For My Parents, Seah Say Keow and Quek Soh Choo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Download the Report

Burridge Great Britain, Sarah Burrows Great Britain, Gizela Burská Slovakia, James Burton Great Britain, Eleanor Burton Great Britain, Emma Burton Great Britain, Fermin Burzaco Malo Germany, Thierry Busato France, Christian Busch Germany, Charlotte Busche Denmark, Elettra Busetti Italy, Lucia Busetto Italy, Joanna Bush Great Britain, Chantal Buslot Belgium, Angeline Bussche Belgium, Marianna Bussola Italy, Claudia Busuttil Netherlands, Frans Buter Netherlands, Taz Butler Great Britain, Phil Butler Great Britain, Trevor Butlin Great Britain, Leonor Buzaglo Portugal, Agata Buzek Poland, Peppa Buzzi Italy, Noreen Byrne Ireland, Marilyn Byrne Italy, Laura C Estonia, Joan Manuel Caballero Estonia, Susana Caballero Estonia, Jean-Charles Cabanel Estonia, Josette Cabrera France, A Nne Cabrujas Estonia, Marie Ange Cachal France, Teresa Cadete Portugal, Margaret Caffrey Ireland, Michele Caiazza Italy, Marc Cajaravile Estonia, Claudio Cajati Italy, Maria Cal Estonia, Viscardo Calia Italy, Donna Calladine Great Britain, Miquel Callau Estonia, Carlotta Caluzzi Italy, Isabel Camcho Estonia, David Cameira Portugal, Lorna Cameron Great Britain, Melanie Cameron Great Britain, Maria Cameron Great Britain, Sheila Cameron Great Britain, Neil Cameron Great Britain, Tony Camilleri Malta, Philip Camilleri Malta, Cristina Campanella Italy, Mara Campazzi Italy, Editha Campbell Great Britain, Cinzia Campetti Italy, Renato Campino Portugal, Luisa Campos Portugal, Melba Cantera Germany, Martin Cantryn Belgium, Paolo Caoduro Italy, Harley Capa Ireland, Susana Caparrós -

Tourism in Southeast Asia

and parnwell hitchcock, king Tourism is one of the major forces for economic, social and cultural change in the Southeast Asian region and, as a complex multidimensional phenomenon, has attracted increasing scholarly attention during the past TOURISM two decades from researchers from a broad range of disciplines – not least anthropology, sociology, economics, political science, history, development IN SOUTHEAST ASIA studies and business/management. It has also commanded the attention of challenges and new directions policy-makers, planners and development practitioners. However, what has been lacking for many years is a volume that analyses tourism from the major disciplinary perspectives, considers major substantive themes of particular significance in the region (cultural IN TOURISM tourism, ecotourism, romance/sex tourism, etc.), and pays attention to such important conceptual issues as the interaction between local and global, the role of the state in identity formation, authenticity, the creation of ‘tradition’, and sustainability. Such a thorough analysis is offered by Tourism in Southeast Asia, which provides an up-to-date exploration of the state of tourism development and associated issues in one of the world’s most dynamic tourism destinations. The volume takes a close look at many of the challenges facing Southeast Asian tourism at a critical stage of transition and transformation, and following a recent series of crises and disasters. Building on and advancing the path-breaking Tourism in South-East ASIA SOUTHEAST Asia, produced by the same editors in 1993, it adopts a multidisciplinary approach and includes contributions from some of the leading researchers on tourism in Southeast Asia, presenting a number of fresh perspectives. -

East Stand (A)

