Transcript of Spoken Word

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust Glossary

Holocaust Glossary A ● Allies: 26 nations led by Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union that opposed Germany, Italy, and Japan (known as the Axis powers) in World War II. ● Antisemitism: Hostility toward or hatred of Jews as a religious or ethnic group, often accompanied by social, economic, or political discrimination. (USHMM) ● Appellplatz: German word for the roll call square where prisoners were forced to assemble. (USHMM) ● Arbeit Macht Frei: “Work makes you free” is emblazoned on the gates at Auschwitz and was intended to deceive prisoners about the camp’s function (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Aryan: Term used in Nazi Germany to refer to non-Jewish and non-Gypsy Caucasians. Northern Europeans with especially “Nordic” features such as blonde hair and blue eyes were considered by so-called race scientists to be the most superior of Aryans, members of a “master race.” (USHMM) ● Auschwitz: The largest Nazi concentration camp/death camp complex, located 37 miles west of Krakow, Poland. The Auschwitz main camp (Auschwitz I) was established in 1940. In 1942, a killing center was established at Auschwitz-Birkenau (Auschwitz II). In 1941, Auschwitz-Monowitz (Auschwitz III) was established as a forced-labor camp. More than 100 subcamps and labor detachments were administratively connected to Auschwitz III. (USHMM) Pictured right: Auschwitz I. B ● Babi Yar: A ravine near Kiev where almost 34,000 Jews were killed by German soldiers in two days in September 1941 (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Barrack: The building in which camp prisoners lived. The material, size, and conditions of the structures varied from camp to camp. -

The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – a Guide to The

PUBLISHED BY Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial Jean-Dolidier-Weg 75 21039 Hamburg Phone: +49 40 428131-500 [email protected] www.kz-gedenkstaette-neuengamme.de EDITED BY Karin Schawe TRANSLATED BY Georg Felix Harsch PHOTOS unless otherwise indicated courtesy We would like to thank the Friends of of the Neuengamme Memorial‘s Archive the Neuengamme Memorial association and Michael Kottmeier for their financial support. Maps on pages 29 and 41: © by M. Teßmer, graphische werkstätten This brochure was produced with feldstraße financial support from the Federal Commissioner for Culture and the Media GRAPHIC DESIGN BY based on a decision by the Bundestag, Annrika Kiefer, Hamburg the German parliament. The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – PRINTED BY A Guide to the Site‘s History and the Memorial Druckerei Siepmann GmbH, Hamburg Hamburg, November 2010 The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – A Guide to the Site‘s History and the Memorial The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – A Guide to the Site's History and the Memorial Published by the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial Edited by Karin Schawe Contents 6 Preface 10 The NeueNgamme coNceNTraTioN camP, 1938 To 1945 12 chronicle of events, 1938 to 1945 20 The construction of the Neuengamme concentration camp 22 The Prisoners 22 German Prisoners 25 Prisoners from the Occupied Countries 30 The concentration camp SS 31 Slave Labour 35 housing 38 Death 40 The Satellite camps 42 The end 45 The Victims of the Neuengamme concentration camp 46 The SiTe afTer 1945 48 chronicle of events from 1945 58 The British internment camp 59 The Transit camp 60 The Prisons and the memorial at the historical Site of the concentration camp Contents 66 The NeueNgamme coNceNTraTioN camP memoriaL 70 The grounds 93 archives and Library 70 The house of commemoration 93 The Archive 72 The exhibitions 95 The Library 72 Main Exhibition Traces of History 96 The Open Archive 73 Research Exhibition Posted to Neuengamme. -

