Papers in Kosraean and Ponapeic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direktori Konstruksi

http://www.bps.go.id http://www.bps.go.id http://www.bps.go.id DIREKTORI PERUSAHAAN KONSTRUKSI 2012 Directory of Construction Establishment 2012 Buku IV (Pulau Kalimantan) Book IV (Pulau Kalimantan) ISBN. 978-979-064-175-7 No. Publikasi / Publication Number : 05340.1005 Katalog BPS / BPS Catalogue : 1305055 Ukuran Buku / Book Size : 21 cm X 29 cm Jumlah Halaman / TotalPage : (xv + 366) halaman / pages Naskah / Manuscript : Subdirektorat Statistik Konstruksi Subdirectorate of Construction Statistics Gambar Kulit / Cover Design : Subdirektorat Statistik Konstruksi Subdirectorate of Construction Statistics Diterbitkan oleh / Published by : http://www.bps.go.id Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, Indonesia BPS-Statistics Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia Boleh dikutip dengan menyebut sumbernya May be cited with reference to the sources KATA PENGANTAR Direktori Perusahaan Konstruksi 2012 ini merupakan perbaikan dari Direktori Perusahaan Konstruksi 2011 berdasarkan hasil Survei Updating Direktori Perusahaan Konstruksi Tahun 2012 dan Survei Perusahaan Konstruksi Tahun 2012. Direktori ini merupakan identifikasi perusahaan yang meliputi: KIP, Nama, Alamat, Nomor Telepon, Nomor Faximile, dan Alamat Email Perusahaan. Diharapkan Publikasi ini bermanfaat baik oleh perusahaan bersangkutan maupun konsumen data yang memerlukan untuk kegiatan sehari-harinya. Disamping itu direktori ini diharapkan dapat digunakan juga sebagai kerangka sampel bagi penelitian atau studi-studi khusus selanjutnya. Akhirnya pada kesempatan ini kami mengucapkan terima kasih dan penghargaan kepada semua pihak terutama kepada para Pengusaha dan Pimpinan Perusahaan Jasa Konstruksi yang telah membantu kelancaran pelaksanaan survei tersebut, dan menghimbau di masa mendatang agar dapat memberikan data yang akurat, lengkap dan reliable serta dapat memberikan masukan untuk perbaikan publikasi ini. http://www.bps.go.id Jakarta, September 2012 Kepala Badan Pusat Statistik Republik Indonesia DR. -

An Annotated Bibliography on ESL and Bilingual Education in Guam and Other Areas of Micronesia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299 832 FL 017 646 AUTHOR Goetzfridt, Nicholas TITLE An Annotated Bibliography on ESL and Bilingual Education in Guam and Other Areas of Micronesia. SPONS AGENCY Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Languages Affairs (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 112p.; A publioation of Project BEAM. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Bilingual Education; *English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Publications; *Resource Materials; Second Language Instruction IDENTIFIERS *Guam; *Micronesia ABSTRACT The bibliography contains 182 annotated and 52 unannotated citations of journal articles, newspaper articles, dissertations, books, program and research reports, and other publications concerning bilingual education and instruction in English as a second language (ESL) in Micronesia. An introductory section gives information on sources for the publications and other information concerning the use of the bibliography. The entries are indexed alphabetically. (MSE) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** An Annotated Bibliography on ESL and Bilingual Education in Guam and Other Areas of Micronesia "PER? ISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS U.S. DEPARTMENTOF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY Othce of Educabona. Research and improvement EDUCATIONAL -

