Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manual for Language Test Development and Examining

Manual for Language Test Development and Examining For use with the CEFR Produced by ALTE on behalf of the Language Policy Division, Council of Europe © Council of Europe, April 2011 The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All correspondence concerning this publication or the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to the Director of Education and Languages of the Council of Europe (Language Policy Division) (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). The reproduction of extracts is authorised, except for commercial purposes, on condition that the source is quoted. Manual for Language Test Development and Examining For use with the CEFR Produced by ALTE on behalf of the Language Policy Division, Council of Europe Language Policy Division Council of Europe (Strasbourg) www.coe.int/lang Contents Foreword 5 3.4.2 Piloting, pretesting and trialling 30 Introduction 6 3.4.3 Review of items 31 1 Fundamental considerations 10 3.5 Constructing tests 32 1.1 How to define language proficiency 10 3.6 Key questions 32 1.1.1 Models of language use and competence 10 3.7 Further reading 33 1.1.2 The CEFR model of language use 10 4 Delivering tests 34 1.1.3 Operationalising the model 12 4.1 Aims of delivering tests 34 1.1.4 The Common Reference Levels of the CEFR 12 4.2 The process of delivering tests 34 1.2 Validity 14 4.2.1 Arranging venues 34 1.2.1 What is validity? 14 4.2.2 Registering test takers 35 1.2.2 Validity -

Language Requirements for CEMS MIM Page 1 of 7

Appendix No. 1. Language requirements for CEMS MIM Page 1 of 7 APPENDIX No. 1 to the CEMS MIM Selection Rules & Regulations LANGUAGE REQUIREMENTS FOR CEMS MIM (last update 2 October 2019) 1. According to the CEMS MIM requirements, all candidates must present one of the following certificates of their proficiency in English, which automatically is their first foreign language (FL 1): a) TOEFL (PBT/CBT/iBT) with the result of 600/250/100 or higher, b) IELTS at 7.0 level or higher, c) CAE at „B” level or higher d) CPE (Grade A, B, C, or C1 Certificate) e) BEC Higher (Grade “A” only) f) GCSE (A-Level) exam issued in Singapore 2. Exemption from the above rule is granted to: a) graduates of undergraduate or graduate level study programmes (with English as the language of instruction) at CEMS member universities/schools, or universities/schools that are EQUIS or AACSB International accredited, or issued in an English-speaking country; b) students who successfully completed CEMS Accredited Course in English at C1 or C2 level (both written and oral). 3. Proof of proficiency in the second foreign language (FL2) is optional and verified on the basis of: a) SGH Language Competence Tests (since September 2017 conducted in a form of control test organised during the 1st semester of MA studies) passed with minimum score 60 points (taken in the calendar year calculated according to the following formula: x-2, where “x” stands for the calendar year in which the selection takes place), b) CNJO certificate on completing SGH tutorials in foreign language for economics (zaświadczenie o ukończeniu lektoratu z języka obcego ekonomicznego) at minimum level of B1, c) commercial tests’ certificates listed in the Table 1 passed at B2 or B1 minimum level, provided they fulfil validity periods, as stipulated in clause 4. -

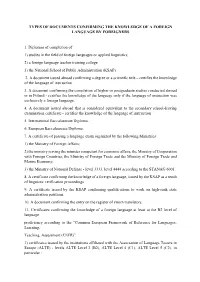

A List of Certificates Confirming the Knowledge of a Modern Foreign Language at the Level of at Least B2, Recognized by the Doctoral School in the Recruitment Process

Appendix no 4 to the Admission Rules to the Doctoral School of the Stanisław Moniuszko Academy of Music in Gdańsk in the academic year 2020/2021 A list of certificates confirming the knowledge of a modern foreign language at the level of at least B2, recognized by the Doctoral School in the recruitment process. Persons who do not have any of the certificates listed below before matriculation will have to pass an exam in a modern foreign language at B2 level, organized by the Foreign Languages Unit of the Stanisław Moniuszko Academy of Music in Gdańsk. This exam will be held in September 20..... Certificates confirming at least B2 level of global language proficiency according to the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)": 1. Certificate confirming the knowledge of a foreign language, issued by the National School of Public Administration as a result of a linguistic verification procedure. 2. Certificates confirming at least B2 level of global language proficiency according to the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)": 1) certificates issued by institutions associated in the Association of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE) - ALTE Level 3 (B2), ALTE Level 4 (C1), ALTE Level 5 (C2), in particular the certificates: a) First Certificate in English (FCE), Certificate in Advanced English (CAE), Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE), Business English Certificate (BEC) Vantage — at least Pass, Business English Certificate (BEC) -

Language Requirements

Language Policy NB: This Language Policy applies to applicants of the 20J and 20D MBA Classes. For all other MBA Classes, please use this document as a reference only and be sure to contact the MBA Admissions Office for confirmation. Last revised in October 2018. Please note that this Language Policy document is subject to change regularly and without prior notice. 1 Contents Page 3 INSEAD Language Proficiency Measurement Scale Page 4 Summary of INSEAD Language Requirements Page 5 English Proficiency Certification Page 6 Entry Language Requirement Page 7 Exit Language Requirement Page 8 FL&C contact details Page 9 FL&C Language courses available Page 12 FL&C Language tests available Page 13 Language Tuition Prior to starting the MBA Programme Page 15 List of Official Language Tests recognised by INSEAD Page 22 Frequently Asked Questions 2 INSEAD Language Proficiency Measurement Scale INSEAD uses a four-level scale which measures language competency. This is in line with the Common European Framework of Reference for language levels (CEFR). Below is a table which indicates the proficiency needed to fulfil INSEAD language requirement. To be admitted to the MBA Programme, a candidate must be fluent level in English and have at least a practical level of knowledge of a second language. These two languages are referred to as your “Entry languages”. A candidate must also have at least a basic level of understanding of a third language. This will be referred to as “Exit language”. LEVEL DESCRIPTION INSEAD REQUIREMENTS Ability to communicate spontaneously, very fluently and precisely in more complex situations. -

English Language Testing in US Colleges and Universities

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 331 284 FL 019 122 AUTHOR Douglas, Dan, Ed. TITLE English Language Testing in U.S. Colleges and Universities. INSTITUTION National Association for Foreign Student Affairs, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY United States information Agency, Washington, DC. Advisory, Teaching, and Specialized Programs Div. REPORT NO /SBN-0-912207-56-6 PUB DATE 90 NOTE 106p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Admission Criteria; College Admission; *English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Foreign Students; Higher Education; *Language Tests; Questionnaires; Second Language Programs; Standardized Tests; Surveys; *Teaching Assistants; *Test Interpretation; Test Results; Writing (Composition); Writing Tests IDENTIFIERS United Kingdom ABSTRACT A collection of essays and research reports addresses issues in the testing of English as a Second Language (ESL) among foreign students in United States colleges and universities. They include the following: "Overview of ESL Testing" (Ralph Pat Barrett); "English Language Testing: The View from the Admissions Office" (G. James Haas); "English Language Testing: The View from the English Teaching Program" (Paul J. Angelis); "Standardized ESL Tests Used in U.S. Colleges and Universities" (Harold S. Madsen); "British Tests of English as a Foreign Language" (J. Charles Alderson); "ESL Composition Testing" (Jane Hughey); "The Testing and Evaluation of International Teaching Assistants" (Barbara S. Plakans, Roberta G. Abraham); and "Interpreting Test Scores" (Grant Henning). Appended materials include addresses for use in obtaining information about English language testing, and the questionnaire used in a survey of higher education institutions, reported in one of the articles. (ME) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

List of Accepted Institutions, Exams and Tests As Evidence to Prove Your Language Proficiency in the CEMS Language and the Third Language

List of accepted institutions, exams and tests as evidence to prove your language proficiency in the CEMS language and the third language Language Type of evidence Accepted by RSM for Accepted by CEMS for entry exit (provided minimum (provided minimum level is reached) level is reached) Various Placement test results and Yes No (there are some languages course certificates from exceptions about university language centres at which you can CEMS schools inform yourself once you are admitted) Placement test results and Yes No course certificates from university language centres at EQUIS or AACSB accredited university TELC language tests Yes No CEMS accredited in-house tests Yes Yes and language courses offered by CEMS-schools (overview available upon request) CEMS MBC test Yes Yes languages Chinese Placement test result from Yes No Confucius Institute by Hanban Course certificate from Yes Yes, but only if Confucius Institute by Hanban Chinese is your 3rd language Business Chinese test Yes Yes, BCT4 or higher CEMS language: BCT3 3rd language: BCT2 HSK (Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi) Yes Yes, HSK4 or higher + CEMS language: HSKK (oral test) HSK3 intermediate or higher 3rd language: HSK2 Czech Státní jazyková zkouška základní Yes Yes z češtiny pro cizince (State examination in Czech for foreigners) Exam CCE (general language) – Yes Yes B2 or higher Danish Studieprøven Yes Yes Prøve i Dansk 3 Yes Yes Dutch Educatief professioneel C1 Yes Yes Professioneel gevorderd B2 Yes Yes Educatief startbekwaam B2 Yes Yes Maatschappelijk formeel B1 Yes Yes, but only -

Fremdsprachenzertifikate in Der Schule

FREMDSPRACHENZERTIFIKATE IN DER SCHULE Handreichung März 2014 Referat 522 Fremdsprachen, Bilingualer Unterricht und Internationale Abschlüsse Redaktion: Henny Rönneper 2 Vorwort Fremdsprachenzertifikate in den Schulen in Nordrhein-Westfalen Sprachen öffnen Türen, diese Botschaft des Europäischen Jahres der Sprachen gilt ganz besonders für junge Menschen. Das Zusammenwachsen Europas und die In- ternationalisierung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft verlangen die Fähigkeit, sich in mehreren Sprachen auszukennen. Fremdsprachenkenntnisse und interkulturelle Er- fahrungen werden in der Ausbildung und im Studium zunehmend vorausgesetzt. Sie bieten die Gewähr dafür, dass Jugendliche die Chancen nutzen können, die ihnen das vereinte Europa für Mobilität, Begegnungen, Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung bietet. Um die fremdsprachliche Bildung in den allgemein- und berufsbildenden Schulen in Nordrhein-Westfalen weiter zu stärken, finden in Nordrhein-Westfalen internationale Zertifikatsprüfungen in vielen Sprachen statt, an denen jährlich mehrere tausend Schülerinnen und Schüler teilnehmen. Sie erwerben internationale Fremdsprachen- zertifikate als Ergänzung zu schulischen Abschlusszeugnissen und zum Europäi- schen Portfolio der Sprachen und erreichen damit eine wichtige Zusatzqualifikation für Berufsausbildungen und Studium im In- und Ausland. Die vorliegende Informationsschrift soll Lernende und Lehrende zu fremdsprachli- chen Zertifikatsprüfungen ermutigen und ihnen angesichts der wachsenden Zahl an- gebotener Zertifikate eine Orientierungshilfe geben. -