Dear Educator, Jehovah's Witnesses, a Christian Community of 35,000 In

Dear Educator, Jehovah’s Witnesses, a Christian community of 35,000 in Germany and occupied lands, refused to conform to the Nazi ideology of hate. They suffered severely for their belief in nonviolence and their utter rejection of racism. Students are fascinated to learn that the Nazis offered the Witnesses the chance for freedom if they would sign a document renouncing their faith. Very few signed. Thrown into Nazi camps, they became eyewitnesses of Nazi genocide. As historian John Toland wrote, this is “a story of human courage that must be heard.” The Arnold-Liebster Foundation’s website at www.alst.org is an extensive educational resource that includes: • How to arrange for an interactive Skype conference between Simone Arnold Liebster and your students. • Jehovah’s Witnesses Stand Firm Against Nazi Assault documentary DVD and study guide. Please contact me for a free copy of the DVD. • Realizing the importance of Holocaust education, the Arnold-Liebster Foundation is willing to subsidize a major part of the cost of their traveling exhibits. • Online lesson plans, study guides, primary documents, online exhibitions, survivor testimony, classroom questions, educator comments, and more. In North Carolina and South Carolina, contact Diana Zientek for more information at [email protected], 828-645-7138. Please feel free to contact me if you have any questions. Sincerely, Sandra S. Milakovich [email protected] Twitter: @arnoldliebster U.S. Representative: 4004 Rodeo Road · Davenport, IA 52806 · 563.391.1819 · alst.org DACHAU PRINCIPAL DISTINGUISHING BADGES WORN BY PRISONERS 3 2 6 7 8 Political Criminal Antisocial Homosexual Emigrant Jehovah’s Witness Jewish Jewish Jewish Jewish Jewish Political Criminal Antisocial Homosexual Emigrant F Political Political Penal Wehrmacht Prisoners (French) Second-time Company Prisoners Under Special Offenders Surveillance Berben, Paul. -

Zum Selbstverständnis Von Frauen Im Konzentrationslager. Das Lager Ravensbrück

Zum Selbstverständnis von Frauen im Konzentrationslager. Das Lager Ravensbrück. von der Fakultät I Geisteswissenschaften der Technischen Universität Berlin genehmigte Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie vorgelegt von Silke Schäfer aus Berlin D 83 Berichter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Benz Berichterin: Prof. Dr. Johanna Bleker (FUB) Tag der Wissenschaftlichen Aussprache 06. Februar 2002 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 4 1 Problemfelder und Nachkriegsprozesse 11 1.1 Begriffsklärung 11 1.1.1 Sprache 13 1.1.2 Das nationalsozialistische "Frauenbild" 14 1.1.3 Täterinnen 18 1.1.4 Kategorien für Frauen im Konzentrationslager 19 1.1.5 Auswahlkriterien 26 1.2 Strafverfolgung 28 1.2.1 Militärgerichtsverfahren 29 1.2.2 Die Hamburger Ravensbrück-Prozesse 32 1.2.3 Strafverfahren vor deutschen Gerichten 38 1.2.4 Strafverfahren vor anderen Gerichten 40 2 Topographie 42 2.1 Vorgeschichte 42 2.1.1 Moringen 42 2.1.2 Lichtenburg 45 2.2 Das Frauen-KZ Ravensbrück 47 2.2.1 "Alltagsleben" 52 2.2.2 Solidarität 59 2.3 Arbeit 62 2.3.1 Arbeitskommandos 63 2.3.2 Wirtschaftliche Ausbeutung 64 2.3.3 Lagerbordelle und SS-Bordelle 69 2.4 Aufseherinnen 75 2.4.1 Strafen 77 2.5 Lager bei Ravensbrück 80 2.5.1 Männerlager 81 2.5.2 Jugendschutzlager Uckermark 81 3 Die Medizin 86 3.1 Der Blick auf die Mediziner 86 3.1.1 Das Revier 87 3.2 Medizinische Experimente 89 3.2.1 Sulfonamidversuche / Knochen-, 91 Muskel- und Nervenoperation Sulfonamidversuche 93 Knochen-, Muskel- und Nervenoperation 104 Versuche 108 3.3 Sterilisation 110 3.3.1 Geburten und Kinder 115 3.4 Das medizinische Personal 123 3.4.1 NS-Ärztinnen - Lebensskizzen 125 Jantzen geb. -

