Studies in Applied Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

Madagascar Location Geography

Madagascar Location Madagascar lies off the east coast of Africa in the Indian Ocean. The Mozambique channel divides the island with the African continent. It is the largest of the Indian Ocean’s many islands, and is the fourth largest island in the world, following Greenland, New Guinea, and Borneo. The land aeria isw about the size of the states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa combined and covers 226,658 square miles. The island is 976 miles long and 335 miles across at it’s widest point, and is shaped like an irregular oval. It has some smaller islands surrounding it, including Nosy Be, eight miles off of the coast in the Bay of Ampasindava in the northwest. Saint-Marie off the east coast and Nosy Be off the west coast are islands large enough to support inhabitants. There are also several tiny uninhabited islands in the Mozambique Channel: Nosy Mitsio, the Radama Islands, Chesterfield Island, and the Barren Islands. Geography This unique country is divided into three regions that run north and south along the length of the island. On the eastern side, along the Indian Ocean, there is a narrow piece of tropical lowlands, consisting mostly of flat plains. It is about 30 miles wide and includes marshes, but is very fertile. The eastern coast is unique in that for almost 1000 miles, it runs in a straight almost uninterrupted line from southwest to northeast. It has many white sand beaches with coral reefs, and the ocean is the roughest on this side of the island, facing out to the Indian Ocean. -

West Africa from Franco CFA to Eco: Economic Issues

ISSN: 2278-3369 International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics Available online at: www.managementjournal.info REVIEW ARTICLE West Africa from Franco CFA to Eco: Economic Issues Palumbo Vincenzo*, Villani Chiara Universita’ di Napoli Federico II Italy. *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Abstract: Born 73 years ago, exactly on December 26, 1945, the day France ratified the Bretton Woods agreements, the CFA franc is the currency adopted by 14 African states and for years the subject of controversy at the local level as well as in France itself. For some months the debate has become international and now this often criticized currency will give way to a new common currency called Eco. Keywords: West Africa, Economic issue, Franco CFA. Article Received: 01 Jan 2021 Revised: 24 Jan 2021 Accepted: 15 Feb. 2021 Introduction First of all, we need to take a big step back in single and independent currency it finally time: It was December 1945 when a decree appears to them as a concrete step in the signed by General Charles de Gaulle actually instituted a currency. Thus was born the direction of real autonomy. But the reality is CFA franc, which at the time when Paris more complex and beyond ideological and ratified the Bretton Woods accords meant political positions there is an objective way in Franco of the French colonies of Africa. which it is possible to approach the issue: economic science. Thus a monetary union was born. The 14 nations that are part of it today are in fact CFA: Economic Technicisms between divided into the Economic and Monetary Advantages and Disadvantages Union of West Africa (UEMOA) and the Substantially, the Economic Technical Economic and Monetary Community of Characteristics on Which the CFA Central Africa (CEMAC). -

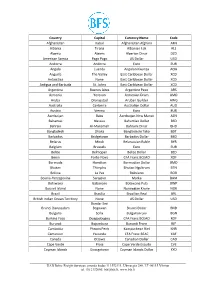

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

The Big Reset: War on Gold and the Financial Endgame

WILL s A system reset seems imminent. The world’s finan- cial system will need to find a new anchor before the year 2020. Since the beginning of the credit s crisis, the US realized the dollar will lose its role em as the world’s reserve currency, and has been planning for a monetary reset. According to Willem Middelkoop, this reset MIDD Willem will be designed to keep the US in the driver’s seat, allowing the new monetary system to include significant roles for other currencies such as the euro and China’s renminbi. s Middelkoop PREPARE FOR THE COMING RESET E In all likelihood gold will be re-introduced as one of the pillars LKOOP of this next phase in the global financial system. The predic- s tion is that gold could be revalued at $ 7,000 per troy ounce. By looking past the American ‘smokescreen’ surrounding gold TWarh on Golde and the dollar long ago, China and Russia have been accumu- lating massive amounts of gold reserves, positioning them- THE selves for a more prominent role in the future to come. The and the reset will come as a shock to many. The Big Reset will help everyone who wants to be fully prepared. Financial illem Middelkoop (1962) is founder of the Commodity BIG Endgame Discovery Fund and a bestsell- s ing author, who has been writing about the world’s financial system since the early 2000s. Between 2001 W RESET and 2008 he was a market commentator for RTL Television in the Netherlands and also BIG appeared on CNBC. -

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name*

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Afghanistan AFA Afghani Albania ALL Lek Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Amer Samoa USD US Dollar Andorra ADP Andorran Peseta Angola AON New Kwanza Anguilla XCD East Caribbean Dollar Antigua Barb XCD East Caribbean Dollar Argentina ARS Argentine Peso Armenia AMD Armeniam Dram Aruba AWG Aruban Guilder Australia AUD Australian Dollar Austria ATS Schilling Azerbaijan AZM Azerbaijanian Manat Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahrain BHD Bahraini Dinar Bangladesh BDT Taka Barbados BBD Barbados Dollar Belarus BYB Belarussian Ruble Belgium BEF Belgian Franc Belize BZD Belize Dollar Benin XOF CFA Franc Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Bhutan BTN Ngultrum Bolivia BOB Boliviano Botswana BWP Pula Br Ind Oc Tr USD US Dollar Br Virgin Is USD US Dollar Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Brunei Darsm BND Brunei Dollar Bulgaria BGN New Lev Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Côte dIvoire XOF CFA Franc Cambodia KHR Riel Cameroon XAF CFA Franc Canada CAD Canadian Dollar Cape Verde CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cayman Is KYD Cayman Islands Dollar Cent Afr Rep XAF CFA Franc Chad XAF CFA Franc Channel Is GBP Pound Sterling Chile CLP Chilean Peso China CNY Yuan Renminbi China, Macao MOP Pataca China,H.Kong HKD Hong Kong Dollar China,Taiwan TWD New Taiwan Dollar Christmas Is AUD Australian Dollar Cocos Is AUD Australian Dollar Colombia COP Colombian Peso Comoros KMF Comoro Franc FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Congo Dem R CDF Franc Congolais Congo Rep XAF CFA Franc Cook Is NZD New Zealand Dollar Costa Rica -

The Franc Zone

The franc zone The franc zone is an economic, monetary and cultural area that is equivalent to none other in the world. It is made up of very diverse states and territories and results from developments and changes in the former French colonial empire. After attaining their independence, most of the newly-created African states decided to remain within a homogenous group characterised by a new institutional framework and a common exchange rate mechanism. Fact Sheet The franc zone is made up of France and 15 African states: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo in West Africa, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon in Central Africa, and the Comoros. The franc zone is a rare example of close institutionalised cooperation between countries from two continents that share a common language and history. The Banque de France has developed close ties with the franc zone central banks, with which it works towards ensuring the smooth functioning of the area’s shared institutions. This Fact Sheet describes the franc zone’s institutional structures and the changes they are undergoing, and brings to the fore the franc zone countries’ determination to forge ahead with regional integration in order to support growth and reduce poverty. The franc zone annual report provides detailed information on the eco- nomic and financial situation of the franc zone. It is published by the Banque de France and available on its website www.banque-france.fr n° 127 April 2002 updated July 2010 Communication Directorate 1. HISTORY OF THE FRANC ZONE 1.1. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 05:25:09AM Via Free Access MADAGASCAR CLIMAT I C DIAGRAMS --.------,..----...--12

Afrika Focus, Vol. 6, Nr. 1, 1990, pp. 88-93 MADAGASCAR 1. Official name: Democratic Republic of Madagascar Repoblica Malagasy 2. Geography: 2.1.Situation: Madagascar is an island in the Indian Ocean east of Tanzania between 12S and 25S, 43.36'E and 47"13'E. 2.2. Total area: 587 041 km. 2.3. Natural regions: the major highlands are situated on a central axis running north-south. 1bere are mountains with altitudes up to 2500 m, volcanic as in Ankaratra and Tsaratanana or crystalline as in Adringitra. The lower areas form a narrow wne close to the coast except for the wide terrace plains in the west and panly in the south. 2.4. Climate: ranges from humid tropical in the east to semi- desert in the southwest. The altitudes temper the hot tropical climate in the mountain regions. The northwest monsoon brings rain to the northwest ofMadagascar, the moisture loaden tradewinds bring heavy rains to the eastern littoral regions. 3. Population: 3.1. Total population: 10.2 min (1985), urban population: 21 %. 3.2. Population density: 17 per km. 3.3. Population growth rate: 3.2% (1980-1985). 3.4. Capital: ANTANANARIVO, 663.000 inh. (1985). 3.5. Languages: Malagasy, French (official), English. 89 Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 05:25:09AM via free access MADAGASCAR CLIMAT I C DIAGRAMS --.----------,..----...--12. tlF ~11 I I I 15• " ·'"I I" JI"'"'. I "· 3 2 7 2 "'"' YOHE MAR AMBODll'OTOTRA ANANAlllY 20• M A U N G A ANKAZOAIO BETIOKY SUD 80m m ', ;' { \ / l ",'/ I 2 s• T U L E A II Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 05:25:09AM via free access 3.6.Religion: 40% Christians (1/2 Roman Catholics), traditional beliefs (57% }, Muslims. -

Em Fim De Mês Other Informative Exchange Rates - End-Of-Month Rate

Taxas de Câmbio informativas de outras moedas - em fim de mês Other Informative Exchange Rates - end-of-month rate Banco de Portugal (a) X de moeda estrangeira por 1 Euro (preço médio) X foreign exchange units per 1 euro (mid-rates) EUROPA/EUROPE Setembro/September PAÍS/COUNTRY MOEDA/CURRENCY 2009 BIELORRÚSSIA/BELARUS Rublo bielorrusso/Belarusian rouble BYR 4.044,40 SÉRVIA/SERBIA Dinar sérvio (b)/Dinar RSD 93,2759 GIBRALTAR/GIBRALTAR Libra de Gibraltar/Gibraltar pound GIP 0,9093 UCRÂNIA/UKRAINE Hryvnia da Ucrânia/Hryvnia UAH 12,0951 ÁFRICA/AFRICA Setembro/September PAÍS/COUNTRY MOEDA/CURRENCY 2009 ANGOLA/ANGOLA Kwanza (c) /Kwanza (c) AOA 113,3285 BOTSUANA/BOTSWANA Pula de Botsuana/Pula BWP 9,6494 CONGO (Rep.Dem.)/CONGO (Dem. Rep.) Franco congolês (d) /Congolese Franc (d) CDF 1.212,9960 ARGÉLIA/ALGERIA Dinar argelino/Algerian dinar DZD 106,2224 EGIPTO/EGYPTO Libra egípcia/Egyptian pound EGP 8,0566 ETIÓPIA/ETHIOPIA Birr etíope/Ethiopian birr ETB 18,4429 GANA/GHANA Cedi do Gana (e)/Cedi (e) GHS 2,1218 GUINÉ/GUINEA Franco guineense/Guinean franc GNF 7.358,11 QUÉNIA/KENYA Xelim queniano/Kenyan shilling KES 109,1636 LIBÉRIA/LIBERIA Dólar liberiano/Liberian dollar LRD 95,1795 LÍBIA/LIBYA Dinar líbio/Libyan dinar LYD 1,77912 MARROCOS/MOROCCO Dirham marroquino/Moroccan dirham MAD 11,3769 MADAGÁSCAR/MADAGASCAR Ariary Malgaxe (f)/Malagasy Ariary (f) MGA 2.939,58 MAURITÂNIA/MAURITANIA Ouguiya mauritana/Mauritanian ouguiya MRO 382,182 MAURÍCIA/MAURITIUS Rupia mauriciana/Mauritian rupee MUR 44,6612 MALAWI/MALAWI Kwacha do Malawi/Malawi kwacha MWK 206,8324 MOÇAMBIQUE/MOZAMBIQUE Metical de Moçambique (g)/Metical (g) MZN 42,16 NAMÍBIA/NAMIBIA Dólar namibiano/Nabimian dollar NAD 10,8984 NIGÉRIA/NIGERIA Naira da Nigéria/Nigerian naira NGN 216,2771 SUDÃO/SUDAN Libra Sudanesa (h)/Sudanese Pound (h) SDG 3,3969 SERRA LEOA/SIERRA LEONE Leona da Serra Leoa/Leone SLL 5.347,62 SOMÁLIA/SOMALIA Xelim somaliano/Somali shilling SOS 2.123,24 S. -

Currencies of the World

The World Trade Press Guide to Currencies of the World Currency, Sub-Currency & Symbol Tables by Country, Currency, ISO Alpha Code, and ISO Numeric Code € € € € ¥ ¥ ¥ ¥ $ $ $ $ £ £ £ £ Professional Industry Report 2 World Trade Press Currencies and Sub-Currencies Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies of the World of the World World Trade Press Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s 800 Lindberg Lane, Suite 190 Petaluma, California 94952 USA Tel: +1 (707) 778-1124 x 3 Introduction . 3 Fax: +1 (707) 778-1329 Currencies of the World www.WorldTradePress.com BY COUNTRY . 4 [email protected] Currencies of the World Copyright Notice BY CURRENCY . 12 World Trade Press Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies Currencies of the World of the World © Copyright 2000-2008 by World Trade Press. BY ISO ALPHA CODE . 20 All Rights Reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the express written permission of the Currencies of the World copyright holder is unlawful. Requests for permissions and/or BY ISO NUMERIC CODE . 28 translation or electronic rights should be addressed to “Pub- lisher” at the above address. Additional Copyright Notice(s) All illustrations in this guide were custom developed by, and are proprietary to, World Trade Press. World Trade Press Web URLs www.WorldTradePress.com (main Website: world-class books, maps, reports, and e-con- tent for international trade and logistics) www.BestCountryReports.com (world’s most comprehensive downloadable reports on cul- ture, communications, travel, business, trade, marketing, -

Swift Currency Codes

Balance of Payments Reporting System 1 SECTION C.4 SWIFT CURRENCY AND COUNTRY CODES COUNTRY CURRENCY CURRENCY COUNTRY CODE CODE Afghanistan Afghani AFA AF Albania Lek ALL AL Algeria Algerian Dinar DZD DZ American Samoa US Dollar USD AS Andorra Andorran Peseta ADP AD Andorra Spanish Peseta ESP AD Andorra French Franc FRF AD Angola New Kwanza AON AO Angola Kwanza Reajustado AOR AO Anguilla East Carribean Dollar XCD AI Antigua and Barbuda East Carribean Dollar XCD AG Argentina Argentine Peso ARS AR Armenia Armenian Dram AMD AM Aruba Aruban Guilder AWG AW Australia Australian Dollar AUD AU Austria Schilling ATS AT Austria Euro EUR AT Azerbaijan Azerbaijanian Manat AZM AZ Bahamas Bahamian Dollar BSD BS Bahrain Bahraini Dinar BHD BH Bangladesh Taka BDT BD Barbados Barbados Dollar BBD BB Belarus Belarussian Ruble BYB BY Belarus Belarussian Ruble (new) BYR BY Belgium Belgian Franc BEF BE Belgium Euro EUR BE Belize Belize Dollar BZD BZ Benin CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BJ Bermuda Bermudian Dollar BMD BM Bhutan Ngultrum BTN BT Bhutan Indian Rupee INR BT Bolivia Boliviano BOB BO Bolivia Mvdol BOV BO Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Marks BAM BA Botswana Pula BWP BW Bouvet Island Norwegian Krone NOK BV Brazil Brazilian Real BRL BR British Indian Ocean US Dollar USD IO Territory Brunei Darussalam Burnei Dollar BND BN Bulgaria Lev BGL BG Bulgaria Bulgarian Lev BGN BG Burkina Faso CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BF Burundi Burundi Franc BIF BI Operations manual (Customer transaction reporting) 1 November 2001 Balance of Payments Reporting System 2 SECTION C.4 COUNTRY -

Metadata on the Exchange Rate Statistics

Metadata on the Exchange rate statistics Last updated 26 February 2021 Afghanistan Capital Kabul Central bank Da Afghanistan Bank Central bank's website http://www.centralbank.gov.af/ Currency Afghani ISO currency code AFN Subunits 100 puls Currency circulation Afghanistan Legacy currency Afghani Legacy currency's ISO currency AFA code Conversion rate 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new); with effect from 7 October 2002 Currency history 7 October 2002: Introduction of the new afghani (AFN); conversion rate: 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new) IMF membership Since 14 July 1955 Exchange rate arrangement 22 March 1963 - 1973: Pegged to the US dollar according to the IMF 1973 - 1981: Independently floating classification (as of end-April 1981 - 31 December 2001: Pegged to the US dollar 2019) 1 January 2002 - 29 April 2008: Managed floating with no predetermined path for the exchange rate 30 April 2008 - 5 September 2010: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 6 September 2010 - 31 March 2011: Stabilised arrangement (exchange rate within a narrow band without any political obligation) 1 April 2011 - 4 April 2017: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 5 April 2017 - 3 May 2018: Crawl-like arrangement (moving central rate with an annual minimum rate of change) Since 4 May 2018: Other managed arrangement Time series BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.M.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A01