1999-08-10 the Privitisation of New Zealand Rail Part 1: Assessment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2001/02 Annual Plan Vol. I Submissions

2001/02 Annual Plan Vol. I Submissions 16 1 Annual Plan Submissions Note: Those submitters identified in bold type have expressed a desire to be heard in support of their submissions. 1. Norm Morgan Acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick start funding, Water integration, effectiveness of submission process 2. Steve Ritchie Bus service for Robson Street and McManaway Grove , Stokes Valley 3. Nicola Harvey Acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick start funding, Water integration, Marine conservation project for Lyall Bay 4. Alan Waller Rates increases, upgrade to Petone Railway Station 5. John Davis Acquisition of TranzMetro, Water integration, MMP for local government, Emergency management 6. Wellington City Council Floodplain management funding policy 7. Kapiti Coast Grey Power Annual Plan presentation, acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick Assn Inc start funding, rates, operating expenditure, financial management, land management, Parks and Forests, Investment in democracy, 8. John Mcalister Acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick Start funding, Water integration, water supply in the Wairarapa 9. Hutt 2000 Limited Installation of security cameras in Bunny Street Lower 16 Hutt 10. Walk Wellington Inclusion of walking in Regional Land Transport Strategy 11. Hugh Barr Acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick Start funding, Water integration, public access to Water collection areas 2 12. Porirua City Council Bulk Water levy, Transparency of Transport rate, support for Friends of Maara Roa, environmental management and Biodiversity 13. Keep Otaki Beautiful Otaki Bus Shelter 14. Barney Scully Cobham Drive Waterfront/Foreshore 15. Upper Hutt City Council Acquisition of TranzMetro, Water Integration, Hutt River Floodplain Management 16. Wairarapa Green Acquisition of TransMetro, Rick start funding, Issues Network environmental education, rail services, biodiversity 17. -

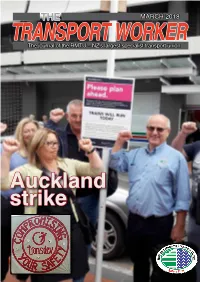

Auckland Strike

THE MARCH 2018 TRANSPORThe journal of the RMTU – NZ'sT largest WORKER specialist transport union Auckland strike 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 1 • march 2018 "On page 14 there is reference to Saida Abad, WHOLE BODY VIBRATION the first female loco 7 engineer in Morocco. I found this billboard with her very moving quote whilst in London recently." Tana Umaga lends a hand to campaign to overcome WBV among LEs. Wayne Butson 10 HISTORIC FIRST General secretary RMTU The entire KiwiRail board made an historic first visit to Hutt workshops Is this the year the recently. MORROCAN CONFERENCE dog bites back? 14 ELCOME to the first issue ofThe Transport Worker magazine for 2018 which, as always, is packed full of just some of the things that your RMTU Union does in the course of its organising for members. delegate Last year ended with a change of Government which should Christine prove to be good news for RMTU members as the governing partners and their sup- Fisiihoi trav- portW partners all have policies which are strongly supportive of rail, ports and the elled all the transport logistics sectors. way to According to the Chinese calendar, 2018 is the year of the dog. However, in my Marrakech view, 2018 is going to be a year of considerable change for RMTU members. We have and was seen Transdev Auckland alter from being a reasonable employer who we have been blown away! doing business with since 2002 to one where dealing with most items has become combative and confrontational. Transdev Wellington is an employer with much less of a working history but we COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Auckland RMTU were able to work with them on the lead up to them taking over the Wellington members pledging solidarity outside Britomart Metro contract and yet, from almost the get go after they took over the running of Place. -

Report 07-101 Express Freight Train 736, Derailment, 309.643 Km, Near

Report 07-101 express freight Train 736, derailment, 5 January 2007 309.643 km, near Vernon The Transport Accident Investigation Commission is an independent Crown entity established to determine the circumstances and causes of accidents and incidents with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Accordingly it is inappropriate that reports should be used to assign fault or blame or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose. The Commission may make recommendations to improve transport safety. The cost of implementing any recommendation must always be balanced against its benefits. Such analysis is a matter for the regulator and the industry. These reports may be reprinted in whole or in part without charge, providing acknowledgement is made to the Transport Accident Investigation Commission. Report 07-101 express freight Train 736 derailment 309.643 km, near Vernon 5 January 2007 Abstract On Friday 5 January 2007, at about 2200, the leading bogie of UK6765, the rear wagon on Christchurch to Picton express freight Train 736, derailed at 309.643 kilometres (km) on the Main North Line. The derailed wagon was dragged a further 3.5 km until it struck the south end main line points at Vernon, derailing the wagon immediately in front. The derailed wagons were pulled another kilometre before the locomotive engineer became aware of the derailed wagons and brought the train to a stop. There were no injuries. A safety issue identified was the current track and mechanical tolerance standards. In view of the safety actions since taken by Toll NZ Consolidated Limited and Ontrack in response to safety recommendations made following similar investigations by the Commission, no further safety recommendations were made. -

Evaluation of Occupational Noise Exposure Levels on the Wellington Suburban Tranz Metro Rail Service

Evaluation of occupational noise exposure levels on the Wellington Suburban Tranz Metro Rail Service 1 Ka’isa Beech and 2 Stuart J McLaren 1 Advanced student at Massey University and Wellington Suburban On-board Staff Member, KiwiRail, Wellington 2 School of Public Health, Massey University, Wellington 2 Email: [email protected] Abstract An occupational noise evaluation study was carried out by Massey University students on locomotive engineers and on-board staff on the two main train sets operating on the Wellington Rail Suburban Network. All measurement results conducted as part of the study show full compliance with the criteria for workplace noise exposure prescribed within the Health and Safety in Employment Regulations 1995. The health and safety noise criterion level permits a maximum dose of 100% which is equivalent to 85 dB LAeq for a normalised 8 hour working day. The highest measured sound exposure was 13% of the total permitted exposure. All occupational noise measurements were observed and written accounts were taken by the three person investigation team. Observations revealed atypical behaviour of one participant which likely compromised one set of readings. This atypical result was removed from the analysis and therefore did not alter the study conclusions. Regardless, such observed behaviour from the study team, reinforces the value of observed real time field monitoring during collection of data. Original peer-reviewed student paper 1. Introduction and purpose of About Ka’isa Beech assessment Age 23, is training to be a The Tranz Metro Rail Passenger Service is operated by Train Traffic Controller KiwiRail and funded by the Greater Wellington Regional with KiwiRail. -

Activist #10, 2009

Rail & Maritime Transport Union Volume ISSUE # 101010 Published Regularly - ISSN 1178-7392 (Print & Online) 1 May 2009 LATEST STATS – UNEMPLOYMENT SHAREHOLDERS ELIGIBLE FOR BENEFIT COMPENSATION FROM TRANZ RAIL Latest statistics released shows that at the CASE end of March 2009, 37,000 working aged A list of the shareholders who are eligible for people (aged 18-64 years) were receiving compensation from the Tranz Rail insider is an Unemployment Benefit. Over the year available from the following Securities to March 2009, the number of recipients of Commission of NZ website link; an Unemployment Benefit increased by 18,000, or 95 percent. The link to the info http://www.seccom.govt.nz/tranz-rail-share- sheet is; refund.shtml#K http://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/abou Shareholders on this list can contact Geoff t-msd-and-our- work/newsroom/factsheets/benefit/2009 Brown on (04) 471 8295 or email /fact-sheet-ub-09-mar-31.doc [email protected] for information about how to claim their compensation. MAY DAY Claimants will need to verify their identity and shareholding details. They should May Day is celebrated and recognized as contact the Commission no later than 24 July the International Workers’ day, chosen over 2009 so that compensation can be paid. 100 years ago to commemorate the struggles and gains of workers and the labour PORTS FORUM movement. Most notable An interesting and reasons to celebrate are challenging programme the 8-hour day, is in store for delegates Saturday as part of the attending the 2009 weekend, improved National Ports Forum in working conditions and Wellington on 5 & 6 child labor laws. -

Annual Integrated Report 2019 Welcome – Tēnā Koutou

F.18A KIWIRAIL’S EVOLUTION ANNUAL INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 WELCOME – TĒNĀ KOUTOU Rail has a long and proud history in reservation and tracking system. Those services contribute to our New Zealand, stretching back more We will also be replacing aging purpose of building a better than 150 years. The financial year to locomotives and wagons and improve New Zealand through stronger 30 June 2019 (FY19) has seen the our major maintenance depots at Hutt connections. Government renew that commitment and Waltham. It will also be used to We do this by putting the customer at to rail, laying the foundations for us to progress the procurement of two new, the centre of everything we do, and our play the role we should in delivering for rail-enabled ferries that will replace workers strive every day to meet their the country. Interislander’s aging Aratere, Kaitaki, needs. In the 2019 Budget, the Government and Kaiarahi ferries. allocated $741 million through Vote Our workforce, spread throughout That outstanding level of investment Transport over the next two years and New Zealand, reflects the nation. It made a further $300 million available is a clear recognition of the value includes men and women from all for regional rail projects through the rail adds to New Zealand’s transport corners of the world, and from diverse Provincial Growth Fund (PGF). system. ethnic backgrounds. There is however still room to improve. The money is being used to address It is a driver of economic development legacy issues to improve reliability and employment, delivered through These are exciting times for rail in and resilience for tracks, signals, our freight network, world-class tourism New Zealand, and we look forward to bridges and tunnels, for new freight services, and the commuter services building a future on the investment that handling equipment and a new freight we enable in Auckland and Wellington. -

