Nihilism Incorporated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terms for Talking About Information and Communication

Information 2012, 3, 351-371; doi:10.3390/info3030351 OPEN ACCESS information ISSN 2078-2489 www.mdpi.com/journal/information Concept Paper Terms for Talking about Information and Communication Corey Anton School of Communications, Grand Valley State University, 210 Lake Superior Hall, Allendale, MI 49401, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-616-331-3668; Fax: +1-616-331-2700 Received: 4 June 2012; in revised form: 17 August 2012 / Accepted: 20 August 2012 / Published: 27 August 2012 Abstract: This paper offers terms for talking about information and how it relates to both matter-energy and communication, by: (1) Identifying three different levels of signs: Index, based in contiguity, icon, based in similarity, and symbol, based in convention; (2) examining three kinds of coding: Analogic differences, which deal with positive quantities having contiguous and continuous values, and digital distinctions, which include “either/or functions”, discrete values, and capacities for negation, decontextualization, and abstract concept-transfer, and finally, iconic coding, which incorporates both analogic differences and digital distinctions; and (3) differentiating between “information theoretic” orientations (which deal with data, what is “given as meaningful” according to selections and combinations within “contexts of choice”) and “communication theoretic” ones (which deal with capta, what is “taken as meaningful” according to various “choices of context”). Finally, a brief envoi reflects on how information broadly construed relates to probability and entropy. Keywords: sign; index; icon; symbol; coding; context; information; communication “If you have an apple and I have an apple and we exchange apples then you and I will still each have one apple. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 18 August 2015

United Nations A/70/194 General Assembly Distr.: General 18 August 2015 Original: English Seventieth session Request for the inclusion of a supplementary item in the agenda of the seventieth session Observer status for the International Conference of Asian Political Parties in the General Assembly Letter dated 11 August 2015 from the representatives of Australia, Cambodia, Japan, Nepal, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea and Sri Lanka to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General We, the undersigned, have the honour to request, in accordance with rule 14 of the rules of procedure of the General Assembly, the inclusion in the agenda of the seventieth session of the General Assembly a supplementary item entitled “Observer status for the International Conference of Asian Political Parties in the General Assembly”. The International Conference of Asian Political Parties (ICAPP) was launched in Manila, the Philippines, in September 2000 to build bridges of political cooperation and to establish networks of mutual benefit among mainstream political parties in Asia, both ruling and in opposition. Over its first decade, ICAPP has grown steadily in both membership and influence. As of June 2015, ICAPP ’s membership has reached more than 360 eligible political parties in 52 States and 1 territory in Asia. After establishing fraternal linkages and cooperation with the Permanent Conference of Political Parties in Latin America and the Caribbean (COPPPAL) in 2008, ICAPP has also been undertaking efforts to reach out to the political parties in other continents, and successfully helped political parties in Africa establish the Council of African Political Parties (CAPP) in 2013. -

Opportunities and Pitfalls in International Cooperation: Lessons

Henschke, J. A. "Opportunities and Pitfalls in International Cooperation: Lessons Learned in the Cooperative Development of Lifelong Learning Strategies of an US and South African University." In Comparative Adult Education 2008: Experiences and Examples. Studies in pedagogy, Andragogy, and Gerontagogy. Vol. 61. Reischmann, J., and Bron, M. [Eds]. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang. Pp. 127-140, 2008. I STUDIES Jost Reischmann IN PEDAGOGY, Michal Bron jr ANDRAGOGY, AND GERONTAGOGY (eds.) Edited by Franz Poggeler Comparative Vol. 61 Adult Education 2008 Experiences and Examples A Publication ofthe International Society for Comparative Adult Education ISCAE £ £ PETER LANG PETER LANG Frankfurt am Main· Berlin· Bern· Bruxelles . New York· Oxford· Wien Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche N ationalbibliothek Table of Contents The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at <http://www.d-nb.de>. Jost Reischmann & Michal Bron Jr (Germany / Sweden): Introduction ...................................................................................................... 9 A. Comparative Adult Education: Developments aud Potentials Jost Reischmann (Germany): Comparative Adult Education: Arguments, Typology, Difficulties .............. 19 Mark Bray (UNESCO-IIEP, France): The Multifaceted Field ofComparative Education: Evolution, Themes, Actors, and Applications ............................................................................... -

