Contents Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Description Garden of Righteous Gentiles Wilmington DE

Garden of the Righteous Gentiles Siegel Jewish Community Center - Wilmington, Delaware The Garden of the Righteous Gentiles is the first monument in the United States to Christians who saved Jewish lives during the Nazi Holocaust in Europe. The Garden is patterned after the "Avenue of the Righteous'' at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum and resource center in Jerusalem. The Holocaust was the systematic mass murder of 6,000,000 Jews by the Nazis and their collaborators during the years 1933-1945. Few non-Jews risked their lives and the lives of their families to defy the murderous Nazis. The Christians honored here are among the heroes of human history. They risked their lives to save Jews from death during the Holocaust. By their actions, they demonstrated that love and decency could flourish amidst unthinkable barbarism. RIGHTEOUS GENTILES REMEMBERED IN THE GARDEN AMSTERDAM ARTIS ROYAL ZOO became a safe haven for many avoiding capture during the years of Nazi occupation of The Netherlands, including Francisca Verdoner Kan of Wilmington. Francisca’s parents sent her and her siblings into hiding after Nazis commandeered their home. She honors Amsterdam’s Artis Royal Zoo, where, as a child, Francisca spent many long days, while staff members hid hundreds of other Jews throughout the zoo, primarily in food storage lofts just above the animal cages. Hiding in these lofts was particularly dangerous, as the zoo was a popular recreation site for the occupying Germans. It was partly due to their frequent attendance, however, that allowed the zoo to remain in operation throughout the war and continually buy food, which not only sustained the animals, but those hiding above their cages as well. -

The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – a Guide to The

PUBLISHED BY Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial Jean-Dolidier-Weg 75 21039 Hamburg Phone: +49 40 428131-500 [email protected] www.kz-gedenkstaette-neuengamme.de EDITED BY Karin Schawe TRANSLATED BY Georg Felix Harsch PHOTOS unless otherwise indicated courtesy We would like to thank the Friends of of the Neuengamme Memorial‘s Archive the Neuengamme Memorial association and Michael Kottmeier for their financial support. Maps on pages 29 and 41: © by M. Teßmer, graphische werkstätten This brochure was produced with feldstraße financial support from the Federal Commissioner for Culture and the Media GRAPHIC DESIGN BY based on a decision by the Bundestag, Annrika Kiefer, Hamburg the German parliament. The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – PRINTED BY A Guide to the Site‘s History and the Memorial Druckerei Siepmann GmbH, Hamburg Hamburg, November 2010 The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – A Guide to the Site‘s History and the Memorial The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – A Guide to the Site's History and the Memorial Published by the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial Edited by Karin Schawe Contents 6 Preface 10 The NeueNgamme coNceNTraTioN camP, 1938 To 1945 12 chronicle of events, 1938 to 1945 20 The construction of the Neuengamme concentration camp 22 The Prisoners 22 German Prisoners 25 Prisoners from the Occupied Countries 30 The concentration camp SS 31 Slave Labour 35 housing 38 Death 40 The Satellite camps 42 The end 45 The Victims of the Neuengamme concentration camp 46 The SiTe afTer 1945 48 chronicle of events from 1945 58 The British internment camp 59 The Transit camp 60 The Prisons and the memorial at the historical Site of the concentration camp Contents 66 The NeueNgamme coNceNTraTioN camP memoriaL 70 The grounds 93 archives and Library 70 The house of commemoration 93 The Archive 72 The exhibitions 95 The Library 72 Main Exhibition Traces of History 96 The Open Archive 73 Research Exhibition Posted to Neuengamme. -

