Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corruption of the Characters in Willa Cather's a Lost Lady

Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8435 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.51, 2018 Corruption of the Characters in Willa Cather’s A Lost Lady Dewi Nurnani Puppetry Department, Faculty of Performing Arts, Indonesia Institute of Arts, Surakarta, Central Java, Indonesia, 57126 email: [email protected] Abstract This writing studies about corruption of the characters in the novel entitled A Lost Lady by Willa Cather. The mimetic approach is used to analyze this novel. So in creating art, an author is much influenced by the social condition of society in which he lives or creates, directly or indirectly. It can be learned that progression does not always make people happy but often it brings difficulties and even disaster in their lives. It is also found that the corruption in the new society happens because the characters are unable to endure their passionate nature as well as to adapt with the changing.To anticipate the changing, one must have a strong mentality among other things, by religion or a good education in order that he does not fall into such corruption as the characters in A Lost Lady . Keywords : corruption, ambition, passionate, new values, old values 1. Background of The Study Willa Sibert Cather, an American novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist, and poet, was born on December 7, 1983 near Winchester, Virginia, in the fourth generation of an Anglo-Irish family. Her father, Charles F. Cather, and her mother, Mary Virginia Cather, and also their family moved to the town of red Cloud, Nebraska, when she was nine years old. -

If You Like My Ántonia, Check These Out!

If you like My Ántonia, check these out! This event is part of The Big Read, an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with the Institute of Museum and Library Services and Arts Midwest. Other Books by Cather About Willa Cather Alexander's Bridge (CAT) Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice Cather's first novel is a charming period piece, a love by Sharon O'Brien (920 CATHER, W.) story, and a fatalistic fable about a doomed love affair and the lives it destroys. Willa Cather: A Literary Life by James Leslie Woodress (920 CATHER, W.) Death Comes for the Archbishop (CAT) Cather's best-known novel recounts a life lived simply Willa Cather: The Writer and her World in the silence of the southwestern desert. by Janis P. Stout (920 CATHER, W.) A Lost Lady (CAT) Willa Cather: The Road is All This Cather classic depicts the encroachment of the (920 DVD CATHER, W.) civilization that supplanted the pioneer spirit of Nebraska's frontier. My Mortal Enemy (CAT) First published in 1926, this is Cather's sparest and most dramatic novel, a dark and oddly prescient portrait of a marriage that subverts our oldest notions about the nature of happiness and the sanctity of the hearth. One of Ours (CAT) Alienated from his parents and rejected by his wife, Claude Wheeler finally finds his destiny on the bloody battlefields of World War I. O Pioneers! (CAT) Willa Cather's second novel, a timeless tale of a strong pioneer woman facing great challenges, shines a light on the immigrant experience. -

Willa Cather and American Arts Communities

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2004 At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jewell, Andrew W., "At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 15. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES by Andrew W. Jewel1 A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Susan J. Rosowski Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2004 DISSERTATION TITLE 1ather and Ameri.can Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewel 1 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Approved Date Susan J. Rosowski Typed Name f7 Signature Kenneth M. Price Typed Name Signature Susan Be1 asco Typed Name Typed Nnme -- Signature Typed Nnme Signature Typed Name GRADUATE COLLEGE AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES Andrew Wade Jewell, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2004 Adviser: Susan J. -