Report RO-2014-102: High-Speed Roll-Over, Empty Passenger Train 5153, Westfield, South Auckland, 2 March 2014

Report RO-2014-102: High-speed roll-over, empty passenger Train 5153, Westfield, South Auckland, 2 March 2014 The Transport Accident Investigation Commission is an independent Crown entity established to determine the circumstances and causes of accidents and incidents with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Accordingly it is inappropriate that reports should be used to assign fault or blame or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose. The Commission may make recommendations to improve transport safety. The cost of implementing any recommendation must always be balanced against its benefits. Such analysis is a matter for the regulator and the industry. These reports may be reprinted in whole or in part without charge, providing acknowledgement is made to the Transport Accident Investigation Commission. Final Report Rail inquiry RO-2014-102, high-speed roll-over, empty passenger Train 5153, Westfield, South Auckland 2 March 2014 Approved for publication: February 2015 Transport Accident Investigation Commission About the Transport Accident Investigation Commission The Transport Accident Investigation Commission (Commission) is an independent Crown entity responsible for inquiring into maritime, aviation and rail accidents and incidents for New Zealand, and co-ordinating and co-operating with other accident investigation organisations overseas. The principal purpose of its inquiries is to determine the circumstances and causes of occurrences with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Its purpose is not to ascribe blame to any person or agency or to pursue (or to assist an agency to pursue) criminal, civil or regulatory action against a person or agency. -

Report 99-104 Train 1613 Passenger Safety Incident Featherston 3 April

Report 99-104 Train 1613 passenger safety incident Featherston 3 April 1999 Abstract On Saturday 3 April 1999, Train 1613, the southbound Masterton to Wellington passenger service, departed from Featherston while a scout party and an adult passenger were still loading their gear into the van. Three scouts were left on the platform and a fourth scout and the adult travelled to Upper Hutt in the unlit van. The scouts were at risk as they either alighted from, or attempted to board, the moving train during departure. The guard was unaware of the scouts’ presence in the van. The incident occurred due to a failure to ensure passenger safety prior to the departure of the train. A safety issue identified was the lack of adequate procedures to ensure passenger safety prior to giving right of way. One safety recommendation was made to the operator. The Transport Accident Investigation Commission is an independent Crown entity established to determine the circumstances and causes of accidents and incidents with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Accordingly it is inappropriate that reports should be used to assign fault or blame or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose. The Commission may make recommendations to improve transport safety. The cost of implementing any recommendation must always be balanced against its benefits. Such analysis is a matter for the regulator and the industry. These reports may be reprinted in whole or in part without charge, providing acknowledgement is made to the Transport Accident Investigation Commission. -

Short History of Post-Privatisation in New Zealand by John Wilson

Short History of Post-Privatisation in New Zealand John Wilson, December 2010 This paper is intended to provide an outline history of the experience of privatisation in a series of New Zealand companies, and to provide an assessment of that experience. The companies are: x Ports of AucklandRQHRIWKHFRXQWU\¶VODUJHVWSRUWVSDUWLDOO\SULYDWLVHGE\ one of its regional government owners in 1988, and then brought back fully into regional government ownership in 2005. x Bank of New Zealand (BNZ). One of New ZeDODQG¶VODUJHVWEDQNV7KH%1= has a long history of moving in and out of government ownership. Most recently the government sold its shareholding in the BNZ in 1992 to National Australia Bank. x Air New Zealand1HZ=HDODQG¶VKLVWRULFDOO\GRPLQDQWGRPHVWLFand international airline. The government sold it in 1988 to a consortium. Following a financial collapse in 2001 the government injected new capital and became the dominant shareholder. x Auckland International Airport $,$ 1HZ=HDODQG¶VPRVWLPSRUWDQWDLrport. AIA was originally established as a joint venture between government and Auckland local authorities. The government sold its majority shareholding in AIA by public float in 1998. x Telecom1HZ=HDODQG¶VLQFXPEHQWWHOHSKRQHFRPSDQ\7HOHFRPJUHZXS as part of the Post Office. It was sold to a consortium led by two US telephone companies in 1990; with an agreement the consortium would offer shares to the public. Telecom remains a listed company. x Tranz Rail1HZ=HDODQG¶VRQO\VLJQLILFDQWUDLORSHUDWRUThe government sold LWWRDFRQVRUWLXPLQ,QUHVSRQVHWRWKHLPSOLFDWLRQVRI7UDQ]5DLO¶V declining financial viability, the government progressively bought back Tranz 5DLO¶VDVVHWVEHWZHHQDQG x Trustpower. Originally a local authority owned electricity utility in the Tauranga area, Trustpower took in private capital, and in 1998 bought a set of hydro stations from Electricity Corporation of New Zealand (ECNZ) the then GRPLQDQWHOHFWULFLW\62(7UXVWSRZHULVQRZ1HZ=HDODQG¶Vth largest electricity generator and retailer. -

