Masaryk University in Brno

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papeete, Tahiti

Global Aviation M A G A Z I N E Issue 69/ May 2016 Page 1 - Introduction Welcome on board this Global Aircraft. In this issue of the Global Aviation Magazine, we will take a look at two more Global Lines cities Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada and Papeete, Tahiti. We also take another look at a featured aircraft in the Global Fleet. This month’s featured aircraft is the Embraer ERJ-145. We wish you a pleasant flight. 2. Vancouver, B.C., Canada – West Meets Best 4. Papeete, Tahiti – Pacific Paradise 6. Pilot Information 8. Introducing the Embraer ERJ-145LR – With All the Frills 10. In-flight Movies/Featured Music Page 2 – Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada – West Meets Best Vancouver is a coastal city located in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, Canada. It is named for British Captain George Vancouver, who explored and first mapped the area in the 1790s. The metropolitan area is the most populous in Western Canada and the third-largest in the country, with the city proper ranked eighth among Canadian cities. According to the 2006 census Vancouver had a population of 578,041 and just over 2.1 million people resided in its metropolitan area. Over the last 30 years, immigration has dramatically increased, making the city more ethnically and linguistically diverse; 52% do not speak English as their first language. Almost 30% of the city's inhabitants are of Chinese heritage. From a logging sawmill established in 1867 a settlement named Gastown grew, around which a town site named Granville arose. With the announcement that the railhead would reach the site, it was renamed "Vancouver" and incorporated as a city in 1886. -

Shotgun Team Takes Home the Gold

Michigan’s oldest college newspaper Vol. 137, Issue 24 - 17 April 2014 www.hillsdalecollegian.com Senior class officers elected Micah Meadowcroft Assistant Editor Junior Andy Reuss was named president of the class of 2015 Wednesday. “I’m really excited to have the opportunity to serve my se- nior class,” Reuss said. “I’m honored that my classmates have entrusted me with this responsi- bility, and I’m excited about who I get to work with and make our senior year one for the books.” PRESIDENT Rising seniors voted Tuesday ANDY REUSS and Wednesday. Reuss is joined on next year’s senior committee by juniors Heather Lantis as vice president, Kadeem Norray as treasurer, Annie Teigan as secre- tary, and Shelly Peters as social chair. The committee is responsible for the planning and execution of all senior class events, including the senior party, the senior gift, and future class reunions. Joanna Wiseley, director of career services, said there was great voter turnout, with over VICE PRESIDENT 200 juniors casting a ballot. The Hillsdale College shotgun team took home gold in the Division III ACUI championship, winning in sporting clays “I look forward to the oppor- and five-stand. The team hit 550 out of 600 possible targets. (Courtesy of Jordan Hintz) HEATHER LANTIS tunity to work with them next year,” she said. Besides class president, Re- uss is an English and politics Shotgun team takes home the gold double major, and will be head resident assistant in the Simpson Jack Butler Hillsdale’s size, with programs more targets than the second performance as you can get,” Carl Residence next year. -

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

Lista MP3 Por Genero

Rock & Roll 1955 - 1956 14668 17 - Bill Justis - Raunchy (Album: 247 en el CD: MP3Albms020 ) (Album: 793 en el CD: MP3Albms074 ) 14669 18 - Eddie Cochran - Summertime Blues 14670 19 - Danny and the Juniors - At The Hop 2561 01 - Bony moronie (Popotitos) - Williams 11641 01 - Rock Around the Clock - Bill Haley an 14671 20 - Larry Williams - Bony Moronie 2562 02 - Around the clock (alrededor del reloj) - 11642 02 - Long Tall Sally - Little Richard 14672 21 - Marty Wilde - Endless Sleep 2563 03 - Good golly miss molly (La plaga) - Bla 11643 03 - Blue Suede Shoes - Carl Perkins 14673 22 - Pat Boone - A Wonderful Time Up Th 2564 04 - Lucile - R Penniman-A collins 11644 04 - Ain't that a Shame - Pat Boone 14674 23 - The Champs - Tequila 2565 05 - All shock up (Estremecete) - Blockwell 11645 05 - The Great Pretender - The Platters 14675 24 - The Teddy Bears - To Know Him Is To 2566 06 - Rockin' little angel (Rock del angelito) 11646 06 - Shake, Rattle and Roll - Bill Haley and 2567 07 - School confidential (Confid de secund 11647 07 - Be Bop A Lula - Gene Vincent 1959 2568 08 - Wake up little susie (Levantate susani 11648 08 - Only You - The Platters (Album: 1006 en el CD: MP3Albms094 ) 2569 09 - Don't be cruel (No seas cruel) - Black 11649 09 - The Saints Rock 'n' Roll - Bill Haley an 14676 01 - Lipstick on your collar - Connie Franci 2570 10 - Red river rock (Rock del rio rojo) - Kin 11650 10 - Rock with the Caveman - Tommy Ste 14677 02 - What do you want - Adam Faith 2571 11 - C' mon everydody (Avientense todos) 11651 11 - Tweedle Dee - Georgia Gibbs 14678 03 - Oh Carol - Neil Sedaka 2572 12 - Tutti frutti - La bastrie-Penniman-Lubin 11652 12 - I'll be Home - Pat Boone 14679 04 - Venus - Frankie Avalon 2573 13 - What'd I say (Que voy a hacer) - R. -

Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles' Films

“All I’ve got to do is Act Naturally”: Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles’ Films Submitted by Stephanie Anne Piotrowski, AHEA, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English (Film Studies), 01 October 2008. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which in not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (signed)…………Stephanie Piotrowski ……………… Piotrowski 2 Abstract In this thesis, I examine the Beatles’ five feature films in order to argue how undermining generic convention and manipulating performance codes allowed the band to control their relationship with their audience and to gain autonomy over their output. Drawing from P. David Marshall’s work on defining performance codes from the music, film, and television industries, I examine film form and style to illustrate how the Beatles’ filmmakers used these codes in different combinations from previous pop and classical musicals in order to illicit certain responses from the audience. In doing so, the role of the audience from passive viewer to active participant changed the way musicians used film to communicate with their fans. I also consider how the Beatles’ image changed throughout their career as reflected in their films as a way of charting the band’s journey from pop stars to musicians, while also considering the social and cultural factors represented in the band’s image. -

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

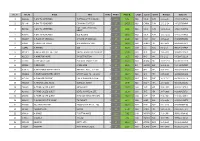

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Jazz – Pop – Rock Gesamtliste Stand Januar 2021

Jazz – Pop – Rock Gesamtliste Stand Januar 2021 50 Cent Thing is back CD 1441 77 Bombay Str. Up in the Sky CD 1332 77 Bombay Street Oko Town CD 1442 77 Bombay Street Seven Mountains CD 1684 7 Dollar Taxi Bomb Shelter Romance CD 1903 Abba The Definitive Collection CD 1085 Abba Gold CD 243 Abba (Feat.) Mamma Mia! Feat. Abba CD 992 Above & Beyond We are all we need CD 1643 AC/DC Black Ice CD 1044 AC/DC Rock or Bust CD 1627 Adams, Bryan Tracks of my Years CD 1611 Adams, Bryan Reckless CD 1689 Adele Adele 19 CD 1009 Adele Adele: 21 CD 1285 Adele Adele 25 CD 1703 Aguilera, Christina Liberation CD 1831 a-ha 25 Twenty Five CD 1239 Airbow, Tenzin Reflecting Signs CD 1924 Albin Brun/Patricia Draeger Glisch d’atun CD 1849 Ali Erol CD 1801 Allen, Lily It’s not Me, it’s You CD 1550 Allen, Lily Sheezus CD 1574 Alt-J An Awsome Wave CD 1503 Alt-J This is all yours CD 1637 Alt-J This is all yours, too CD 1654 Amir Au Cœurs de moi CD 1730 Girac, Kendji Amigo CD 1842 Anastacia Heavy rotation CD 1301 Anastacia Resurrection CD 1587 Angèle Brol la Suite CD 1916 Anthony, Marc El Cantante CD 1676 Arctic Monkeys Whatever people say CD 1617 Armatrading, Joan Starlight CD 1423 Ärzte, Die Jazz ist anders CD 911 Aslan Hype CD 1818 Avicii Tim CD 1892 Avidan, Assaf Gold Shadow CD 1669 Azcano, Juli Distancias CD 1851 Azcano, Julio/Arroyo, M. New Tango Songbook CD 1850 Baba Shrimps Neon CD 1570 Baker, Bastian Tomorrow may not be better CD 1397 Baker, Bastian Noël’s Room CD 1481 Baker, Bastian Too old to die young CD 1531 Baker, Bastian Facing Canyons CD 1702 Bailey Rae, Corinne The Heart speaks in Whispers CD 1733 Barclay James H. -

Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

HARMONIC RESOURCES IN 1980S HARD ROCK AND HEAVY METAL MUSIC A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Theory by Erin M. Vaughn December, 2015 Thesis written by Erin M. Vaughn B.M., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________ Richard O. Devore, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Director, School of Music _____________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER I........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................ 3 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................... 36 ANALYSIS OF “MASTER OF PUPPETS” ...................................................................................... -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian .