Record of Witness Testimony 282

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust Glossary

Holocaust Glossary A ● Allies: 26 nations led by Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union that opposed Germany, Italy, and Japan (known as the Axis powers) in World War II. ● Antisemitism: Hostility toward or hatred of Jews as a religious or ethnic group, often accompanied by social, economic, or political discrimination. (USHMM) ● Appellplatz: German word for the roll call square where prisoners were forced to assemble. (USHMM) ● Arbeit Macht Frei: “Work makes you free” is emblazoned on the gates at Auschwitz and was intended to deceive prisoners about the camp’s function (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Aryan: Term used in Nazi Germany to refer to non-Jewish and non-Gypsy Caucasians. Northern Europeans with especially “Nordic” features such as blonde hair and blue eyes were considered by so-called race scientists to be the most superior of Aryans, members of a “master race.” (USHMM) ● Auschwitz: The largest Nazi concentration camp/death camp complex, located 37 miles west of Krakow, Poland. The Auschwitz main camp (Auschwitz I) was established in 1940. In 1942, a killing center was established at Auschwitz-Birkenau (Auschwitz II). In 1941, Auschwitz-Monowitz (Auschwitz III) was established as a forced-labor camp. More than 100 subcamps and labor detachments were administratively connected to Auschwitz III. (USHMM) Pictured right: Auschwitz I. B ● Babi Yar: A ravine near Kiev where almost 34,000 Jews were killed by German soldiers in two days in September 1941 (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Barrack: The building in which camp prisoners lived. The material, size, and conditions of the structures varied from camp to camp. -

Zum Selbstverständnis Von Frauen Im Konzentrationslager. Das Lager Ravensbrück

Zum Selbstverständnis von Frauen im Konzentrationslager. Das Lager Ravensbrück. von der Fakultät I Geisteswissenschaften der Technischen Universität Berlin genehmigte Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie vorgelegt von Silke Schäfer aus Berlin D 83 Berichter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Benz Berichterin: Prof. Dr. Johanna Bleker (FUB) Tag der Wissenschaftlichen Aussprache 06. Februar 2002 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 4 1 Problemfelder und Nachkriegsprozesse 11 1.1 Begriffsklärung 11 1.1.1 Sprache 13 1.1.2 Das nationalsozialistische "Frauenbild" 14 1.1.3 Täterinnen 18 1.1.4 Kategorien für Frauen im Konzentrationslager 19 1.1.5 Auswahlkriterien 26 1.2 Strafverfolgung 28 1.2.1 Militärgerichtsverfahren 29 1.2.2 Die Hamburger Ravensbrück-Prozesse 32 1.2.3 Strafverfahren vor deutschen Gerichten 38 1.2.4 Strafverfahren vor anderen Gerichten 40 2 Topographie 42 2.1 Vorgeschichte 42 2.1.1 Moringen 42 2.1.2 Lichtenburg 45 2.2 Das Frauen-KZ Ravensbrück 47 2.2.1 "Alltagsleben" 52 2.2.2 Solidarität 59 2.3 Arbeit 62 2.3.1 Arbeitskommandos 63 2.3.2 Wirtschaftliche Ausbeutung 64 2.3.3 Lagerbordelle und SS-Bordelle 69 2.4 Aufseherinnen 75 2.4.1 Strafen 77 2.5 Lager bei Ravensbrück 80 2.5.1 Männerlager 81 2.5.2 Jugendschutzlager Uckermark 81 3 Die Medizin 86 3.1 Der Blick auf die Mediziner 86 3.1.1 Das Revier 87 3.2 Medizinische Experimente 89 3.2.1 Sulfonamidversuche / Knochen-, 91 Muskel- und Nervenoperation Sulfonamidversuche 93 Knochen-, Muskel- und Nervenoperation 104 Versuche 108 3.3 Sterilisation 110 3.3.1 Geburten und Kinder 115 3.4 Das medizinische Personal 123 3.4.1 NS-Ärztinnen - Lebensskizzen 125 Jantzen geb. -

8 9 14 18 26 27 28 28 30 32 33 34 37 40 45 46 76 77 86 100 122 132 133 134 134 135 135 135 136 146 Dr. Werner Jung, NS-Dokumenta