EAST STAND (A) ACHIE ATWELL • GEORGE BOGGIS • JOHN ELLIOTT • DAVID BREWSTER • GILLIAN ROBINS • DESMOND DESHAUT • PETER CWIECZEK • JAMES BALLARD • PETER TAYLOR • JOHN CLEARY • MARK LIGHTERNESS • TERENCE KERRISON • ANTHONY TROCIAN • GEORGE BURT • JESSICA RICHARDSON • STEVE WICK • BETHAN MAYNARD • MICHAEL SAMMONS • DAN MAUGHAN • EMILY CRANE • STEFANO SALUSTRI • MARTIN CHIDWICK • SOPHIA THURSTON • RICHARD HACK • PHILIP PITT • ROBERT SAMBIDGE • DEREK VOLLER • DAVID PARKINSON • LEONARD COONEY • KAREN PARISH • KIRSTY NORFOLK • SAMUEL MONAGHAN • TONY CLARKE • RAY MCCRINDLE • MIKKEL RUDE • FREDERIC HALLER • JAMIE JAXON • SCOTT JASON • JACQUELINE DUTTON • RICHARD GRAHAM • MATTHEW SHEEHAN • EMILY CONSTABLE • TERRY MARABLE • DANNY SMALLDRIDGE • PAULA GRACE • JOHN ASHCROFT • BARNABY BLACKMAN • JESSICA REYNOLDS • DENNIS DODD • GRAHAM HAWKES • SHAUN MCCABE • STEPHEN RUGGIERO • ALAN DUFFY • BEN PETERS • PAUL SHEPPARD • SIMON WISE • IAN SCOTT • MARK FINSTER • CONNOR MCCLYMONT • JOSEPH O’DRISCOLL • FALCON GREEN • LEAH FINCHAM • ROSS TAYLOR • YONI ADLER • SAMUEL LENNON • IAN PARSONS • GEORGE REILLY • BRIAN WINTER • JOSEPH BROWN • CHARLIE HENNEY • PAUL PRYOR • ROBERT BOURKE • DAREN HALL • DANIEL HANBURY • JOHN PRYOR • BOBBY O’DONOGHUE • ROBERT KNIGHT • BILLY GREEN • MAISIE-JAE JOYCE • LEONARD GAYLE • KEITH JONES • PETER MOODY • ANDY ATWELL DANIEL SEDDON • ROBBIE WRIGHT • PAUL BOWKER • KELLY CLARK • DUNCAN LEVERETT • BILL SINGH • RODNEY CASSAR • ASHER BRILL • MARTIN WILLIAMS • KEVIN BANE • TERRY PORTER • GARETH DUGGAN • DARREN SHEPHERD • KEN CAMPBELL • PHYLLIS -

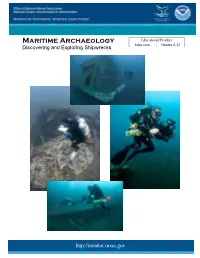

Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks

Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Educational Product Maritime Archaeology Educators Grades 6-12 Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Acknowledgement This educator guide was developed by NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. This guide is in the public domain and cannot be used for commercial purposes. Permission is hereby granted for the reproduction, without alteration, of this guide on the condition its source is acknowledged. When reproducing this guide or any portion of it, please cite NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary as the source, and provide the following URL for more information: http://monitor.noaa.gov/education. If you have any questions or need additional information, email [email protected]. Cover Photo: All photos were taken off North Carolina’s coast as maritime archaeologists surveyed World War II shipwrecks during NOAA’s Battle of the Atlantic Expeditions. Clockwise: E.M. Clark, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Dixie Arrow, Photo: Greg McFall, NOAA; Manuela, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Keshena, Photo: NOAA Inside Cover Photo: USS Monitor drawing, Courtesy Joe Hines http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Monitor National Marine Sanctuary Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and exploring Shipwrecks _____________________________________________________________________ An Educator -

Draft 1 England Athletics Limited

DRAFT ENGLAND ATHLETICS LIMITED (The ‘Company’) Minutes of the Annual General Meeting of the Company held at Athletics House, Alexander Stadium, Perry Barr, Birmingham on Saturday 27 th October 2012 Present: John Graves (Chairman) Executive Chair, England Athletics Peter King Director, England Athletics Chris Jones Interim CEO, England Athletics Graham Jessop Bognor & Chichester AC/Director, England Athletics Michael Heath Enfield & Haringey AC, BAL Director, England Athletics Nigel Rowe Director, England Athletics Wendy Sly Non Executive Director, England Athletics Kevan Taylor Finance Director, England Athletics Peter Crawshaw Achilles Margaret Grayston Wigan Barry Parker Derbyshire AA Peter Cassidy Race Walking Ass & Loughton AC Ian Byett English CC, Basingstoke & Mid Hants AC Stewart Barnes West Midlands Norma Blaine Birchfield Harriers Ted Butcher Colchester & Tendring AC Andy Ward Middlesborough AC Paul Gooding Bedford & County Geoff Durbin Midland Counties Neil Costello Cambridgeshire & Coleridge AC John Aston Cambridgeshire & Coleridge AC Valerie Norrell Cambridgeshire & Coleridge AC Len Quartly Bromsgrove & Redditch AC Geoffrey Morphitis Shaftesbury Barnet Harriers Dave Billiard Birchfield Harriers Rita Brownlie Bromsgrove & Redditch AC Juliet Kavanagh Highgate Harriers Andrew Gardner St Theresa’s AC Jean Hobbs Loughton AC David Hobbs Loughton AC Wendy Haxell Southern Group Andy Day Tamworth AC Debbie Beresford Manchester Harriers Lynette Smith Head of Membership Services, EA David Jeacock Company Solicitor Kate Liggins Finance Manager, England Athletics Sue Banks (mins) PA to Executive, England Athletics 1 DRAFT Apologies: Niels de Vos, Mike Moss, Karen Neale, George Bunner and Alan Barlow The Chairman welcomed all present to the meeting and thanked them for attending. Minutes of the AGM meeting held on 10 th September 2011 The Minutes of the AGM held on 10 th September 2011 had been made available on the website. -

Nhbs Annual New and Forthcoming Titles Issue: 2006 Complete January 2007 [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913

nhbs annual new and forthcoming titles Issue: 2006 complete January 2007 www.nhbs.com [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913 The NHBS Monthly Catalogue in a complete yearly edition Zoology: Mammals Birds Welcome to the Complete 2006 edition of the NHBS Monthly Catalogue, the ultimate buyer's guide to new and forthcoming titles in natural history, conservation and the Reptiles & Amphibians environment. With 300-400 new titles sourced every month from publishers and Fishes research organisations around the world, the catalogue provides key bibliographic data Invertebrates plus convenient hyperlinks to more complete information and nhbs.com online Palaeontology shopping - an invaluable resource. Each month's catalogue is sent out as an HTML Marine & Freshwater Biology email to registered subscribers (a plain text version is available on request). It is also General Natural History available online, and offered as a PDF download. Regional & Travel Please see our info page for more details, also our standard terms and conditions. Botany & Plant Science Prices are correct at the time of publication, please check www.nhbs.com for the latest Animal & General Biology prices. Evolutionary Biology Ecology Habitats & Ecosystems Conservation & Biodiversity Environmental Science Physical Sciences Sustainable Development Data Analysis Reference Mammals Go to subject web page The Abundant Herds: A Celebration of the Sanga-Nguni Cattle 144 pages | Col & b/w illus | Fernwood M Poland, D Hammond-Tooke and L Voigt Hbk | 2004 | 1874950695 | #146430A | A book that contributes to the recording and understanding of a significant aspect of South £34.99 Add to basket Africa's cultural heritage. It is a title about human creativity. -

Marine Cultural and Historic Newsletter Vol 3(5)

Marine Cultural and Historic Newsletter Monthly compilation of maritime heritage news and information from around the world Volume 3.05, 2006 (May)1 his newsletter is provided as a service by the All material contained within the newsletter is excerpted National Marine Protected Areas Center to share from the original source and is reprinted strictly for T information about marine cultural heritage and information purposes. The copyright holder or the historic resources from around the world. We also hope contributor retains ownership of the work. The to promote collaboration among individuals and Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and agencies for the preservation of cultural and historic Atmospheric Administration does not necessarily resources for future generations. endorse or promote the views or facts presented on these sites. The information included here has been compiled from Newsletters are now available in the Cultural and many different sources, including on-line news sources, Historic Resources section of the MPA.gov web site. To federal agency personnel and web sites, and from receive the newsletter, send a message to cultural resource management and education [email protected] with “subscribe MCH professionals. newsletter” in the subject field. Similarly, to remove yourself from the list, send the subject “unsubscribe We have attempted to verify web addresses, but make MCH newsletter”. Feel free to provide as much contact no guarantee of accuracy. The links contained in each information as you would like in the body of the newsletter have been verified on the date of issue. message so that we may update our records. Table of Contents FEDERAL AGENCIES .............................................................................................................................. -

