Chris Ballantyne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cincinnati's Hard-Won Modern Tram Revival

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com NOVEMBER 2016 NO. 947 CINCINNATI’S HARD-WON MODERN TRAM REVIVAL InnoTrans: The world’s greatest railway showcase Russian cities’ major low-floor orders Stadler and Solaris join for tram bids Doha Metro tunnelling is complete ISSN 1460-8324 £4.25 Berlin Canada’s ‘Radial’ 11 Above and below the Exploring Ontario’s streets of the capital Halton County line 9 771460 832043 LRT MONITOR TheLRT MONITOR series from Mainspring is an essential reference work for anyone who operates in the world’s light and urban rail sectors. Featuring regular updates in both digital and print form, the LRT Monitor includes an overview of every established line and network as well as details of planned schemes and those under construction. POLAND POZNAŃ Tramways play an important role in one of of the main railway station. Poland’s biggest and most historic cities, with In 2012 a line opened to the east of the city, the first horse-drawn tramline opening in 1880. with an underground section containing two An overview Electrification followed in 1898. sub-surface stations and a new depot. The The network was badly damaged during World reconstruction of Kaponiera roundabout, an A high-quality War Two, resuming operations in 1947 and then important tram junction, is set for completion in of the system’s only east of the river Warta. Service returned to 2016. When finished, it will be a three-level image for ease the western side of the city in 1952 with the junction, with a PST interchange on the lower development, opening of the Marchlewski bridge (now named level. -

What Light Rail Can Do for Cities

WHAT LIGHT RAIL CAN DO FOR CITIES A Review of the Evidence Final Report: Appendices January 2005 Prepared for: Prepared by: Steer Davies Gleave 28-32 Upper Ground London SE1 9PD [t] +44 (0)20 7919 8500 [i] www.steerdaviesgleave.com Passenger Transport Executive Group Wellington House 40-50 Wellington Street Leeds LS1 2DE What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review of the Evidence Contents Page APPENDICES A Operation and Use of Light Rail Schemes in the UK B Overseas Experience C People Interviewed During the Study D Full Bibliography P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review Of The Evidence P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review of the Evidence APPENDIX A Operation and Use of Light Rail Schemes in the UK P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review Of The Evidence A1. TYNE & WEAR METRO A1.1 The Tyne and Wear Metro was the first modern light rail scheme opened in the UK, coming into service between 1980 and 1984. At a cost of £284 million, the scheme comprised the connection of former suburban rail alignments with new railway construction in tunnel under central Newcastle and over the Tyne. Further extensions to the system were opened to Newcastle Airport in 1991 and to Sunderland, sharing 14 km of existing Network Rail track, in March 2002. -

2001/02 Annual Plan Vol. I Submissions

2001/02 Annual Plan Vol. I Submissions 16 1 Annual Plan Submissions Note: Those submitters identified in bold type have expressed a desire to be heard in support of their submissions. 1. Norm Morgan Acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick start funding, Water integration, effectiveness of submission process 2. Steve Ritchie Bus service for Robson Street and McManaway Grove , Stokes Valley 3. Nicola Harvey Acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick start funding, Water integration, Marine conservation project for Lyall Bay 4. Alan Waller Rates increases, upgrade to Petone Railway Station 5. John Davis Acquisition of TranzMetro, Water integration, MMP for local government, Emergency management 6. Wellington City Council Floodplain management funding policy 7. Kapiti Coast Grey Power Annual Plan presentation, acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick Assn Inc start funding, rates, operating expenditure, financial management, land management, Parks and Forests, Investment in democracy, 8. John Mcalister Acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick Start funding, Water integration, water supply in the Wairarapa 9. Hutt 2000 Limited Installation of security cameras in Bunny Street Lower 16 Hutt 10. Walk Wellington Inclusion of walking in Regional Land Transport Strategy 11. Hugh Barr Acquisition of TranzMetro, Kick Start funding, Water integration, public access to Water collection areas 2 12. Porirua City Council Bulk Water levy, Transparency of Transport rate, support for Friends of Maara Roa, environmental management and Biodiversity 13. Keep Otaki Beautiful Otaki Bus Shelter 14. Barney Scully Cobham Drive Waterfront/Foreshore 15. Upper Hutt City Council Acquisition of TranzMetro, Water Integration, Hutt River Floodplain Management 16. Wairarapa Green Acquisition of TransMetro, Rick start funding, Issues Network environmental education, rail services, biodiversity 17. -

