Political Power of Iranian Hierocracies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

2017 Raulvitorrodriguespeixoto.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS HUMANAS – DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA RAUL VITOR RODRIGUES PEIXOTO AS INTERAÇÕES DE UMA TRADIÇÃO APOCALÍPTICA NAS LITERATURAS ZOROASTRISTAS E JUDAICA: UM ESTUDO COMPARADO DA TEMÁTICA DO ORDÁLIO UNIVERSAL NA YASNA CAPÍTULO 51, GRANDE BUNDAHISHN CAPÍTULO 34 E LIVRO ETIÓPICO DE ENOCH CAPÍTULO 67 BRASÍLIA, 2017 1 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS HUMANAS – DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA RAUL VITOR RODRIGUES PEIXOTO AS INTERAÇÕES DE UMA TRADIÇÃO APOCALÍPTICA NAS LITERATURAS ZOROASTRISTAS E JUDAICA: UM ESTUDO COMPARADO DA TEMÁTICA DO ORDÁLIO UNIVERSAL NA YASNA CAPÍTULO 51, GRANDE BUNDAHISHN CAPÍTULO 34 E LIVRO ETIÓPICO DE ENOCH CAPÍTULO 67 Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em História, da Universidade de Brasília, como requisito obrigatório para obtenção do Título de Doutor em História (Área de Concentração: Sociedade, Cultura e Poder; Linha de Pesquisa: Política, Instituições e Relações de Poder). Orientador: Prof. Dr. Vicente Carlos Rodrigues Alvarez Dobroruka BRASÍLIA, 2017 2 Para Silvana, presente de Deus. 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Primeiramente agradeço a Deus, que tem me sustentado e se provado presente para comigo desde idos de 2012, quando comecei a envidar os esforços necessários para o processo seletivo de doutorado do final daquele ano. Agradeço ao Prof. Vicente Dobroruka, que tem sido orientador acadêmico e amigo. As disciplinas por ele ministradas no PPGHIS-UnB foram de fundamental importância para a minha formação como historiador. Agradeço também aos professores Farhad Sasani, Carmen Licia Palazzo, José Luiz Andrade Franco, Jane Adriana Ramos Ottoni de Castro e Celso Silva Fonseca que gentilmente aceitaram fazer parte desta banca examinadora. -

Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices

Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices General Editor: John R. Hinnells The University, Manchester In the series: The Sikhs W. Owen Cole and Piara Singh Sambhi Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices MaryBoyce ROUTLEDGE & KEGAN PAUL London, Boston and Henley HARVARD UNIVERSITY, UBRARY.: DEe 1 81979 First published in 1979 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd 39 Store Street, London WC1E 7DD, Broadway House, Newtown Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EN and 9 Park Street, Boston, Mass. 02108, USA Set in 10 on 12pt Garamond and printed in Great Britain by Lowe & BrydonePrinters Ltd Thetford, Norfolk © Mary Boyce 1979 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Boyce, Mary Zoroastrians. - (Libraryof religious beliefs and practices). I. Zoroastrianism - History I. Title II. Series ISBN 0 7100 0121 5 Dedicated in gratitude to the memory of HECTOR MUNRO CHADWICK Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the University of Cambridge 1912-4 1 Contents Preface XJ1l Glossary xv Signs and abbreviations XIX \/ I The background I Introduction I The Indo-Iranians 2 The old religion 3 cult The J The gods 6 the 12 Death and hereafter Conclusion 16 2 Zoroaster and his teaching 17 Introduction 17 Zoroaster and his mission 18 Ahura Mazda and his Adversary 19 The heptad and the seven creations 21 .. vu Contents Creation and the Three Times 25 Death and the hereafter 27 3 The establishing of Mazda -

