5 Steps to Selecting the Right RF Power Amplifier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Basic Concepts in RF Design

Chapter 2 Basic Concepts in RF Design 1 Sections to be covered • 2.1 General Considerations • 2.2 Effects of Nonlinearity • 2.3 Noise • 2.4 Sensitivity and Dynamic Range • 2.5 Passive Impedance Transformation 2 Chapter Outline Nonlinearity Noise Impedance Harmonic Distortion Transformation Compression Noise Spectrum Intermodulation Device Noise Series-Parallel Noise in Circuits Conversion Matching Networks 3 The Big Picture: Generic RF Transceiver Overall transceiver Signals are upconverted/downconverted at TX/RX, by an oscillator controlled by a Frequency Synthesizer. 4 General Considerations: Units in RF Design Voltage gain: rms value Power gain: These two quantities are equal (in dB) only if the input and output impedance are equal. Example: an amplifier having an input resistance of R0 (e.g., 50 Ω) and driving a load resistance of R0 : 5 where Vout and Vin are rms value. General Considerations: Units in RF Design “dBm” The absolute signal levels are often expressed in dBm (not in watts or volts); Used for power quantities, the unit dBm refers to “dB’s above 1mW”. To express the signal power, Psig, in dBm, we write 6 Example of Units in RF An amplifier senses a sinusoidal signal and delivers a power of 0 dBm to a load resistance of 50 Ω. Determine the peak-to-peak voltage swing across the load. Solution: a sinusoid signal having a peak-to-peak amplitude of Vpp an rms value of Vpp/(2√2), 0dBm is equivalent to 1mW, where RL= 50 Ω thus, 7 Example of Units in RF A GSM receiver senses a narrowband (modulated) signal having a level of -100 dBm. -

RF CMOS Power Amplifiers: Theory, Design and Implementation the KLUWER INTERNATIONAL SERIES in ENGINEERING and COMPUTER SCIENCE

RF CMOS Power Amplifiers: Theory, Design and Implementation THE KLUWER INTERNATIONAL SERIES IN ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE ANALOG CIRCUITS AND SIGNAL PROCESSING Consulting Editor: Mohammed Ismail. Ohio State University Related Titles: POWER TRADE-OFFS AND LOW POWER IN ANALOG CMOS ICS M. Sanduleanu, van Tuijl ISBN: 0-7923-7643-9 RF CMOS POWER AMPLIFIERS: THEORY, DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION M.Hella, M.Ismail ISBN: 0-7923-7628-5 WIRELESS BUILDING BLOCKS J.Janssens, M. Steyaert ISBN: 0-7923-7637-4 CODING APPROACHES TO FAULT TOLERANCE IN COMBINATION AND DYNAMIC SYSTEMS C. Hadjicostis ISBN: 0-7923-7624-2 DATA CONVERTERS FOR WIRELESS STANDARDS C. Shi, M. Ismail ISBN: 0-7923-7623-4 STREAM PROCESSOR ARCHITECTURE S. Rixner ISBN: 0-7923-7545-9 LOGIC SYNTHESIS AND VERIFICATION S. Hassoun, T. Sasao ISBN: 0-7923-7606-4 VERILOG-2001-A GUIDE TO THE NEW FEATURES OF THE VERILOG HARDWARE DESCRIPTION LANGUAGE S. Sutherland ISBN: 0-7923-7568-8 IMAGE COMPRESSION FUNDAMENTALS, STANDARDS AND PRACTICE D. Taubman, M. Marcellin ISBN: 0-7923-7519-X ERROR CODING FOR ENGINEERS A.Houghton ISBN: 0-7923-7522-X MODELING AND SIMULATION ENVIRONMENT FOR SATELLITE AND TERRESTRIAL COMMUNICATION NETWORKS A.Ince ISBN: 0-7923-7547-5 MULT-FRAME MOTION-COMPENSATED PREDICTION FOR VIDEO TRANSMISSION T. Wiegand, B. Girod ISBN: 0-7923-7497- 5 SUPER - RESOLUTION IMAGING S. Chaudhuri ISBN: 0-7923-7471-1 AUTOMATIC CALIBRATION OF MODULATED FREQUENCY SYNTHESIZERS D. McMahill ISBN: 0-7923-7589-0 MODEL ENGINEERING IN MIXED-SIGNAL CIRCUIT DESIGN S. Huss ISBN: 0-7923-7598-X CONTINUOUS-TIME SIGMA-DELTA MODULATION FOR A/D CONVERSION IN RADIO RECEIVERS L. -

