The Getty Bronze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archimedes' Lever and Vesuvius Eruption A.D. 79

Journal Of Anthropological And Archaeological Sciences DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2020.01.000119 ISSN: 2690-5752 Research Article The Archimedes’ Lever and Vesuvius Eruption A.D. 79 Alexander N Safronov* AM Obukhov Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia *Corresponding author: Alexander N Safronov, AM Obukhov Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Pyzhevskii, Moscow, Russia Received: February 07, 2020 Published: February 24, 2020 Abstract The study based on detailed analysis of the Villa of the Mysteries frescoes, which were discovered early at the excavations in Pompeii. It was shown that the Villa of the Mysteries is a school of priestesses-seismologists. It is established that the frescoes depict the process of priestesses introducing in the Hera seismoacoustic cult (Zeus-Hera-Dionysus cult). It is shown that in the Hera cult the wand strike on the back of the graduate priest student symbolizes the fact of the introduction of the priestesses to the priesthood. The comparison between Pythagoras School in Crotone, Southern Italy (Temple of the Muse) and Cumaean Sibyl seismoacoustic at margin of Campi Flegrei, Gulf of Naples and school at Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii was carried out. Some caustic remarks about interpretation of Homer and Lion Hunting were written. It is shown that Archimedes’ lever principal is theoretical basis of the Roman Empire volcanology and seismology. The Archimedes’ lever principal of planet alignment was demonstrated in several examples of the large up-to-date explosive eruptions with Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) greater than 4+ (6 examples). It was noted that the Pythagoras-Plato gravitational waves (vortexes) were known in Europe since Thales of Miletus and Pythagoras. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Articulation and the Origins of Proportion in Archaic and Classical Greece

Articulation and the origins of proportion in archaic and classical Greece Lian Chang School of Architecture McGill University, Montreal, Canada August 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Lian Chang 2009 Abstract This dissertation searches for the origins of western ideas of proportion in the archaic and classical Greek conceptual terrain of articulation. We think of articulation, in the first instance, as having to do with the joining of parts to fabricate an object, such as in the physical connection of pieces of wood, cloth, metal, or stone. However, the early Greek language that described these craft processes also, and inextricably, spoke in a number of ways about what it meant for a person, thing, or the world to be beautiful, healthy, and just. Taking Homer as its primary source, Part One therefore explores archaic ideas of bodily experience (Chapter One); of crafts (Chapter Two); and of the interrelations between the two (Chapter Three). These chapters lay emphasis on how the language and concepts of articulation constructed a worldview particular to early Greece. Part Two then examines early ideas of proportion, in social and political life as depicted by Homer (Chapter Four); in classical ideas about the medicalized human body and the civic body of the polis (Chapter Five); and in the cosmogonic theories of Empedocles and Plato (Chapter Six). In so doing, I aim to demonstrate how ideas of articulation allowed for and expanded into those of proportion, binding together the ordering of bodies, of the kosmos, and of crafts, including architecture. -

PL. LXI.J the Position of Polykleitos in the History of Greek

A TERRA-COTTA DIADUMENOS. 243 A TERRA-COTTA DIADUMENOS. [PL. LXI.J THE position of Polykleitos in the history of Greek sculpture is peculiarly tantalizing. We seem to know a good deal about his work. We know his statue of a Doryphoros from the marble copy of it in Naples, and we know his Diadumenos from two marble copies in the British Museum. Yet with these and other sources of knowledge, it happens that when we desire to get closer to his real style and to define it there occurs a void. So to speak, a bridge is wanting at the end of an otherwise agreeable journey, and we welcome the best help that comes to hand. There is, I think, some such help to be obtained from the terra-cotta statuette recently acquired in Smyrna by Mr. W. R. Paton. But first it may be of use to recall the reasons why the marble statues just mentioned must fail to convey a perfectly true notion of originals which we are justified in assuming were of bronze. In each of these statues the artist has been compelled by the nature of the material to introduce a massive support in the shape of a tree stem. That is at once a new element in the design, and, as a distinguished French sculptor1 has rightly observed, this new element called for a modification of the entire figure. This would have been true of a marble copy made even 1 M. Eugene Guillaume, in Eayet's dell' Tnst. Arch, 1878, p. 5. He gives Monuments de VArt Antique, pt. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

