Quantity Over Quality?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2010 2 Traction Annual Report 2010 Shareholder Information

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 2 TRACTION ANNUAL REPORT 2010 SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION Ankarsrum Assistent AB SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION 2011 May 9 Interim Report for the period January – March May 9 Annual General Meeting 2011 July 21 Interim Report for the period January – June October 27 Interim Report for the period January – September Subscription to financial information via e-mail may be made at traction.se, or by e-mail to [email protected]. All reports during the year will be available at the Company’s website. Traction’s official annual accounts are available for downloading at the website well before the Annual General Meeting. TRACTION ANNUAL REPORT 2010 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS 4 2010 SUMMARY 6 PRESIDENT’S STATEMENT 8 TRACTION’S BUSINESS 1 5 BUSINESS ORGANISATION 16 LISTED ACTIVE HOLDINGS 19 UNLISTED ACTIVE HOLDINGS 23 SUBSIDIARIES 26 OWNERSHIP POLICY 28 TRACTION FROM AN INVESTOR PERSPECTIVE 32 A SMALL SELECTION OF TRANSACTIONS OVER THE PAST TEN YEARS 36 THE TRACTION SHARE 38 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 3 9 ADDRESSES Nilörngruppen AB 4 TRACTION ANNUAL REPORT 2010 TRACTION IN BRIEF 2010 SUMMARY • Profit after taxes amounted to MSEK 206 (SEK 12.11 per share). • The change in value of securities was MSEK 110 (267). • Operating profit in the operative subsidiaries amounted to MSEK 67 (–13). • Underwriting of new issues in Switchcore, Rörvik Timber, PA Resources and Alm Brand, which generated revenue of MSEK 15.5 (7.8). • The return on equity was 15 (25) %. • Equity per share amounted to SEK 95 (85). • Sharp increases in profit of Nilörngruppen and Ankarsrum Motors. • Traction’s liquid capacity for new, active engagements amounts to MSEK 800. -

Purchase and Sales by Report Date Composite

Purchase and Sales by Report Date Composite July 1, 2013 to July 31, 2013 View Date: August 8, 2013 Funds Included in Composite NJBD COMMON D EMERGING NJBU COMMON D DEVELOPED NJDE COMMON D DEVELOPED PASSIVE NJDO COMMON D DEVELOPED ETFS NJDU COMMON D HEALTHCARE NJDV COMMON D TECHNOLOGY NJDZ COMMON D OAC NJEA COMMON D EMERGING MORGAN STNLY NJEB COMMON D EMERGING LAZARD NJED COMMON D EMERGING PICTET NJEM COMMON D EMERGING WELLINGTON Page 1 Prepared by State Street Purchase Report by Report Date Composite July 1, 2013 to July 31, 2013 View Date: August 8, 2013 Base Currency: USD - US DOLLAR Asset ID Security Name/Description Trd Date Stl Date Fail Days Broker Name Stl Cur/Loc Comm Per Shr Shares/Par/Contracts Exchange Rate Fund Price Interest Commissions Taxes/Fees/Other Net Cost Units/Original Face CASH EQUIVALENTS US DOLLAR 85749P9B9 STATE STR INSTL LIQUID RESVS 0.093% 31 Dec 2099 01 Jul 2013 01 Jul 2013 STATE STREET BANK AND TRUST USD/CSW 744,135.040 1.000000 NJEM Local 100.000000 0.00 0.00 0.00 744,135.04 Base 100.000000 0.00 0.00 0.00 744,135.04 85749P9B9 STATE STR INSTL LIQUID RESVS 0.093% 31 Dec 2099 01 Jul 2013 01 Jul 2013 STATE STREET BANK AND TRUST USD/CSW 592,948.130 1.000000 NJEA Local 100.000000 0.00 0.00 0.00 592,948.13 Base 100.000000 0.00 0.00 0.00 592,948.13 85749P9B9 STATE STR INSTL LIQUID RESVS 0.093% 31 Dec 2099 01 Jul 2013 01 Jul 2013 STATE STREET BANK AND TRUST USD/CSW 478,031.100 1.000000 NJEB Local 100.000000 0.00 0.00 0.00 478,031.10 Base 100.000000 0.00 0.00 0.00 478,031.10 85749P9B9 STATE STR INSTL LIQUID RESVS -