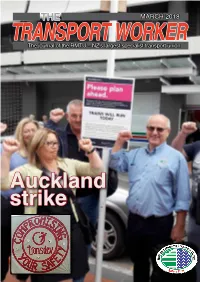

Auckland Strike

THE MARCH 2018 TRANSPORThe journal of the RMTU – NZ'sT largest WORKER specialist transport union Auckland strike 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 1 • march 2018 "On page 14 there is reference to Saida Abad, WHOLE BODY VIBRATION the first female loco 7 engineer in Morocco. I found this billboard with her very moving quote whilst in London recently." Tana Umaga lends a hand to campaign to overcome WBV among LEs. Wayne Butson 10 HISTORIC FIRST General secretary RMTU The entire KiwiRail board made an historic first visit to Hutt workshops Is this the year the recently. MORROCAN CONFERENCE dog bites back? 14 ELCOME to the first issue ofThe Transport Worker magazine for 2018 which, as always, is packed full of just some of the things that your RMTU Union does in the course of its organising for members. delegate Last year ended with a change of Government which should Christine prove to be good news for RMTU members as the governing partners and their sup- Fisiihoi trav- portW partners all have policies which are strongly supportive of rail, ports and the elled all the transport logistics sectors. way to According to the Chinese calendar, 2018 is the year of the dog. However, in my Marrakech view, 2018 is going to be a year of considerable change for RMTU members. We have and was seen Transdev Auckland alter from being a reasonable employer who we have been blown away! doing business with since 2002 to one where dealing with most items has become combative and confrontational. Transdev Wellington is an employer with much less of a working history but we COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Auckland RMTU were able to work with them on the lead up to them taking over the Wellington members pledging solidarity outside Britomart Metro contract and yet, from almost the get go after they took over the running of Place. -

Report 07-101 Express Freight Train 736, Derailment, 309.643 Km, Near

Report 07-101 express freight Train 736, derailment, 5 January 2007 309.643 km, near Vernon The Transport Accident Investigation Commission is an independent Crown entity established to determine the circumstances and causes of accidents and incidents with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Accordingly it is inappropriate that reports should be used to assign fault or blame or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose. The Commission may make recommendations to improve transport safety. The cost of implementing any recommendation must always be balanced against its benefits. Such analysis is a matter for the regulator and the industry. These reports may be reprinted in whole or in part without charge, providing acknowledgement is made to the Transport Accident Investigation Commission. Report 07-101 express freight Train 736 derailment 309.643 km, near Vernon 5 January 2007 Abstract On Friday 5 January 2007, at about 2200, the leading bogie of UK6765, the rear wagon on Christchurch to Picton express freight Train 736, derailed at 309.643 kilometres (km) on the Main North Line. The derailed wagon was dragged a further 3.5 km until it struck the south end main line points at Vernon, derailing the wagon immediately in front. The derailed wagons were pulled another kilometre before the locomotive engineer became aware of the derailed wagons and brought the train to a stop. There were no injuries. A safety issue identified was the current track and mechanical tolerance standards. In view of the safety actions since taken by Toll NZ Consolidated Limited and Ontrack in response to safety recommendations made following similar investigations by the Commission, no further safety recommendations were made. -

RLTP – Submissions from Local Boards, Partners and Key Interest Groups

Submissions on the Draft Regional Land Transport Plan 2021-2031 from local boards, partners and key interest groups Contents Part A – Local Board submissions on the RLTP .............................................................. 1 Albert-Eden Local Board ................................................................................................... 2 Aotea-Great Barrier Local Board ....................................................................................... 6 Devonport-Takapuna Local Board ..................................................................................... 8 Franklin Local Board ........................................................................................................ 14 Henderson-Massey Local Board ...................................................................................... 20 Hibiscus and Bays Local Board ....................................................................................... 25 Howick Local Board ......................................................................................................... 28 Kaipātiki Local Board ....................................................................................................... 30 Māngere-Ōtāhuhu Local Board ....................................................................................... 35 Manurewa Local Board .................................................................................................... 43 Maungakiekie-Tāmaki Local Board ................................................................................. -

Evaluation of Occupational Noise Exposure Levels on the Wellington Suburban Tranz Metro Rail Service

Evaluation of occupational noise exposure levels on the Wellington Suburban Tranz Metro Rail Service 1 Ka’isa Beech and 2 Stuart J McLaren 1 Advanced student at Massey University and Wellington Suburban On-board Staff Member, KiwiRail, Wellington 2 School of Public Health, Massey University, Wellington 2 Email: [email protected] Abstract An occupational noise evaluation study was carried out by Massey University students on locomotive engineers and on-board staff on the two main train sets operating on the Wellington Rail Suburban Network. All measurement results conducted as part of the study show full compliance with the criteria for workplace noise exposure prescribed within the Health and Safety in Employment Regulations 1995. The health and safety noise criterion level permits a maximum dose of 100% which is equivalent to 85 dB LAeq for a normalised 8 hour working day. The highest measured sound exposure was 13% of the total permitted exposure. All occupational noise measurements were observed and written accounts were taken by the three person investigation team. Observations revealed atypical behaviour of one participant which likely compromised one set of readings. This atypical result was removed from the analysis and therefore did not alter the study conclusions. Regardless, such observed behaviour from the study team, reinforces the value of observed real time field monitoring during collection of data. Original peer-reviewed student paper 1. Introduction and purpose of About Ka’isa Beech assessment Age 23, is training to be a The Tranz Metro Rail Passenger Service is operated by Train Traffic Controller KiwiRail and funded by the Greater Wellington Regional with KiwiRail. -

Activist #10, 2009

Rail & Maritime Transport Union Volume ISSUE # 101010 Published Regularly - ISSN 1178-7392 (Print & Online) 1 May 2009 LATEST STATS – UNEMPLOYMENT SHAREHOLDERS ELIGIBLE FOR BENEFIT COMPENSATION FROM TRANZ RAIL Latest statistics released shows that at the CASE end of March 2009, 37,000 working aged A list of the shareholders who are eligible for people (aged 18-64 years) were receiving compensation from the Tranz Rail insider is an Unemployment Benefit. Over the year available from the following Securities to March 2009, the number of recipients of Commission of NZ website link; an Unemployment Benefit increased by 18,000, or 95 percent. The link to the info http://www.seccom.govt.nz/tranz-rail-share- sheet is; refund.shtml#K http://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/abou Shareholders on this list can contact Geoff t-msd-and-our- work/newsroom/factsheets/benefit/2009 Brown on (04) 471 8295 or email /fact-sheet-ub-09-mar-31.doc [email protected] for information about how to claim their compensation. MAY DAY Claimants will need to verify their identity and shareholding details. They should May Day is celebrated and recognized as contact the Commission no later than 24 July the International Workers’ day, chosen over 2009 so that compensation can be paid. 100 years ago to commemorate the struggles and gains of workers and the labour PORTS FORUM movement. Most notable An interesting and reasons to celebrate are challenging programme the 8-hour day, is in store for delegates Saturday as part of the attending the 2009 weekend, improved National Ports Forum in working conditions and Wellington on 5 & 6 child labor laws. -

Honouring Fallen Workers 2 Contents Editorial ISSUE 3 • SEPTEMBER 2016

THE SEPTEMBER 2016 TRANSPORThe journal of the RMTU – NZ'sT largest WORKER specialist transport union Honouring fallen workers 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 3 • SEPTEMBER 2016 13 KIWIRAIL'S INCONSISTENCIES GS Wayne Butson writes an open letter to KiwiRail CEO Peter Reidy about their hypocritical position regarding electric vehicles. Wayne Butson General secretary 15 NEW PICTON HOIST RMTU Kic team welcomes advances in cooperation and the new giant hoist for Picton. Disappointing suburban rail 19 RAIL WELDING MACHINE changeover New facility in HERE are some things we take for granted in the RMTU and one is that we Auckland for mostly deal with employers who want to have a meaningful relationship welding rail could with the union of choice of its workers so they play the employment game be a fore by the rules and pretty fairly. That is not to say that there aren't occasions runner for similar when we have to blow the whistle and call a penalty or ask for a manager to be sent Tfrom the field of play but, by and large, things go according to plan. machines in the South Island. It has therefore been a disappointing, but not wholly unexpected, reawakening to the trickery of some employers for us since 3 July 2016. This is when Transdev Wellington and their sub contractor partner Hyundai Rotem (THR) were handed the keys to the Wellington suburban trainset. Despite working with them for more than three months in the run up to the handover and laboriously working through the mechanics of achieving the "same or more favour- COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Paying respects at able" (S or MF) terms and conditions of employment for our members, it was truly Strongman Mine Disaster Memorial are Ian amazing to behold how quickly they set about trying to change what was just agreed. -

Annual Integrated Report 2019 Welcome – Tēnā Koutou

F.18A KIWIRAIL’S EVOLUTION ANNUAL INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 WELCOME – TĒNĀ KOUTOU Rail has a long and proud history in reservation and tracking system. Those services contribute to our New Zealand, stretching back more We will also be replacing aging purpose of building a better than 150 years. The financial year to locomotives and wagons and improve New Zealand through stronger 30 June 2019 (FY19) has seen the our major maintenance depots at Hutt connections. Government renew that commitment and Waltham. It will also be used to We do this by putting the customer at to rail, laying the foundations for us to progress the procurement of two new, the centre of everything we do, and our play the role we should in delivering for rail-enabled ferries that will replace workers strive every day to meet their the country. Interislander’s aging Aratere, Kaitaki, needs. In the 2019 Budget, the Government and Kaiarahi ferries. allocated $741 million through Vote Our workforce, spread throughout That outstanding level of investment Transport over the next two years and New Zealand, reflects the nation. It made a further $300 million available is a clear recognition of the value includes men and women from all for regional rail projects through the rail adds to New Zealand’s transport corners of the world, and from diverse Provincial Growth Fund (PGF). system. ethnic backgrounds. There is however still room to improve. The money is being used to address It is a driver of economic development legacy issues to improve reliability and employment, delivered through These are exciting times for rail in and resilience for tracks, signals, our freight network, world-class tourism New Zealand, and we look forward to bridges and tunnels, for new freight services, and the commuter services building a future on the investment that handling equipment and a new freight we enable in Auckland and Wellington. -

Transdev Australasia Modern Slavery Statement 2020

Transdev Australasia Modern Slavery Statement 2020 Transdev Australasia Modern Slavery Statement 2020 1 Contents CEO introduction and purpose of this statement 4 Section 1: About Transdev Australasia 6 Section 2: Structure, operations and supply chain of Transdev Australasia 9 Section 3: Modern slavery risks 12 Section: 4: Approach to combating modern slavery at Transdev Australasia 15 Section 5: Measuring Performance and Effectiveness 18 Section 6: Future outlook 20 Section 7: Stakeholder coordination and engagement 21 What is Modern Slavery? The Australian Commonwealth Modern Slavery Act 2018 defines modern slavery as including eight types of serious exploitation: trafficking in persons; slavery; servitude; forced marriage; forced labour; debt bondage; deceptive recruiting for labour or services; and the worst forms of child labour. The worst forms of child labour include situations where children are subjected to slavery or similar practices, or engaged in hazardous work. Transdev Australasia Modern Slavery Statement 2020 2 Transdev Australasia Modern Slavery Statement 2020 3 CEO introduction and purpose of this statement I am pleased to present Transdev Australasia’s modern slavery statement for the reporting year ending 31 December 2020 (this “Statement”), prepared for the purpose of section 16 of the Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth) (the “Act”). This is an inaugural statement pursuant to section 14 of the Act made by reporting entity Transdev Australasia Pty Ltd (Transdev Australasia), a proprietary company limited by shares incorporated under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Transdev Australasia is the parent company and principal governing body of Transdev Australasia’s group of entities and has prepared this Statement on behalf of those entities constituting reporting entities as defined under the Act. -

Report RO-2014-102: High-Speed Roll-Over, Empty Passenger Train 5153, Westfield, South Auckland, 2 March 2014

Report RO-2014-102: High-speed roll-over, empty passenger Train 5153, Westfield, South Auckland, 2 March 2014 The Transport Accident Investigation Commission is an independent Crown entity established to determine the circumstances and causes of accidents and incidents with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Accordingly it is inappropriate that reports should be used to assign fault or blame or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose. The Commission may make recommendations to improve transport safety. The cost of implementing any recommendation must always be balanced against its benefits. Such analysis is a matter for the regulator and the industry. These reports may be reprinted in whole or in part without charge, providing acknowledgement is made to the Transport Accident Investigation Commission. Final Report Rail inquiry RO-2014-102, high-speed roll-over, empty passenger Train 5153, Westfield, South Auckland 2 March 2014 Approved for publication: February 2015 Transport Accident Investigation Commission About the Transport Accident Investigation Commission The Transport Accident Investigation Commission (Commission) is an independent Crown entity responsible for inquiring into maritime, aviation and rail accidents and incidents for New Zealand, and co-ordinating and co-operating with other accident investigation organisations overseas. The principal purpose of its inquiries is to determine the circumstances and causes of occurrences with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Its purpose is not to ascribe blame to any person or agency or to pursue (or to assist an agency to pursue) criminal, civil or regulatory action against a person or agency.