8 VORWORTE Baracke 1 (Strafkompanie), Lagerabschnitt Blb / Frauenorchester, 9 Dr. Werner Jung, NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln Lagerabschnitte Bla und Blb / Baracke 30 (Experimentierbaracke), 14 Andrzej Kacorzyk, Staatliches Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau Lagerabschnitt Bla / Frauenlager, Lagerabschnitte Bla und Blb / i6 Prof. Dr. Gideon Greif, Tel Aviv Todesblock 25, Lagerabschnitt Bla / Quarantänebaracken für 18 Peter Siebers, Köln weibliche Entlassungshäftlinge, außerhalb des Lagerabschnitts Bla / Eingangsgebäude von Birkenau 20 TODESFABRIK AUSCHWITZ 20 Topografie und Alltag in einem Konzentrations- und Vernichtungslager 166 BESONDERE LAGERBEREICHE 22 Deportationen nach Auschwitz 166 „Alte Rampe“ und „Rampe“ 176 „Alte Sauna“ und „Neue Sauna“ 26 KL AUSCHWITZ I - STAMMLAGER 192 „Zigeunerlager“ , Lagerabschnitt Blle 27 Von der Lagergründung bis zur Evakuierung 202 Frauenlager, Lagerabschnitte Bla, Blb, Blle, Bllb 28 Lagergründung 212 Männerlager, Lagerabschnitte Blb, Bild, Bllf 28 Vom Konzentrations- zum Vernichtungslager 30 „Interessengebiet“ des Konzentrationslagers Auschwitz 228 PLANUNG UND UMSETZUNG DER „ENDLÖSUNG“ 32 Lagerstruktur 236 Die ersten Gaskammern 33 Nebenlager 238 Krematorien II und III 34 Lagerleitung 270 Krematorien IV und V 37 Die Architekten von Auschwitz 40 Bestand 1940 und Lagererweiterung 1944 284 KL AUSCHWITZ III - MONOWITZ 45 Evakuierung 290 IG Farbenindustrie AG 291 Planungen für die Buna-Werke 46 ORTE UND GEBÄUDE IM STAMMLAGER 292 Häftlinge als Arbeiter Aufnahmegebäude und Wäscherei / Fahrbereitschaft und -

An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps

Chaos, Coercion, and Organized Resistance; An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas Vernon Maher Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. J. Craig Jenkins, Co-Advisor Dr. Vincent Roscigno, Co-Advisor Dr. Andrew W. Martin Copyright by Thomas V. Maher 2013 Abstract Research on organizations and bureaucracy has focused extensively on issues of efficiency and economic production, but has had surprisingly little to say about power and chaos (see Perrow 1985; Clegg, Courpasson, and Phillips 2006), particularly in regard to decoupling, bureaucracy, or organized resistance. This dissertation adds to our understanding of power and resistance in coercive organizations by conducting an analysis of the Nazi concentration camp system and nineteen concentration camps within it. The concentration camps were highly repressive organizations, but, the fact that they behaved in familiar bureaucratic ways (Bauman 1989; Hilberg 2001) raises several questions; what were the bureaucratic rules and regulations of the camps, and why did they descend into chaos? How did power and coercion vary across camps? Finally, how did varying organizational, cultural and demographic factors link together to enable or deter resistance in the camps? In order address these questions, I draw on data collected from several sources including the Nuremberg trials, published and unpublished prisoner diaries, memoirs, and testimonies, as well as secondary material on the structure of the camp system, individual camp histories, and the resistance organizations within them. My primary sources of data are 249 Holocaust testimonies collected from three archives and content coded based on eight broad categories [arrival, labor, structure, guards, rules, abuse, culture, and resistance]. -