A Brief Introduction to Zoroastrianism

A Brief Introduction to Zoroastrianism Zoroastrianism and Zarathustra Zoroastrianism has been called the “world’s oldest revealed religion.” The religion derives its title from the Iranian philosopher/poet/priest, Zarathustra, who is often referred to by the Greek version of his name - “Zoroaster.” The consensus both within the Zoroastrian community today (which numbers around 125,00-140,000 individuals around the world) and among Zoroastrian scholars is that Zarathustra lived sometime around 1250 BCE on the Central Asian Steppes, perhaps in what is now central Kazakhstan. Ancient Zoroastrianism is associated with the Iran. The name ‘Iran’ comes from an Old Iranian term Airyanem Vaejah – the ‘Aryan expanse’ or ‘the place where the Aryans lived.’ In Zoroastrian tradition, ‘Airyana Vaejah,’ comes to be regarded as the center of the world, a semi-mythical region where all great events of the past had taken place. Textual Sources Early Zoroastrianism is understood from the ‘writings’ and hymns of Zarathustra. The works reflect an Indo-Iranian cultural and linguistic background. The Indo- Iranians were tribes that shared a common religious culture and drifted apart during the late 3rd /early 2nd millennium BCE, with the Iranians moving towards the Iranian plateau, arriving there early in the 1st millennium BCE, and the Indo- Aryans settling in the Indian subcontinent around 1500 BCE. The earliest Zoroastrian texts, the Gāthās – “songs” or “hymns” - were composed in Old Avestan, an Old Iranian language close in language and style to the Sanskrit of the Rig Veda. The Gāthās and later Zoroastrian scriptures (in Young Avestan) seem to be geographically localized in north-eastern/eastern Iran. -

Ameretat-Hebrew.Pdf

Ameretat Ameretat (Amərətāt) is the Avestan language name of Avestan texts allude to their respective guardianships of the Zoroastrian divinity/divine concept of immortality. plant life and water (comparable with the Gathic allusion Ameretat is the Amesha Spenta of long life on earth and to sustenence), but these identifications are only properly perpetuality in the hereafter. developed in later tradition (see below). These associa- The word amərətāt is grammatically feminine and the tions with also reflect the Zoroastrian cosmological model divinity Ameretat is a female entity. Etymologically, in which each of the Amesha Spentas is identified with Avestan amərətāt derives from an Indo-Iranian root and one aspect of creation. is linguistically related to Vedic Sanskrit amṛtatva. In The antithetical counterpart of Ameretat is the demon Sassanid Era Zoroastrian tradition, Ameretat appears as (daeva) Shud “hunger”, while Haurvatat’s counterpart is Middle Persian Amurdad, continuing in New Persian as Tarshna “thirst”. Ameretat and Haurvatat are the only Mordad or Amordad. two Amesha Spentas who are not already assigned an an- tithetical counterpart in the Gathas. In the eschatological framework of Yasht 1.25, Ameretat and Haurvatat repre- 1 In scripture sent the reward of the righteous after death (cf. Ashi and ashavan). 1.1 In the Gathas 2 In tradition Like the other Amesha Spentas also, Ameretat is already attested in the Gathas, the oldest texts of the Zoroastrian- ism and considered to have been composed by Zoroaster In the Bundahishn, a Zoroastrian account of creation himself. And like most other principles, Ameretat is not completed in the 12th century, Ameretat and Haurvatat unambiguously an entity in those hymns. -

Mazdaism. the Religion of the Ancient Persians. Illustrated

MAZDAISM. BY THE EDITOR. MAZDAISM, the belief of the ancient Persians, is perhaps the most remarkable religion of antiquity, not only on account of the purity of its ethics, but also by reason of the striking similar- ities which it bears to Christianity. Ahura Mazda, the Lord Omniscient, is frequently represented (as seen in Fig. i) upon bas-reliefs of Persian monuments and rock Fig. I. Ahurx Mazda. (Conventional reproduction of the figure on the great rock inscription of Darius at Behistan.) inscriptions. He reveals himself through "the excellent, the pure and stirring Word," also called "the creative Word which was in the beginning," which reminds one not only of the Christian idea of the Logos, 6 Xoyos o? r)v iv oepx^, but also of the Brah- man Fdc/i, word (etymologically the same as the Latin vox), which is glorified in the fourth hymn of the Rig Veda, as "pervading heaven and earth, existing in all the worlds and extending to the heavens." 142 THE OPEN COURT. On the rock inscription of Elvend, which had been made by the order of King Darius, we read these Hnes^: " There is one God, omnipotent Ahura Mazda, It is who has created the earth here He ; It is has created the heaven there He who ; It is He who has created mortal man." Lenormant characterises the God of Zoroaster as follows : "Ahura Mazda has creaited as/ia, purity or rather the cosmic order; he has created both the moral and material world constitution ; he has made the universe; [datar], [ahura), he has made the law ; he is, in a word, creator sovereign omnis- Fig. -

Parsi) Hill - Jimmy Suratia 28 Finding ‘Saosha, Tying Kusti’ in Sogdiana

Become a member online with a simple click or through the following individuals: UK residents and other countries please send completed application form and cheque payable in Sterling to WZO, London to: Mrs Khurshid Kapadia, 217 Pickhurst Rise, West Wickham, Kent BR4 0AQ, UK. USA residents - application form and cheque payable in US Dollars as “The World Zoroastrian Organisation (US Region)” to: Mr Kayomarsh Mehta, 6943 Fieldstone Drive, Burr Ridge, Illinois IL60527-5295, USA. Canadian residents - application form and cheque payable in Canadian Dollars as “ZSO” and marked WZO fees to: The Treasurer, ZSO, 3590 Bayview Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M2M 356, Canada. Ph: (416) 733 4586. New Zealand residents - application form with your cheque payable in NZ Dollars as “World Zoroastrian Organisation, to: Mr Darius Mistry, 134A Paritai Drive, Orakei, Auckland, New Zealand HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2014 COVER The four images used are on pages 71 & 72 where full credit is given. PHOTOGRAPHS Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in C o n t e n t s the magazine or as mentioned. 04 Abtin Sassanfar WZO WEBSITE 05 Report from the Chairman, WZO 07 European Interfaith Youth Network - benafsha engineer www.w-z-o.org 10 “Marriage nu spot Fixing” - pauruchisty kadodwala 11 Be Good - Sing Ashem Vohu - khosro mehrfar 13 Structural Limits on Gatha Studies - dinyar mistry 16 A Gathic View of Zoroastrianism & Ethical Life - review, soli dastur 19 Farohar/Fravahar Motif. Parts I & II - k.e.eduljee 25 Commemoration of the Zoroastrian (Parsi) Hill - jimmy suratia 28 Finding ‘Saosha, tying Kusti’ in Sogdiana. Part I - kersi shroff 32 The Cyrus Cylinder at the MET - behroze clubwalla 36 The Cyrus Cylinder’s visit to SF - nazneen spliedt 38 Four Funerals & a Concert for ‘Peace’ - dilnaz boga 40 Dr Murad Lala scales Mt Everest - beyniaz edulji 44 Outstanding Young Houstonian - magdalena rustomji 46 The Jam e Janbakhtegan Games - taj gohar kuchaki 48 G.K. -

Spring 2014-Ver04.Indd

ZOROASTRIAN SPORTS COMMITTEE With Best Compliments is pleased to announce from ththth The Incorporated Trustees The 14 Z Games of the July 2-6, 2014 Zoroastrian Charity Funds of Cal State Dominguez Hills Los Angeles, CA, USA Hongkong, Canton & Macao ONLINE REGISTRATION NOW OPEN! www.ZATHLETICS.com www.zathletics.com | [email protected] FOR UP TO THE MINUTE DETAILS, FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA @ZSports @ZSports ZSC FEZANA JOURNAL PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 1 March / Spring 2014, Bahar 1383 AY 3752 Z 2224 36 60 02 Editorials 83 Behind the Scenes 122 Matrimonials 07 FEZANA Updates Firoza Punthakey-Mistree and 123 Obituary Pheroza Godrej 13 FEZANA Scholarships 126 Between the Covers Maneck Davar 41 Congress Follow UP FEZANA JOURNAL Ashishwang Irani Darius J Khambata welcomes related stories 95 In the News from all over the world. Be Khojeste Mistree a volunteer correspondent 105 Culture and History Dastur Peshotan Mirza or reporter 114 Interfaith & Interalia Dastur Khurshed Dastoor CONTACT 118 Personal Profile Issues of Fertility editor(@)fezana.org 119 Milestones Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, lmalphonse(@)gmail.com Language Editor: Douglas Lange Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, ffitch(@)lexicongraphics.com Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia bpastakia(@)aol.com Cover design Columnists: Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi: rabadis(@)gmail.com; Feroza Fitch -

Zoroaster : the Prophet of Ancient Iran

BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF 1891 AJUUh : :::^.l.ipq.'f.. "Jniversity Library DL131 1o5b.J13Hcirir'^PItl®" ^°'°nnmliA ,SI'.?.P!}SL°LmmX Jran / 3 1924 022 982 502 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022982502 ZOROASTER THE PROPHET OF ANCIENT IRAN •The; •S- ZOROASTER THE PROPHET OF ANCIENT HIAN BY A. V. WILLIAMS JACKSON PROFESSOK OF INDO-IBANIAN LANGUAGES IN COLUMBIA UNIVKRSITT KTefa gorft PUBLISHED FOE THE COLUMBIA UNIVEESITT PRESS BY THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd. 1899 All rights reserved Copyright, 1898, bt the macmillan company. J. S. Gushing k Co. — Berwick & Smith Norwood Mass. U.S.A. DR. E. W. WEST AS A MARK OF REGARD PREFACE This work deals with the life and legend of Zoroaster, the Prophet of Ancient Iran, the representative and type of the laws of the Medes and Persians, the Master whose teaching the Parsis to-day still faithfully follow. It is a biographical study based on tradition ; tradition is a phase of history, and it is the purpose of the volume to present the picture of Zoroaster as far as possible in its historic light. The suggestion which first inspired me to deal with this special theme came from my friend and teacher. Professor Geldner of Berlin, at the time when I was a student under him, ten years ago, at the University of Halle in Germany, and when he was lecturing for the term upon the life and teachings of Zoroaster. -