Elak Sra Onak Project

UNIVF:RSITY OF HAWAl'I LIBRARY ELAK SRA ONAK PROJECT Volume one, Issue two September 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENT TIW proj«t u funded i11 whole or in part by tlte US National Park Savka and tM Kosru State Govan1M11t, DepartJMnt of Agriculture Land & Fisheries ,. INTRODUCTION The Elak Sra Onak Project is happy to present to you the Volume one, Issue two Elak Sra Onak Book. This issue is a continuation ofvolume one. This issue is specifically discusses four of Kosrae's areas of Culture. These four areas are: Ideology which presents mostly on the Religious activities, Beliefs, Changes is religion such as new churches and conversions, other aspects of ideology such as stories about people and events in different times, and ideas about the proper way people should act toward one another. Another area is the Cultural Transmission which discusses how culture is passed on to new generations, formal and informal education ofways ofmaking a living, values, and social structure, how are schools organized in Kosrae, who are the teachers, how are they trained, where does the curriculum come from, how do school activities relate to informal education in homes and other places, what are Kosrae's games and how do they reflect Kosrae culture. The last section talks about Social Structure and Changes which will present to you, how has Kosrae changed, what are some of the things that are causing the changes today such as the video cassette recorders(VCRs), the ctrcumfrenttal road or the new airport, who are the people who introduce changes, how is change accepted by different people in each village, how does each village react to change, the role of institutions and their acceptance or resistance to change. -

P O R T O F O L

porto folio Kampung Potronanggan RT 006 No.1, Tamanan, Banguntapan, Bantul, DI Yogyakarta 55191 [email protected] | +62 818 260 261 (Tomo) TABLE OF CONTENT Background Vision - Mission – Method Organisaon Structure COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES Post Disaster Poor Kampung / Informal Comprehensive Planning Heritage Conservaon Workshop and Training Network Meeng and Visits Compeon, Exhibion and Seminar ARCHITECTURAL PROJECTS Alternave Technology Development Architectural Project Design Architecture has a wide scope knowledge. Experts classified it as multi-dimension because the purpose is to accommodate community’s daily activities like housing, working, praying, trading, and others. Allocation of Architecture knowledge should also reach all community’s layers which is related to human’s life. Community Architect is an alternative to mainstream architects, but still one of architect professions. Architect is commonly known as commercial job. Community architect is a movement-oriented group with personal dedication as a response to social issues at large. Example in natural disaster which is incidental phenomenon with the need of fast treatment and recovery process as soon as possible. However beside natural disaster, the increasing of number and density of urban poor kampung in Indonesia so eviction be a social disaster. Limitedness of formal approach in planning and management of the city arise alternative needs and holistic approach that more concerned to community values and socio-cultural BACKGROUND aspects. Arkomjogja Tsunami Aceh at 26 Desember 2004 was required us as people to stand and give fully solidarity for able helping suit to sector/expertise. Labor mobilization with various expertise massive happened to think hard for rebuild their life. This is where we gather from. -

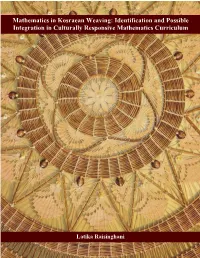

Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving: Identification and Possible

Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving: Identification and Possible Integration in Culturally Responsive Mathematics Curriculum Latika Raisinghani 1 Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving: Identification and Possible Integration in Culturally Responsive Mathematics Curriculum Latika Raisinghani Assistant Professor Education and Science Department College of Micronesia-FSM Kosrae FM 96944 Micronesia E-mail: [email protected] 2 Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving Introduction This paper focuses on identification and description of mathematical ideas, patterns and thinking involved in the making of specific artifacts of weaving (otwot) in Kosrae, using coconut leaves and fibers (sroacnu), pandanus leaves (lol) and hibiscus bast (ne), and their possible integration in a culturally responsive Mathematics curriculum. Kosrae (pronounced as Ko-shry), also called the “Island of the Sleeping Lady”, is the only island state within the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) that does not have any outer islands. It is of volcanic origin and is believed to have been formed by the shifting of the great Pacific Tectonic Plate, which was later called the Caroline Plate, approximately 3,000,000 years ago. Kosrae had many other names as well: Kusaie, Katau, Kato, Kosiu, Kusae, Carao Tevya, Strong’s Island, Hope Island; however, the people who found it used none of these. They called it Kosrae (Segal, 1995). Dr. Ernst Sarfert described Kosrae as “the most beautiful island of the great ocean, as honoring its name ‘Gem of the Pacific’ indicates, which it received at the time of its highest popularity with the white people” (Sarfert, 1919). Kosrae covers an area of 42.31 square miles and is roughly triangular in shape. -

Pacific Youth: Local and Global Futures

PACIFIC YOUTH LOCAL AND GLOBAL FUTURES PACIFIC YOUTH LOCAL AND GLOBAL FUTURES EDITED BY HELEN LEE PACIFIC SERIES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463212 ISBN (online): 9781760463229 WorldCat (print): 1125205462 WorldCat (online): 1125270333 DOI: 10.22459/PY.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: ‘Two local youths explore their backyard beach in Tupapa, Rarotonga’ by Ioana Turia This edition © 2019 ANU Press Contents 1. Pacific Youth, Local and Global ..........................1 Helen Lee and Aidan Craney 2. Flexibility, Possibility and the Paradoxes of the Present: Tongan Youth Moving into the Future .....................33 Mary K Good 3. Economic Changes and the Unequal Lives of Young People among the Wampar in Papua New Guinea. 57 Doris Bacalzo 4. ‘Things Still Fall Apart’: A Political Economy Analysis of State—Youth Engagement in Honiara, Solomon Islands .......79 Daniel Evans 5. The New Nobility: Tonga’s Young Traditional Leaders ........111 Helen Lee 6. Youth Leadership in Fiji and Solomon Islands: Creating Opportunities for Civic Engagement. 137 Aidan Craney 7. Entrepreneurship and Social Action Among Youth in American Sāmoa .................................159 Aaron John Robarts Ferguson 8. Youth’s Displaced Aggression in Rural Papua New Guinea ....183 Imelda Ambelye 9. From Drunken Demeanour to Doping: Shifting Parameters of Maturation among Marshall Islanders ..................203 Laurence Marshall Carucci 10. -

A Case Study from Micronesia the Following: David A

In this issue – Grass Roots Language Preservation – Bilingual Living in a ‘Monolingual’ Country – Multicultural Adoption News and Views for Intercultural People – Too Much of a Good Thing? Editors: Sami Grover & Marjukka Grover 2003, Vol 20 No.3 – News from the USA EDITORIAL PRESERVING LANGUAGE FROM THE BOTTOM UP: All too often bi/multilinguals are asked A Case Study From Micronesia the following: David A. Hough and Alister Tolenoa ‘What exactly is the point of preserving your Spanish/ German/ Arabic/ Urdu ?’ Pohnpeian, with Kiribati, Nauruan and (delete as appropriate) Chuukese also related. In a world where English predominates, Much of Kosrae’s early history has been monolinguals can find it hard to lost because of colonisation and understand that language can mean so depopulation. From 1840–1880 the much more than just being a tool for population decreased from about 7000 to communication. For many of us, our 300 due to diseases brought by Western multiple languages are important links to whaling ships. Direct colonial rule our heritage and our cultural identities. followed, first under Spain until 1898, They are part of who we are. then Germany until 1914, Japan from 1914 until 1945, and following that the In this issue we hear from David Hough Official efforts to preserve a language, and Alister Tolenoa on a language United States. The legacy of this or anything else for that matter, are colonialism is still very much alive. program in Micronesia that is often led from the top down by empowering the inhabitants of a tiny government and experts who may not Today, the island is part of the Federated island to preserve their own language. -