Wideband Automatic Gain Control Design in 130 Nm CMOS Process for Wireless Receiver Applications

Wideband Automatic Gain Control Design in 130 nm CMOS Process for Wireless Receiver Applications A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering By Joseph Benito Strzelecki, B.S. Wright State University, 2013 2015 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL _August 19, 2015_______ I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Joseph Benito Strzelecki ENTITLED Wideband Automatic Gain Control Design in 130 nm CMOS Process for Wireless Receiver Applications BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science in Engineering. ___________________________________ Saiyu Ren, Ph.D. Thesis Director ___________________________________ Brian D. Rigling, Ph.D. Department Chair Committee on Final Examination ________________________________ Saiyu Ren, Ph.D. ________________________________ Raymond E. Siferd, Ph.D. ________________________________ John M. Emmert, Ph.D. ________________________________ Arnab K. Shaw, Ph.D. ________________________________ Robert E. W. Fyffe, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School Abstract Strzelecki, Joseph Benito, M.S.Egr, Department of Electrical Engineering, Wright State University, 2015. “Wideband Automatic Gain Control Design in 130 nm CMOS Process for Wireless Receiver Applications” An analog automatic gain control circuit (AGC) and mixer were implemented in 130 nm CMOS technology. The proposed AGC was intended for implementation into a wireless receiver chain. Design specifications required a 60 dB tuning range on the output of the AGC, a settling time within several microseconds, and minimum circuit complexity to reduce area usage and power consumption. Desired AGC functionality was achieved through the use of four nonlinear variable gain amplifiers (VGAs) and a single LC filter in the forward path of the circuit and a control loop containing an RMS power detector, a multistage comparator, and a charging capacitor. -

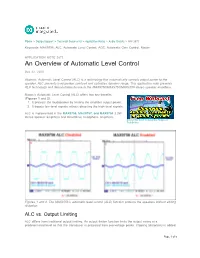

An Overview of Automatic Level Control

Maxim > Design Support > Technical Documents > Application Notes > Audio Circuits > APP 3673 Keywords: MAX9756, ALC, Automatic Level Control, AGC, Automatic Gain Control, Maxim APPLICATION NOTE 3673 An Overview of Automatic Level Control Dec 22, 2005 Abstract: Automatic Level Control (ALC) is a technology that automatically controls output power to the speaker. ALC prevents loudspeaker overload and optimizes dynamic range. This application note presents ALC technology and demonstrates its use in the MAX9756/MAX9757/MAX9758 stereo speaker amplifiers. Maxim's Automatic Level Control (ALC) offers two key benefits (Figures 1 and 2). 1. It protects the loudspeaker by limiting the amplifier output power. 2. It boosts low-level signals without distorting the high-level signals. ALC is implemented in the MAX9756, MAX9757, and MAX9758 2.3W stereo speaker amplifiers and DirectDrive headphone amplifiers. Attend this brief webcast by Maxim on TechOnline Figures 1 and 2. The MAX9756's automatic level control (ALC) function protects the speakers without adding distortion. ALC vs. Output Limiting ALC differs from traditional output limiting. An output-limiter function limits the output swing at a predetermined level so that the transducer is protected from overvoltage peaks. Clipping (distortion) is added Page 1 of 5 at the output signal as a result (Figure 3). An ALC function, however, reduces the gain so that the transducer is protected. No distortion is added (Figure 4). Figure 3. The output limiter clips the output signal in overvoltage conditions and, thus, produces audible distortion. Figure 4. The MAX9756's ALC reduces the amplifier gain in overvoltage conditions so that no distortion is added to the output signal. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Wideband Reconfigurable Blocker Tolerant Receiver for Cognitive Radio Applications a Disser