Jehovah's Witnesses in National Socialist Concentration Camps, 1933

Religion, State & Society, Vol. 34, No. 2, June 2006 Jehovah’s Witnesses in National Socialist Concentration Camps, 1933 – 45* JOHANNES S. WROBEL Introduction With thousands incarcerated in the prisons and concentration camps of the ‘Third Reich’, Jehovah’s Witnesses, or Ernste Bibelforscher (Earnest Bible Students), were among the main and earliest victim groups of the terror apparatus of the National Socialists between 1933 and 1945. The Watchtower History Archive of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Selters/Taunus, Germany (WTA, Zentralkartei), has thus far registered a total of over 4200 names of male (2900) and female (1300) believers of different nationalities who went through a National Socialist concentration camp by the end of the regime in 1945.1 Between 1933 and 1935/36 members of this Christian faith were sent to official early camps, and then in far greater numbers to the newly established ‘modern’ main concentration camps (Stammlager), such as Sachsenhausen (1936), Buchenwald (1937) and Ravensbru¨ ck (1939). A total of 2800 males and females went through these three camps alone by 1945. Allegedly enemies of the state, the Witnesses proved, as historian Christine King (1982, p. 169) has observed, to be ‘a small but memorable band of prisoners, marked by the violet triangle and noted for their courage and their convictions’. When the concentration camp system was reorganised in 1936, the SS administra- tion, controlled by Heinrich Himmler,2 introduced an elaborate classification of prisoners by means of badges with triangles and with black, green, pink, purple and red colours. Jehovah’s Witnesses in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp were assigned the purple triangle in July 1936 (Eberle, 2005, p. -

8 9 14 18 26 27 28 28 30 32 33 34 37 40 45 46 76 77 86 100 122 132 133 134 134 135 135 135 136 146 Dr. Werner Jung, NS-Dokumenta

8 VORWORTE Baracke 1 (Strafkompanie), Lagerabschnitt Blb / Frauenorchester, 9 Dr. Werner Jung, NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln Lagerabschnitte Bla und Blb / Baracke 30 (Experimentierbaracke), 14 Andrzej Kacorzyk, Staatliches Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau Lagerabschnitt Bla / Frauenlager, Lagerabschnitte Bla und Blb / i6 Prof. Dr. Gideon Greif, Tel Aviv Todesblock 25, Lagerabschnitt Bla / Quarantänebaracken für 18 Peter Siebers, Köln weibliche Entlassungshäftlinge, außerhalb des Lagerabschnitts Bla / Eingangsgebäude von Birkenau 20 TODESFABRIK AUSCHWITZ 20 Topografie und Alltag in einem Konzentrations- und Vernichtungslager 166 BESONDERE LAGERBEREICHE 22 Deportationen nach Auschwitz 166 „Alte Rampe“ und „Rampe“ 176 „Alte Sauna“ und „Neue Sauna“ 26 KL AUSCHWITZ I - STAMMLAGER 192 „Zigeunerlager“ , Lagerabschnitt Blle 27 Von der Lagergründung bis zur Evakuierung 202 Frauenlager, Lagerabschnitte Bla, Blb, Blle, Bllb 28 Lagergründung 212 Männerlager, Lagerabschnitte Blb, Bild, Bllf 28 Vom Konzentrations- zum Vernichtungslager 30 „Interessengebiet“ des Konzentrationslagers Auschwitz 228 PLANUNG UND UMSETZUNG DER „ENDLÖSUNG“ 32 Lagerstruktur 236 Die ersten Gaskammern 33 Nebenlager 238 Krematorien II und III 34 Lagerleitung 270 Krematorien IV und V 37 Die Architekten von Auschwitz 40 Bestand 1940 und Lagererweiterung 1944 284 KL AUSCHWITZ III - MONOWITZ 45 Evakuierung 290 IG Farbenindustrie AG 291 Planungen für die Buna-Werke 46 ORTE UND GEBÄUDE IM STAMMLAGER 292 Häftlinge als Arbeiter Aufnahmegebäude und Wäscherei / Fahrbereitschaft und -

An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps

Chaos, Coercion, and Organized Resistance; An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas Vernon Maher Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. J. Craig Jenkins, Co-Advisor Dr. Vincent Roscigno, Co-Advisor Dr. Andrew W. Martin Copyright by Thomas V. Maher 2013 Abstract Research on organizations and bureaucracy has focused extensively on issues of efficiency and economic production, but has had surprisingly little to say about power and chaos (see Perrow 1985; Clegg, Courpasson, and Phillips 2006), particularly in regard to decoupling, bureaucracy, or organized resistance. This dissertation adds to our understanding of power and resistance in coercive organizations by conducting an analysis of the Nazi concentration camp system and nineteen concentration camps within it. The concentration camps were highly repressive organizations, but, the fact that they behaved in familiar bureaucratic ways (Bauman 1989; Hilberg 2001) raises several questions; what were the bureaucratic rules and regulations of the camps, and why did they descend into chaos? How did power and coercion vary across camps? Finally, how did varying organizational, cultural and demographic factors link together to enable or deter resistance in the camps? In order address these questions, I draw on data collected from several sources including the Nuremberg trials, published and unpublished prisoner diaries, memoirs, and testimonies, as well as secondary material on the structure of the camp system, individual camp histories, and the resistance organizations within them. My primary sources of data are 249 Holocaust testimonies collected from three archives and content coded based on eight broad categories [arrival, labor, structure, guards, rules, abuse, culture, and resistance]. -

WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews

WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ excerpts from 18 Centropa interviews WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews As the most notorious death camp set up by the Nazis, the name Auschwitz is synonymous with fear, horror, and genocide. The camp was established in 1940 in the suburbs of Oswiecim, in German-occupied Poland, and later named Auschwitz by the Germans. Originally intended to be a concentration camp for Poles, by 1942 Auschwitz had a second function as the largest Nazi death camp and the main center for the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. Auschwitz was made up of over 40 camps and sub-camps, with three main sec- tions. The first main camp, Auschwitz I, was built around pre-war military bar- racks, and held between 15,000 and 20,000 prisoners at any time. Birkenau – also referred to as Auschwitz II – was the largest camp, holding over 90,000 prisoners and containing most of the infrastructure required for the mass murder of the Jewish prisoners. 90 percent of Auschwitz’s victims died at Birkenau, including the majority of the camp’s 75,000 Polish victims. Of those that were killed in Birkenau, nine out of ten of them were Jews. The SS also set up sub-camps designed to exploit the prisoners of Auschwitz for slave labor. The largest of these was Buna-Monowitz, which was established in 1942 on the premises of a synthetic rubber factory. It was later designated the headquarters and administrative center for all of Auschwitz’s sub-camps, and re-named Auschwitz III. All the camps were isolated from the outside world and surrounded by elec- trified barbed wire. -

Buchenwald Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 51°01′20″N 11°14′53″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Buchenwald concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 51°01′20″N 11°14′53″E "Buchenwald" redirects here. For other uses, see Buchenwald (disambiguation). Navigation Buchenwald concentration camp (German: Konzentrationslager (KZ) Buchenwald, IPA: Main page [ˈbuːxәnvalt]; literally, in English: beech forest) was a German Nazi concentration camp Contents established on the Ettersberg (Etter Mountain) near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937, one of Featured content the first and the largest of the concentration camps on German soil, following Dachau's Current events opening just over four years earlier. Random article Donate to Wikipedia Prisoners from all over Europe and the Soviet Union—Jews, non-Jewish Poles and Slovenes, the mentally ill and physically-disabled from birth defects, religious and political prisoners, Roma and Sinti, Freemasons, Jehovah's Witnesses, criminals, homosexuals, and prisoners of Interaction war — worked primarily as forced labor in local armaments factories.[1] From 1945 to 1950, Help the camp was used by the Soviet occupation authorities as an internment camp, known as About Wikipedia NKVD special camp number 2. Community portal Today the remains of Buchenwald serves as a memorial and permanent exhibition and Recent changes museum.[2] Contact Wikipedia Contents Toolbox 1 History 2 People What links here 2.1 Camp commandants Related changes 2.2 Female prisoners and overseers Upload file 2.3 Allied airmen Special pages 3 Death toll -

PDF Download

1 1. Frankfurter Auschwitz-Prozess »Strafsache gegen Mulka u.a.«, 4 Ks 2/63 Landgericht Frankfurt am Main 170. Verhandlungstag, 21.6.1965 und 171. Verhandlungstag, 25.06.1965 Plädoyer des Verteidigers Staiger für Hofmann Vorsitzender Richter: Ich darf nun Herrn Rechtsanwalt Doktor Staiger um seine Ausführungen bitten. Verteidiger Staiger: Herr Präsident, meine Damen und Herren Richter und Geschworenen, als mein Mandant Hofmann am 1.12.1942 zum KL Auschwitz kam, war dort, wie Herr Staatsanwalt Vogel zutreffend hervorhob, die Todesmaschinerie bereits voll im Gange. Die vom Führer und Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler schon 1941 befohlene und in der Wannsee-Konferenz von den Repräsentanten des Reichs und der Justiz widerspruchslos akzeptierte »Endlösung der Judenfrage« durch physische Vernichtung war eine von uns heute als unfaßbar angesehene Realität geworden. Hofmann erhielt die Stellung eines 3. Schutzhaftlagerführers zugewiesen, eine Funktion, die es bis dahin nicht gegeben hatte und die auch nach seiner Versetzung am 15. Mai 1944 nicht mehr existierte. Er war also zunächst innerhalb der SS-Hierarchie im Lager nicht Befehlsgeber, sondern Befehlsempfänger. Er ordnete nicht an, sondern führte Anordnungen des 1. Schutzhaftlagerführers Aumeier und des 2. Schutzhaftlagerführers Schwarz, nach der Versetzung Aumeiers des 1. Schutzhaftlagerführers Schwarz und des 2. Schutzhaftlagerführers Max Sell, denen er bis zum Beginn der Kommandantur durch den neuen Kommandanten Liebehenschel unterstellt war, aus. Die Stellung des 3. Schutzhaftlagerführers war praktisch überflüssig. Man hatte Hofmann von Dachau nach Auschwitz einfach abgeschoben, und zwar offensichtlich deshalb, weil er, wie ich später noch unter Beweis stellen werde, dem dortigen Kommandanten und dem Inspekteur der KL, SS- Obergruppenführer Glücks, durch seine Gesuche um Frontversetzung unliebsam geworden war. -

Wp Content/ Uploads/ 2016/ 03/ MOTL

SEARCH SAVE PDF TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS A Welcome and Introduction 1 B Acknowledgements 2 C To the Children... A Dedication 3 D Suggested Reading List 4 E This Study Guide and You 6 F My Journal - A Silent Dialogue with Myself 7 G Understanding Human Emotions 11 H Hurricane Andrew and the Holocaust 16 I You Are the Best 17 UNIT I - DANGER SIGNALS I Exploring Our Roots 19 II Prejudice and Discrimination 27 III A Study of Words 37 IV Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust 44 V "Vus is geven is geven" - What was lost is lost forever 53 UNIT II - THE PERSECUTION YEARS VI A State of Terror: Germany 1933-1939 70 VII The War against the Jews 79 VIII The Ghetto 95 IX The Camps 110 Study Guide X Living with Dignity in a World Gone Insane 133 XI The Silent World and the Righteous Few Who Did Respond 154 XII Poland Today 176 XIII PostScript 186 UNIT III - ISRAEL XIV Shivat Zion - The Return to Zion 196 XV The Yishuv - During the Shoah 206 XVI B'riha - The Illegal Immigration (1945-1947) 213 XVII The Struggle for Independence and the Birth of the State of Israel (1945-1948) 224 XVIII The War of Independence (1947-1949) 238 XIX Yom HaZikaron and Yom Ha'Atzmaut 254 XX Jerusalem 261 XXI The Legacy: The War of Independence and the Current Peace Process 269 HOME A. WELCOME Dear March of the Living Participant, You are about to embark upon an exciting experience, one that may just change your life. -

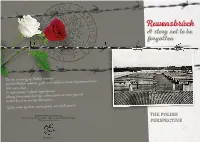

The Polish Perspective

Ravensbrück A story not to be forgotten To the memory of Polish women 40,000 Polish women, girls and children were imprisoned here 200 were shot 74 underwent medical experiments Many thousands died of malnutrition or were gassed 8,000 lived to see the liberation If the echo of their voices fades, we shall perish Institute of National Remembrance Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation The Szczecin Branch Office THE POLISH PERSPECTIVE Szczecin 2020 Sketch plan of the KL Ravensbrück camp Map of the Brandenburg Province with the location of the camp marked Ravensbrück A story not to be forgotten THE POLISH PERSPECTIVE Institute of National Remembrance Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation The Szczecin Branch Office Szczecin 2020 Text: Zbigniew Stanuch Translation: Mirosława Landowska Editing and proofreading: Klaudyna Michałowcz Graphic design and typesetting: Table of Contents Stilus Rajmund Dopierała Published in the online version Introduction � 5 Sources of iconographic materials: Archives of the Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw Camp authorities � 10 National Site of Admonition and Remembrance at Ravensbrück (Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück) Transports � 13 Cover and title page photographs: The layout of the camp � 20 The view of the barracks camp with barrack rows no. 1 and 2 of the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp at no. 1, Lagerstraße; The men’s camp in Ravensbrück � 28 in the foreground, the roof of the garage wing with chimneys of Living conditions and labour in the camp � 29 the inmates’ kitchen behind, ca. 1940. The photograph was taken from the Commandant’s Office building.