ; '11. liF.- - ., ,ri Sr-l.,.$il .- l['':,: l: ' **: u\*- 'L {" \- .,;s[.:ri..:w,ff:r' E I . e &$#. \i; r i;.:i,l;ii 'i l: ::i I "lr : Sodolisl lnlernotionol Congress 1980 Alightin the gloom- T The congress that the socialist International held in Madrid could perhaps be compared to a beacon at a moment when threatening sfrades of darkness werc closing in on the world. when there was little clear sign that the two sup€r-po,wers were willing to come to a rapid and concrete arrangement to halt ihe nuclear arms racefthe congress put forward detailed and realistic measures to halt the suicidal course of rearmament before the world was enveloped in a cataclysm. More than one speaker at the congress made the siniple point, which appears to have escaped the attention of many of the world's strategists, that the stockpiling of hydrogen bombs can scarcely be called a race. A race is supposed to haye a winner and there will be no winners if the world sfumbles into a nuclear war. IVhen many of the richest developed countries were meeting in Madrid at the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe to register the results of the Helsinki declarations, the representatives of powerful political forces from every part of the globe gathered at the Socialist International congress in session a mile away were reaffirming economic and social rights of universal validity. When the blind forces of the market, backed up b5' the sterile ideologies of misguided monetarists, were keeping the developing countries in penury and millions of working people in the developed countries in hopeless unemployment, our congress declared that economics must always haye a human face. -

Global Brain Singularity

VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT BRUSSEL DOCTORAL THESIS GLOBAL BRAIN SINGULARITY Author: Supervisor: Cadell Last Prof. Dr. Francis Heylighen A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies in the ECCO -- Centre Leo Apostel Doctoral School of Human Sciences 1 2 3 Vrije Universiteit Brussel Abstract Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Doctoral School of Human Sciences Global Brain Singularity: Universal history, future evolution and humanity's dialectical horizon By Cadell N. Last ABSTRACT: This work attempts to approach an understanding of global brain singularity through a logical meditation on temporal dynamics of universal process. Global brain singularity is conceived of as a future metasystem of human civilization representing a higher qualitative coherence of order. To better understand the potentiality space of this phenomenon we start with an overview of universal history with the tools of big history and cosmic evolution. These forms of knowledge situate the presence of modern humans in relation to a material complexification from big bang to global civilization. In studying the patterns of complexification throughout universal history, including the evolutionary structure of the physical order, the evolutionary structure of the biological order, and the evolutionary structure of the cultural order, we focus attention on how these patterns may inform reasoned discussion on the contemporary evolution of human society. Human society in the 21st century is struggling to understand the meaning of technological complexification and global convergence but if situated within universal history both processes may be discussed from a fresh perspective. From developing an understanding of universal history for the present moment we shift focus to the structure of historical human metasystems. -

Sexual Exploitation: Prostitution and Organized Crime

2 Sexual Exploitation: Prostitution and Organized Crime Sexual Exploitation: Prostitution and Organized Crime 3 Fondation SCELLES Under the Direction of Yves Charpenel Deputy General Prosecutor of the Supreme Court of France President of the Fondation Scelles Sexual Exploitation Prostitution and Organized Crime ECONOMICA 49, rue Héricart, 75015 Paris 4 Sexual Exploitation: Prostitution and Organized Crime « The proceeds from the sale of this book will be given directly to the Fondation Scelles » Translated from the original French Edition Exploitation sexuelle – Prostitution et crime organisé © Ed. Economica 2012 Translation copyright © Ed. ECONOMICA, 2012 All reproduction, translation, execution and adaptation rights are reserved for all countries Sexual Exploitation: Prostitution and Organized Crime 5 Excerpt from the Dictionary of the French Academy PROSTITUTION n. 13 th century, meaning of "debauchery"; 18 th century, the current meaning. From the Latin prostitutio , "prostitution, desecration." The act of having sexual relations in exchange for payment; activity consisting in practicing regularly such relations. The law does not prohibit prostitution, only soliciting and procuring. Entering into prostitution. A prostitution network. Clandestine, occasional prostitution . ANCIENT MEANING. Sacred prostitution , practiced by the female servants of the goddesses of love or fertility in certain temples and for the profit of these goddesses, in some countries of the Middle East and of the Mediterranean. The Aphrodite temple, in Corinth, -

Reinforcing Participatory Governance Through International Human Rights Obligations of Political Parties

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLH\28-1\hlh104.txt unknown Seq: 1 6-JUL-15 11:17 Reinforcing Participatory Governance Through International Human Rights Obligations of Political Parties Tim Wood* Contemporary human rights law has seen direct international obligations extended to armed groups and businesses. This Article argues that inter- national human rights obligations are crystallizing with respect to a further category of nonstate actor, political parties, albeit only in relation to political participation rights. After briefly examining the largely pro- cedural nature and scope of those rights under international law, this Article surveys existing international and transnational sources of obli- gations of political parties, including both those in power and in opposi- tion. In an effort to buttress these sources and encourage their proliferation, this Article then considers rationales for such obligations, building in part upon the rationales for human rights obligations of businesses and armed groups. Finally, the Article offers some thoughts on possible means of implementing political parties’ emerging international obligations in respect of political participation rights. INTRODUCTION States have traditionally stood alone as subjects of international law. Modern practice and scholarship have extended international legal personal- ity or status, in varying degrees, to international organizations, individuals, armed groups, and businesses.1 Political parties have not figured in this expansionary process, yet they are natural bearers of direct international ob- ligations corresponding to political participation rights—essentially, the rights to vote and to stand in free, periodic elections—as enshrined in all major international human rights instruments, and as discussed further in * LL.B., B.C.L. (McGill), M.I.L. -

ICAPP-2018 Nov

ICAPP-2018 Nov. (5) 10TH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE ICAPP MOSCOW, RUSSIAN FEDERATION, OCTOBER 24-27, 2018 SECRETARIAT OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF ASIAN POLITICAL PARTIES 10th GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE ICAPP MOSCOW, RUSSIAN FEDERATION 24-27 OCTOBER 2018 25 October Opening Ceremony of 10th General Assembly 25 October Opening Ceremony of 10th General Assembly 25 October Plenary Session of 10th General Assembly 25 October 5th Meeting of the ICAPP Women’s Wing 25 October 4th Meeting of the ICAPP Media Forum 25 October 4th Meeting of the ICAPP Youth Wing 26 October 3rd Trilateral Meeting among the ICAPP-COPPPAL-CAPP 26 October Closing Ceremony of the 10th General Assembly of the ICAPP 10th GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE ICAPP MOSCOW, RUSSIAN FEDERATION 24-27 OCTOBER 2018 24 October SC Meeting Table of Contents I. Documents on the 10th General Assembly of the ICAPP 1. Program of the 10th General Assembly ····················································· 3 2. Program of the 4th Meeting of the ICAPP Media Forum ································ 5 3. Program of the 5 th Meeting of the ICAPP Women’s Wing ····························· 6 4. Program of the 4 th Meeting of the ICAPP Youth Wing ································· 7 5. Program of the 3 rd Trilateral Meeting among the ICAPP-COPPPAL-CAPP ········· 8 6. List of Participants in the 10th General Assembly ········································ 9 7. List of Candidates for the Bureau of the 10th General Assembly ·····················21 8. Conference Procedures for the 10th General Assembly ································23 9. Moscow Declaration ·········································································25 10. Moscow Statement for the 4 th Meeting of the ICAPP Media Forum ·················32 11. Moscow Statement for the 5 th Meeting of the ICAPP Women’s Wing ···············35 12. -

Singularity! Communism! Apocalypse!

Last Singularity! Communism! Apocalypse! Cadell Last, Global Brain Institute (GBI) Singularity! Communism! Apocalypse!: An Exploration. ! ABSTRACT: This article is first developed by exploring contemporary so- ciotechnological Singularity theories (most notably the utopian notions of computer scientist Ray Kurzweil and cyberneticist Francis Heylighen). Secondly, this article is de- veloped by exploring historical theories of collective human development inspired by German Idealism (most notably the utopian notions of Georg Hegel and Karl Marx). In relation to these idealistic and utopian notional structures, this article then presents an overview of emerging common problems and tensions related to 21st century geopoli- tics and socioeconomics. This section is presented with the perspective that humanity is approaching a systemically immanent zero-level (apocalypse!) that can only be avoid- ed via the mediation of a fundamental metasystem transition towards a new commons global order structured within distributed egalitarian networks. The evental becoming- space between possible systemic collapse and general idealistic attractor state is what I refer to as the “Commons Gap”: a space which may be navigable with a materialist dia- lectic that affirms humanist universality in diversity. Finally, I conclude with a compara- tive reflection on theories of eschatological capitalism (end times capitalism) — Kurzweilian vs. Marxist — in relation to the increasing openness and ambiguity of the human situation vis-a-vis global capitalism and sociotechnological evolution. Although both the Kurzweilian and Marxist capitalist end times visions are almost certainly incor- rect, they both provide us with interesting thought space to contemplate the necessity for humanity to discover a new level of common agency with a new level of distributed organization. -

Cytvol35n1.Pdf

© 2011, Fundação Joaquim Nabuco Todos os direitos reservados, proibida a reprodução por meios eletrônicos, fotográficos, gravação ou quaisquer outros, sem permissão por escrito da Fundação Joaquim Nabuco. E-mail: [email protected] http://www.fundaj.gov.br Pede-se permuta On demande l’ échange We ask for exchange Pidese permuta Si richiede lo scambio Man bittet um Austausch Intershangho dezirata Diagramação: Denise Simões - EDUFPE Edson de Araújo Nunes Revisão linguística: Solange Carvalho, Maria Eduarda Alencar e Gabriela Medeiros Projeto da capa: Editora Massangana Ilustração da capa: Mapa cedido por Alexandrina Sobreira, de seu acervo pessoal Ciência & Trópico - Recife: Fundação Joaquim Nabuco 1973 - Semestral Continuação do Boletim do Instituto Joaquim Nabuco de Pesquisas Sociais (v.35-1), 1952-1971. A partir do volume 8 que corresponde ao ano de 1980, o Instituto Joaquim Nabuco de Pesquisas Sociais passou a se denominar Fundação Joaquim Nabuco. ISSN 0304-2685 CDU 3: 061.6(05) APRESENTAÇÃO Os artigos incluídos nos três volumes da Revista Ciência & Trópico foram feitos na Quinta Escola de Verão Sul-Sul cuja temática focalizou Repensar o Desenvolvimento: Alternativas Regionais e Globais para o Desenvolvimento no Sul, que ocorreu no Recife, em maio de 2012, no contexto do Programa de Colaboração Acadêmica entre África, América Latina e Ásia. A Escola de Verão, coordenada pela Associação de Estudos Políticos e Internacionais da Ásia (Apisa), pelo Conselho Latinoamericano de Ciências Sociais (Clacso) e pelo Conselho para o Desenvolvimento da Pesquisa em Ciências Sociais da África (Codesria), e, com o aval da Agência Sueca para o Desenvolvimento e a Cooperação Internacional (Asdi), foi organizada conjuntamente com a Fundação Joaquim Nabuco (Fundaj). -

Hivos Annual Report 2006

HIVOS ANNUAL REPORT 2006 HIVOS ANNUAL REPORT 2006 4 | HIVOS ANNUAL REPORT 2006 Missie Roles Hivos is a Dutch non-governmental organisation whose work is based Hivos strengthens local organisations with funds, knowledge and on humanist values. Together with local civil society organisations in contacts. Hivos itself lobbies at a Dutch, European and global level, developing countries Hivos wants to contribute to the creation of a free, and acts as a player in local civil society through its Regional Offices. fair and sustainable world: a world in which citizens – women and men – Hivos also stimulates the generation, exchange and application of have equal access to resources and opportunities for development. In knowledge for development. As a participant in coalitions and a contact which they are able to take an active and equal part in the decison- broker, Hivos is part of a large number of networks. making processes which determine their lives, their society and their future. Themes Hivos’ activities include: Hivos believes in people’s creativity and capability. In its organisation Sustainable Economic Development philosophy quality, cooperation and renewal are core concepts. Hivos Democratisation, Rights, Aids and Gender feels connected to the poor and marginalised in Africa, Asia, Latin Culture, ICT and Media America and Southeastern Europe. A sustainable improvement in their situation is the ultimate benchmark for the work and effort put forth by Cooperation Hivos. An important theme throughout is the strengthening of the Hivos collaborates with numerous non-governmental organisations position of women. (NGOs) and other civil society organisations, businesses and govern- ments in the Netherlands, Europe and in the South.