RADP Review Final Report: 19 December 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WELLFIELD ·I I

"~), ~ ',0 )/)'./ iiJ G./) / .,' it-3~" - - ' REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MATSHENG AREA GROUNDWATER INVESTIGATION (TB 10/2/12/92-93) DRAFT TECHNICAL REPORT T9: SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUGUST 1995 Prepared by = ~.-~~.. INTER WELLFIELD ·i i,.. CO'ISULT in association with BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Keyworth, Nottingham, UK MATSHENG AREA GROUNDWATER INVESTIGATION Technical Report T9 August 1995 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Usable potable water supplies are limited to the Matsheng village areas. Economic fresh water supplies identified during recent groundwater investigations are located in village areas of Lokgwabe and Lehututu. Brackish water supplies identified outside the village areas are not available for use by livestock using communal grazing areas as they are either in areas already occupied or in areas with other land use designations. 2. No significant usable water supplies were identified in the communal grazing areas through the MAGI programme, and based on the available geophysical evidence, the chances of striking groundwater supplies for livestock in Matsheng communal areas are poor. 3. Total water consumption in the Matsheng area during the past year (to May 1995) is estimated at 254,200m' (697 m' per day). Of this amount about 150,000 m' (60%) are consumed by livestock watered at about 150 wells, boreholes and dams on pans. 4. Matsheng village households using public standpipes consume about 670 litres per household per week, or 20 litres per person per day (67% of the 30 litre DWA standard rate for rural village standpipe users). Residents of the four RAD settlements served by council bowsers received a ration of about 7 litres per person per day, or just 23% of the DWA standard. -

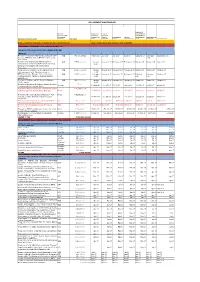

Submission Of

PROCUREMENT PLAN TEMPLATE Submission of Method of Submission of Issuing of Evaluation Reports Procurement (ICB, Documets to Invitation to to PPADB/MTC for NCB, selective, PPADB/MTC for Tender by Closing Date for Evaluation Adjudication and Award Decision by Description of Procurement activity QPP,Direct) Cost Estimate Vetting PPADB/MTC Tenders Completion by PE Award PPADB?MTC Contracts Signatire NAME OF MINISTRY: MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS NAME OF PERSONS(S) RESPONSIBLE FOR PROCUREMENT DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Category of Procurement (services/Supplies/Works) SERVICES Provision of Hardware Maintenance Services for IBM NCB P 6,070,179.26 March 2017 June 2017 July 2017 July 2017 August 2017 September September 2017 P-Series, IBM Blade Center, IBM 6400 printers and 2017 IBM Storage Provision of Unix/Linux and Windows System NCB P 5,500,000.00 January January 2017 February 2017 February 2017 March 2017 March 2017 May 2017 Administration Services for IBM P-Series and Linux 2017 Services in the Department of Information Technology Procurement of Hardware for the replacement of NCB P 12,000,000.00 January January 2017 February 2017 February 2017 March 2017 March 2017 March 2017 x86 environment with Migrations Services. 2017 IBM Tivoli Storage Manager Licenses Renewal NCB P 1,500,000.00 December January 2017 January 2017 February 2017 February February March 2017 (Licenses used for backup of business systems 2016 2017 2017 applications) Renewal of VMWare and Site Recovery Manager NCB P 5,000,000.00 January January 2017 February 2017 February 2017 March 2017 March 2017 March 2017 (SRM) Licenses 2017 Selectionof the Microsoft Software Advisor (Selection P 0.00 Selective 17/11/2016 01/01/2017 27/1/2017 02/10/2017 02/12/2017 16/2/2017 28/2/2017 of License Solution Provider (LSP)) Provision of Microsoft products - Desktop and Server P 45,699,130.69 (Enterprise Enrollment and Server & Cloud). -

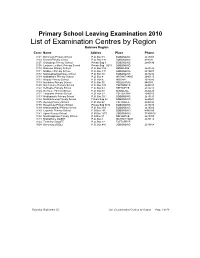

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

Local Communities, Cbos/Trusts, and People–Park Relationships: a Case Study of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana

Local Communities, CBOs/Trusts, and People–Park Relationships: A Case Study of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana Naomi Moswete and Brijesh Thapa Introduction The concept of community-based natural resources management (CBNRM) was introduced in Botswana in the early 1990s, and was premised on the idea that rural people must have the power to make decisions regarding utilization of natural resources (Mulale et al. 2013). CBNRM was built on the need for local participation and involvement in the management and utilization of protected areas, as well as community empowerment within and adjacent to them (Thakadu 2006; Mutandwa and Gadzirayi 2007). Based on these fundamental tenets, the CBNRM initiative was designed to alleviate poverty, advance conservation, strengthen rural economies, and empower communities to manage and derive equitable benefits from resources, as well as determine their long-term use (Arntzen et al. 2003; GoB 2007). Since its adoption, the implementation arm for CBNRM initiatives has been largely orchestrated through the formation and operation of a local community-based organization (CBO) and/or community trust (Moswete et al. 2009; Mbaiwa 2013). This local organizational entity (here- after referred to as a CBO/Trust) has evolved as an instrumental tool for rural communities as it provides a forum for them to negotiate their interests, problems, goals, and aspirations in a democratic and participatory process (Rozemeijer 2001; Arntzen et al. 2003; Mbaiwa 2013). This paper examines how local residents assess CBOs/Trusts, and people–park relation- ships, within the context of the Botswana portion of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (KTP). CBNRM in Botswana In Botswana, park-based tourism and/or community ecotourism is strongly linked to the notion of CBNRM (GoB 2007). -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

The Inconvenient Indigenous

1 SIDSEL SAUGESTAD The Inconvenient Indigenous Remote Area Development in Botswana, Donor Assistance, and the First People of the Kalahari The Nordic Africa Institute, 2001 2 The book is printed with support from the Norwegian Research Council. Front cover photo: Lokalane – one of the many small groups not recognised as a community in the official scheme of things Back cover photos from top: Irrigation – symbol of objectives and achievements of the RAD programme Children – always a hope for the future John Hardbattle – charismatic first leader of the First People of the Kalahari Ethno-tourism – old dance in new clothing Indexing terms Applied anthropology Bushmen Development programmes Ethnic relations Government policy Indigenous peoples Nation-building NORAD Botswana Kalahari San Photos: The author Language checking: Elaine Almén © The author and The Nordic Africa Institute 2001 ISBN 91-7106-475-3 Printed in Sweden by Centraltryckeriet Åke Svensson AB, Borås 2001 3 My home is in my heart it migrates with me What shall I say brother what shall I say sister They come and ask where is your home they come with papers and say this belongs to nobody this is government land everything belongs to the State What shall I say sister what shall I say brother […] All of this is my home and I carry it in my heart NILS ASLAK VALKEAPÄÄ Trekways of the Wind 1994 ∫ This conference that I see here is something very big. It can be the beginning of something big. I hope it is not the end of something big. ARON JOHANNES at the opening of the Regional San Conference in Gaborone, October 1993 4 Preface and Acknowledgements The title of this book is not a description of the indigenous people of Botswana, it is a characterisation of a prevailing attitude to this group. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Perceptions and Attitudes of Communities on Socio-Economic

Tselaesele et al. /Journal of Camelid Science 2021, 14 (1): 52-66 http://www.isocard.net/en/journal Perceptions and attitudes of communities on socio-economic importance of camels and consumption of camel milk and camel milk products in Kgalagadi District, Botswana Nelson Tselaesele1*, Eyassu Seifu2, Moenyane Molapisi2, Wame Boitumelo3, Ayana Angassa4, Keneilwe Kgosikoma5, Demel Teketay4, Bonno Sekwati-Monang2, Ezekiel Chimbombi6, Rosemary Kobue-Lekalake2, Geremew Bultosa2, Gulelat Desse Haki2, Witness Mojeremane5, Katsane Kgaudi7, Boitumelo Mokobi2 1Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, Botswana University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (BUAN); 2Department Food Science and Technology, BUAN; 3Department of Animal Science and Production, BUAN; 4Department of Range and Forest Resources, BUAN; 5Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, BUAN; 6Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering, BUAN; 7Tsabong Unified Secondary School. Abstract Camels were introduced to Botswana in the early twentieth century as a means of transport for the Botswana Police Service in the Kgalagadi District. This service was discontinued in the early 1980s and the camels were handed over to communities in the district for ecotourism activities. Since their introduction in Botswana, camels were regarded as government property and were never taken as alternative livelihood option that can alleviate poverty by providing milk and other products as is the case in other countries. This study explores the prospects of utilization of camel milk and milk products by assessing perceptions and attitudes of communities on the socio-economic importance of camels, consumption preferences for camel milk and value-added milk products. A combination of qualitative and quantitative methods was used to address the objectives of the research. -