Tungusic Languages

641 TUNGUSIC LANGUAGES he last Imperial family that reigned in Beij- Nanai or Goldi has about 7,000 speakers on the T ing, the Qing or Manchu dynasty, seized banks ofthe lower Amur. power in 1644 and were driven out in 1912. Orochen has about 2,000 speakers in northern Manchu was the ancestral language ofthe Qing Manchuria. court and was once a major language ofthe Several other Tungusic languages survive, north-eastern province ofManchuria, bridge- with only a few hundred speakers apiece. head ofthe Japanese invasion ofChina in the 1930s. It belongs to the little-known Tungusic group Numerals in Manchu, Evenki and Nanai oflanguages, usually believed to formpart ofthe Manchu Evenki Nanai ALTAIC family. All Tungusic languages are spo- 1 emu umuÅn emun ken by very small population groups in northern 2 juwe dyuÅr dyuer China and eastern Siberia. 3 ilan ilan ilan Manchu is the only Tungusic language with a 4 duin digin duin written history. In the 17th century the Manchu 5 sunja tungga toinga rulers ofChina, who had at firstruled through 6 ninggun nyungun nyungun the medium of MONGOLIAN, adapted Mongolian 7 nadan nadan nadan script to their own language, drawing some ideas 8 jakon dyapkun dyakpun from the Korean syllabary. However, in the 18th 9 uyun eÅgin khuyun and 19th centuries Chinese ± language ofan 10 juwan dyaÅn dyoan overwhelming majority ± gradually replaced Manchu in all official and literary contexts. From George L. Campbell, Compendium of the world's languages (London: Routledge, 1991) The Tungusic languages Even or Lamut has 7,000 speakers in Sakha, the Kamchatka peninsula and the eastern Siberian The mountain forest coast ofRussia. -

FSM 2000 Census Report Kosrae

Kosrae State Census Report 2000 FSM Census of Population and Housing December 2002 Kosrae Branch Statistics Office Division of Statistics Department of Economic Affairs National Government Tofol, Kosrae 96944 Federated States of Micronesia 2000 FSM Census of Population and Housing Kosrae State Census Report December 2002 Kosrae Branch Statistics Office Division of Statistics Department of Economic Affairs National Government Tofol, Kosrae State Federated States of Micronesia i iii v vii ix x TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE ................................................................................................................................................. iii GOVERNOR'S MESSAGE.................................................................................................................................................. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT MESSAGE.............................................................................................................................. vii PREFACE………………………………………………………………………………………………………………ix TABLE OF CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................................... xi LIST OF TEXT TABLES................................................................................................................................................... xv LIST OF FIGURES........................................................................................................................................................... -

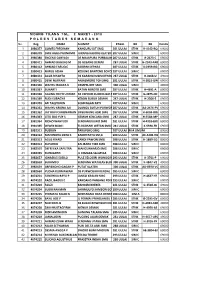

SIDANG TILANG TGL, 2 MARET - 2018 P O L R E S T a B E S S E M a R a N G No

SIDANG TILANG TGL, 2 MARET - 2018 P O L R E S T A B E S S E M A R A N G No. Reg. NAMA ALAMAT PASAL BB BB Denda 1 3980377 GOMES FREDINAN KANGURU SLT SMG 281 UULAJ STNK H-4143-BQ 69000 2 3980378 DWII AGUS PURNOMO JURANG KAJONG KLATEN 287 UULAJ SIM C 69000 3 3980380 ENCENG CAHYADI DS MAJAPURA PURBALINGGA287 UULAJ STNK R-2673-C 69000 4 3980411 AHMAD BAGUAS M DS GEBANG DEMAK 287 UULAJ STNK H-2343-ANE 69000 5 3980412 AHMAD FARUQ C SARIPAN JEPARA 287 UULAJ STNK K-2459-RQ 69000 6 3980413 NURUL AZIAH KEDUNG BANTENG BOYOLALI287 UULAJ SIM C 69000 7 3980414 AGUS RIYANTO DS KARANGDOWO KENDAL 287 UULAJ STNK H-3068-U 49000 8 3980415 DEWI NURYANI ANJASMORO TGH SMG 281 UULAJ STNK H-3853-GW 69000 9 3981366 WAHYU WIJAYA K DEMPEL BRT SMG 300 UULAJ SIM C 49000 10 3981367 SUNARTI BATAN MIROTO SMG 287 UULAJ STNK H-4691-A 69000 11 3981368 AGUNG PRIYO UTOMO DS CEPOKO KUNING BATANG287 UULAJ STNK G-4875-HC 69000 12 3981369 RUDI SUBAGYA KEBON SUBUR DEMAK 287 UULAJ STNK H-2306-E 69000 13 3981370 AFI TAQIYUDIN SOMENGAN PATI 287 UULAJ SIM C 69000 14 3981361 WAHYU KRISNA AJI DLANGU BUTUH PURWOREJO287 UULAJ STNK AA-2476-PV 69000 15 3981362 JAY RAVI CHRISNAWAN SIKLUWUNG ASRI SMG 287 UULAJ STNK H-6069-BIG 69000 16 3981363 CITO EKO YUY S GEMAH KENCANA SMG 287 UULAJ STNK H-5584-MP 69000 17 3981364 RIDHO WAHYUDI SENDANGGUWO SMG 281 UULAJ STNK H-4901-BJG 69000 18 3981365 WIWIN BUDI I TLOGOSARI WETAN SMG 281 UULAJ STNK K-5598-FR 69000 19 3982311 BUSRON TARUPOLO SMG 287 UULAJ SIM A UMUM 89000 20 3982312 MAHENDRA DEWI K BADER RAYA SM,G 288 UULAJ STNK AE-4208-HQ 69000 21 3982313 -

The Boats of the Tawi-Tawi Bajau, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines

The Boats of the Tawi-Tawi Bajau, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines Received 20 February 1990 H. ARLO NIMMO ISLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA has perhaps the greatest variety of watercraft of any culture area in the world. Through centuries of adaptation to tropical riverine and maritime environments, the people of this island world have created hundreds-indeed, prob ably thousands-of different kinds of boats. The primitive rafts that first transported the early inhabitants to offshore islands evolved into the sophisticated sailing vessels that allowed this population to become the most far-flung on earth before the expan sion of European cultures. By the time Europeans began to venture beyond their shores, Austronesian speakers had spread throughout all of Island Southeast Asia, west to Madagascar, north to Taiwan, and east to Micronesia, parts of Melanesia, and the outposts of Polynesia. Perusal of a map of Island Southeast Asia explains the proliferation of watercraft in this area. Thousands of islands make up the modern nations of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia, and one can sail within sight of land throughout the entire area before reaching its outer limits. The lure of these islands to the always curious human mind as well as the abundant food resources in their surrounding waters were doubtless prime motivators for the first boat-builders-as indeed they continue to motivate contemporary boat-builders. Virtually all islands large enough to accommodate human populations are inhabited, and some have been so for mil lennia. The separation of human populations by expanses of water, as well as the diverse currents of history that have moved through the area, has resulted in a rich mosaic of distinctive cultures. -

Paths of Central Caroline Island Children During Migration and Times of Rapid Changei

Paths of Central Caroline Island Children during Migration and Times of Rapid Changei Mary L. Spencer University of Guam Abstract When the post World War II United Nations trusteeship of the US for the Micronesian Region was replaced in 1986 and 1992 by Compacts of Free Association between the US and the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), the Republic of Palau (RP), and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI); and in 1976 by commonwealth status with the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), citizens of these entities were free to reside and work in the United States. The ensuing migration process accelerated rapidly, leading to declining populations in some areas, as documented in the 2000 and 2010 FSM Census reports; and the rise of Micronesian newcomer clusters on Guam, CNMI, Hawaii, and in many continental US states. Today’s Micronesian migration process involves families with children. This paper examines the probable paths and experiences of FSM children in their Central Caroline Island residences compared to life in 2 US locations (Hawaii and Guam), and globalizing back-flow impacts of migration. Focusing on Chuuk, 1 of the 4 FSM states, the author proposes that such an analysis benefits from comparison of child development and experience indicators from everyday life in the origin and destination locations. Promising avenues of future research on migration issues involving Micronesian children and their receiving community and school settings are suggested. Keywords: children; migration; Micronesia This article summarizes the course of modern Micronesian migration and then examines what is known of the lives of Micronesian children and their families following migration stimulated by the US Compacts of Free Association with former U.S.