Dear Educator, Jehovah's Witnesses, a Christian Community of 35,000 In

Dear Educator, Jehovah’s Witnesses, a Christian community of 35,000 in Germany and occupied lands, refused to conform to the Nazi ideology of hate. They suffered severely for their belief in nonviolence and their utter rejection of racism. Students are fascinated to learn that the Nazis offered the Witnesses the chance for freedom if they would sign a document renouncing their faith. Very few signed. Thrown into Nazi camps, they became eyewitnesses of Nazi genocide. As historian John Toland wrote, this is “a story of human courage that must be heard.” The Arnold-Liebster Foundation’s website at www.alst.org is an extensive educational resource that includes: • How to arrange for an interactive Skype conference between Simone Arnold Liebster and your students. • Jehovah’s Witnesses Stand Firm Against Nazi Assault documentary DVD and study guide. Please contact me for a free copy of the DVD. • Realizing the importance of Holocaust education, the Arnold-Liebster Foundation is willing to subsidize a major part of the cost of their traveling exhibits. • Online lesson plans, study guides, primary documents, online exhibitions, survivor testimony, classroom questions, educator comments, and more. In North Carolina and South Carolina, contact Diana Zientek for more information at [email protected], 828-645-7138. Please feel free to contact me if you have any questions. Sincerely, Sandra S. Milakovich [email protected] Twitter: @arnoldliebster U.S. Representative: 4004 Rodeo Road · Davenport, IA 52806 · 563.391.1819 · alst.org DACHAU PRINCIPAL DISTINGUISHING BADGES WORN BY PRISONERS 3 2 6 7 8 Political Criminal Antisocial Homosexual Emigrant Jehovah’s Witness Jewish Jewish Jewish Jewish Jewish Political Criminal Antisocial Homosexual Emigrant F Political Political Penal Wehrmacht Prisoners (French) Second-time Company Prisoners Under Special Offenders Surveillance Berben, Paul. -

Albert Halper's “Prelude”

p rism • an interdisciplinaryan journal interdisciplinary for holocaust educators journal for holocaust educators • a rothman foundation publication an interdisciplinary journal for holocaust educators editors: Dr. karen shawn, Yeshiva University, nY, nY Dr. jeffreY Glanz, Yeshiva University, nY, nY editorial Board: Dr. Aden Bar-tUra, Bar-Ilan University, Israel yeshiva university • azrieli graduate school of jewish education and administration DarrYle Clott, Viterbo University, la Crosse, wI Dr. keren GolDfraD, Bar-Ilan University, Israel Brana GUrewItsCh, Museum of jewish heritage– a living Memorial to the holocaust, nY, nY Dr. DennIs kleIn, kean University, Union, NJ Dr. Marcia saChs Littell, school of Graduate studies, spring 2010 the richard stockton College of new jersey, Pomona volume 1, issue 2 Carson PhIllips, York University, toronto, Ca i s s n 1 9 4 9 - 2 7 0 7 Dr. roBert rozett, Yad Vashem, jerusalem, Israel Dr. David Schnall, Yeshiva University, nY, nY Dr. WillIaM shUlMan, Director, association of holocaust organizations Dr. samuel totten, University of arkansas, fayetteville Dr. WillIaM YoUnGloVe, California state University, long Beach art editor: Dr. PnIna rosenBerG, technion, Israel Institute of technology, haifa poetry editor: Dr. Charles AdÈs FishMan, emeritus Distinguished Professor, state University of new York advisory Board: stePhen feInBerG, United states holocaust Memorial Museum, washington, D.C. Dr. leo GoldberGer, Professor emiritus, new York University, nY Dr. YaaCoV lozowick, historian YItzChak MaIs, historian, Museum Consultant GerrY Melnick, kean University, NJ rabbi Dr. BernharD rosenBerG, Congregation Beth-el, edison; NJ Mark sarna, second Generation, real estate Developer, attorney Dr. David SilBerklanG, Yad Vashem, jerusalem, Israel spring 2010 • volume 1, issue 2 Simcha steIn, historian Dr. -

O Holocaustu Mailto:[email protected] Tel.:+420 774 685 370

Marek Šlechta: Filmy o holocaustu mailto:[email protected] tel.:+420 774 685 370 hraných 230 filmů o holocaustu Přehled hraných filmů o holocaustu a co v nich chybí Marek Šlechta květen 2014 1 Marek Šlechta: Filmy o holocaustu mailto:[email protected] tel.:+420 774 685 370 1. Úvod: Jak vnímám hrané filmy o holocaustu a jak jsem se naučil jíst hořké olivy Mému zájmu o umělecké ztvárnění holocaustu ve filmu (ó, jak strašné označení zájmu) předcházel dlouhodobý osobní niterný zájem o Izrael jakožto fenomén, tedy nejen o zemi současnou, historickou, národ Bible, centrum politického dění, nositele udržovatele a vizionáře kultury, průmyslu a náboženství, ale především o lidi, kteří žijí u nás v ČR, v Evropě, Izraeli, Americe i jinde na světě a jejichž život nějak souvisí s Izraelem. Patřím ke generaci, která v hodinách dějepisu neslyšela ani jednou slovo holocaust nebo pojem “vyvražďování Židů za Druhé světové války”, a to ani na základní, ani na střední ani na vysoké škole. Komunistický režim tehdejšího Československa promítl svůj antisemitismus do vzdělávacího systému tak, že existenci milionů obětí genocidy jednoho evropského národa prostě ignoroval. Mé prozření nastávalo postupně od roku 1985, když jsem se setkával s pamětníky, kteří přežili koncentrační tábory. Byli to přátelé naší rodiny v Pardubicích a Východních Čechách, kantor brněnské synagogy pan Arnošt Neufeld, členové Společnosti přátel Izraele v Pardubicích, Praze a Valašském Meziříčí, členové kibucu Kefar Masaryk a mnoho dalších lidí v Izraeli včetně herečky Nava Shean (Vlasta Schönová) a spisovatelů Avigdora Dagana (Viktora Fischla) a Arnošta Lustiga, v neposlední řadě také přednášející pamětnice o holocaustu paní Dr. -

Jehovah's Witnesses in National Socialist Concentration Camps, 1933

Religion, State & Society, Vol. 34, No. 2, June 2006 Jehovah’s Witnesses in National Socialist Concentration Camps, 1933 – 45* JOHANNES S. WROBEL Introduction With thousands incarcerated in the prisons and concentration camps of the ‘Third Reich’, Jehovah’s Witnesses, or Ernste Bibelforscher (Earnest Bible Students), were among the main and earliest victim groups of the terror apparatus of the National Socialists between 1933 and 1945. The Watchtower History Archive of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Selters/Taunus, Germany (WTA, Zentralkartei), has thus far registered a total of over 4200 names of male (2900) and female (1300) believers of different nationalities who went through a National Socialist concentration camp by the end of the regime in 1945.1 Between 1933 and 1935/36 members of this Christian faith were sent to official early camps, and then in far greater numbers to the newly established ‘modern’ main concentration camps (Stammlager), such as Sachsenhausen (1936), Buchenwald (1937) and Ravensbru¨ ck (1939). A total of 2800 males and females went through these three camps alone by 1945. Allegedly enemies of the state, the Witnesses proved, as historian Christine King (1982, p. 169) has observed, to be ‘a small but memorable band of prisoners, marked by the violet triangle and noted for their courage and their convictions’. When the concentration camp system was reorganised in 1936, the SS administra- tion, controlled by Heinrich Himmler,2 introduced an elaborate classification of prisoners by means of badges with triangles and with black, green, pink, purple and red colours. Jehovah’s Witnesses in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp were assigned the purple triangle in July 1936 (Eberle, 2005, p. -

Notes to Accompany the Powerpoint

Rescuers, A Model for a Caring Community Notes to accompany the PowerPoint. Birmingham Holocaust Education Center December 2009 1 Slide 1: TITLE SLIDE Rescuers are those who, at great personal risk, actively helped members of persecuted groups, primarily Jews, during the Holocaust in defiance of Third Reich policy. They were ordinary people who became extraordinary people because they acted in accordance with their own belief systems while living in an immoral society. Righteous Gentiles is also a term used for rescuers. “Gentiles” refers to people who are not Jewish. The most salient fact about the rescues was the fact that it was rare. And, these individuals who risked their lives were far outnumbered by those who took part in the murder of the Jews. These rescuers were even more outnumbered by those who stood by and did nothing. Yet, this aspect of history certainly should be taught to highlight the fact that the rescuers were ordinary people from diverse backgrounds who held on to basic values, who undertook extraordinary risks. The rescuers were people who before the war began were not saving lives or risking their own to defy unjust laws. They were going about their business and not necessarily in the most principled manner. Thus, we ask the question: “what is the legacy of these rescuers that impact our lives and guide us in making our world a better place.” 2 Slide 2 Dear Teacher: I am a survivor of a concentration camp. My eyes saw what no man should witness: Gas chambers built by learned engineers, Children poisoned by educated physicians, Infants killed by trained nurses, Women and babies shot and burned by high school and college graduates, So I am suspicious of education. -