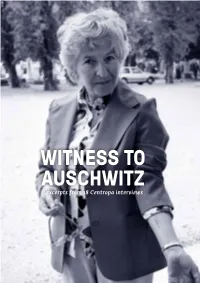

WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews

WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ excerpts from 18 Centropa interviews WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews As the most notorious death camp set up by the Nazis, the name Auschwitz is synonymous with fear, horror, and genocide. The camp was established in 1940 in the suburbs of Oswiecim, in German-occupied Poland, and later named Auschwitz by the Germans. Originally intended to be a concentration camp for Poles, by 1942 Auschwitz had a second function as the largest Nazi death camp and the main center for the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. Auschwitz was made up of over 40 camps and sub-camps, with three main sec- tions. The first main camp, Auschwitz I, was built around pre-war military bar- racks, and held between 15,000 and 20,000 prisoners at any time. Birkenau – also referred to as Auschwitz II – was the largest camp, holding over 90,000 prisoners and containing most of the infrastructure required for the mass murder of the Jewish prisoners. 90 percent of Auschwitz’s victims died at Birkenau, including the majority of the camp’s 75,000 Polish victims. Of those that were killed in Birkenau, nine out of ten of them were Jews. The SS also set up sub-camps designed to exploit the prisoners of Auschwitz for slave labor. The largest of these was Buna-Monowitz, which was established in 1942 on the premises of a synthetic rubber factory. It was later designated the headquarters and administrative center for all of Auschwitz’s sub-camps, and re-named Auschwitz III. All the camps were isolated from the outside world and surrounded by elec- trified barbed wire. -

Buchenwald Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 51°01′20″N 11°14′53″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Buchenwald concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 51°01′20″N 11°14′53″E "Buchenwald" redirects here. For other uses, see Buchenwald (disambiguation). Navigation Buchenwald concentration camp (German: Konzentrationslager (KZ) Buchenwald, IPA: Main page [ˈbuːxәnvalt]; literally, in English: beech forest) was a German Nazi concentration camp Contents established on the Ettersberg (Etter Mountain) near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937, one of Featured content the first and the largest of the concentration camps on German soil, following Dachau's Current events opening just over four years earlier. Random article Donate to Wikipedia Prisoners from all over Europe and the Soviet Union—Jews, non-Jewish Poles and Slovenes, the mentally ill and physically-disabled from birth defects, religious and political prisoners, Roma and Sinti, Freemasons, Jehovah's Witnesses, criminals, homosexuals, and prisoners of Interaction war — worked primarily as forced labor in local armaments factories.[1] From 1945 to 1950, Help the camp was used by the Soviet occupation authorities as an internment camp, known as About Wikipedia NKVD special camp number 2. Community portal Today the remains of Buchenwald serves as a memorial and permanent exhibition and Recent changes museum.[2] Contact Wikipedia Contents Toolbox 1 History 2 People What links here 2.1 Camp commandants Related changes 2.2 Female prisoners and overseers Upload file 2.3 Allied airmen Special pages 3 Death toll -

PDF Download

1 1. Frankfurter Auschwitz-Prozess »Strafsache gegen Mulka u.a.«, 4 Ks 2/63 Landgericht Frankfurt am Main 170. Verhandlungstag, 21.6.1965 und 171. Verhandlungstag, 25.06.1965 Plädoyer des Verteidigers Staiger für Hofmann Vorsitzender Richter: Ich darf nun Herrn Rechtsanwalt Doktor Staiger um seine Ausführungen bitten. Verteidiger Staiger: Herr Präsident, meine Damen und Herren Richter und Geschworenen, als mein Mandant Hofmann am 1.12.1942 zum KL Auschwitz kam, war dort, wie Herr Staatsanwalt Vogel zutreffend hervorhob, die Todesmaschinerie bereits voll im Gange. Die vom Führer und Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler schon 1941 befohlene und in der Wannsee-Konferenz von den Repräsentanten des Reichs und der Justiz widerspruchslos akzeptierte »Endlösung der Judenfrage« durch physische Vernichtung war eine von uns heute als unfaßbar angesehene Realität geworden. Hofmann erhielt die Stellung eines 3. Schutzhaftlagerführers zugewiesen, eine Funktion, die es bis dahin nicht gegeben hatte und die auch nach seiner Versetzung am 15. Mai 1944 nicht mehr existierte. Er war also zunächst innerhalb der SS-Hierarchie im Lager nicht Befehlsgeber, sondern Befehlsempfänger. Er ordnete nicht an, sondern führte Anordnungen des 1. Schutzhaftlagerführers Aumeier und des 2. Schutzhaftlagerführers Schwarz, nach der Versetzung Aumeiers des 1. Schutzhaftlagerführers Schwarz und des 2. Schutzhaftlagerführers Max Sell, denen er bis zum Beginn der Kommandantur durch den neuen Kommandanten Liebehenschel unterstellt war, aus. Die Stellung des 3. Schutzhaftlagerführers war praktisch überflüssig. Man hatte Hofmann von Dachau nach Auschwitz einfach abgeschoben, und zwar offensichtlich deshalb, weil er, wie ich später noch unter Beweis stellen werde, dem dortigen Kommandanten und dem Inspekteur der KL, SS- Obergruppenführer Glücks, durch seine Gesuche um Frontversetzung unliebsam geworden war. -

1942 Other Victims of Nazi Crimes Scenario

OTHER VICTIMS subject OF NAZI CRIMES Context8. According to the Nazi ideology, Jews into two categories: ‘worthy’ individuals constituted the greatest threat to Ger- (enjoying full civic rights) and those man society and racial purity. For this rea- ‘useless’ not only denied equal rights, but son, their rights were gradually limited with primarily the right to live. isolation in designated areas after the war broke out. Then, they were murdered in death Several months after the Nazis gained power, camps and other murder sites. a law was enacted on 14 July 1933 ‘to prevent the birth of offspring with hereditary diseases’. However, Jews were not the only group persecuted Over time, that regulation was used to forcibly by the Nazis. Even before the Second World War sterilise people with mental illnesses and those had begun, they sought to ‘purify’ German society suffering from epilepsy, deafness, blindness and from all ‘racially different’ groups (to which Sinti physical deformities. That group also included and Roma belonged, alongside Jews), as well as alcohol addicts, who were subject forced persons with physical disabilities, mental-health sterilisation. According to estimates, between difficulties and ones considered to be anti-social. 200,000 and 380,000 persons underwent the The last-mentioned group included homosexuals treatment pursuant to that law by 1938. However, and prostitutes and, given their nomadic lifestyle, no attempts were made to murder them before Sinti and Roma. Political opponents (mainly the Second World War. A certain type of exception socialists and communists as well as various and impulse toward adopting such a decision later union and social activists opposed to the Nazis) in the autumn of 1939 was a certain Kretschmar constituted a separate category. -

1 GISELA RABITSCH: DAS KL MAUTHAUSEN In

GISELA RABITSCH: DAS KL MAUTHAUSEN In: Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Jg. 21, Stuttgart 1970, S. 50-92 Die Gründung des Lagers 1938 Wenn das genaue Gründungsdatum des KL Mauthausen auch bis jetzt nicht ermittelt werden konnte, so liegen doch einige Hinweise vor, die zumindest eine annähernde Zeitbestimmung ermöglichen. Im Mai 1938 unternahmen der Inspekteur der KL, SS-Obergruppenführer Eicke, der damalige SS-Gruppenführer Pohl, der zu diesem Zeitpunkt den Posten des Chefs des „Verwaltungsamtes-SS“ innehatte, und ein technischer Stab eine Dienstreise, die der Besichtigung „günstiger Gelände“ für die Errichtung neuer Konzentrationslager dienen sollte1. Die Reise führte zuerst nach Flossenbürg und anschließend nach Mauthausen; in beiden Fällen wurde von Pohl und Eicke entschieden, die Gründung eines KL zu veranlassen, in beiden Fällen dürften die vorhandenen Steinbrüche und die damit verbundene Möglichkeit des Arbeitseinsatzes der künftigen Lagerinsassen ausschlaggebend gewesen sein. Kurz darauf wurde der bei Mauthausen gelegene Steinbruch „Wiener Graben“, bis dahin im Besitz der Stadt Wien, von der „DEST“2 erworben. Die Frage, welches Motiv schließlich für die Gründung eines KL in Mauthausen, einem kleine Ort an der Donau, bestimmend gewesen sei, lässt sich aus den Quellen nicht eindeutig beantworten; es mag dies die Lage Mauthausen in der Nähe von Linz oder aber die durch die Steinbrüche vorhandene Arbeitsmöglichkeit für die Häftlinge gewesen sein. Dabei ist jedoch ein Zusammenwirken beider Motive nicht ausgeschlossen. Als ein weiterer Hinweis auf die Beweggründe für die Errichtung eines KL in Mauthausen kann folgende Tatsache gelten: am 15. Juni 1938 fand in München zwischen Pohl und Vertretern der Finanzabteilung der „deutschen Arbeitsfront“ eine Verhandlung über die Finanzierung der KL statt. -