Farohar the Spirit of the Matter

Farohar The spirit of the matter Talking about Farohars, here's a nice article on it which appeared in the Times of India last year. Regards Nauzer K. Bharucha ------------ --------- --------- --------- --------- --------- -------- The spirit of the matter Adi F. Doctor on Farohar, the religious symbol of the Zoroastrians FROM the astodan (receptacle for bones) of King Darius the Great at Naqsh-e-Rustam in Iran nearly 2,500 years ago and the door- post of palaces of other Achaemenian kings, to the portals and acades of present-day fire temples of the Parsis and the fair neck of a modern Parsi girl, not to mention stickers on cars, the one common symbol that adorns them is the winged human figure. Different interpretations of this figure have been given by historians and scholars, ranging from Ahura Mazda (supreme creator), Farohar and the Kyanian Glory. Even today, Parsis of India call it Farohar, the most sublime guardian spirit of every human soul. But that is not correct; for if we cannot visualise the soul how can its guardian spirit be imagined? Besides, the original detailed version of this winged figure is to be found on the astodan of King Darius I, which shows the exalted king who was a `Dahyupata' (righteous ruler-cf.sansk. `dharmaraja' ), praying before the fire altar. A winged human figure is seen in the air between the King and the fire. The mystery of this figure was solved by the hermeneutist par excellence of Zoroastrian scriptures, the late Dr Framroze S. Chiniwala in the early thirties of this century. In the detailed `ta'vil' or exegesis of this bas relief at Naqsh-e-Rustam, he has explained that the winged figure is the expanded astral or subtle form (Kherpa) of the King, embodying his exalted thoughts almost all the ancient Iranian monarchs and paladins were highly advanced souls. -

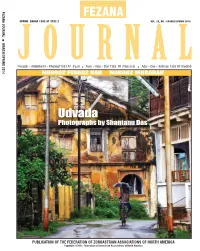

Fezana Journal

FEZANA JOURNAL PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 30 No 1 Spring / Bahar 1385 AY 3754 Z 9 25 39 44 02 Editorial Dolly Dastoor 50 Appeal from Funds and 106 Inauguration of Arbab Finance Committee Rustom Guiv Dar e Mehr, 03 Message from the New York President 51 6th World Zoroastrian Youth Congress,- New 109 Personal Profiles 05 FEZANA Update Zealand 112 Interfaith /Interalia 09 COVER STORY 59 FEZANA Scholarships Kurds and their 113 Milestones Zoroastrian Roots 80 Chothia Scholarships 44 Connection between 114 Matrimonials Judiasm and 81 Vakhshoori Schoalrships Zoroastrianism 115 Obituary 85 Zoroastrian Young Adults 49 OZCF plans to build well being 121 Books and Arts consecrated Atashkadeh (Agiary) with Atash 88 IN THE NEWS Adaran Fire Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, lmalphonse(@)gmail.com Language Editor: Douglas Lange Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, ffitch(@)lexicongraphics.com Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia bpastakia(@)aol.com Columnists: Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi: rabadis(@)gmail.com; Teenaz Javat: teenazjavat(@)hotmail.com; Mahrukh Motafram: mahrukhm83(@)gmail.com Copy editors: Vahishta Canteenwalla, Yasmin Pavri, Nazneen Khumbatta Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: ahsethna(@)yahoo.com; Kershaw Cover design Feroza Fitch of Lexicongraphics Khumbatta: Arnavaz Sethna(@)yahoo.com Photo copyright Shirin Kumana Wadia Summer 2016 Fravadin – Ardibehesht – Khordad 1385 AY (Fasli) THE FESTIVAL OF MEHREGAN Avan - Adar – Dae 1385 AY (Shenshai) GUEST EDITOR Adar- Dae- Behman 1385 AY (Kadimi) FARIBORZ RAHNAMOON Opinions expressed in the FEZANA Journal do not necessarily reflect the views of FEZANA or members of the editorial board.