Wp Content/ Uploads/ 2016/ 03/ MOTL

SEARCH SAVE PDF TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS A Welcome and Introduction 1 B Acknowledgements 2 C To the Children... A Dedication 3 D Suggested Reading List 4 E This Study Guide and You 6 F My Journal - A Silent Dialogue with Myself 7 G Understanding Human Emotions 11 H Hurricane Andrew and the Holocaust 16 I You Are the Best 17 UNIT I - DANGER SIGNALS I Exploring Our Roots 19 II Prejudice and Discrimination 27 III A Study of Words 37 IV Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust 44 V "Vus is geven is geven" - What was lost is lost forever 53 UNIT II - THE PERSECUTION YEARS VI A State of Terror: Germany 1933-1939 70 VII The War against the Jews 79 VIII The Ghetto 95 IX The Camps 110 Study Guide X Living with Dignity in a World Gone Insane 133 XI The Silent World and the Righteous Few Who Did Respond 154 XII Poland Today 176 XIII PostScript 186 UNIT III - ISRAEL XIV Shivat Zion - The Return to Zion 196 XV The Yishuv - During the Shoah 206 XVI B'riha - The Illegal Immigration (1945-1947) 213 XVII The Struggle for Independence and the Birth of the State of Israel (1945-1948) 224 XVIII The War of Independence (1947-1949) 238 XIX Yom HaZikaron and Yom Ha'Atzmaut 254 XX Jerusalem 261 XXI The Legacy: The War of Independence and the Current Peace Process 269 HOME A. WELCOME Dear March of the Living Participant, You are about to embark upon an exciting experience, one that may just change your life. -

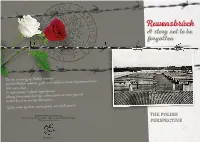

The Polish Perspective

Ravensbrück A story not to be forgotten To the memory of Polish women 40,000 Polish women, girls and children were imprisoned here 200 were shot 74 underwent medical experiments Many thousands died of malnutrition or were gassed 8,000 lived to see the liberation If the echo of their voices fades, we shall perish Institute of National Remembrance Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation The Szczecin Branch Office THE POLISH PERSPECTIVE Szczecin 2020 Sketch plan of the KL Ravensbrück camp Map of the Brandenburg Province with the location of the camp marked Ravensbrück A story not to be forgotten THE POLISH PERSPECTIVE Institute of National Remembrance Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation The Szczecin Branch Office Szczecin 2020 Text: Zbigniew Stanuch Translation: Mirosława Landowska Editing and proofreading: Klaudyna Michałowcz Graphic design and typesetting: Table of Contents Stilus Rajmund Dopierała Published in the online version Introduction � 5 Sources of iconographic materials: Archives of the Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw Camp authorities � 10 National Site of Admonition and Remembrance at Ravensbrück (Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück) Transports � 13 Cover and title page photographs: The layout of the camp � 20 The view of the barracks camp with barrack rows no. 1 and 2 of the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp at no. 1, Lagerstraße; The men’s camp in Ravensbrück � 28 in the foreground, the roof of the garage wing with chimneys of Living conditions and labour in the camp � 29 the inmates’ kitchen behind, ca. 1940. The photograph was taken from the Commandant’s Office building. -

Quarterly 2 · 2010

German Films Quarterly 2 · 2010 IN CANNES: UN CERTAIN REGARD THE CITY BELOW by Christoph Hochhaeusler LIFE, ABOVE ALL by Oliver Schmitz PORTRAITS Directors Brigitte Bertele & Robert Thalheim, Collina Film Production, Actor Volker Bruch In Competition MY JOY by Sergei Loznitsa German Producer: ma.ja.de fiction/Leipzig World Sales: Fortissimo Film Sales/Amsterdam In Competition LA PRINCESSE DE MONTPENSIER by Bertrand Tavernier German Producer: Pandora Film/Cologne World Sales: StudioCanal/Paris In Competition TENDER SON – THE FRANKENSTEIN PROJECT by Kornél Mundruczó German Producer: Essential Filmproduktion/Berlin World Sales: Coproduction Office/Paris In Competition TOURNÉE by Mathieu Amalric German Producer: Neue Mediopolis Filmproduktion/Leipzig World Sales: Le Pacte/Paris In Competition UNCLE BOONMEE WHO CAN RECALL HIS PAST LIVES by Apichatpong Weerasethakul German Producers: Geissendoerfer Film- und Fernsehproduktion & The Match Factory/Cologne World Sales: The Match Factory/Cologne Out of Competition THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF NICOLAE CEAUSESCU by Andrei Ujicaˇ German Producer: Neue Mira Filmproduktion/Bremen World Sales: Mandragora International/Paris Out of Competition CARLOS THE JACKAL by Olivier Assayas German Producer: Egoli Tossell Film/Halle World Sales: StudioCanal/Paris Un Certain Regard AURORA by Cristi Puiu German Producer: Essential Filmproduktion/Berlin World Sales: Coproduction Office/Paris GERMAN FILMS AND CO-PRODUCTIONS 2010 FILM FESTIVAL THE CANNES AT Un Certain Regard THE CITY BELOW by Christoph Hochhaeusler Producer: Heimatfilm/Cologne -

Speak up Speak Out

Northwood Holocaust Memorial Day Events Speak Up Speak Out Teachers’ Resource Pack Monday 1st February to Thursday 4th February 2010 2014 Edition ‘.. and the bush was burned with fire Photograph courtesy of Weiner Library, London but was not consumed’ Exodus 3:2 NHMDENHMDE Resistance Resistance and and Rescuers Rescuers in in the the Holocaust Holocaust ContentsContents •• President President Barak Barak Obama’s Obama’s Holocaust Holocaust Memorial Memorial DayDay address address In In Washington, Washington, 2009 2009 •• Notes Notes for for Teachers Teachers •• PowerPoint PowerPoint Presentation; Presentation; Resistance Resistance and and RescuersRescuers in in the the Holocaust Holocaust •• Lesson Lesson plans: plans: •• around around Rescuers Rescuers •• student student research research project project on on Resistance Resistance in in the the Holocaust Holocaust •• Significant Significant datesdates in in the the HolocaustHolocaust •• Glossary Glossary •• Websites Websites •• Acknowledgements Acknowledgements WeWe hope hope this this pack pack will will enable enable your your students students to to prepare prepare for for their their visitvisit to to this this event. event. If If you you wish wish to to download download further further copies copies of of this this materialmaterial please please visit visit www.northwoodhmd.org.uk. www.northwoodhmd.org.uk. If If you you have have further further questionsquestions please please call call tel: tel: 08456 08456 448 448 006 006 fax: fax: 01923 01923 820357. 820357. WeWe look look -

1942 Other Victims of Nazi Crimes Scenario

OTHER VICTIMS subject OF NAZI CRIMES Context8. According to the Nazi ideology, Jews into two categories: ‘worthy’ individuals constituted the greatest threat to Ger- (enjoying full civic rights) and those man society and racial purity. For this rea- ‘useless’ not only denied equal rights, but son, their rights were gradually limited with primarily the right to live. isolation in designated areas after the war broke out. Then, they were murdered in death Several months after the Nazis gained power, camps and other murder sites. a law was enacted on 14 July 1933 ‘to prevent the birth of offspring with hereditary diseases’. However, Jews were not the only group persecuted Over time, that regulation was used to forcibly by the Nazis. Even before the Second World War sterilise people with mental illnesses and those had begun, they sought to ‘purify’ German society suffering from epilepsy, deafness, blindness and from all ‘racially different’ groups (to which Sinti physical deformities. That group also included and Roma belonged, alongside Jews), as well as alcohol addicts, who were subject forced persons with physical disabilities, mental-health sterilisation. According to estimates, between difficulties and ones considered to be anti-social. 200,000 and 380,000 persons underwent the The last-mentioned group included homosexuals treatment pursuant to that law by 1938. However, and prostitutes and, given their nomadic lifestyle, no attempts were made to murder them before Sinti and Roma. Political opponents (mainly the Second World War. A certain type of exception socialists and communists as well as various and impulse toward adopting such a decision later union and social activists opposed to the Nazis) in the autumn of 1939 was a certain Kretschmar constituted a separate category.