Annual and Sustainability Report 2020 Content

BETTER CONNECTED LIVING ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2020 CONTENT OUR COMPANY Telia Company at a glance ...................................................... 4 2020 in brief ............................................................................ 6 Comments from the Chair ..................................................... 10 Comments from the CEO ...................................................... 12 Trends and strategy ............................................................... 14 DIRECTORS' REPORT Group development .............................................................. 20 Country development ........................................................... 38 Sustainability ........................................................................ 48 Risks and uncertainties ......................................................... 80 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Corporate Governance Statement ......................................... 90 Board of Directors .............................................................. 104 Group Executive Management ............................................ 106 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Consolidated statements of comprehensive income ........... 108 Consolidated statements of financial position ..................... 109 Consolidated statements of cash flows ............................... 110 Consolidated statements of changes in equity .................... 111 Notes to consolidated financial statements ......................... 112 Parent company income statements ................................... -

College Retirement Equities Fund

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2010-05-27 | Period of Report: 2010-03-31 SEC Accession No. 0000930413-10-003160 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER COLLEGE RETIREMENT EQUITIES FUND Mailing Address Business Address 730 THIRD AVE 730 THIRD AVE CIK:777535| IRS No.: 136022042 | State of Incorp.:NY | Fiscal Year End: 1231 NEW YORK NY 10017 NEW YORK NY 10017 Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-04415 | Film No.: 10861628 2129164905 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number File No. 811-4415 COLLEGE RETIREMENT EQUITIES FUND (Exact name of Registrant as specified in charter) 730 Third Avenue, New York, New York 10017-3206 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Stewart P. Greene, Esq. c/o TIAA-CREF 730 Third Avenue New York, New York 10017-3206 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrants telephone number, including area code: 212-490-9000 Date of fiscal year end: December 31 Date of reporting period: March 31, 2010 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Item 1. Schedule of Investments. COLLEGE RETIREMENT EQUITIES FUND - Stock Account COLLEGE RETIREMENT EQUITIES FUND STOCK ACCOUNT SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS (unaudited) March 31, 2010 MATURITY VALUE PRINCIPAL ISSUER RATE RATING DATE (000) BONDS - 0.0% CORPORATE BONDS - 0.0% HOLDING AND OTHER INVESTMENT OFFICES - 0.0% $ 100,000,000 j Japan Asia Investment Co Ltd 0.000% 09/26/11 NR $ 535 22,970 Kiwi Income Property Trust 8.950 12/20/14 NR 17 TOTAL HOLDING AND OTHER INVESTMENT OFFICES 552 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. -

Telia Company – Annual and Sustainability Report 2019

BRINGING THE WORLD CLOSER ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2019 CONTENT OUR COMPANY Telia Company in one minute ................................................ 4 2019 in brief ............................................................................ 6 How we create value ............................................................. 8 Comments from the CEO ..................................................... 10 Trends and strategy .............................................................. 12 DIRECTORS' REPORT Group development ............................................................. 16 Country development .......................................................... 32 Sustainability ....................................................................... 41 Risks and uncertainties ....................................................... 62 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Corporate Governance Statement ....................................... 70 Board of Directors ............................................................... 82 Group Executive Management ............................................ 84 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Consolidated statements of comprehensive income .......... 86 Consolidated statements of financial position .................... 87 Consolidated statements of cash flows .............................. 88 Consolidated statements of changes in equity ................... 89 Notes to consolidated financial statements ........................ 90 Parent company income statements.................................. 182 Parent company -

