Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles' Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifying Beatles New Zealand 45'S

Identifying New Zealand Beatles 45's Page Updated 23 De 16 Red and Silver Parlophone Label The Beatles first began hitting it big in New Zealand in the middle of 1963. During the early 1960's, New Zealand Parlophone was issuing singles on a red label with "Parlophone" at the top. The writing on this issue is in silver print. The singles originally issued on this label style were as follows: Songs Catalog Number "Please Please Me"/"Ask Me Why" NZP 3142 "From Me to You"/"Thank You Girl" NZP 3143 "She Loves You"/"I'll Get You" NZP 3148 "I Want to Hold Your Hand"/"This Boy" NZP 3152 "I Saw Her Standing There"/"Love Me Do" NZP 3154 "Can't Buy Me Love"/"You Can't Do That" NZP 3157 "Roll Over Beethoven"/"All My Loving" NZP 3158 "Twist and Shout"/"Boys" NZP 3160 "Money"/"Do You Want to Know a Secret" NZP 3163 "Long Tall Sally"/"I Call Your Name" NZP 3166 "Hard Day's Night"/"Things We Said Today" NZP 3167 "I Should Have Known Better"/"And I Love Her" NZP 3172 "Matchbox"/"I'll Cry Instead" NZP 3173 Red, Silver, and Black Parlophone Label At the end of 1964, the Parlophone label went through a transition period. Black lettering was used for the singles' information on the existing red-and-silver backdrops. Notice that "Parlophone" still appears in silver at the top of the label. The following singles were released originally on this label style. Songs Catalog Number "I Feel Fine"/"She's a Woman" NZP 3175 Red and Black Parlophone Label Once again in 1965, New Zealand Parlophone changed label styles. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Carnegie Hall Concert with Buck Owens and His Buckaroos”—Buck Owens and His Buckaroos (1966) Added to the National Registry: 2013 Essay by Scott B

“Carnegie Hall Concert with Buck Owens and His Buckaroos”—Buck Owens and His Buckaroos (1966) Added to the National Registry: 2013 Essay by Scott B. Bomar (guest post) * Original album Original label Buck Owens and His Buckaroos In the fall of 1965, Buck Owens was the biggest country star in the world. He was halfway through a string of sixteen consecutive #1 singles on the country chart in the industry-leading “Billboard” magazine, and had just been invited to appear at New York City’s prestigious Carnegie Hall. Already designated a National Historic Landmark, the esteemed venue had hosted Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky, Gershwin, Bernstein, and Ellington. Owens recognized the honor of being asked, but instructed his manager, Jack McFadden, to decline the offer. “When they first started talking about it, it scared me to death,” he admitted in a 1967 radio interview with Bill Thompson. Buck was worried the Manhattan audience wouldn’t be interested in his music, and he wanted to avoid the embarrassment of unsold tickets. McFadden pushed him to reconsider. When Ken Nelson, Owens’ producer at Capitol Records, suggested they record the performance and release it as his first live album, Buck finally conceded. Buck Owens’ journey to the top of the charts and the top of the bill at the most revered concert hall in the United States began in Sherman, Texas, where he was born Alvis Edgar Owens, Junior in 1929. By 1937, the Owens family was headed for a new life in California, but they wound up settling in Mesa, Arizona, when a broken trailer hitch derailed their plan. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

Audacity Find Clipping

Audacity find clipping Continue See also: List of songs about California Wikimedia related to the song list article This is a list of songs about Los Angeles, California: either refer, are set there, named after a place or feature of a city named after a famous resident, or inspired by an event that occurred locally. In addition, several adjacent communities in the Greater Los Angeles area, such as West Hollywood, Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, Pasadena, Inglewood and Compton are also included in this list, despite the fact that they are separate municipalities. The songs are listed by those who are notable or well-known artists. Songs #s-A 10th and Crenshaw Fatboy Slim 100 Miles and Runnin' at N.W.A 101 Eastbound on Fourplay 103rd St. Theme Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band 1977 Sunset Strip at Low Numbers 2 A.M. on Bobby Mulholland Drive Please, and Udenik 2 David Banner 21 Snoopstreet Trey Deee 26 Miles (Santa Catalina) at Four Preps 2 Nigs United 4 West Compton Prince 29th Street David Benoit 213 to 619 Adjacent Abstract. at Los Angeles Joe Mama 30 Piers Avenue Andrew Hill 319 La Cienega Tony, Vic and Manuel 34th Street in Los Angeles Dan Cassidy 3rd Base, Dodger Stadium Joe Kewani (Rebuilt Paradise Cooder) 405 by RAC Andre Allan Anjos 4pm in Calabasas Drake (musician) 5 p.m. to Los Angeles Julie Covington 6 'N Mornin' by Ice-T 64 Bars at Wilshire Barney Kessel 77 Sunset Strip from Alpinestars 77 Sunset Sunset Strip composers Mack David and Jerry Livingston 79th and Sunset Humble Pye 80 blocks from Silverlake People under the stairs 808 Beats Unknown DJ 8069 Vineland round Robin 90210 Blackbeard 99 miles from Los Angeles Art Garfunkel and Albert Hammond Malibu Caroline Loeb .. -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