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Wideband Reconfigurable Blocker Tolerant Receiver for Cognitive Radio Applications A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering by Qaiser Nehal 2018 c Copyright by Qaiser Nehal 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Wideband Reconfigurable Blocker Tolerant Receiver for Cognitive Radio Applications by Qaiser Nehal Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Asad A. Abidi, Chair Cognitive radios (CRs) use \white spaces" in spectrum for communication. This requires front-end circuits that are highly linear when the white space is adjacent to a strong blocker. For example, in the TV spectrum (54 MHz-862 MHz) broadcast transmissions are the block- ers. This work describes the design of a wideband blocker tolerant receiver. First EKV based MOSFET model is used to analyze RF transconductor distortion. Expressions for its IIP3 and P1dB are also given. Derivative superposition based linearization scheme for the RF transconductor is also explained. Second mixer switch nonlinearity is analyzed using EKV. Simple expressions for receiver IIP3 and P1dB are given that provide design insights for linearity optimization. Low phase noise LO design is also described to lower receiver noise figure in the presence of large blockers. Finally, transimpedance amplifier (TIA) large-signal operation is studied using EKV. It is shown that source follower inverter-based TIA transconductor results in higher receiver P1dB. A prototype receiver based on these ideas was designed in 16nm FinFET CMOS. Mea- sured results show that receiver can operate from 100 MHz to 6 GHz and can tolerate up to +12 dBm blockers. -

Gan Essentials™

APPLICATION NOTE AN-010 GaN Essentials™ AN-010: GaN for LDMOS Users NITRONEX CORPORATION 1 JUNE 2008 APPLICATION NOTE AN-010 GaN Essentials: GaN for LDMOS Users 1. Table of Contents 1. TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................................... 2 2. ABSTRACT......................................................................................................................................................... 3 IMPEDANCE PROFILES.......................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. INPUT IMPEDANCE .................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2. OUTPUT IMPEDANCE ................................................................................................................................ 4 3. STABILITY ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. CAPACITANCE VS. VOLTAGE ................................................................................................................... 6 4.1. TYPICAL CAPACITANCE -VOLTAGE (CV) CHARACTERISTICS ................................................................ 6 4.2. OUTPUT CAPACITANCE COMPARISON BETWEEN GAN AND LDMOS .................................................. 7 5. BIAS CIRCUITS................................................................................................................................................ -

Replacing the Automatic Gain Control Loop in a Mobile, Digital TV Broadcast Receiver by a Software Based Solution

Replacing the automatic gain control loop in a mobile, digital TV broadcast receiver by a software based solution diploma thesis Patrick Boettcher Technische Fachhochschule Wildau Fachbereich Betriebswirtschaft/Wirtschaftsinformatik Date: 09.03.2008 Erstbetreuer: Prof. Dr. Christian Müller Zweitbetreuer: Prof. Dr. Bernd Eylert ii A part of this diploma thesis is not available until April 2010, because it is protected by a lock flag. The complete work can and will be made available by that time. The parts affected are – Chapter 4, – Chapter 5, – Appendix C and – Appendix D. If by that time you cannot find the complete work anywhere, please contact the author. iii Danksagung An dieser Stelle möchte ich all jenen danken, die durch ihre fachliche und persönliche Unterstützung zum Gelingen dieser Diplomarbeit beigetragen haben. Besonderer Dank gebührt meiner Lebenspartnerin Ariane und meinen Eltern, die mir dieses Studium durch ihre Unterstützung ermöglicht haben und mir fortwährend Vorbild und Ansporn waren. Weiterhin bedanke ich mich bei Professor Dr. Christian Müller und Professor Dr. Bernd Eylert für die Betreuung dieser Diplomarbeit. Großer Dank gilt ebenfalls meinen Kollegen bei DiBcom S.A., die mir die Möglichkeit gaben, diese Arbeit zu verfassen und mich technich sehr stark unterstützten. Vor allem möchte ich mich in diesem Zusammenhang bei Jean-Philippe Sibers bedanken, der mir immer mit einer Inspriration zur Seite stand. Gleiches gilt für das „Physical Layer Software Team“: Luc Banda, Frédéric Tarral und Vincent Recrosio. Acknowledgment I want to use this opportunity to thank everyone who supported me personally and professionally to create this diploma thesis. Special thanks appertain to my partner Ariane and my parents, who supported me during my studies and who continuously guided and motivated me. -

Next Topic: NOISE

ECE145A/ECE218A Performance Limitations of Amplifiers 1. Distortion in Nonlinear Systems The upper limit of useful operation is limited by distortion. All analog systems and components of systems (amplifiers and mixers for example) become nonlinear when driven at large signal levels. The nonlinearity distorts the desired signal. This distortion exhibits itself in several ways: 1. Gain compression or expansion (sometimes called AM – AM distortion) 2. Phase distortion (sometimes called AM – PM distortion) 3. Unwanted frequencies (spurious outputs or spurs) in the output spectrum. For a single input, this appears at harmonic frequencies, creating harmonic distortion or HD. With multiple input signals, in-band distortion is created, called intermodulation distortion or IMD. When these spurs interfere with the desired signal, the S/N ratio or SINAD (Signal to noise plus distortion ratio) is degraded. Gain Compression. The nonlinear transfer characteristic of the component shows up in the grossest sense when the gain is no longer constant with input power. That is, if Pout is no longer linearly related to Pin, then the device is clearly nonlinear and distortion can be expected. Pout Pin P1dB, the input power required to compress the gain by 1 dB, is often used as a simple to measure index of gain compression. An amplifier with 1 dB of gain compression will generate severe distortion. Distortion generation in amplifiers can be understood by modeling the amplifier’s transfer characteristic with a simple power series function: 3 VaVaVout=−13 in in Of course, in a real amplifier, there may be terms of all orders present, but this simple cubic nonlinearity is easy to visualize. -

Bias Circuits for RF Devices

Bias Circuits for RF Devices Iulian Rosu, YO3DAC / VA3IUL, http://www.qsl.net/va3iul A lot of RF schematics mention: “bias circuit not shown”; when actually one of the most critical yet often overlooked aspects in any RF circuit design is the bias network. The bias network determines the amplifier performance over temperature as well as RF drive. The DC bias condition of the RF transistors is usually established independently of the RF design. Power efficiency, stability, noise, thermal runway, and ease to use are the main concerns when selecting a bias configuration. A transistor amplifier must possess a DC biasing circuit for a couple of reasons. • We would require two separate voltage supplies to furnish the desired class of bias for both the emitter-collector and the emitter-base voltages. • This is in fact still done in certain applications, but biasing was invented so that these separate voltages could be obtained from but a single supply. • Transistors are remarkably temperature sensitive, inviting a condition called thermal runaway. Thermal runaway will rapidly destroy a bipolar transistor, as collector current quickly and uncontrollably increases to damaging levels as the temperature rises, unless the amplifier is temperature stabilized to nullify this effect. Amplifier Bias Classes of Operation Special classes of amplifier bias levels are utilized to achieve different objectives, each with its own distinct advantages and disadvantages. The most prevalent classes of bias operation are Class A, AB, B, and C. All of these classes use circuit components to bias the transistor at a different DC operating current, or “ICQ”. When a BJT does not have an A.C. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO CMOS RF Power Amplifier Design Approaches for Wireless Communications a Dissertation Submitt

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO CMOS RF Power Amplifier Design Approaches for Wireless Communications A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering (Electronic Circuits and Systems) by Sataporn Pornpromlikit Committee in charge: Professor Peter M. Asbeck, Chair Professor Prabhakar R. Bandaru Professor Andrew C. Kummel Professor Lawrence E. Larson Professor Paul K.L. Yu 2010 Copyright Sataporn Pornpromlikit, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Sataporn Pornpromlikit is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on micro- film and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION To my family. iv EPIGRAPH ”Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school.” — Albert Einstein v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page................................... iii Dedication...................................... iv Epigraph.......................................v Table of Contents.................................. vi List of Figures.................................... viii List of Tables.................................... xi Acknowledgements................................. xii Vita......................................... xiv Abstract of the Dissertation............................. xv Chapter 1 Introduction.............................1 1.1 CMOS Technology and Scaling...............2 1.2 Toward Fully-Integrated CMOS Transceivers........4 1.3 Power Amplifier Design...................5 -

Large Signal RF Power Transmission Characterization of Ingap HBT for RF Power Amplifiers

Vol. 31, No. 1 Journal of Semiconductors January 2010 Large signal RF power transmission characterization of InGaP HBT for RF power amplifiers Zhao Lixin(赵立新), Jin Zhi(金智), and Liu Xinyu(刘新宇) (Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China) Abstract: The large signal RF power transmission characteristics of an advanced InGaP HBT in an RF power amplifier are investigated and analyzed experimentally. The realistic RF powers reflected by the transistor, transmitted from the transistor and reflected by the load are investigated at small signal and large signal levels. The RF power multiple frequency components at the input and output ports are investigated at small signal and large signal levels, including their effects on RF power gain compression and nonlinearity. The results show that the RF power reflections are different between the output and input ports. At the input port the reflected power is not always proportional to input power level; at large power levels the reflected power becomes more serious than that at small signal levels, and there is a knee point at large power levels. The results also show the effects of the power multiple frequency components on RF amplification. Key words: large signal characteristics; InGaP HBT; nonlinearity DOI: 10.1088/1674-4926/31/1/014001 PACC: 7280E; 7360L 1. Introduction nonlinear vector network analyzer systemŒ9; 10, and for maxi- mum output power at initial bias conditions of VCE = 3.61 V, Advanced indium gallium phosphide heterojunction bipo- IC = 53.7 mA, VBE = 1.28 V, IB = 0.71 mA. lar transistors (InGaP HBTs) are key components in RF power With the injection of a sinusoidal RF signal and increas- Œ1 3 amplifiers in radar and communication systems . -

50V RF LDMOS an Ideal RF Power Technology for ISM, Broadcast and Commercial Aerospace Applications Freescale.Com/Rfpower I

White Paper 50V RF LDMOS An ideal RF power technology for ISM, broadcast and commercial aerospace applications freescale.com/RFpower I. INTRODUCTION RF laterally diffused MOS (LDMOS) is currently the dominant device technology used in high-power RF power amplifier (PA) applications for frequencies ranging from 1 MHz to greater than 3.5 GHz. Beginning in the early 1990s, LDMOS has gained wide acceptance for cellular infrastructure PA applications, and now is the dominant RF power device technology for cellular infrastructure. This device technology offered significant advantages over the previous incumbent device technology, the silicon bipolar transistor, providing superior linearity, efficiency, gain and lower cost packaging options. LDMOS technology has continued to evolve to meet the ever more demanding requirements of the cellular infrastructure market, achieving higher levels of efficiency, gain, power and operational frequency[1-8]. The LDMOS device structure is highly flexible. While the cellular infrastructure market has standardized on 28–32V operation, several years ago Freescale developed 50V processes for applications outside of cellular infrastructure. These 50V devices are targeted for use in a wide variety of applications where high power density is a key differentiator and include industrial, scientific, medical (ISM), broadcast and commercial aerospace applications. Many of the same attributes that led to the displacement of bipolar transistors from the cellular infrastructure market in the early 1990s are equally valued in the broad RF power market: high power, gain, efficiency and linearity, low cost and outstanding reliability. In addition, the RF power market demands the very high RF ruggedness that LDMOS can deliver. The enhanced ruggedness LDMOS devices available from Freescale can displace not only bipolar devices but VMOS and vacuum tube devices that are still used in some ISM, broadcast and commercial aerospace applications.