The French Connection That Contributed to the Fall of a Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Documented Cases of Linguistic Change

APPENDIX I SOME DOCUMENTED CASES OF LINGUISTIC CHANGE 1. Jinghpaw become Shan The first European to visit Hkamti Long (Putao) was Wilcox in 1828. He recorded of the Shan area that 'the mass of the labouring population is of the Kha-phok tribe whose dialect is closely allied to the Singpho'. Other non-Shan dependents of the Shans were the Kha-lang with villages on the Nam Lang 'whose language more nearly resembles that of the Singpho than that of the Nogmung tribe who are on the Nam Tisang'. The prefix 'Kha-' in Hkamti Shan denotes a serf: 'phok' (hpaw) is a term applied by Maru and Hkamti Shans to Jinghpaw. Kha-phok therefore means 'serf Jinghpaw'. In 1925 Barnard described Hkamti Long as he knew it. He noted that the Shan population included a substantial serf class (lok hka) divided into various 'tribes' which he supposes to have been of Tibetan origin, but he remarks: 'I have not been able to obtain even a small vocabulary of their language as they have been absorbed into the Shans whose language and dress they have completely adopted.' It would appear that Barnard's lok hka must include the descendants of Wilcox's Kha-phok and Kha-lang. The inhabitants of 'the villages on the Nam Lang' now speak Shan; but the Jinghpaw-speaking population on the other side of the Mali Hka-who call them selves Duleng-claim to be related to these 'Shans' of the Nam Lang. Of the Nogmung, Barnard recorded: '(They) are gradually being absorbed by the Shans . -

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

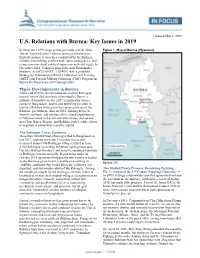

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

A Comparative Study of Amitav Ghosh's the Glass Palace

An Open Access Journal from The Law Brigade Publishers 127 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF AMITAV GHOSH’S THE GLASS PALACE AND SUDHA SHAH’S THE KING IN EXILE Written by Akarshak Bose* & Dr. V Rema** * 4th Year B Tech CSE Student, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Ramapuram, Chennai, India ** Professor and HoD Department of English and Other foreign languages SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Ramapuram ABSTRACT The present study is a comparison between The Glass Palace by Amitav Ghosh and The king in exile by Sudha Shah. Both of them deals with the similar historical plot and shares common places. The Royal Family of Burma King Thibaw , who used to have the unchallenged power of life and death over the Burmese people are now living exile. They have to get approval from the British on every personal matter of their lives. The life in exile was extremely strange and frustrating for the once most powerful family of Burma. The present study also deals with how situation changes and people’s responses or readiness to accept the changes. The Central Character of The Glass Palace Rajkumar when came to Mandalay he had nothing , created an empire of timber and later on he left as a refugee when Japanese invaded their Country, whereas being the king of Burma, when he lost his kingdom to British and deported to India , he was forced to comply with little earning. This comparison in being set up on the grounds of Common places, Common plots and common themes between the two books. Keywords- Amitav Ghosh, Sudha Shah, King Thibaw, Burma, Mandalay, Exile INTRODUCTION The comparative study, between the glass palace by Amitav Ghosh and the king in exile by Sudha Shah shared several things in common. -

The Glass Palace

HISTORY PROJECT “To use the past to justify the present is bad enough—but it’s just as bad to use the present to justify the past.” — Amitav Ghosh, The Glass Palace Srijon Sinha Class XI-H1 – The Shri Ram School, Moulsari THE GLASS PALACE WRITTEN BY AMITAV GHOSH TABLE OF CONTENTS Research Question .......................................................................... 2 Abstract ....................................................................................... 2 Reason for choosing the topic ......................................................................2 Methods and materials ...............................................................................2 Hypothesis ..............................................................................................2 Main Essay .................................................................................... 2 Background and context .............................................................................2 Explanation of the theme ...........................................................................3 Interpretation and analysis .........................................................................5 Conclusion .................................................................................... 5 Bibliography ................................................................................. 6 1 RESEARCH QUESTION What are the historical, cultural and political forces that shape the progression of the plot, the characters, their actions, and furthermore, how do the -

Myanmar Exodus from the Shan State

MYANMAR EXODUS FROM THE SHAN STATE “For your own good, don’t destroy others.” Traditional Shan song INTRODUCTION Civilians in the central Shan State are suffering the enormous consequences of internal armed conflict, as fighting between the tatmadaw, or Myanmar army, and the Shan State Army-South (SSA-South) continues. The vast majority of affected people are rice farmers who have been deprived of their lands and their livelihoods as a result of the State Peace and Development Council’s (SPDC, Myanmar’s military government) counter-insurgency tactics. In the last four years over 300,000 civilians have been displaced by the tatmadaw, hundreds have been killed when they attempted to return to their farms, and thousands have been seized by the army to work without pay on roads and other projects. Over 100,000 civilians have fled to neighbouring Thailand, where they work as day labourers, risking arrest for “illegal immigration” by the Thai authorities. In February 2000 Amnesty International interviewed Shan refugees from Laikha, Murngpan, Kunhing, and Namsan townships, central Shan State. All except one stated that they had been forcibly relocated by the tatmadaw. The refugees consistently stated that they had fled from the Shan State because of forced labour and relocations, and because they were afraid of the Myanmar army. They reported instances of the army killing their friends and relatives if they were found trying to forage for food or harvest crops outside of relocation sites. Every refugee interviewed by Amnesty International said that they were forced to build roads, military buildings and carry equipment for the tatmadaw, and many reported that they worked alongside children as young as 10. -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

Thai-Burmese Warfare During the Sixteenth Century and the Growth of the First Toungoo Empire1

Thai-Burmese warfare during the sixteenth century 69 THAI-BURMESE WARFARE DURING THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY AND THE GROWTH OF THE FIRST TOUNGOO EMPIRE1 Pamaree Surakiat Abstract A new historical interpretation of the pre-modern relations between Thailand and Burma is proposed here by analyzing these relations within the wider historical context of the formation of mainland Southeast Asian states. The focus is on how Thai- Burmese warfare during the sixteenth century was connected to the growth and development of the first Toungoo empire. An attempt is made to answer the questions: how and why sixteenth century Thai-Burmese warfare is distinguished from previous warfare, and which fundamental factors and conditions made possible the invasion of Ayutthaya by the first Toungoo empire. Introduction As neighbouring countries, Thailand and Burma not only share a long border but also have a profoundly interrelated history. During the first Toungoo empire in the mid-sixteenth century and during the early Konbaung empire from the mid-eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries, the two major kingdoms of mainland Southeast Asia waged wars against each other numerous times. This warfare was very important to the growth and development of both kingdoms and to other mainland Southeast Asian polities as well. 1 This article is a revision of the presentations in the 18th IAHA Conference, Academia Sinica (December 2004, Taipei) and The Golden Jubilee International Conference (January 2005, Yangon). A great debt of gratitude is owed to Dr. Sunait Chutintaranond, Professor John Okell, Sarah Rooney, Dr. Michael W. Charney, Saya U Myint Thein, Dr. Dhiravat na Pombejra and Professor Michael Smithies. -

The Military Force of Toungoo Dynasty in the 16Th Century During the Burmese-Siamese War

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, July 2021, Vol. 11, No. 7, 527-537 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2021.07.012 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Military Force of Toungoo Dynasty in the 16th Century During the Burmese-Siamese War XING Cheng Northeastern University, Shenyang, Liaoning Province 110169, China Toungoo Dynasty was a powerful feudal regime in the history of Burma. Upon the rise of Toungoo Dynasty, it sought to extend territory by arms, starting to have wars with the Empire Ming (China), Ayutthaya Dynasty (Siam/Thailand) and Lan Xang (Laos). The war between Burma and Siam lasted for more than two centuries, from 1548 to 1810. However, from strategy view, the whole Burmese-Siamese War was the game between China (Ming and Qing Dynasties) and Burma (Toungoo and Konbaung Dynasties). In the whole process, most of the fierce battles took place in the 16th century, the inception phase of the war. So, the 16th century was a very important period for us if we want to have a research on the military force of Toungoo Dynasty. Keywords: Burma, Toungoo Dynasty, Tabinshwehti, Bayinnaung, Siam, Ayutthaya Dynasty Ⅰ Introduction Toungoo Dynasty was an important feudal regime in the history of Burma which was built by military means. This system deeply influenced the development of Burma. Until modern times, in Burma, military governments still appear now and then. In the 16th century, Burma had the best military potentials in Southeast Asia because of its special military system, letting it have the ability to mobilize a large army when the wars came. Benefiting from the Empire Ming’s conservative policy and the relatively weak military power of other Southeast Asian countries, Toungoo Dynasty rapidly started its expansion. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Buddhism, Power and Political Order

BUDDHISM, POWER AND POLITICAL ORDER Weber’s claim that Buddhism is an otherworldly religion is only partially true. Early sources indicate that the Buddha was sometimes diverted from supra- mundane interests to dwell on a variety of politically related matters. The significance of Asoka Maurya as a paradigm for later traditions of Buddhist kingship is also well attested. However, there has been little scholarly effort to integrate findings on the extent to which Buddhism interacted with the polit- ical order in the classical and modern states of Theravada Asia into a wider, comparative study. This volume brings together the brightest minds in the study of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Their contributions create a more coherent account of the relations between Buddhism and political order in the late pre-modern and modern period by questioning the contested relationship between monastic and secular power. In doing so, they expand the very nature of what is known as the ‘Theravada’. This book offers new insights for scholars of Buddhism, and it will stimulate new debates. Ian Harris is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cumbria, Lancaster, and was Senior Scholar at the Becket Institute, St Hugh’s College, University of Oxford, from 2001 to 2004. He is co-founder of the UK Association for Buddhist Studies and has written widely on aspects of Buddhist ethics. His most recent book is Cambodian Buddhism: History and Practice (2005), and he is currently responsible for a research project on Buddhism and Cambodian Communism at the Documentation Center of Cambodia [DC-Cam], Phnom Penh. ROUTLEDGE CRITICAL STUDIES IN BUDDHISM General Editors: Charles S. -

Displacement of Nation in the Glass Palace

International Journal of Language and Literature June 2015, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 120-123 ISSN: 2334-234X (Print), 2334-2358 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2015. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijll.v3n1a15 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijll.v3n1a15 Displacement of Nation in the Glass Palace N. Sukanya 1 & Dr. S. Sobana 2 Abstract Nation has been considered as a form of “restrictively imagined collectivities” (Anderson 147) by Amitav Ghosh in “A Correspondence on Provincializing Europe ” that creates hindrances in writing about the individual identity. This makes several writers deal with family centered novels and their conflicts. They find a way out from discussing the concept of nation by dealing with families in their works. Amitav Ghosh is one such writer who has displaced himself from bringing in the concept of nation in his 2001 Frankfurt International e- Book Award winning novel, The Glass Palace . Ghosh has brought in the lives of a few individuals linked in families and their experiences under one umbrella. Moreover, he makes those individuals search for a space that moves them away from the confinement of nation. This historical novel has portrayed the struggles faced by the people during the fall of the Konbaung Dynasty in Mandalay. Through these imaginary characters, Ghosh has displaced the notion of nation and has paved prominence to the family ties that revolve around their own inner conflicts which have a different imaginary concreteness from that of other countries like Europe and America. Keywords: Amitav Ghosh, displacement, nation, homogeneous, heterogeneous, family ties, confinement Introduction Nation has been considered as an “imagined political community” (Anderson 1991) by Benedict Anderson in his Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. -

Burma's Foreign Policy with Particular Referenc E to India

X BURMA'S FOREIGN POLICY WITH PARTICULAR REFERENC E TO INDIA A B S T R A C T THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE B y IV:iSS ASHA SHARMA Under the Supervision of Professor Syed Nasir Ali Department of Political bcienc* Dcpariment of Political Science ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, A L I G A R H 1974 ABSTRACT Buitna functions as a link between the two big countries of East, India and China. It is true that inspite of Burma being governed for a long period as a part of Indian Empire, one knows very little about this country, Burma gradually achieved great importance not only for India but also for Southeast Asia and Singapore, Burma is of great importance for the defence system of India and Southeast Asia, It was a great puzzle for the outside world. Its aloofness from its neighbour and Its self imposed isolation was an enigma for its neighbours, Burma road and the use of the port of Rangoon acquired great strategic importance. The closing of this road had a great effect on China, the U.S.A. and the Soviet Union and hence provoked many sided protest. The main feature of Burma is that it is an isolated country both politically and geographically, NAgas >*io lived on the borders, repeatedly created a great trouble for the Indian government. Hence It Is necessary for India that the government of Burma should be neutral and amenable to the Interests of Its neighbours, Oua to the formation of a new state of Pakistan in 1947, great danger to the defence of India was posed by the hostile posture of this new state.