Rhodes & Singer Page Proof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions by Ned Hémard

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Bonanza in the Big Easy Born in Ottawa, Canada, to Russian Jewish immigrants, this actor appeared as Monsieur Mercier in the 1958 Paramount Pictures film, The Buccaneer (which embellishes the role of Jean Lafitte (Yul Brynner) in helping Andrew Jackson (Charlton Heston) win the Battle of New Orleans. After a long and successful run in a weekly television series, this actor also reigned as Bacchus during the 1985 New Orleans Mardi Gras season. If the reader has not guessed by now, the actor mentioned above is Lorne Greene (the patriarch Ben Cartwright, star of Bonanza). The fictional setting for the show (according to the premiere episode's storyline) is a 600,000-acre ranch on the shores of Lake Tahoe known as the Ponderosa. Nestled high in the Sierra Nevada, with a large ranch house in its center, the Ponderosa spread is bigger than Don Corleone’s compound (also on Lake Tahoe), where the elaborate First Communion party scenes were filmed for The Godfather Part II. Ben Cartwright is said to have built the original, smaller homestead after moving from New Orleans with his pregnant third wife Marie de Marigny (that’s right, just like the Faubourg) and his two sons, Adam and Hoss (played by Pernell Roberts and Dan Blocker). The grown Adam designed the later sprawling ranch house as depicted on TV. The Ponderosa was roughly a two-hour ride on horseback from Virginia City, Nevada. Most people believe that the inspiration for the name Ponderosa was the great number of Ponderosa pines in the area, but it could’ve been taken from the Latin for large and ponderous in size. -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

Wayne Rogers - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Wayne Rogers - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wayne_Rogers#Fox_News.27_Cashin.27_In From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia William Wayne McMillan Rogers III[1] (born April 7, 1933) is an American film and television actor, best known Wayne Rogers for playing the role of "Trapper John" McIntyre in the CBS television series, M*A*S*H. He is a regular panel member on the Fox News Channel stock investment television program Cashin' In, as a result of having built a highly successful and lucrative second career as an investor, investment strategist and advisor, and money manager. 1 Life and career 1.1 M*A*S*H (1972–1975) 1.2 Departure from M*A*S*H Rogers as Trapper John in M*A*S*H, 1972 1.3 House Calls (1979–1982) and other roles Born William Wayne McMillan Rogers III April 7, 1933 1.4 Fox News' Cashin' In Birmingham, Alabama, U.S. 1.5 Later developments Alma mater Princeton University 1.6 Awards Occupation Actor, director, screenwriter, 1.7 Personal life investor, television personality 2 References Years active 1959–present 3 External links Spouse(s) Mitzi McWhorter (1960–1983) Amy Hirsh (1988–present) Rogers was born in Birmingham, Alabama. He attended Ramsay High School in Birmingham and is a graduate of The Webb School in Bell Buckle, Tennessee. In 1954, he graduated from Princeton University with a history degree and was a member of the Princeton Triangle Club and the Eating Club Tiger Inn. Rogers served in the United States Navy before he became an actor. -

Televising the South: Race, Gender, and Region in Primetime, 1955-1980

TELEVISING THE SOUTH: RACE, GENDER, AND REGION IN PRIMETIME, 1955-1980 by PHOEBE M. BRONSTEIN A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2013 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Phoebe M. Bronstein Title: Televising the South: Race, Gender, and Region in Primetime, 1955-1980 This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: Carol Stabile Chairperson Priscilla Ovalle Core Member Courtney Thorsson Core Member Meslissa Stuckey Institutional Representative and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2013 ii © 2013 Phoebe M. Bronstein This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Phoebe Bronstein Doctor of Philosophy Department of English September 2013 Title: Televising the South: Race, Gender, and Region in Primetime, 1955-1980 This dissertation traces the emergence of the U.S. South and the region’s role in primetime television, from the post-World War II era through Reagan’s election in 1980. These early years defined, as Herman Gray suggests in Watching Race, all subsequent representations of blackness on television. This defining moment, I argue, is one inextricably tethered to the South and the region’s anxiety ridden and complicated relationship with television. This anxiety was rooted in the progress and increasing visibility of the Civil Rights Movement, concern over growing white southern audiences in the wake of the FCC freeze (ended in 1952), and the fear and threat of a southern backlash against racially progressive programming. -