Graduation Ceremonies

2015 Graduation Ceremonies 2015 Graduation Ceremonies This publication was produced by Document Services using environmentally sustainable consumables and technology. 1 Nancy Downes Black Mirror (Mandala) 2014 Gouache on paper 75 x 75 cm This booklet exhibits the outstanding work of graduates of the University of South Australia’s School of Art, Architecture and Design. 2 Chancellor’s welcome Today is a time for celebration, as you mark both the end and the beginning of exciting parts of your lives. It is also an occasion on which to look forward to the opportunities available to you as a graduate of the University of South Australia. I am honoured to be able to share this special event with you, and your family and friends. During your time with the University of South Australia you have developed a set of distinctive qualities which describe the knowledge, skills and personal abilities that you will need as you move into a constantly changing global economy. You have acquired an international outlook; a capacity for critical thought and lifelong learning; an ability to communicate effectively and work autonomously and cooperatively; and a sense of social responsibility. You are well equipped to succeed, confident in the knowledge and skills you possess. Congratulations and all the very best as you start the next big adventure in your lives. Dr Ian Gould AM Chancellor Dr Ian Gould AM BSc(Hons), PhD, FTSE, FAusIMM, CompIEAust Dr Ian Gould has been Chancellor of the University Industry Development Board, the Royal Flying of South Australia since July, 2008. He is a Doctor Service and St Andrew’s Hospital (South geologist with 40 years’ experience in the minerals Australia). -

REDACTED Diver Exposure Scenario for the Portland Harbor Risk Assessment

Diving For Science 2009 Proceeding of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences 28th Scientific Symposium Neal W. Pollock Editor Atlanta, GA March 13-14, 2009 ii The American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS) was formed in 1977 and incorporated in the State of California in 1983 as a 501c6 nonprofit corporation. Visit: www.aaus.org. The mission of AAUS is to facilitate the development of safe and productive scientific divers through education, research, advocacy, and the advancement of standards for scientific diving practices, certifications, and operations. Acknowledgments Thanks to Alma Wagner of the AAUS main office for her organizational efforts and the team from the Georgia Aquarium who hosted many events for the 2009 symposium of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences: Dr. Bruce Carlson Chief Science Officer Jeff Reid Diving Officer Jim Nimz Assistant Diving Officer Mauritius Bell Assistant Diving Officer Special thanks to Kathy Johnston for her original artwork donations (www.kathyjohnston.com) and Kevin Gurr (http://technologyindepth.com) for his dive computer donations. Both provide continued support of the AAUS scholarship program. Cover art by Kathy Johnston. Thanks to Mary Riddle for proof-reading assistance. ISBN 978-0-9800423-3-7 Sea Grant Publication # CTSG-10-09 Copyright © 2010 by the American Academy of Underwater Sciences Dauphin Island Sea Lab, 101 Bienville Boulevard, Dauphin Island, AL 36528 iii Table of Contents Scientific Diving and the Law: an Evolving Relationship Dennis W. Nixon........................................................................................................................1 Diver Exposure Scenario for the Portland Harbor Risk Assessment Sean Sheldrake, Dana Davoli, Michael Poulsen, Bruce Duncan, Robert Pedersen...................7 Submerged Cultural Resource Discoveries in Albania: Surveys of Ancient Shipwreck Sites Derek M. -

JN Bentley Annual Review 2013 6717 Bentleys Annual Review 2013.Qxp Layout 1 09/04/2014 12:50 Page 2

6717 Bentleys Annual Review 2013.qxp_Layout 1 11/04/2014 12:34 Page 1 JN Bentley Annual Review 2013 6717 Bentleys Annual Review 2013.qxp_Layout 1 09/04/2014 12:50 Page 2 Managing Director’s 2013 has been another challenging year for the View business yet we have still managed to deliver the financial results we anticipated. We remain committed to our Health and Safety Strategy, which Through 2013 we have maintained our continues to improve our performance towards our revenue performance with the water frameworks for Anglian Water, target of zero injuries, and we are seeing the Northumbrian Water, Severn Trent Water, benefits of our Cost and Efficiency Strategy as United Utilities and Yorkshire Water. We are in a privileged position with these people around the company become more customers and we should always engaged. These combined have put us in a strong remember how important they are to the business. Working with them provides us position as we continue with the bidding for AMP6 with some fantastic work to be involved in contracts in the water industry. that is not only challenging but has variety and gives us an ability to share our experiences across the frameworks. To do this we will need to make importance of you – our people – work incremental improvements, ensure we are together and are critical to the aspirations When we are at our best we create a team familiar with our systems and processes of the company and all of our futures that is not only interdependent but cares and embrace the opportunity audits together. -

Angajează Dansatoare

VINERI . 6 OCTOMBRIE 2017 WWW.VIATA-LIBERA.RO publicitate hŶŝǀĞƌƐŝƚĂƚĞĂͣƵŶĉƌĞĂĚĞ:ŽƐ͞ĚŝŶ'ĂůĂƜŝ CÂT DE PREGĂTITE SUNT AUTORITĂŢILE SĂ ÎNFRUNTE IARNA CONTRACTE. Iarna ar trebui să nu ia prin surprindere nici municipalitatea şi nici Consiliul Judeţean (CJ), dacă ne raportăm la faptul că atât licitaţia pentru deszăpezire lansată de Ecosal, cât şi cea a autorităţilor judeţene se afl ă pe ultima sută de metri. > pag. 11 l COTIDIAN INDEPENDENT / GALAŢI, ROMÂNIA / ANUL XXVIII, NR. 83XX8522 // 2424 PAGINIPAGINI // 2020 PAGINIPAGINI SUPLIMENTSUPLIMENT TVTV GRATUITGRATUIT // 1,51,5 LEILEI PREJUDICIU URIAŞ DIN FENTAREA FONDULUI PENTRU MEDIU > EVENIMENT/03 ZI LA tate ă n Galaţiul,ţpţ pe lista ă tii din S evaziuniloriil cu ulei ș V.L.“ protestele O mega escrocherie din afacerile cu uleiuri uzate concretizată Sindicali ă într-un prejudiciu de aproape 30 de milioane de euro la Fondul de Mediu, rezultat din neplata taxelor, i-a dus, ieri, pe poliţişti la uşile a nu mai puţin de 17 societăţi comerciale cu puncte de desfacere în toată ţara. M. Constandache continu actual 10 meteo 24˚ Înnorat valuta BNR Ce afaceri au făcut cele mai €4,57 profi tabile companii gălăţene OVIDIU AMĂLINEI niile gălăţene care, în 2016, au lui fi nanciar-fi scal şi ai mediului $3,89 [email protected] obţinut cele mai bune rezultate universitar. Topul fi rmelor a avut GRATUIT economice. Gazdă a evenimen- şi o secţiune de Premii speciale, cu „Viaţa liberă” Cursul de schimb valutar tului, afl at la a XVII-a ediţie, a unul dintre acestea, „Pentru pro- la data de 05.10.2017 Ediţia locală -

Nuneaton Borough 1958-1970 – Part 2 Contents

Nuneaton’s Footballing Heritage Nuneaton Borough 1958-1970 – Part 2 Contents Page No. 1966-1967 ..................................................................................... 236 1967-1968 ..................................................................................... 277 1968-1969 ..................................................................................... 314 1969-1970 ..................................................................................... 352 Acknowledgements ...................................................................... 398 Nuneaton Borough 1958-1970 – Part 2 Signs Pro For Nottingham Forest Sizeable Fee For Alan Carter Borough lef-winger Alan Carter, has been transferred to Worcester City at what Mr Dudley Kernick, the Borough team manager, describes as a “sizeable fee.” Mr Kernick feels that he has adequate cover for Carter. Borough’s New Signings To Face Third Lanark With the exception of Roger Hope, the player signed from Kidderminster, Borough team manager Dudley Kernick, will put out all his new signings for the visit to Manor Park of Third Lanark, the Scottish League side. This will be the first of four pre-season trial games which Mr Kernick has arranged so that supporters can assess the strength of the team against good opposition. Leonard Harris, a seventeen-year-old Borough FC player, has signed professional forms for Notts Forest. He has also arranged these games because four of the first five fixtures are away from home. Borough visit Hillingdon in Harris who has been at Manor Park for the past two seasons, the opening game of the season. Then they play Worcester was spotted by Mr Fred Badham, Borough FC general City away in the Floodlit League, and are at home to manager, while playing for Nuneaton Schools against Cambridge United in a League match, away to Hereford in the a German side. He signed him for Borough when he lef Southern League Cup, and then away to Atherstone Town in Alderman Smith High School.