ALTE Framework 2019

ALTE Framework 2019 A1 A2 B1 B2 C1 C2 Language Organisation Pre-A1 ALTE Breakthrough ALTE Level 1 ALTE Level 2 ALTE Level 3 ALTE Level 4 ALTE Level 5 Euskararen Gaitasun Agiria (EGA) • Re-audit Nov 2021 Basque Government Eusko Jaurlaritza Basque Euskara Euskararen Gaitasun Agiria (EGA) • Re-audit pending Government of Navarre Gobierno de Navarra Standardised Test in Bulgarian as a Foreign Sofia University St. Language B2 Kliment Ohridski – • Re-audit March 2019 Department for Language Teaching - Bulgarian DLTIS Български език Софийски университет "Св. Климент Охридски" – Департамент за езиково обучение – ДЕО Version date: 05/02/2019 ALTE Framework 2019 A1 A2 B1 B2 C1 C2 Language Organisation Pre-A1 ALTE Breakthrough ALTE Level 1 ALTE Level 2 ALTE Level 3 ALTE Level 4 ALTE Level 5 Nivell superior de català Catalan Generalitat of Catalonia • Audit pending Català Generalitat de Catalunya Charles University in The Czech Language The Czech Language The Czech Language The Czech Language The Czech Language Prague, Institute for Certificate Exam (CCE) Certificate Exam (CCE) Certificate Exam (CCE) Certificate Exam (CCE) Certificate Exam (CCE) Language and A1 A2 B1 B2 C1 Czech Preparatory Studies • Re-audit Jan 2021 • Re-audit Jan 2021 • Re-audit Jan 2021 • Re-audit Jan 2021 • Re-audit Jan 2021 (ILPS) Čeština Univerzita Karlova v Praze, Ústav jazykové a odborné přípravy, (ÚJOP UK) Prøve i Dansk 1 (PD1) Prøve i Dansk 2 (PD2) Prøve i Dansk 3 (PD3) • • • The Ministry for Re-audit Oct 2022 Re-audit Oct 2022 Re-audit Oct 2022 Danish Foreigners and Integration -

Types of Documents Confirming the Knowledge of a Foreign Language by Foreigners

TYPES OF DOCUMENTS CONFIRMING THE KNOWLEDGE OF A FOREIGN LANGUAGE BY FOREIGNERS 1. Diplomas of completion of: 1) studies in the field of foreign languages or applied linguistics; 2) a foreign language teacher training college 3) the National School of Public Administration (KSAP). 2. A document issued abroad confirming a degree or a scientific title – certifies the knowledge of the language of instruction 3. A document confirming the completion of higher or postgraduate studies conducted abroad or in Poland - certifies the knowledge of the language only if the language of instruction was exclusively a foreign language. 4. A document issued abroad that is considered equivalent to the secondary school-leaving examination certificate - certifies the knowledge of the language of instruction 5. International Baccalaureate Diploma. 6. European Baccalaureate Diploma. 7. A certificate of passing a language exam organized by the following Ministries: 1) the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; 2) the ministry serving the minister competent for economic affairs, the Ministry of Cooperation with Foreign Countries, the Ministry of Foreign Trade and the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Marine Economy; 3) the Ministry of National Defense - level 3333, level 4444 according to the STANAG 6001. 8. A certificate confirming the knowledge of a foreign language, issued by the KSAP as a result of linguistic verification proceedings. 9. A certificate issued by the KSAP confirming qualifications to work on high-rank state administration positions. 10. A document confirming -

Relating Language Examinations to the CEFR: a Manual

January 2009 Relating Language Examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR) A Manual Language Policy Division, Strasbourg www.coe.int/lang Contents List of Figures Page iii List of Tables Page v List of Forms Page vii Preface Page ix Chapter 1: The CEFR and the Manual Page 1 Chapter 2: The Linking Process Page 7 Chapter 3: Familiarisation Page 17 Chapter 4: Specification Page 25 Chapter 5: Standardisation Training and Benchmarking Page 35 Chapter 6: Standard Setting Procedures Page 57 Chapter 7: Validation Page 89 References Page 119 Appendix A Forms and Scales for Description and Specification (Ch. 1 & 4) Page 122 A1: Salient Characteristics of CEFR Levels (Ch. 1) Page 123 A2: Forms for Describing the Examination (Ch. 4) Page 126 A3: Specification: Communicative Language Activities (Ch. 4) Page 132 A4: Specification: Communicative Language Competence (Ch. 4) Page 142 A5: Specification: Outcome of the Analysis (Ch. 4) Page 152 Appendix B Content Analysis Grids (Ch.4) B1: CEFR Content Analysis Grid for Listening & Reading Page 153 B2: CEFR Content Analysis Grids for Writing and Speaking Tasks Page 159 Appendix C Forms and Scales for Standardisation & Benchmarking (Ch. 5) Page 181 Reference Supplement: Section A: Summary of the Linking Process Section B: Standard Setting Section C: Classical Test Theory Section D: Qualitative Analysis Methods Section E: Generalisability Theory Section F: Factor Analysis Section G: Item Response Theory Section H: Test Equating i ii List of -

An Overview of the Issues on Incorporating the TOEIC Test Into the University English Curricula in Japan TOEIC テストを大学英語カリキュラムに取り込む問題点について

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE 127 An Overview of the Issues on Incorporating the TOEIC test into the University English Curricula in Japan TOEIC テストを大学英語カリキュラムに取り込む問題点について Junko Takahashi Abstract: The TOEIC test, which was initially developed for measuring general English ability of corporate workers, has come into wide use in educational institutions in Japan including universities, high schools and junior high schools. The present paper overviews how this external test was incorporated into the university English curriculum, and then examines the impact and influence that the test has on the teaching and learning of English in university. Among various uses of the test, two cases of the utilization will be discussed; one case where the test score is used for placement of newly enrolled students, and the other case where the test score is used as requirements for a part or the whole of the English curriculum. The discussion focuses on the content and vocabulary of the test, motivation, and the effectiveness of test preparation, and points out certain difficulties and problems associated with the incorporation of the external test into the university English education. Keywords: TOEIC, university English curriculum, proficiency test, placement test 要約:企業が海外の職場で働く社員の一般的英語力を測定するために開発された TOEIC テストが、大学や中学、高校の学校教育でも採用されるようになった。本稿は、 TOEIC という外部標準テストが大学内に取り込まれるに至る経緯を概観し、テストが 大学の英語教育全般に及ぼす影響および問題点を考察する。大学での TOEIC テストの 利用法は多岐に及ぶが、その中で特にクラス分けテストとしての利用と単位認定や成 績評価にこのテストのスコアを利用する 2 種類の場合を取り上げ、テストの内容・語 彙、動機づけ、受験対策の効果などの観点から、外部標準テストの利用に伴う困難点 を論じる。 キーワード:TOEIC、大学英語教育カリキュラム、実力テスト、クラス分けテスト 1. Background of the TOEIC Test 1. 1 Socio-economic pressure on English education The TOEIC (Test of English for International Communication) test is an English proficiency test for the speakers of English as a second or foreign language developed by the Educational Testing Service (ETS), the same organization which creates the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) test. -

Preliminary Programme

Preliminary programme Language learning, teaching and assessment… … in a globalised economy Investigating the necessary elements to design and implement a communicative test for engineering students: A backwash effect Ada Luisa Arellano Méndez, Mextesol, Mexico The written English Matura exam in Poland: Assessment, policy, and practice Aleksandra Kasztalska, Southern Arkansas University, United States Aleksandra Swatek, Purdue University, United States Validating university entrance test assumptions: Some inconvenient facts Bart Deygers, KU Leuven, Belgium Language assessment in teacher education programmes in Colombia Bozena Lechowska, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colombia Assessment in a globalised economy: A task-based approach to assess the proficiency of Dutch in specific occupational domains Christina Maes, CNaVT, Centre of Language and Education, KU Leuven, Belgium Sarah Smirnow, CNaVT, Centre of Language and Education, KU Leuven, Belgium Lucia Luyten, CNaVT, Centre of Language and Education, KU Leuven, Belgium Testing pre-service teachers’ spoken English proficiency: Design, washback and impact Daniel Xerri, University of Malta, Malta Odette Vassallo, University of Malta, Malta Sarah Grech, University of Malta, Malta Certification of Proficiency in Polish as a foreign language and its influence over the Polish labour market Dominika Bartosik, Jagiellonian University Kraków, Poland Évaluer la compétence à communiquer en français dans l’entreprise Dominique Casanova, CCI Paris Ile-de-France – Centre de langue française,