Kristine Stiles

Concerning Consequences STUDIES IN ART, DESTRUCTION, AND TRAUMA Kristine Stiles The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London KRISTINE STILES is the France Family Professor of Art, Art Flistory, and Visual Studies at Duke University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2016 by Kristine Stiles All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 12345 ISBN13: 9780226774510 (cloth) ISBN13: 9780226774534 (paper) ISBN13: 9780226304403 (ebook) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226304403.001.0001 Library of Congress CataloguinginPublication Data Stiles, Kristine, author. Concerning consequences : studies in art, destruction, and trauma / Kristine Stiles, pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9780226774510 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226774534 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226304403 (ebook) 1. Art, Modern — 20th century. 2. Psychic trauma in art. 3. Violence in art. I. Title. N6490.S767 2016 709.04'075 —dc23 2015025618 © This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper). In conversation with Susan Swenson, Kim Jones explained that the drawing on the cover of this book depicts directional forces in "an Xman, dotman war game." The rectangles represent tanks and fortresses, and the lines are for tank movement, combat, and containment: "They're symbols. They're erased to show movement. 111 draw a tank, or I'll draw an X, and erase it, then redraw it in a different posmon... -

The Irony and Drug Related Themes of Photographs of the Rolling Stones ARTE 214 DECLAN RILEY

The Irony and Drug Related Themes of photographs of The Rolling Stones ARTE 214 DECLAN RILEY For our assignment we were tasked with comparing 2 photographs displayed in class. For this assignment I have chosen to compare similar photos; one of Keith Richards taken by Ethan Russel in 1972, ironically posing in front of an anti-drug poster, and the other, a portrait of Mick Jagger taken by Annie Lebovitz also taken in 1972. In this comparison, not only will I be discussing comparisons and contrasts between these two pieces but I will be highlighting the underlying theme of irony that both photos present. In 1962, the world was introduced to a band that would go on to the one of the most iconic and influential rock bands to date. Formed in London, The Rolling Stones appeared on the music scene around the same time that The Beatles were also growing in popularity. Driven by founders Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, The Rolling Stones started locally in London quickly became a worldwide phenomenon. Still a band to this day The Rolling Stone have begun to play less shows and members have begun to slow down with old age and have concentrations on their own personal music.1 The Rolling Stones are regarded as one of the most influential rock bands of all time and not only influenced the music industry but also have become a permanent fixture in ‘pop-culture’. As the photos I have chosen begin to be examined, described and compared; it is important to keep in mind the immense stardom that these musicians experienced. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

Los Angeles City Clerk

CITY OF LOS ANGELES BOARD OF DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING AND SAFETY CALIFORNIA BUILDING AND SAFETY COMMISSIONERS 201 NORTH FIGUEROA STREET LOS ANGELES, CA 90012 VAN AMBATIELOS PRESIDENT E. FELICIA BRANNON FRANK M. BUSH VICE PRESIDENT GENERAL MANAGER JOSEL YN GEAGA-ROSENTHAL ERIC GARCETTI OSAMA YOUNAN, P.E. GEORGE HOVAGUIMIAN MAYOR EXECUTIVE OFFICER JAVIER NUNEZ October 13, 2016 BOARD FILE NO. 160073 C.D.: 4 (Councilmember D. Ryu) Board ofBuilding and Safety Commissioners Room 1080, 201 North Figueroa Street APPLICATION TO EXPORT 3,500 CUBIC YARDS OF EARTH PROJECT LOCATION: 1561 NORTH BLUE JAY WAY TRACT: TR 19229 BLOCK: NONE LOT: 40 OWNER: Crystal Clear LLC. C/0: Harry Morton 9049 Elevado Street West Hollywood, CA 90069 APPLICANT: Tony Russo 11150 West Olympic Boulevard, #700 Los Angeles, CA 90064 The Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Department of Public Works (DPW) have reviewed the subject haul route application and have forwarded the following recommendations to be considered by the Board of Building and Safety Commissioners (Board) in order to protect the public health, safety and welfare. LADBS G-5 (Rev.OS/14/2013) AN EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY- AFFIRMATIVE ACTION EMPLOYER Page2 Job Address: 1561 NORTH BLUE JAY WAY Board File: 160073 CONDITIONS OF APPROVAL Additions or modifications to the following conditions may be made on-site at the discretion of the Grading Inspector, if deemed necessary to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the general public along the haul route. Failure to comply with any conditions specified in this report may void the Board's action. If the hauling operations are not in accordance with the Board's approval, The Department of Building and Safety (DBS) shall list the specific conditions in violation and shall notify the applicant that immediate compliance is required. -

View Entire Issue As

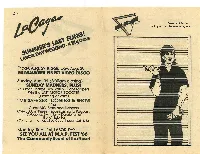

6 Li Volume 3, Issue 16 0 1 0 August 21 - September 3, 1986 ANIMINC't A ik3L___ 4111 11114 - ' i ) :... - Friday, Aug. 29 & Saturday, Aug. 30 MILWAUKEE'S FINEST VIDEO DISCO 11.0. 14r•a- : c Sunday, Aug. 31 (3:30am closing) _ SUNDAY MADNESS, PLUS! $1 Door Charge, 75 Rail & Giant Tappers Win the LAST MOTOR SCOOTER (Drawing at 2am) I "MR SAFE SEX" CONTEST & SHOW 11pm Guest MC, Stars and Dancers ...._ Over $300 in Prizes + sponsorship to Pageant Categories: Swim Suit + Description of "Erotic" Safe Sex (Contestant sign-up at La Cage through Sat. 8/30) -.., Monday, Sept. 1st, LABOR DAY SEE YOU ALL AT M.A.P. FEST '86 The Community Event of the Year! Page 2 • August 21 - September 3, 1986 • InStep 63 IN STEP PUBLISHER & EDITOR Staff cartoonist Tom Rezza created this Ron Geiman issues cover to salute and commemorate the American Women in t -le work place. AIDE-de-"CAMP" Joe Koch COLUMNISTS Ken Kurtz Kevin Michael W.W. Wells III Note: Dan Brown Dee Dailey Carl Ohly Deadline for the next issue CARTOONIST Issue 17 Wisconsin's gay/lesbian bi-weekly Tom Rezza the September 4th Issue is 5pm, August 27th PHOTOGRAPHY Call our office at 931-8115 for any other Carl Ohly information. Business Owners . • GRAFFITTI EDITOR Events occuring after August 14th are not in Katie this issue. TYPESETTING C i X . I. D.S. If you've never advertised in INSTEP, you Alpha Composition HOTLINES just may be pleasantly suprised at the results. AD REPRESENTATIVE TOLL FREE Ron Geiman mit. -

Milestone Film and the British Film Institute Present

Milestone Film and the British Film Institute present “She was born with magic hands.” — Jean Renoir on Lotte Reiniger A Milestone Film Release PO Box 128 • Harrington Park, NJ 07640 • Phone: (800) 603-1104 or (201) 767-3117 Fax: (201) 767-3035 • Email: [email protected] • www.milestonefilms.com The Adventures of Prince Achmed Die Abenteur des Prinzen Achmed (1926) Germany. Black and White with Tinting and Toning. Aspect Ratio: 1:1.33. 72 minutes. Produced by: Comenius-Film Production ©1926 Comenius Film GmbH © 2001 Primrose Film Productions Ltd. Based on stories in The Arabian Nights. Crew: Directed by ........................................Lotte Reiniger Animation Assistants..........................Walther Ruttmann, Berthold Bartosch and Alexander Kardan Technical Advisor..............................Carl Koch Original Music by..............................Wolfgang Zeller Restoration by the Frankfurt Filmmuseum. Tinted and printed by L'immagine ritrovata in Bologna. The original score has been recorded for ZDF/Arte. Scissors Make Films” By Lotte Reiniger, Sight and Sound, Spring 1936 I will attempt to answer the questions, which I am nearly always asked by people who watch me making the silhouettes. Firstly: How on earth did you get the idea? And secondly: How do they move, and why are your hands not seen on screen? The answer to the first is to be found in the short and simple history of my own life. I never had the feeling that my silhouette cutting was an idea. It so happened that I could always do it quite easily, as you will see from what follows. I could cut silhouettes almost as soon as I could manage to hold a pair of scissors.