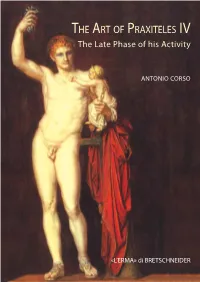

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

A Masterpiece of Ancient Greece

Press Release A Masterpiece of Ancient Multimedia Greece: a World of Men, Feb. 01 - Sept. 01 2013 Gods, and Heroes DNP, Gotanda Building, Tokyo Louvre - DNP Museum Lab Tenth presentation in Tokyo The tenth Louvre - DNP Museum Lab presentation, which closes the second phase of this partnership between the Louvre and Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd (DNP), invites visitors to discover the art of ancient Greece, a civilization which had a significant impact on Western art and culture. They will be able to admire four works from the Louvre's Greek art collection, and in particular a ceramic masterpiece known as the Krater of Antaeus. This experimental exhibition features a series of original multimedia displays designed to enhance the observation and understanding of Greek artworks. Three of the displays designed for this presentation are scheduled for relocation in 2014 to the Louvre in Paris. They will be installed in three rooms of the Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Red-figure calyx krater Signed by the painter Euphronios, attributed to the Antiquities, one of which is currently home to the Venus de Milo. potter Euxitheos. Athens, c. 515–510 BC. Clay The first two phases of this project, conducted over a seven-year Paris, Musée du Louvre. G 103 period, have allowed the Louvre and DNP to explore new © Photo DNP / Philippe Fuzeau approaches to art using digital and imaging technologies; the results have convinced them of the interest of this joint venture, which they now intend to pursue along different lines. Location : Louvre – DNP Museum Lab Ground Floor, DNP - Gotanda 3-5-20 Nishi-Gotanda, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo The "Krater of Antaeus", one of the Louvre's must-see masterpieces, Opening period : provides a perfect illustration of the beauty and quality of Greek Friday February 1 to Sunday September 1, ceramics. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

E. General Subjects

Index E. General Subjects Academia (of Cicero) 13, 97 books-papyrus rolls-codices 22, 54–56, 65–71, 158–160 Adonis (image of) 48 booty, see plunder Aedes Concordiae, see Index B: Roma Boxers (sculptural group) 72 Akademia, see Index B: Athenai Bronze Age 21 Akropolis, see Index B: Athenai bronze from Korinthos 11, 12, 92 Alexandros the Great (dedications by) 28 bronze horses (statues of) 74 Alexandros the Great (portraits of) 47, 52, 94 bronze sculpture (large) 4, 14, 33, 43, 44, 46, 49, 51, 52, 72, 74, 82, 92, Alexandros the Great (spoliation by) 39, 41, 43, 47 122, 123, 130, 131–132, 134–135, 140, 144, 149, 151, 159, 160 Alexandros the Great’s table 2, 106 bronze sculpture (small) 14, 46, 53, 92, 106, 123, 138, 157 Alkaios (portrait of) 53 bronze tablets 81 altar 2, 42 Altar of Zeus, see Index B: Pergamon, Great Altar cameos 55–70 amazon 14, 134 Campus Martius, see Index B: Roma ancestralism 157, 159 canon 156, 159, 160–162 Antigonid Dynasty 46, 49 canopus 133 antiquarianism 4, 22, 25, 28, 31, 44, 55, 65–66, 73, 80, 81, 82, 156–157, Capitoline Hill, see Index B: Roma, Mons Capitolinus 159–160, 161 Capitolium, see Index B: Roma Anubis (statue of) 75 Carthaginians 9, 34, 104 Aphrodite, see Index C: Aphrodite catalogue, see also inventory, 93 Aphrodite (statue of) 52 censor, see Index D: censor Aphrodite of Knidos (statue of), see Index C: Praxiteles centaur, see Index D: kentauroi Apollon (statue of) 49, 72 Ceres (statue of) 72 Apollonios (portrait of) 53 chasing (chased silver) 104 Apoxyomenos (statue of), see Index C: Lysippos citronwood -