Download Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS AN NUAL RE PORT JULY 1, 2003-JUNE 30, 2004 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 434-9800 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail [email protected] OFFICERS and DIRECTORS 2004-2005 OFFICERS DIRECTORS Term Expiring 2009 Peter G. Peterson* Term Expiring 2005 Madeleine K. Albright Chairman of the Board Jessica P Einhorn Richard N. Fostert Carla A. Hills* Louis V Gerstner Jr. Maurice R. Greenbergt Vice Chairman Carla A. Hills*t Robert E. Rubin George J. Mitchell Vice Chairman Robert E. Rubin Joseph S. Nye Jr. Richard N. Haass Warren B. Rudman Fareed Zakaria President Andrew Young Michael R Peters Richard N. Haass ex officio Executive Vice President Term Expiring 2006 Janice L. Murray Jeffrey L. Bewkes Senior Vice President OFFICERS AND and Treasurer Henry S. Bienen DIRECTORS, EMERITUS David Kellogg Lee Cullum AND HONORARY Senior Vice President, Corporate Richard C. Holbrooke Leslie H. Gelb Affairs, and Publisher Joan E. Spero President Emeritus Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, Vin Weber Maurice R. Greenberg Honorary Vice Chairman National Program and Academic Outreach Term Expiring 2007 Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Elise Carlson Lewis Fouad Ajami Director Emeritus Vice President, Membership David Rockefeller Kenneth M. Duberstein and Fellowship Affairs Honorary Chairman Ronald L. Olson James M. Lindsay Robert A. Scalapino Vice President, Director of Peter G. Peterson* t Director Emeritus Studies, Maurice R. Creenberg Chair Lhomas R. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

G.K.Chesterton- Heretics

HERETICS by Gilbert K. Chesterton "To My Father" Source Heretics was copyrighted in 1905 by the John Lane Company. This electronic text is derived from the twelth (1919) edition published by the John Lane Company of New York City and printed by the Plimpton Press of Norwood, Massachusetts. The text carefully follows that of the published edition (including British spelling). The Author Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in London, England on the 29th of May, 1874. Though he considered himself a mere "rollicking journalist," he was actually a prolific and gifted writer in virtually every area of literature. A man of strong opinions and enormously talented at defending them, his exuberant personality nevertheless allowed him to maintain warm friendships with people--such as George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells--with whom he vehemently disagreed. Chesterton had no difficulty standing up for what he believed. He was one of the few journalists to oppose the Boer War. His 1922 "Eugenics and Other Evils" attacked what was at that time the most progressive of all ideas, the idea that the human race could and should breed a superior version of itself. In the Nazi experience, history demonstrated the wisdom of his once "reactionary" views. His poetry runs the gamut from the comic 1908 "On Running After One's Hat" to dark and serious ballads. During the dark days of 1940, when Britain stood virtually alone against the armed might of Nazi Germany, these lines from his 1911 Ballad of the White Horse were often quoted: I tell you naught for your comfort, Yea, naught for your desire, Save that the sky grows darker yet And the sea rises higher. -

The Kennedy Administration's Alliance for Progress and the Burdens Of

The Kennedy Administration’s Alliance for Progress and the Burdens of the Marshall Plan Christopher Hickman Latin America is irrevocably committed to the quest for modernization.1 The Marshall Plan was, and the Alliance is, a joint enterprise undertaken by a group of nations with a common cultural heritage, a common opposition to communism and a strong community of interest in the specific goals of the program.2 History is more a storehouse of caveats than of patented remedies for the ills of mankind.3 The United States and its Marshall Plan (1948–1952), or European Recovery Program (ERP), helped create sturdy Cold War partners through the economic rebuilding of Europe. The Marshall Plan, even as mere symbol and sign of U.S. commitment, had a crucial role in re-vitalizing war-torn Europe and in capturing the allegiance of prospective allies. Instituting and carrying out the European recovery mea- sures involved, as Dean Acheson put it, “ac- tion in truly heroic mold.”4 The Marshall Plan quickly became, in every way, a paradigmatic “counter-force” George Kennan had requested in his influential July 1947 Foreign Affairs ar- President John F. Kennedy announces the ticle. Few historians would disagree with the Alliance for Progress on March 13, 1961. Christopher Hickman is a visiting assistant professor of history at the University of North Florida. I presented an earlier version of this paper at the 2008 Policy History Conference in St. Louis, Missouri. I appreciate the feedback of panel chair and panel commentator Robert McMahon of The Ohio State University. I also benefited from the kind financial assistance of the John F. -

Philippine Journal of Public Administra Tion

PHILIPPINE JOURNAL OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION JANUARY-DECEMBER 2010 VOL. LIV NOS. 1&2 NOS. LIV VOL. 2010 JANUARY-DECEMBER ADMINISTRATION PUBLIC OF JOURNAL PHILIPPINE VOLUME LIVVOLUME JANUARY-DECEMBER 2010 NUMBERS 1 & 2 Hernandez Caraan Florano Co Reyes & Fernandez Brillantes Jr. Ocampo Grossmann Prakash Quah & Eun Sil Kim Kim Young Jong Ligthart of the Philippines Diliman, Association Schools Public Administration in Philippines, PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Journal of the National College Public Administration and Governance, University PHILIPPINE JOURNAL and the Philippine Society for Public Administration Accountability in Aid Management A Proposed Integrity Model in the Administration of Labor Justice Institutionalizing Reforms through the Citizens Report Card The Long and Winding Road to Infrastructure Development Reform Corruption, Contradiction and Conscience : A Whistleblower’s Story A Reform Framework for Good Governance: Focus on Anti-Corruption Wicked Problems, Government Failures: Corruption and Lesser Evils Civil Society Anti-Corruption Efforts: The Case of Ukraine and the Philippines Role of Civil Society in Managing Anti-Corruption-Initiatives India Curbing Corruption in the Philippines: Is this an Impossible Dream? of Corruption Toward Improving the Quality of Life Through Controlling Culture An Overview of East Asian Anti-Corruption Research and Applications OF OVERVIEWPhilippine OF EAST Journal ASIAN of AC Public RESEARCH Administration, AND APPLICATIONS Vol. LIV Nos. 1-2 (Jan.-December 2010) 1 Whatever You Do, Never Use The C Word: an Overview of East Asian Anti-Corruption Research and Ap- plications MICHAEL LIGTHART * This article takes stock of 40 years of anti-corruption (AC) research & practices, the progress made and challenges ahead. It takes an East Asia tour, thus carving out the pre-conditions for effective Anti-Corruption Agencies. -

An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff Kentucky Mountain Bible College

Inklings Forever Volume 5 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fifth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Lewis & Article 14 Friends 6-2006 An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff Kentucky Mountain Bible College Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Huff, Randy (2006) "An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton," Inklings Forever: Vol. 5 , Article 14. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol5/iss1/14 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume V A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fifth FRANCES WHITE COLLOQUIUM on C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2006 Upland, Indiana An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff Huff, Randy. “An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton.” Inklings Forever 5 (2006) www.taylor.edu/cslewis An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff G.K. Chesterton was regarded by friend and foe as he enters, it is built wrong.”6 In the conclusion to a man of genius, a defender of the faith, a debater and What’s Wrong with the World, he sums it up thus: conversationalist par excellence. -

History 598, Fall 2004

Meeting Time: The seminar will meet Tuesday afternoons, 1:30-4:30, in Dickinson 211 Week I (9/14) Introduction: Jeremy Campbell, Grammatical Man Evelyn Fox Keller, Refiguring Life: Metaphors of Twentieth-Century Biology Questions and Themes Secondary Lily E. Kay, "Cybernetics, Information, Life: The Emergence of Scriptural Representations of Heredity", Configurations 5(1997), 23-91 [PU online]; and "Who Wrote the Book of Life? Information and the Transformation of Molecular Biology," Week II (9/21) Science in Context 8 (1995): 609-34. Michael S. Mahoney, "Cybernetics and Information Technology," in Companion to the The Discursive History of Modern Science, ed. R. C. Olby et al., Chap.34 [online] Rupture Karl L. Wildes and Nilo A. Lindgren, A Century of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, 1882-1982, Parts III and IV (cf. treatment of some of the Report: Philipp v. same developments in David Mindell, Between Humans and Machines) Hilgers James Phinney Baxter, Scientists Against Time Supplementary John M.Ellis, Against Deconstruction (Princeton, 1989), Chaps. 2-3 Daniel Chandler, "Semiotics for Beginners" Primary [read for overall structure before digging in to the extent you can] Week III (9/28) Warren S. McCulloch and Walter Pitts, "A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity", Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 5(1943), 115-33; repr. in Machines and Warren S. McCulloch, Embodiments of Mind (MIT, 1965), 19-39, and in Margaret A. Nervous Systems Boden (ed.), The Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence (Oxford, 1990), 22-39. Alan M. Turing, "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to Report: Perrin the Entscheidungsproblem", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, ser. -

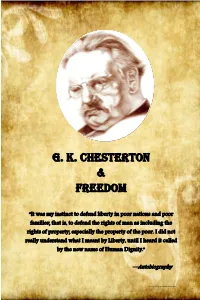

It Was My Instinct to Defend Liberty in Poor Nations and Poor Families; That Is, to Defend the Rights of Man As Including

G. K. Chesterton & G. K.Freedom Chesterton “It was my instinct to defend liberty in poor nations and poor families; that is, to defend the rights of man as including the rights of property; especially the property of the poor. I did not really understand what I meant by Liberty, until I heard it called by the new name of Human Dignity.” —Autobiography © 2012 G. K. Chesterton Institute for Faith & Culture “The free man owns himself. He can damage himself with either eating or drinking; he can ruin himself with gambling. If he does, he is certainly a damn fool, and he might possibly be a damned soul; but if he may not, he is not a free man any more than a dog.” —Broadcast talk, June 1935 “Most modern freedom is at root fear. It is not so much that we are too bold to en- dure rules; it is rather that we are too timid to endure responsibilities.” —What’s Wrong With the World G. K. Chesterton “The man of the true religious tradition understands two things: liberty and obedience. The first means knowing what you really want. The second means knowing what you really trust.” —G. K.’s Weekly, August 18, 1933 © 2012 G. K. Chesterton Institute for Faith & Culture Fr. Ian Boyd on Chesterton & Freedom “The two ideas upon which Christian theology was based were the ideas of Reason and Liberty.” So said Chesterton in November 1911 in his address to a meeting at Cambridge organized by a student club who called themselves “The Heretics.” He went on to say that Reason was real. -

Information Theory." Traditions of Systems Theory: Major Figures and Contemporary Developments

1 Do not cite. The published version of this essay is available here: Schweighauser, Philipp. "The Persistence of Information Theory." Traditions of Systems Theory: Major Figures and Contemporary Developments. Ed. Darrell P. Arnold. New York: Routledge, 2014. 21-44. See https://www.routledge.com/Traditions-of-Systems-Theory-Major-Figures-and- Contemporary-Developments/Arnold/p/book/9780415843898 Prof. Dr. Philipp Schweighauser Department of English University of Basel Nadelberg 6 4051 Basel Switzerland Information Theory When Claude E. Shannon published "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" in 1948, he could not foresee what enormous impact his findings would have on a wide variety of fields, including engineering, physics, genetics, cryptology, computer science, statistics, economics, psychology, linguistics, philosophy, and aesthetics.1 Indeed, when he learned of the scope of that impact, he was somewhat less than enthusiastic, warning his readers in "The Bandwagon" (1956) that, while "many of the concepts of information theory will prove useful in these other fields, [...] the establishing of such applications is not a trivial matter of translating words to a new domain, but rather the slow tedious process of hypothesis and experimental verification" (Shannon 1956, 3). For the author of this essay as well as my fellow contributors from the humanities and social sciences, Shannon's caveat has special pertinence. This is so because we get our understanding of information theory less from the highly technical "A Mathematical Theory