EMERGENCY TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE to BOTSWANA for RURAL WATER SUPPLY T

WATER AND SANITATION KM» HEALTH PROJECT EMERGENCY TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE TO BOTSWANA Operated by FOR RURAL WATER SUPPLY CDM and Associates Sponsored by the U.S. Agency for International Development 1611 N. Kent Street, Room 1001 Arlington, VA 22209-2111 USA f c Telephone: (703) 243-8200 iNï:-:^AÏ!O !Ai: RF I-.[MINCE CENTRE Fax (703) 525-9137 FGFi1 CO;-".1'!.; • : i'V WAi'Lk' WUFPLY AND Telex WUI 64552 SANITATION IIACJ Cable Address WASHAID WASH FIELD REPORT NO. 269 « JULY 1989 • Prepared for the USAIU Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance and the USAID Mission in Botswana under WASH Activity No. 430 1 November 1993 TAS 472 M\)M Dear Colleague, On behalf of the WASH Project, I am pleased to provide you a copy of "Integrated Assessment of Hazardous Waste Management in Botswana," WASH Field Report No. 421, by Nancy Convard and Larry O'Toole. This report is based on a field visit to Botswana between June 11 and 28, 1993. It assesses hazardous waste management in Botswana, characterizes the country's policy and technical needs, and offers recommendations on establishing a hazardous waste management program. Please let me know if you require additional copies of this report or of related reports listed on the reverse of the title page. Comments or suggestions about this or any other WASH report are always welcome. Sincerely yours, Ç\ (^ ta - I] ^J. Ellis Turner WASH Project Director WASH Field Report No. 269 EMERGENCY TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE TO BOTSWANA FOR RURAL WATER SUPPLY t Prepared for the USAID Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance and the USAID Mission in Botswana under WASH Activity No. -

E-Government and Democracy in Botswana: Observational and Experimental Evidence on the Effects of E-Government Usage on Political Attitudes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bante, Jana et al. Working Paper E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Bante, Jana et al. (2021) : E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes, Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021, ISBN 978-3-96021-153-2, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp16.2021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

DAILY HANSARD 23 November 2020

DAILY YOUR VOICE IN PARLIAMENT THETHE SECOND FIRST MEETING MEETING OF THE O FSECOND THE FIFTH SESSION SESSION OF OF THETHE ELEVEN TWELFTHT HPARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT MONDAY 23 NOVEMBER 2020 MIXED VERSION HANSARDHANSARD NO: NO. 200 193 DISCLAIMER Unocial Hansard This transcript of Parliamentary proceedings is an unocial version of the Hansard and may contain inaccuracies. It is hereby published for general purposes only. The nal edited version of the Hansard will be published when available and can be obtained from the Assistant Clerk (Editorial). THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Phandu T. C. Skelemani PH, MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Mabuse M. Pule, MP. (Mochudi East) Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Mr L. T. Gaolaolwe Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Ms M. Mokgosi Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Dr M. E. K. Masisi, MP. - President His Honour S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti West) - Vice President Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Hon. K. N. S. Morwaeng, MP. (Molepolole South) - Administration Hon. K. T. Mmusi, MP. (Gabane-Mmankgodi) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. Dr L. Kwape, MP. (Kanye South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. E. M. Molale, MP. (Goodhope-Mabule ) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. K. S. Gare, MP. (Moshupa-Manyana) - Minister of Agricultural Development and Food Security Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation Hon. P. K. Kereng, MP. (Specially Elected) - and Tourism Hon. Dr E. G. Dikoloti MP. (Mmathethe-Molapowabojang) - Minister of Health and Wellness Hon. T.M. Segokgo, MP. (Tlokweng) - Minister of Transport and Communications Hon. -

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe