Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Jazz History and Research Graduate Program in Arts written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and Dr. Henry Martin And approved by Newark, New Jersey May 2016 ©2016 Zachary Streeter ALL RIGHT RESERVED ABSTRACT Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zach Streeter Thesis Director: Dr. Lewis Porter Despite the institutionalization of jazz music, and the large output of academic activity surrounding the music’s history, one is hard pressed to discover any information on the late jazz guitarist Jimmy Raney or the legacy Jimmy Raney left on the instrument. Guitar, often times, in the history of jazz has been regulated to the role of the rhythm section, if the guitar is involved at all. While the scope of the guitar throughout the history of jazz is not the subject matter of this thesis, the aim is to present, or bring to light Jimmy Raney, a jazz guitarist who I believe, while not the first, may have been among the first to pioneer and challenge these conventions. I have researched Jimmy Raney’s background, and interviewed two people who knew Jimmy Raney: his son, Jon Raney, and record producer Don Schlitten. These two individuals provide a beneficial contrast as one knew Jimmy Raney quite personally, and the other knew Jimmy Raney from a business perspective, creating a greater frame of reference when attempting to piece together Jimmy Raney. -

The Beatles Piano Duets: Intermediate Level Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE BEATLES PIANO DUETS: INTERMEDIATE LEVEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Beatles | 75 pages | 01 Aug 1998 | Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation | 9780793583386 | English | United States The Beatles Piano Duets: Intermediate Level PDF Book Piano Duet. Composed by Various. Digital Sheet Music. The Beatles for Easy Classical Piano. Taylor Swift for Piano Duet. Close X Tell A Friend. Location: optional. Duet, Pop. The Beatles for Classical Guitar. Arranged by Phillip Keveren. Duet, Pop. If you have any suggestions or comments on the guidelines, please email us. I am a music teacher. Pop, Rock. With Playground, you are able to identify which finger you should be using, as well as an onscreen keyboard that will help you identify the correct keys to play. Solo trombone songbook no accompaniment, softcover. String Duet. You can also listen to your MP3 at any time in your Digital Library. With vocal melody, lyrics, standard notation and chord names. A Thousand Years 1 piano 4 hands. Softcover with CD. Piano Duet Play-Along. Solo Songbook. This name will appear next to your review. By The Beatles. Members Save Big! Published by Alfred Music. Intermediate; Late Intermediate. With vocal melody, piano accompaniment, lyrics, chord names and guitar chord diagrams. Support was perfect solving issues with shipping. The Best of the Beatles - 2nd Edition. We cannot post your review if it violates these guidelines. C Instruments C Instruments. Trumpet - Difficulty: medium Trumpet. Finally, when you've mastered Let It Be, you can record yourself playing it and share it with your friends and family. Best of The Beatles - Trombone. Piano Duet Play-Along Volume 4. -

Catalogue of Works Barry Peter Ould

Catalogue of Works Barry Peter Ould In preparing this catalogue, I am indebted to Thomas Slattery (The Instrumentalist 1974), Teresa Balough (University of Western Australia 1975), Kay Dreyfus (University of Mel- bourne 1978–95) and David Tall (London 1982) for their original pioneering work in cata- loguing Grainger’s music.1 My ongoing research as archivist to the Percy Grainger Society (UK) has built on those references, and they have greatly helped both in producing cata- logues for the Society and in my work as a music publisher. The Catalogue of Works for this volume lists all Grainger’s original compositions, settings and versions, as well as his arrangements of music by other composers. The many arrangements of Grainger’s music by others are not included, but details may be obtained by contacting the Percy Grainger Society.2 Works in the process of being edited are marked ‡. Key to abbreviations used in the list of compositions Grainger’s generic headings for original works and folk-song settings AFMS American folk-music settings BFMS British folk-music settings DFMS Danish folk-music settings EG Easy Grainger [a collection of keyboard arrangements] FI Faeroe Island dance folk-song settings KJBC Kipling Jungle Book cycle KS Kipling settings OEPM Settings of songs and tunes from William Chappell’s Old English Popular Music RMTB Room-Music Tit Bits S Sentimentals SCS Sea Chanty settings YT Youthful Toneworks Grainger’s generic headings for transcriptions and arrangements CGS Chosen Gems for Strings CGW Chosen Gems for Winds 1 See Bibliography above. 2 See Main Grainger Contacts below. -

Reading Activity Title: Yngwie J. Malmsteen Level. Intermediate +

Reading activity Title: Yngwie J. Malmsteen Level. Intermediate + Objective. To practice reading comprehension and identify the past form of the verb and the regular and irregular forms. Instructions: Read the text carefully and answer the questions below. Yngwie J. Malmsteen Yngwie Johann Malmsteen (born Lars Johann Yngve Lannerbäck, June 30, 1963) is a Swedish guitarist, composer and bandleader. Widely recognized as a virtuoso, Malmsteen achieved widespread acclaim in the 1980s due to his technical proficiency and his pioneering neo-classical metal. Guitar One magazine rated him the third fastest guitar shredder in the world after Michael Angelo Batio and Chris Impellitteri. Born into a musical family in Stockholm, Yngwie was the youngest child in the family. At an early age, he showed little interest in music. It wasn't until September 18, 1970 when at age seven he saw a TV special on the death of Jimi Hendrix that Malmsteen became obsessed with the guitar. To quote his official website, "The day Jimi Hendrix died, the guitar-playing Yngwie was born". He claims his first name in Swedish means "young Viking chief". Actually, it is a variation of Yngvi, who founded the House of Yngling, which is the oldest known Swedish dynasty. Malmsteen was in his teens when he first encountered the music of the 19th- José Ramón Montero Del Angel | Universidad Veracruzana century violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini, whom he cites as his biggest classical influence. It has been rumoured that Yngwie believes himself to be the reincarnation of the temperamental, often criticized,and widely misunderstood violinist from Genoa. Through his emulation of Paganini concerto pieces on guitar, Malmsteen developed a prodigious technical fluency. -

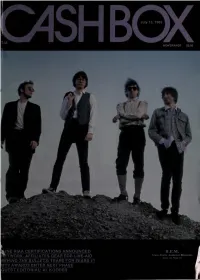

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth Metallica

(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth Metallica (How Sweet It Is) To Be Loved By You Marvin Gaye (Legend of the) Brown Mountain Light Country Gentlemen (Marie's the Name Of) His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now and Then There's) A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (You Drive ME) Crazy Britney Spears (You're My) Sould and Inspiration Righteous Brothers (You've Got) The Magic Touch Platters 1, 2 Step Ciara and Missy Elliott 1, 2, 3 Gloria Estefan 10,000 Angels Mindy McCreedy 100 Years Five for Fighting 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love (Club Mix) Crystal Waters 1‐2‐3 Len Barry 1234 Coolio 157 Riverside Avenue REO Speedwagon 16 Candles Crests 18 and Life Skid Row 1812 Overture Tchaikovsky 19 Paul Hardcastle 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1985 Bowling for Soup 1999 Prince 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 1B Yo‐Yo Ma 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Minutes to Midnight Iron Maiden 2001 Melissa Etheridge 2001 Space Odyssey Vangelis 2012 (It Ain't the End) Jay Sean 21 Guns Green Day 2112 Rush 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 21st Century Kid Jamie Cullum 21st Century Schizoid Man April Wine 22 Acacia Avenue Iron Maiden 24‐7 Kevon Edmonds 25 or 6 to 4 Chicago 26 Miles (Santa Catalina) Four Preps 29 Palms Robert Plant 30 Days in the Hole Humble Pie 33 Smashing Pumpkins 33 (acoustic) Smashing Pumpkins 3am Matchbox 20 3am Eternal The KLF 3x5 John Mayer 4 in the Morning Gwen Stefani 4 Minutes to Save the World Madonna w/ Justin Timberlake 4 Seasons of Loneliness Boyz II Men 40 Hour Week Alabama 409 Beach Boys 5 Shots of Whiskey -

To a Wild Rose Guitar Solo Sheet Music

To A Wild Rose Guitar Solo Sheet Music Download to a wild rose guitar solo sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 1 pages partial preview of to a wild rose guitar solo sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2883 times and last read at 2021-09-24 18:38:29. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of to a wild rose guitar solo you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Acoustic Guitar, Classical Guitar, Fingerpicking Guitar, Guitar Solo, Guitar Tablature Ensemble: Mixed Level: Early Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music My Wild Irish Rose For Guitar With Background Track Jazz Pop Version My Wild Irish Rose For Guitar With Background Track Jazz Pop Version sheet music has been read 3433 times. My wild irish rose for guitar with background track jazz pop version arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 23:38:38. [ Read More ] My Wild Irish Rose For Jazz Guitar My Wild Irish Rose For Jazz Guitar sheet music has been read 2971 times. My wild irish rose for jazz guitar arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 3 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 17:49:26. [ Read More ] To A Wild Rose For Guitar Ensemble 4 Guitars To A Wild Rose For Guitar Ensemble 4 Guitars sheet music has been read 3246 times. To a wild rose for guitar ensemble 4 guitars arrangement is for Intermediate level. -

Iq Flash Music 4-15 464 Songs, 1.2 Days, 3.33 GB

Page 1 of 13 iQ Flash Music 4-15 464 songs, 1.2 days, 3.33 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 001 Pester Karneval 10:40 Waves Of The Danube (CD13002) 2 002 Hungarian Dance No.6 3:22 Waves Of The Danube (CD13002) 3 003 Hungarian Dance No.5 5:25 Waves Of The Danube (CD13002) 4 004 Hungarian Dance No.1 3:10 Waves Of The Danube (CD13002) 5 005 Emperor Waltz 11:23 Waves Of The Danube (CD13002) 6 006 Blue Danube Waltz 12:57 Waves Of The Danube (CD13002) 7 007 Sonata in F Maj K505 2:33 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 8 008 Sonata in E Maj K496 4:19 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 9 009 Sonata in E Maj K495 3:08 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 10 010 Sonata in C Maj K502 3:52 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 11 011 Sonata in C Maj K501 4:57 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 12 012 Sonata in C Maj K487 3:38 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 13 013 Sonata in C Maj K486 4:19 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 14 014 Sonata in BbMaj K504 2:21 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 15 015 Sonata in BbMaj K488 3:17 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 16 016 Sonata in b min K498 3:11 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 17 017 Sonata in b min K497 3:38 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 18 018 Sonata in A Maj K500 3:22 The Sonata: Domenico Scarlatti (PD3021) 19 019 K576 - Allegro 3:45 The Great Composers: W.A. -

Building a Blues Solo Across 2 Choruses

Building a blues solo across 2 choruses The most common length for a blues guitar solo is two choruses (twice round the 12 bars). This lesson looks at some concepts that can be used to build a solo. We’ll use Eric Clapton’s solo on “Tore Down” (from the album “From the Cradle”) to discuss some of the following concepts (but I could have picked any number of great blues solos, which all exhibit similar characteristics): Ø Question and Answer Ø Telling a Story Ø Rhythm Ø Register Ø Climax Ø Rests Ø Dynamics Ø Concise phrases Question and Answer “Call and response” is at the heart of the blues. Playing a phrase and then “answering” it with another phrase is a great way to develop ideas in a coherent manner in any style. Clapton does this throughout the solo, with just about every phrase being “answered”, and some phrases (eg #7) consisting of a question and answer within them. Telling a Story Think of playing licks when improvising as being like introducing characters in a story. You don’t want to introduce too many at one time. Take one idea/character and develop it before adding another. Build on each idea, and have them interact with each other like characters having a conversation. Don’t give everything away right at the beginning, take your time and develop the plot/story/solo. Hear, for example, how Clapton uses Phrase #1 throughout the solo (#7 and #9 are very similar). And also how the solo unfolds in a measured, logical way. -

Music Theory Through the Lens of Film

Journal of Film Music 5.1-2 (2012) 177-196 ISSN (print) 1087-7142 doi:10.1558/jfm.v5i1-2.177 ISSN (online) 1758-860X ARTICLE Music Theory through the Lens of Film FranK LEhman Tufts University [email protected] Abstract: The encounter of a musical repertoire with a theoretical system benefits the latter even as it serves the former. A robustly applied theoretic apparatus hones our appreciation of a given corpus, especially one such as film music, for which comparatively little analytical attention has been devoted. Just as true, if less frequently offered as a motivator for analysis, is the way in which the chosen music theoretical system stands to see its underlying assumptions clarified and its practical resources enhanced by such contact. The innate programmaticism and aesthetic immediacy of film music makes it especially suited to enrich a number of theoretical practices. A habit particularly ripe for this exposure is tonal hermeneutics: the process of interpreting music through its harmonic relationships. Interpreting cinema through harmony not only sharpens our understanding of various film music idioms, but considerably refines the critical machinery behind its analysis. The theoretical approach focused on here is transformation theory, a system devised for analysis of art music (particularly from the nineteenth century) but nevertheless eminently suited for film music. By attending to the perceptually salient changes rather than static objects of musical discourse, transformation theory avoids some of the bugbears of conventional tonal hermeneutics for film (such as the tyranny of the “15 second rule”) while remaining exceptionally well calibrated towards musical structure and detail.