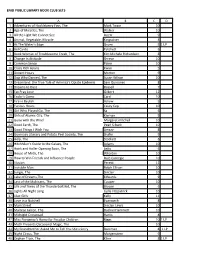

Web Book Club Sets

ENID PUBLIC LIBRARY BOOK CLUB SETS A B C D 1 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Mark Twain 10 2 Age of Miracles, The Walker 10 3 All the Light We Cannot See Doerr 9 4 Animal, Vegetable, Miracle Kingsolver 4 5 At The Water's Edge Gruen 5 1 LP 6 Bel Canto Patchett 6 7 Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, The Kim Michele Richardson 8 8 Change in Attitude Shreve 10 9 Common Sense Paine 10 10 Crazy Rich Asians Kwan 5 11 Distant Hours Morton 9 12 Dog Who Danced, The Susan Wilson 10 13 Dreamland: the True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic Sam Quinones 8 14 Dreams to Dust Russell 7 15 Eat Pray Love Gilbert 12 16 Ender's Game Card 10 17 Fire in Beulah Askew 5 18 Furious Hours Casey Cep 10 19 Girl Who Played Go, The Sa 6 20 Girls of Atomic City, The Kiernan 9 21 Gone with the Wind Margaret mitchell 10 22 Good Earth, The Pearl S Buck 10 23 Good Things I Wish You Amsay 8 24 Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, The Shafer 9 25 Help, The Stockett 6 26 Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, The Adams 10 27 Honk and Holler Opening Soon, The Letts 6 28 House of Mirth, The Wharton 10 29 How to Win Friends and Influence People Dale Carnegie 10 30 Illusion Peretti 12 31 Invisible Man Ralph Ellison 10 32 Jungle, The Sinclair 10 33 Lake of Dreams,The Edwards 9 34 Last of the Mohicans, The Cooper 10 35 Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, The Bryson 6 36 Lights All Night Long Lydia Fitzpatrick 10 37 Lilac Girls Kelly 11 38 Love in a Nutshell Evanovich 8 39 Main Street Sinclair Lewis 10 40 Maltese Falcon, The Dashiel Hammett 10 41 Midnight Crossroad Harris 8 -

Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Newsletter VOLUME Xxxlv, No

Copyright © 1990 by the Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial and Educational Foundation ISSN 0197-663X Fall, 1990 Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Newsletter VOLUME XXXlV, No. 3 Literary Annual RED CLOUD, NEBRASKA Death Comes for the Archbishop: what as she used the statue of the Auvergnat Bishop Lamy A Map of Intersecting Worlds which inspired her. Evelyn Hailer, Doane College Clearly, "the life-size bronze" In her invocation of God’s or genre clusters relate to and statue before St. Francis ca- plenitude -- "He takes all reinforce each other because thedral became a monumental forces, all space, all time to fill she found a subject ideally bronze, if not a colossus, in her them with universes of beauty" suited to her interests and her imagination. It was "something ("Moral Music" 178) --Willa technique. fearless and fine and very, very Cather anticipated a model that The first of these genre well-bred m something that she herself used in writing visions is Franco-centric and spoke of race" ("On DCA" 7) -- Death Comes for the Arch- qualified by apologetic bio- that the statue communicated to bishop. She achieved credibility graphical tracts. The second her that inspired her to structure in this narrative, as she pre- medieval and characterized by her "biography" of Bishop Lamy ferred to call it, by invoking the iconography and hagiography. toward heroic myth. A visual rules of a variety of genres The third, Mexican, contains disparity between Lamy the which provide differing visions elements such as folklore, the bronze statue and Lamy the man of the cosmos -- a term more tall tale, the ballad of violence becomes clear when one com- accurate in this instance than and sex -- all anticipatory of pares the three-dimensional "world views." By juxtaposi- magic realism. -

UNIVERSITY of $ASKATCHEWAN This Volume Is The

UNIVERSITY OF $ASKATCHEWAN This volume is the property of the University of Saskatchewan, and the Itt.rory rights of the author and of the University must be respected. If the reader ob tains any assistance from this volume, he must give proper credit in his ownworkr This Thesis by . EJi n.o r • C '.B • C j-IEJ- S0 M has been used by the following persons, whose slgnature~ attest their acc;eptance of the above restri ctions . Name and Address Date , UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN The Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Saskatchewan. We, the undersigned members of the Committee appointed by you to examine the Thesis submitted by Elinor C. B. Chelsom, B.A., B;Ed., in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts, beg to report that we consider the thesis satisfactory both in form and content. Subject of Thesis: ttWilla Cather And The Search For Identity" We also report that she has successfully passed an oral examination on the general field of the subject of the thesis. 14 April, 1966 WILLA CATHER AND THE SEARCH FOR IDENTITY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Mas ter of Arts in the Department of English University of Saskatchewan by Elinor C. B. Chelsom Saskatoon, Saskatchewan April, 1966 Copyrigh t , 1966 Elinor C. B. Chelsom IY 1 s 1986 1 gratefully acknowledge the wise and encouraging counsel of Carlyle King, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. my supervisor in the preparation of this thesis. -

Willa Cather and the Swedes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Fall 1984 Willa Cather And The Swedes Mona Pers University College at Vasteras Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Pers, Mona, "Willa Cather And The Swedes" (1984). Great Plains Quarterly. 1756. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1756 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WILLA CATHER AND THE SWEDES MONAPERS Willa Cather's immigrant characters, almost a able exaggeration when in 1921 she maintained literary anomaly at the time she created them, that "now all Miss Cather's books have been earned her widespread critical and popular ac translated into the Scandinavian," the Swedish claim, not least in the Scandinavian countries, a translations of 0 Pioneers! and The Song of market she was already eager to explore at the the Lark whetted the Scandinavian appetite beginning of her literary career. Sweden, the for more Cather. As the 1920s drew to a close, first Scandinavian country to "discover" her her reputation grew slowly but steadily. Her books, issued more translations of Cather fic friend George Seibel was probably guilty of tion than any other European country. In considerably less exaggeration than was Eva fact, Sweden was ten years ahead of any other Mahoney when he recalled "mentioning her Scandinavian country in publishing the transla name in the Gyldendal Boghandel in Copen tion of a Cather novel (see table). -

EMPIRICAL TESTS of COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION Christopher Buccafusco† & Paul J

0001-0044_BUCCAFUSCO_081313_WEB (DO NOT DELETE) 8/13/2013 4:50 PM DO BAD THINGS HAPPEN WHEN WORKS ENTER THE PUBLIC DOMAIN?: EMPIRICAL TESTS OF COPYRIGHT TERM EXTENSION Christopher Buccafusco† & Paul J. Heald †† ABSTRACT According to the current copyright statute, copyrighted works of music, film, and literature will begin to transition into the public domain in 2018. While this will prove a boon for users and creators, it could be disastrous for the owners of these valuable copyrights. Therefore, the next few years will likely witness another round of aggressive lobbying by the film, music, and publishing industries to extend the terms of already-existing works. These industries, and a number of prominent scholars, claim that when works enter the public domain, bad things will happen to them. They worry that works in the public domain will be underused, overused, or tarnished in ways that will undermine the works’ economic and cultural value. Although the validity of their assertions turns on empirically testable hypotheses, very little effort has been made to study them. This Article attempts to fill that gap by studying the market for audiobook recordings of bestselling novels, a multi-million dollar industry. Data from this study, which includes a novel human-subjects experiment, suggest that term-extension proponents’ claims about the public domain are suspect. Audiobooks made from public domain bestsellers (1913–22) are significantly more available than those made from copyrighted bestsellers (1923–32). In addition, the experimental evidence suggests that professionally made recordings of public domain and copyrighted books are of similar quality. Finally, while a low quality recording seems to lower a listener’s valuation of the underlying work, the data do not suggest any correlation between that valuation and the legal status of the underlying work. -

Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory

Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory Edited by William E. Cain Professor of English Wellesley College A Routledge Series 94992-Humphries 1_24.indd 1 1/25/2006 4:42:08 PM Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory William E. Cain, General Editor Vital Contact Negotiating Copyright Downclassing Journeys in American Literature Authorship and the Discourse of from Herman Melville to Richard Wright Literary Property Rights in Patrick Chura Nineteenth-Century America Martin T. Buinicki Cosmopolitan Fictions Ethics, Politics, and Global Change in the “Foreign Bodies” Works of Kazuo Ishiguro, Michael Ondaatje, Trauma, Corporeality, and Textuality in Jamaica Kincaid, and J. M. Coetzee Contemporary American Culture Katherine Stanton Laura Di Prete Outsider Citizens Overheard Voices The Remaking of Postwar Identity in Wright, Address and Subjectivity in Postmodern Beauvoir, and Baldwin American Poetry Sarah Relyea Ann Keniston An Ethics of Becoming Museum Mediations Configurations of Feminine Subjectivity in Jane Reframing Ekphrasis in Contemporary Austen, Charlotte Brontë, and George Eliot American Poetry Sonjeong Cho Barbara K. Fischer Narrative Desire and Historical The Politics of Melancholy from Reparations Spenser to Milton A. S. Byatt, Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie Adam H. Kitzes Tim S. Gauthier Urban Revelations Nihilism and the Sublime Postmodern Images of Ruin in the American City, The (Hi)Story of a Difficult Relationship from 1790–1860 Romanticism to Postmodernism Donald J. McNutt Will Slocombe Postmodernism and Its Others Depression Glass The Fiction of Ishmael Reed, Kathy Acker, Documentary Photography and the Medium and Don DeLillo of the Camera Eye in Charles Reznikoff, Jeffrey Ebbesen George Oppen, and William Carlos Williams Monique Claire Vescia Different Dispatches Journalism in American Modernist Prose Fatal News David T. -

Banned & Challenged Classics

26. Gone with the Wind, 26. Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell by Margaret Mitchell 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright Banned & Banned & 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Challenged Challenged by Ken Kesey by Ken Kesey 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, Classics Classics by Kurt Vonnegut by Kurt Vonnegut 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway by Ernest Hemingway 33. The Call of the Wild, 33. The Call of the Wild, The titles below represent banned or The titles below represent banned or by Jack London by Jack London challenged books on the Radcliffe challenged books on the Radcliffe 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of by James Baldwin by James Baldwin the 20th Century list: the 20th Century list: 38. All the King's Men, 38. All the King's Men, 1. The Great Gatsby, 1. The Great Gatsby, by Robert Penn Warren by Robert Penn Warren by F. Scott Fitzgerald by F. Scott Fitzgerald 40. The Lord of the Rings, 40. The Lord of the Rings, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.D. Salinger by J.D. Salinger 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 3. The Grapes of Wrath, 3. -

REVIEW Volume 60 Z No

REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 Winter 2018 My Ántonia at 100 Willa Cather REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 | Winter 2018 28 35 2 15 22 CONTENTS 1 Letters from the Executive Director, the President 20 Reading My Ántonia Gave My Life a New Roadmap and the Editor Nancy Selvaggio Picchi 2 Sharing Ántonia: A Granddaughter’s Purpose 22 My Grandmother—My Ántonia z Kent Pavelka Tracy Sanford Tucker z Daryl W. Palmer 23 Growing Up with My Ántonia z Fritz Mountford 10 Nebraska, France, Bohemia: “What a Little Circle Man’s My Ántonia, My Grandparents, and Me z Ashley Nolan Olson Experience Is” z Stéphanie Durrans 24 24 Reflection onMy Ántonia z Ann M. Ryan 10 Walking into My Ántonia . z Betty Kort 25 Red Cloud, Then and Now z Amy Springer 11 Talking Ántonia z Marilee Lindemann 26 Libby Larsen’s My Ántonia (2000) z Jane Dressler 12 Farms and Wilderness . and Family z Aisling McDermott 27 How I Met Willa Cather and Her My Ántonia z Petr Just 13 Cather in the Classroom z William Anderson 28 An Immigrant on Immigrants z Richard Norton Smith 14 Each Time, Something New to Love z Trish Schreiber 29 My Two Ántonias z Evelyn Funda 14 Our Reflections onMy Ántonia: A Family Perspective John Cather Ickis z Margaret Ickis Fernbacher 30 Pioneer Days in Webster County z Priscilla Hollingshead 15 Looking Back at My Ántonia z Sharon O’Brien 31 Growing Up in the World of Willa Cather z Kay Hunter Stahly 16 My Ántonia and the Power of Place z Jarrod McCartney 32 “Selah” z Kirsten Frazelle 17 My Ántonia, the Scholarly Edition, and Me z Kari A. -

Review Red Cloud, Nebraska 68970 Summer, 1999 Telephone (402) 746-2653

Copyright © 1999 by the Willa Cather Roneer ISSN 0197-663X Memorial and Educational Foundation (The Wil~ Cather Society) Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Newsletter and ~0 N. Webster Street VOLUME XLIII, No. 1 Review Red Cloud, Nebraska 68970 Summer, 1999 Telephone (402) 746-2653 "The Heart of Another Isa Dark Forest": A Reassessment of Professor St. Peter and His Wife Jean Tsien Beijing Foreign Studies University The Professor’s House is a a male subject (the professor) rich and complex work which gazing at female objects much can be rea~l rewardingly from of the time -- and not usually in many aspens: as a critique of admiration. Lillian St. Peter and soulless American materialism her daughters are seen through in the 1920s, as a depiction of ’ the critical -- at times, harsh -- male midlife crisis involving gaze of Godfrey St. Peter, who steady withdrawal into the self repeatedly offers comments on in preparation for death, as the them they cannot repudiate; for, story of the destruction of youth- as objects of a male gaze, they ful intellectual idealism and are not given a chance to reveal ’letting go with the heart,’ as their thoughts. While the two autobiographical parallels of male protagonists (Tom Outland Cather’s personal problems, and St. Peter) are depicted as and in many other ways. idealists, their women (Rosa- This paper attempts to read mond, according to Louie, ’~irtu- the work closely from a feminist ally [Tom’s] widow") are cold point of view. As we know, and hard and seen either quar- there is no "pure writing" exist- reling or spending money ing in a vacuum outside gender.