Filabres-Alhamilla

Guide Tourist-Cinematographic Route Filabres-Alhamilla SCENE TAKE Una Comarca de cine... Guide Tourist-Cinematographic Route Filabres-Alhamilla In memory of the movie world in Almeria as a prime cultural legacy and a present and future tourist asset. To all the tourists and visitors who want to enjoy a region full of light, colours and originality. Promoted and edited by Commonwealth of Municipalities for the Development of Interior Towns Idea and general coordination José Castaño Aliaga, manager of the Tourist Plan of Filabres-Alhamilla Malcamino’s Route design, texts, documentation, tourist information, stills selection, locations, docu- mentary consultancy, Road Book creation, maps and GPS coordinates. Malcamino’s Creative direction www.oncepto.com Design and layout Sonja Gutiérrez Front-page picture Sonja Gutiérrez Printing Artes Gráficas M·3 Legal deposit XXXXXXX Translation Itraductores Acknowledgement To all the municipalities integrated in the Commonwealth of Municipalities for the De- velopment of Interior Towns: Alcudia de Monteagud, Benitagla, Benizalón, Castro de Fi- labres, Lucainena de las Torres, Senés, Tabernas, Tahal, Uleila del Campo and Velefique Documentation and publications for support and/or interest Almería, Plató de Cine – Rodajes Cinematográficos (1951-2008) – José Márquez Ubeda (Diputación Provincial de Almería) Almería, Un Mundo de Película – José Enrique Martínez Moya (Diputación Provincial de Almería) Il Vicino West – Carlo Gaberscek (Ribis) Western a la Europea, un plato que se sirve frio – Anselmo Nuñez Marqués (Entrelíneas Editores) La Enciclopedia de La Voz de Almería Fuentes propias de Malcamino’s Reference and/or interest Webs www.mancomunidadpueblosdelinterior.es www.juntadeandalucia.es/turismocomercioydeporte www.almeriaencorto.es www.dipalme.org www.paisajesdecine.com www.almeriaclips.com www.tabernasdecine.es www.almeriacine.es Photo: Sonja Gutiérrez index 9 Prologue “Land of movies for ever and ever.. -

Nosferatu. Revista De Cine (Donostia Kultura)

Nosferatu. Revista de cine (Donostia Kultura) Título: Filmografía Autor/es: Devesa, Dolores; Potes, Alicia Citar como: Devesa, D.; Potes, A. (1993). Filmografía. Nosferatu. Revista de cine. (12):72- 77. Documento descargado de: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/40864 Copyright: Reserva de todos los derechos (NO CC) La digitalización de este artículo se enmarca dentro del proyecto "Estudio y análisis para el desarrollo de una red de conocimiento sobre estudios fílmicos a través de plataformas web 2.0", financiado por el Plan Nacional de I+D+i del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España (código HAR2010-18648), con el apoyo de Biblioteca y Documentación Científica y del Área de Sistemas de Información y Comunicaciones (ASIC) del Vicerrectorado de las Tecnologías de la Información y de las Comunicaciones de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Entidades colaboradoras: El diablo de las aguas turbws (Hell and High Water, 1954) Filmografía r::x: Dolores Devesa y Alicia Potes pert Productions (EEUU). Argumento: (Sargento Zack), Robe1t Hutton (Solda Como director basado en un artículo publicado en Ame do "Conchie" Bronte), Richard Loo rican Weekly. Guión: Samuel Fuller. (Sargento Tanaka) , Steve Brodie (Te Supervisión del guión: Dorothy B. niente Drisco /1) , James Edwru·ds (Cabo Balas vengadoras(/ Shot Jesse James, Cormack. Fotografía: James Wong Thompson), Sid Melton (loe), Richru·d 1949) Howe. Música: Paul Dunlap. Montaje: Monahan (So ldado Bale/y), William Atthm Hilton. Intérpretes: Vincent Pri Chun ("Short Round", muchacho corea Producción:Lippert Product. (EEUU). ce (James Addison Reavis) , Ellen Drew no). Duración: 84 min. B/N. Estreno: Argumento: basado en un artículo de (Sofía Peralta Reavis), Beulah Bondi Madrid: Paz: 22 de junio de 1959. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

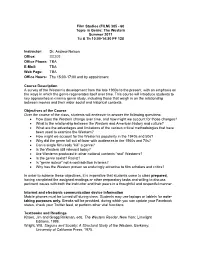

Course Number and Section

Film Studies (FILM) 305 - 60 Topic in Genre: The Western Summer 2011 Tu & Th 10:00-14:50 PF 128 Instructor: Dr. Andrew Nelson Office: SS209 Office Phone: TBA E-Mail: TBA Web Page: TBA Office Hours: Thu 15:00-17:00 and by appointment Course Description A survey of the Western‟s development from the late 1930s to the present, with an emphasis on the ways in which the genre regenerates itself over time. This course will introduce students to key approaches in cinema genre study, including those that weigh in on the relationship between movies and their wider social and historical contexts. Objectives of the Course Over the course of the class, students will endeavor to answer the following questions: How does the Western change over time, and how might we account for those changes? What is the relationship between the Western and American history and culture? What are the advantages and limitations of the various critical methodologies that have been used to examine the Western? How might we account for the Western‟s popularity in the 1940s and 50s? Why did the genre fall out of favor with audiences in the 1960s and 70s? Can a single film really “kill” a genre? Is the Western still relevant today? Are Westerns produced in other national contexts “real” Westerns? Is the genre sexist? Racist? Is “genre auteur” not a contradiction in terms? Why has the Western proven so enduringly attractive to film scholars and critics? In order to achieve these objectives, it is imperative that students come to class prepared, having completed the assigned readings or other preparatory tasks and willing to discuss pertinent issues with both the instructor and their peers in a thoughtful and respectful manner. -

Budd Boetticher:Programme Notes.Qxd

Decision at Sundown USA | 1957 | 78 minutes Credits In Brief Director Budd Boetticher Bart Allison arrives in Sundown planning to kill Tate Kimbrough. Three years earlier he Screenplay Charles Lang (story by believed Kimbrough was responsible for the death of his wife. He finds Kimbrough and Vernon L. Fluharty) warns him he is going to kill him but gets pinned down in the livery stable with his friend Sam by Kimbrough’s stooge Sheriff and his men. When Sam is shot in the back Photography Burnett Guffey after being told he could leave safely, some of the townsmen change sides and disarm Music Heinz Roemheld the Sheriff’s men forcing him to face Allison alone. Taking care of the Sheriff, Allison injures his gun hand and must now face Kimbrough left-handed. Cast Bart Allison Randolph Scott Tate Kimbrough John Carroll Lucy Summerton Karen Steele Ruby James Valerie French Decision At Sundown is a highly unusual Randolph Scott/Budd Boetticher Western in which Scott's ordinarily driven but heroic persona is tainted, twisted, by an irrational, all-consuming hatred. Boetticher keeps the tension high in this mostly static, action-free chamber Western, in which the emotional and philosophical undercurrents of the story are developed slowly and patiently. Scott plays Bart Allison, a man overwhelmed by a desire for revenge. He arrives in the town of Sundown, along with his pal Sam (Noah Beery), after three years of searching for a man named Tate Kimbrough (John Carroll). It's not clear at first why exactly Bart wants revenge, though it's hinted, with increasing pointedness, that it might have something to do with Bart's wife, Mary — which makes it ironic that when Bart and Sam arrive in town, Kimbrough is getting married later that day to local girl Lucy (Karen Steele). -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Cineteca Del Comune Di Bologna

XXXVII Mostra Internazionale del Cinema Libero IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Cineteca del Comune di Bologna XXII edizione / 22nd Edition Sabato 28 giugno - Sabato 5 luglio / Saturday 28 June - Saturday 5 July Questa edizione del festival è dedicata a Vittorio Martinelli This festival’s edition is dedicated to Vittorio Martinelli IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Via Azzo Gardino, 65 - tel. 051 219 48 14 - fax 051 219 48 21 - cine- XXII edizione [email protected] Segreteria aperta dalle 9 alle 18 dal 28 giugno al 5 luglio / Secretariat Con il contributo di / With the financial support of: open June 28th - July 5th -from 9 am to 6 pm Comune di Bologna - Settore Cultura e Rapporti con l'Università •Cinema Lumière - Via Azzo Gardino, 65 - tel. 051 219 53 11 Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna •Cinema Arlecchino - Via Lame, 57 - tel. 051 52 21 75 Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali - Direzione Generale per il Cinema Modalità di traduzione / Translation services: Regione Emilia-Romagna - Assessorato alla Cultura Tutti i film delle serate in Piazza Maggiore e le proiezioni presso il Programma MEDIA+ dell’Unione Europea Cinema Arlecchino hanno sottotitoli elettronici in italiano e inglese Tutte le proiezioni e gli incontri presso il Cinema Lumière sono tradot- Con la collaborazione di / In association with: ti in simultanea in italiano e inglese Fondazione Teatro Comunale di Bologna All evening screenings in Piazza Maggiore, as well as screenings at the L’Immagine Ritrovata Cinema Arlecchino, will be translated into Italian