Investment AB Kinnevik

Investment AB Kinnevik Skeppsbron 18 (Publ) Reg no 556047-9742 P.O. Box 2094 Phone +46 8 562 000 00 SE-103 13 Stockholm Sweden Fax +46 8 20 37 74 www.kinnevik.se BOKSLUTSKOMMUNIKÉ 2007 Finansiell utveckling under fjärde kvartalet • Marknadsvärdet på koncernens aktier i Noterade Kärninnehav steg med 6.241 Mkr och uppgick per 31 december till 50.761 Mkr. • Korsnäs intäkter uppgick till 1.821 (1.722) Mkr. • Rörelseresultatet för Korsnäs var 7 (78) Mkr (jämförelsetal exklusive omstruktureringskostnader). • Koncernens totala intäkter uppgick till 1.873 (1.767) Mkr och rörelseresultatet var -5 (-124) Mkr. • Resultat efter skatt, inklusive förändring i verkligt värde av finansiella tillgångar, uppgick till 6.647 (9.192) Mkr. • Resultat per aktie uppgick till 25,18 (34,82) kronor. Händelser under fjärde kvartalet • Koncernen deltog i Black Earth Farmings nyemission. Kinnevik ägde vid årets utgång 20% av bolaget. Finansiell utveckling under 2007 • Marknadsvärdet på koncernens aktier i Noterade Kärninnehav ökade med 14.606 Mkr, motsvarande 40%, till 50.761 Mkr den 31 december. • Korsnäs intäkter ökade med 5% till 7.519 (7.134) Mkr (jämförelsetal proforma inklusive Frövi). • Rörelseresultatet för Korsnäs var 836 (865) Mkr (jämförelsetal proforma inklusive Frövi, exklusive omstruktureringskostnader). • Koncernens totala intäkter uppgick till 7.673 (6.305) Mkr och rörelseresultatet var 885 (478) Mkr. • Resultat efter skatt, inklusive förändring i verkligt värde av finansiella tillgångar, uppgick till 16.179 (11.549) Mkr. • Resultat per aktie uppgick till 61,29 (43,74) kronor. • Styrelsen föreslår att årsstämman beslutar om en kontantutdelning om 2,00 (1,70) kronor per aktie. Därutöver avser styrelsen att rekommendera till Kinneviks årsstämma som hålls den 15 maj att besluta om ett förnyat mandat att återköpa maximalt 10% av bolagets egna aktier. -

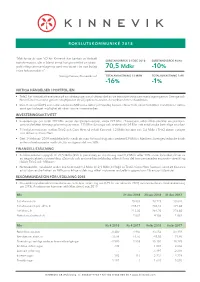

70,5 Mdkr -10% -16%

BOKSLUTSKOMMUNIKÉ 2018 ”Mitt första år som VD för Kinnevik har kantats av fortsatt SUBSTANSVÄRDE 31 DEC 2018 SUBSTANSVÄRDE Kv/Kv transformation, där vi bland annat har genomfört en strate- giskt viktig sammanslagning samt investerat i tio nya bolag 70,5 Mdkr -10% i våra fokusområden” Georgi Ganev, Kinneviks vd TOTALAVKASTNING 12 MÅN TOTALAVKASTNING 5 ÅR -16% -1% VIKTIGA HÄNDELSER I PORTFÖLJEN • Tele2 har fortsatt att exekvera på sin strategi genom slutförandet av de transformativa sammanslagningarna i Sverige och Nederländerna samt genom utnyttjandet av säljoptionen avseende verksamheten i Kazakstan • Den 9 Januari 2019 sekundärnoterades Millicoms aktier på Nasdaq-börsen i New York, vilket förbättrar likviditeten i aktien samt ger bolaget möjlighet att nå en större investerarbas INVESTERINGSAKTIVITET • Investeringar om totalt 392 Mkr under det fjärde kvartalet, varav 227 Mkr i Travelperk, vilka tillhandahåller en plattform som underlättar företags planering av resor, 111 Mkr i Livongo och resterande 54 Mkr i ett antal andra befntliga innehav • Till följd av fusionen mellan Tele2 och Com Hem så erhöll Kinnevik 1,2 Mdkr kontant och 3,6 Mdkr i Tele2 aktier, i utbyte mot aktierna i Com Hem • Den 14 februari 2019 meddelade Kinnevik att man förbundit sig att investera 0,9 Mdkr i MatHem, Sveriges ledande fristå- ende onlinebaserade matbutik, för en ägarandel om 38% FINANSIELL STÄLLNING • Substansvärdet uppgick till 70,5 Mdkr (256 kr per aktie), en minskning med 8,2 Mdkr eller 10% under kvartalet, drivet av en negativ aktiekursutveckling i Zalando och andra e-handelsbolag vilken till viss del kompenserades av positiv utveckling i både Tele2 och Millicom • Nettoskulden minskade under kvartalet med 1,2 Mdkr till 2,9 Mdkr, till följd av Tele2 / Com Hem fusionen samt att Kinnevik erhöll den andra halvan av Millicoms årliga utdelning, vilket motsvarar en belåningsgrad om 4% av portföljvärdet REKOMMENDATION FÖR UTDELNING 2018 • Kinneviks styrelse rekommenderar en ordinarie utdelning om 8,25 kr per aktie för 2018 motsvarande en direktavkastning om 3,9%. -

Thomson One Symbols

THOMSON ONE SYMBOLS QUICK REFERENCE CARD QUOTES FOR LISTED SECURITIES TO GET A QUOTE FOR TYPE EXAMPLE Specific Exchange Hyphen followed by exchange qualifier after the symbol IBM-N (N=NYSE) Warrant ' after the symbol IBM' When Issued 'RA after the symbol IBM'RA Class 'letter representing class IBM'A Preferred .letter representing class IBM.B Currency Rates symbol=-FX GBP=-FX QUOTES FOR ETF TO GET A QUOTE FOR TYPE Net Asset Value .NV after the ticker Indicative Value .IV after the ticker Estimated Cash Amount Per Creation Unit .EU after the ticker Shares Outstanding Value .SO after the ticker Total Cash Amount Per Creation Unit .TC after the ticker To get Net Asset Value for CEF, type XsymbolX. QRG-383 Date of issue: 15 December 2015 © 2015 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. Thomson Reuters disclaims any and all liability arising from the use of this document and does not guarantee that any information contained herein is accurate or complete. This document contains information proprietary to Thomson Reuters and may not be reproduced, transmitted, or distributed in whole or part without the express written permission of Thomson Reuters. THOMSON ONE SYMBOLS Quick Reference Card MAJOR INDEXES US INDEXES THE AMERICAS INDEX SYMBOL Dow Jones Industrial Average .DJIA Airline Index XAL Dow Jones Composite .COMP AMEX Computer Tech. Index XCI MSCI ACWI 892400STRD-MS AMEX Institutional Index XII MSCI World 990100STRD-MS AMEX Internet Index IIX MSCI EAFE 990300STRD-MS AMEX Oil Index XOI MSCI Emerging Markets 891800STRD-MS AMEX Pharmaceutical Index -

GENDER EQUALITY in EUROPE Assessing 255 Leading Companies on Workplace Equality

GENDER EQUALITY IN EUROPE Assessing 255 leading companies on workplace equality SPECIAL REPORT MARCH 2020 Equileap is the leading organisation providing No part of this report may be reproduced data and insights on gender equality in the in any manner without the prior written corporate sector. We research and rank permission of Equileap. Any commercial use over 3,500 public companies around the of this material or any part of it will require world using a unique and comprehensive a license. Those wishing to commercialise Gender Equality ScorecardTM across 19 the use should contact Equileap at criteria, including the gender balance of the [email protected]. workforce, senior management and board of directors, as well as the pay gap, parental leave and sexual harassment. This Report is part of a project funded by the Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme of the Eu- ropean Union (2014-2020). CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................6 KEY FINDINGS.....................................................................................................................................7 Category A / Gender balance in Leadership & Workforce........................................9 Category B / Equal Compensation & Work-life Balance.............................................10 Category C / Policies Promoting Gender Equality...........................................................11 Category D / Commitment, Transparency & Accountability.......................................12 -

Årsredovisning 2011 CDON Group AB NASDAQ OMX Stockholm: CDON

Narva CDON GR CDON O UP AB ÅRSRE DO VIS N I NG 2011 Årsredovisning 2011 CDON Group AB NASDAQ OMX Stockholm: CDON CDON Group AB Bergsgatan 20 Box 385 CDON GROUP AB 54 % NETTOOMSÄTTNING 3 404 Mkr RÖRELSERESULTAT 201 23 Malmö www.cdongroup.com FÖRVÄRV AV RUM21 AB LANSERING AV MEMBERS.COM FÖRVÄRV AV TRETTI AB LANSERING AV NELLY.COM PÅ 20 NYA MARKNADER LANSERING AV CDON Group AB Årsredovisning 20112011 CDON Group AB Årsredovisning 2011 Innehållsförteckning Innehållsförteckning VD har ordet 1 VD har ordet 1 Ansvarstagande 3 Ansvarstagande 3 Finansiell översikt 6 Finansiell översikt 6 Förvaltningsberättelse 7 Förvaltningsberättelse 7 Bolagsstyrning 28 Bolagsstyrning 28 Styrelse 37 Styrelse 37 Verkställande ledning 41 Verkställande ledning 41 Koncernens räkenskaper 44 Koncernens räkenskaper 44 Moderbolagets räkenskaper 49 Moderbolagets räkenskaper 49 Noter 54 Noter 54 Underskrifter 92 Underskrifter 92 Revisionsberättelse 93 Revisionsberättelse 93 Definitioner 95 Definitioner 95 Produktion: Narva Tryck: Elanders CDON Group AB 1 Årsredovisning 2011 CDON Group AB ÅrsredovisningÖkad tillväxttakt 2011 och stärkt resultat ÖkadVD har ordet tillväxttakt och stärkt resultat VD har ordet CDON Group har haft en fantastisk utveckling och 2011 var inget undantag. Vårt första fullständiga år som en fristående e-handelskoncern på Nasdaq OMX CDONStockholm Group prägla har haftdes aven sortimentsu fantastisk utvecklingtveckling, ochgeografisk 2011 var expansion inget undantag. samt Vårt förstaförvärv fullständiga och lansering år somav ny ena verksamhetfristående eer-handelskoncern. Årets resultat ärpå samtidigt Nasdaq OMX vårt Stockholmstarkaste någonsin präglades med av sortimentsubåde accelereradtveckling, tillväxt geografisk och stärkt expansion lönsamhet samt. Det är förvärvett kvitto och på lansering att vår strategi av nya fungerar.verksamhet er. -

Annual Report 2009 ”More Than Seventy Years of Entrepreneurial Tradition Under the Same Group of Principal Owners” Contents

Annual Report 2009 ”More than seventy years of entrepreneurial tradition under the same group of principal owners” Contents Five-year Summary 3 Chief Executive’s review 4 Board of Directors 6 Senior Executives 8 Historical background 9 The Kinnevik share 10 Corporate Responsibility 12 Book and fair value of assets 15 Our Group 16 Proportional part of revenue and result 18 Major Unlisted Holdings Korsnäs 19 Major Listed Holdings Millicom 23 Tele2 24 Modern Times Group MTG 25 Metro 26 Transcom 26 New Ventures 27 Corporate Governance Report 30 Annual and Consolidated Accounts for 2009 Board of Directors’ Report 33 Financial Statements and Notes for the Group 37 Financial Statements and Notes for the Parent Company 63 Audit Report 70 Definitions of financial key ratios 71 Five-year Summary (SEK million) 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 Key Ratios Operating margin, % 10,0 5.2 11.5 7.6 7.6 Capital employed 50 462 33 067 59 778 44 629 31 022 Return on captial employed, % 40.1 -54.5 32.0 31.6 15.9 Return on shareholders' equity, % 50.2 -69.8 38.2 40.0 18.9 Equity/assets ratio, % 78 66 80 72 70 Net debt 8 233 8 906 9 205 9 856 7 249 Debt/equity ratio, multiple 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.3 0.3 Risk capital ratio, % 80.4 69.0 82.2 75.3 72.3 Total assets 53 240 35 871 62 818 47 733 32 122 Net asset value 44 829 24 325 54 941 39 168 25 717 Net asset value per share, SEK 162 93 208 148 97 Closing price, class B share, SEK 107 63 147 115 74 Market capitalization 29 656 16 410 38 739 30 358 19 535 Market value, Major Unlisted Holdings 10 232 8 026 11 659 11 559 6 131 Market -

Women Ceos Choose Gender Equality WOMEN Ceos CHOOSE GENDER EQUALITY 3 Nine out of Ten Companies Stuck with Men

THE ALLBRIGHT REPORT SEPTEMBER 2017 Women CEOs choose gender equality WOMEN CEOs CHOOSE GENDER EQUALITY 3 Nine out of ten companies stuck with men The proportion of women in senior positions population having a foreign background. The figure should has increased by merely a percentage point be significantly higher assuming that competence is evenly since AllBright’s last report. It’s not even worth distributed between people with foreign backgrounds considering progress. Around 85 per cent of and non-foreign backgrounds. CEOs who care about companies are still dominated by men and thus justice and profit should urgently recruit more diverse and hindering improvement. gender-balanced teams. The AllBright report 2017 shows modest progress. The In order to overcome the minimal progress, AllBright proportion of women increases by a percentage point from calls for a boycott of companies that reject women. Leave last year, reaching 21 per cent. The same bleak result is hypocrite companies in favour of companies ready to seen in CEO positions where women are stuck at six per embrace women’s competence. Move savings from unequal cent. Those believing in rapid change towards gender to equal companies for better price development. Use equality must be disappointed. consumer power to ditch male dominated companies. Make use of AllBright’s lists to conduct activism. Sooner Women recruit or later discriminatory fossils must die too. other women Amanda Lundeteg, CEO AllBright A record number of leaders are now preaching the importance of gender equality. But their words ring false. Nine out of ten companies are stuck and slow down the trend.