THE APOXYOMENOS of LYSIPPUS. in the Hellenic Journal for 1903

THE APOXYOMENOS OF LYSIPPUS. IN the Hellenic Journal for 1903, while publishing some heads of Apollo, I took occasion to express my doubts as to the expediency of hereafter taking the Apoxyomenos as the norm of the works of Lysippus. These views, how- ever, were not expressed in any detail, and occurring at the end of a paper devoted to other matters, have not attracted much attention from archaeolo- gists. The subject is of great importance, since if my contention be justified, much of the history of Greek sculpture in the fourth century will have to be reconsidered. Being still convinced of the justice of the view which I took two years ago, I feel bound to bring it forward in more detail and with a fuller statement of reasons. Our knowledge of many of the sculptors of the fourth century, Praxiteles, Scopas, Bryaxis, Timotheus, and others, has been enormously enlarged during the last thirty years through our discovery of works proved by documentary evidence to have been either actually executed by them, or at least made under their direction. But in the case of Lysippus no such discovery was made until the very important identification of the Agias at Delphi as a copy of a statue by this master. Hitherto we had been content to take the Apoxyomenos as the best indication of Lysippic style ; and apparently few archaeologists realized how slender was the evidence on which its assignment to Lysippus was based. That assignment took place many years ago, when archaeological method was lax ; and it has not been subjected to sufficiently searching criticism. -

Focus on Greek Sculpture

Focus on Greek Sculpture Notes for teachers Greek sculpture at the Ashmolean • The classical world was full of large high quality statues of bronze and marble that honoured gods, heroes, rulers, military leaders and ordinary people. The Ashmolean’s cast collection, one of the best- preserved collections of casts of Greek and Roman sculpture in the UK, contains some 900 plaster casts of statues, reliefs and architectural sculptures. It is particularly strong in classical sculpture but also includes important Hellenistic and Roman material. Cast collections provided exemplary models for students in art academies to learn to draw and were used for teaching classical archaeology. • Many of the historical casts, some dating back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, are in better condition than the acid rain-damaged originals from which they were moulded. They are exact plaster replicas made, with piece moulds that leave distinctive seams on the surface of the cast. • The thematic arrangement of the Cast Gallery presents the contexts in which statues were used in antiquity; sanctuaries, tombs and public spaces. Other galleries containing Greek sculpture, casts and ancient Greek objects Gallery 14: Cast Gallery Gallery 21: Greek and Roman Sculpture Gallery 16: The Greek World Gallery 7: Money Gallery 2: Crossing Cultures Gallery 14: Cast Gallery 1. Cast of early Greek kouros, Delphi, Greece, 2. Cast of ‘Peplos kore’, from Athenian Acropolis, c570BC c530BC The stocky, heavily muscled naked figure stands The young woman held an offering in her in the schematic ‘walking’ pose copied from outstretched left hand (missing) and wears an Egypt by early Greek sculptors, signifying motion unusual combination of clothes: a thin under- and life. -

Chapter 5 Th a F a I G E Art of Ancient Greece (Iron Age)

Chapter 5 The Art of A nci ent G reece (Iron Age) Famous Greeks: Playwriters: Aeschylus (“father of Greek tragedy”), Sophocles (Antigone, Oedipus), Euripides, Aristophanes (Comedies. Lysistrata) Philosophers: Heraclitus (“You can never step into the same river twice”) Plato,,, Socrates, Aristotles Mathematicians and scientists: Archimedes, Pythagoras, Aristotles, Euclid Authors and poets: Homer (Odyssey and Iliad), Sappho of Lesbos, Aesop Historians: Herodotus ("The Father of History,"). Thucydides The Greek World GtiPid(9Geometric Period (9-8th c. BCE) Early Geometric Krater. C. 800 BCE Krater A bowl for mixing wine and water Greek key or Meander An ornament consisting of interlocking geometric motifs. An ornamental pattern of contiguous straight lines joined usually at right angles. Geometric krater, from the Dipylon cemetery, Athens, Greece, ca. 740 BCE. Approx. 3’ 4 1/2” high. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Geometric krater, from the Dipylon cemetery. Detail. Hero and Centaur (Herakles and Nessos? Achilles and Chiron?) ca. 750–730 BCE. Bron ze, a pprox. 4 1/2” high. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Geometric krater, from the Dipylon cemetery, Athens, Greece, ca. 740 BCE. Approx. 3’ 4 1/2” high. Hero and Centaur (Herakles and Nessos? Achilles and Chiron?) ca. 750–730 BCE. Bronze, approx. 4 1/2” high. Greek Vase Painting Orientalizing Period (7th c. BCE) Pitcher (olpe) Corinth, c. 600 BCE Ceramic with black-figure decoration, height 11½ " British Mus . London Rosette: A round or oval ornament resembling a rose Comppyarison: Assyrian.. Lamassu, ca. 720–705 BCE. Pitcher (olpe) Corinth, c. 600 BCE Ceramic with black-figure decoration, height 11½" British Mus. -

Apoxyomenos: Discovery, Underwater Excavation, and Survey Jasen Mesić, MP, Parliament of Croatia, Committee for Science, Education, and Culture

Program as of September 29, 2015; subject to change Tuesday, October 13 --The Getty Center 9:45 a.m. Check-in opens Museum Lecture Hall lobby Viewing of Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World Exhibition Pavilion (opens 10:00 a.m.) Lunch on your own 12:30 p.m. Welcome and Introduction – Museum Lecture Hall Timothy Potts, J. Paul Getty Museum Kenneth Lapatin, J. Paul Getty Museum 1:00 p.m. Session I: Apoxyomenoi and Large-Scale Bronzes I – Museum Lecture Hall Chair: Jens Daehner, J. Paul Getty Museum The Bronze Athlete from Ephesos: Archaeological Background and History of its Classification Georg Plattner and Kurt Gschwantler, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna The Bronze Athlete from Ephesos: Restauration History and Stability Evaluation Bettina Vak, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna Apoxyomenos: Discovery, Underwater Excavation, and Survey Jasen Mesić, MP, Parliament of Croatia, Committee for Science, Education, and Culture New Results on the Alloys of the Croatian Apoxyomenos Iskra Karniš Vidovi , Croatian Conservation Institute, Zagreb The Use of Inlays inč Early Greek Bronzes Seán Hemingway and Dorothy H. Abramitis, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Was the Colossus of Rhodes Cast in Courses or in Large Sections? Ursula Vedder, Kommission für Alte Geschichte und Epigraphik des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Munich Break; refreshments served © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust 19th International Congress on Ancient Bronzes, Oct. 13-17, 2015 Program as of September 29, 2015 Page 1 of 12 Program as of September 29, 2015; subject to change Tuesday, October 13 --The Getty Center (con’t) 3:30 p.m. Session II: Large-Scale Bronzes II – Museum Lecture Hall Chair: Sophie Descamps, Musée du Louvre, Paris A Royal Macedonian Portrait Head from the Sea off Kalymnos Olga Palagia, University of Athens The Bronze Head of Arsinoe III in Mantua and the Typology of Ptolemaic Divinization of the Archelaos Relief Patricia A.