Matter of Kulle

Interim Decision #3002 MATTER OF KULLE In Deportation Proceedings A-10857195 . Decided by Board December 10, 1.985 (1) The term "persecution" as used in section 241(aX19) of the Immigration and Na- tionality Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1251(aX19) (1982), includes the confinement of political prisoners, Jehovah's Witnesses, Protestant and Catholic clergy, Jews, and other opponents of the Nazi regime in the Nazi work camp at Gross-Rosen. (2) Those persons who actively participated in the management of Nazi concentra- tion camps which included the supervising and training of concentration camp guards engaged in persecution as defined under section 241(a)(19) of the Act,. (3) The respondent, a concentration camp guard at Gross-Rosen, assisted in the per- secution of prisoners who, because of their religious and political beliefs, were sin- gled out for harsher treatment. (4) The respondent was found to have assisted in the persecution of prisoners under section 241(aX19) of the Act notwithstanding the absence of evidence that his ac- tivities were the result of political or religious motivation. (5) The respondent, who claimed that he merely obeyed orders and was denied a transfer from the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, did assist in persecution and is deportable under section 241(aX19) of the Act, notwithstanding his claim that his actions were involuntary. (6) The respondent materially misrepresented his wartime military service to immi- gration authorities and thus is deportable as excludable at entry under sections 212(a) (19) and (20) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. §§ 1182(a) (19) and (20) (1982). -

Liberated on Film: Images and Narratives of Camp Liberation in Historical Footage and Feature Films 25/11/19

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Ulrike Weckel Liberated on Film: Images and Narratives of Camp Liberation in Historical Footage and Feature Films 25/11/19 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Weckel, Ulrike: Liberated on Film: Images and Narratives of Camp Liberation in Historical Footage and Feature Films. In: Research in Film and History. Research, Debates and Projects 2.0 (25/11/19), Nr. 2, S. 1–21. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 1 Liberated on Film: Images and Narratives of Camp Liberation in Historical Footage and Feature Films Ulrike Weckel Published: November 25, 2019 Figure 1. AUSCHWITZ: FILM DOCUMENTS OF THE MONSTROUSLY EVIL CRIMES OF THE GERMAN GOVERNMENT IN AUSCHWITZ, Elizaveta Svilova, SU 1945 Since SS camp personnel obeyed the strict prohibition against photography in Nazi annihilation, concentration, and work camps, the footage that Allied cameramen shot in such camps during and shortly after their liberation filled this void in visual documentation. Thus, what we imagine went on in Nazi camps while in operation has been shaped by pictures that document their very last stages, after the SS had fled most of these crime scenes, most inmates had been killed or died, and tens of thousands of the still living had been evacuated on death marches. -

Transcript of Spoken Word

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection 1 Interview with Dr. Reidar Dittmann By Harlan Jacobs November 3, 1983 Jewish Community Relations Council, Anti-Defamation League of Minnesota and the Dakotas HOLOCAUST ORAL HISTORY TAPING PROJECT Q: Professor, can you tell us briefly what you are doing these days, and perhaps even how you came to America? A: Yes. A am a professor at St. Olaf College here in Northfield. My field of teaching is art history. And we are, in fact, doing this interview in part of my responsibility. That’s the Art Gallery at St. Olaf. Q: It’s a very beautiful gallery, I might add. A: Yes, it’s a nice old building for being in America! It’s a building that will rather soon be on the National Registry, because if anything is a hundred years old in the Midwest, it’s “ancient!” I came to America ages and ages ago in 1945 which was immediately after World War II and came directly to Northfield with some necessary stopovers in New York and in Chicago. I came to this part of the world as a result of what had happened during the war. Q: Now you were a concentration camp prisoner? A: Yes, I was. And certain things, of course, led up to that. But this place where I am now teaching, St. Olaf College, is an institution that was established by Norwegian immigrants somewhat more than a hundred years ago. The founders of this institution and their successors had always felt very close to Norway, and during World War II, when Norway was occupied by the Germans, the people around here were as upset about that as anything in the world, that the Germans had infringed upon the holy territory of Norway.