Presentation for Long Service 2 Contents Editorial ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2015

DECEMBER 2015 THE Transport Worker The journal of the RMTU – NZ's largest specialist transport union Presentation for long service 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2015 5 CONGATULATIONS Wayne Butson Andre Evans one of a number of General secretary members recognised in this issue. RMTU 12 KOREAN CONFERENCE Prepareelcome to the finalfor issue of the2016! Union's magazine for 2015. We are fast approaching the conclusion of what has been a very full on year for many elements of our Union membership. As a result it has been RMTU leaders at the ICLS forum. a challenging time for our paid staff and our priceless elected rank and file national office holders, industrial council reps, branch officers and delegates. WIn 2008 I said in this magazine that there is a famous saying, going back over 3000 16 SOLID SUPPORT years: "Every time history repeats itself, the price goes up." I think we have seen some of that within the rail industry with the election of National-led Governments. You all will be able to think of at least one such event and there are more to come sadly, until an alternative is found to John Key in the minds of more voters. In this issue I have asked all our paid staff to supply a reflection piece on this year and I know you will find them an interesting read. I truly enjoy working with such a team of committed unionists and the passion that they bring to the table on your behalf day in and day out. We are very blessed to have such great experienced Thr RMTU has a reputation for supporting and skilled staff in their fields. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

F.18a 2014 ANNUAL REPORT KiwiRail Overview From 1 January 2013, railway business activities were separated from rail land holdings as a result of a Government restructure carried out to put the business on a more commercial footing. The former parent, New Zealand Railways Corporation (NZRC), continued to hold the 18,000 hectares of rail network land, from which no financial return is expected. The business activities were transferred to a new State Owned Enterprise, KiwiRail Holdings Ltd. NZRC is managed by KiwiRail Holdings Ltd under a long-term nominal fee management agreement, and therefore has limited operational activities. We conduct business in the following areas: Whangarei Logistics: We are a logistics provider to customers who use Dargaville our rail freight and ferry services. Each week, approximately 900 freight trains operate on the KiwiRail network. They carry AUCKLAND bulk freight such as coal and milk, containerised import or export freight to and from ports and full container loads for Hamilton Tauranga Kawerau New Zealand freight forwarders. Three ferries provide the inter- Te Kuiti Kinleith island supply chain link with more than 4000 sailings a year. New Plymouth Taumarunui Shipping: We are an owner and operator of shipping services Stratford Napier operating under the Interislander brand. Of our three ferries, Waiouru Wanganui two are owned and one is chartered. Dannevirke Palmerston North Otaki Tourism Experiences: We provide tourism experiences by Masterton Featherston rail and sea. Three long-distance rail passenger trains - the Picton WELLINGTON Blenheim TranzAlpine, Coastal Pacific and Northern Explorer - provide Westport daily, tri-weekly or seasonal services. Train charters provide Reefton specific rail experiences and service the cruise market. -

The History and Future of Rail in New Zealand

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington The history and future of rail in New Zealand Research Report Prepared by Dave Heatley June 2009 Acknowledgements This project was initiated by Lewis Evans and Glenn Boyle. The author would like to thank them, Bronwyn Howell and Toby Daglish for their assistance. Disclaimer The views expressed in this paper solely reflect those of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of the ISCR or its constituent members. Any errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the author. 1 The history and future of rail in New Zealand Did the 2002-08 re-nationalisation of New Zealand railways represent the end of a failed experiment in the privatisation of essential infrastructure and herald the renaissance of socially-desirable, environmentally-friendly rail? Or was it a misguided attempt to stem the inevitable decline of a 19th century technology that has no place in a modern transportation infrastructure? This report examines the economic viability, structure and role of New Zealand’s rail network since 1863. Rail has become increasingly economically unviable over time. Reflecting this, it has been largely unresponsive to changes in governance and ownership arrangements. Technological change in rail has been minor when compared with the changes in sea, road and air transport. The role of rail has changed as it has adapted to competition from these substitutes. Also examined are various arguments proposed as to why the future may be a break from the past, including externalities (e.g.