Heritage in the Myanmar Frontier: Shan State, Haws, and Conditions for Public Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur's Ahoms

High Technology Letters ISSN NO : 1006-6748 The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur’s Ahoms - An Ethnographic Approach Barnali Chetia, PhD, Assistant Professor, Indian Institute of Information Technology, Vadodara, India. Department of Linguistics Abstract- Mong Dun Shun Kham, which in Assamese means xunor-xophura (casket of gold), was the name given to the Ahom kingdom by its people, the Ahoms. The advent of the Ahoms in Assam was an event of great significance for Indian history. They were an offshoot of the great Tai (Thai) or Shan race, which spreads from the eastward borders of Assam to the extreme interiors of China. Slowly they brought the whole valley under their rule. Even the Mughals were defeated and their ambitions of eastward extensions were nipped in the bud. Rangpur, currently known as Sivasagar, was that capital of the Ahom Kingdom which witnessed the most glorious period of its regime. Rangpur or present day sivasagar has many remnants from Ahom Kingdom, which ruled the state closely for six centuries. An ethnographic approach has been attempted to trace the history of indigenous culture and traditions of Rangpur's Ahoms through its remnants in the form of language, rites and rituals, religion, archaeology, and sacred sagas. Key Words- Rangpur, Ahoms, Culture, Traditions, Ethnography, Language, Indigenous I. Introduction “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.” -P.B Shelley Rangpur or present day Sivasagar was one of the most prominent capitals of the Ahom Kingdom. -

Assistance for Ethnic Minorities in Myanmar Through ODA (PDF, 312KB)

Chapter 1: ODA for Moving Forward Together Section 1: ODA for Achieving a Free, Prosperous, and Stable International Community – Assistance for democratization and national reconciliation Part I ch.1 ODA Assistance for Ethnic Minorities Topics in Myanmar through ODA ■ Surrounding ethnic minorities issues towards national reconciliation, including the peace process with ethnic minorities. Promoting regional development and Myanmar is said to be home to 135 different ethnic groups. the consolidation of peace, Japan will proactively implement Of these, the Bamar occupy about 70% of the population, assistance in ethnic minorities’ areas in order to contribute to living mainly in the central plains region. The ethnic the stable and sustainable growth of Myanmar. minorities that account for the remaining 30% primarily live Japan has thus far implemented assistance for ethnic in the mountainous regions near national borders. These minority regions based on the issues and needs of each state, minorities are broadly divided into seven major national focusing its support in the area of agriculture, which is their races, which are: Kachin, Kayah (Karenni), Karen (Kayin), primary industry. Chin, Mon, Shan, and Rakhine (Arakan). The races are To name a few, rural development assistance (technical further broken down into 134 ethnic groups. cooperation) has been provided in the northern area of Shan The issues surrounding ethnic minorities in Myanmar are State for the dissemination and distribution of drug crop deeply rooted and were caused by the “divide and rule” alternatives. In the southern part of Shan State, production administration during British colonial period. Even after and distribution assistance in the development of sustainable gaining independence in 1948, conflict between the national circular agriculture was provided by working with NPO military and ethnic armed groups continued for 60 years in Terra People Association on a technical cooperation. -

Die Karen: Ideologie, Interessen Und Kultur

Die Karen: Ideologie, Interessen und Kultur Eine Analyse der Feldforschungsberichte und Theorienbildung Magisterarbeit zur Erlangung der Würde des Magister Artium der Philosophischen Fakultäten der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität zu Freiburg i. Br. 1992 vorgelegt von Reiner Buergin aus Weil am Rhein (Ausdruck vom Februar 2000) Inhaltsverzeichnis: Einleitung 1 Thema, Ziele, Vorgehensweise 5 2 Übersicht über die Literatur 6 I Die Karen in Südostasien/Einführung 9 1 Bezeichnungen und Sprache 9 2 Verbreitung der verschiedenen Gruppen und Demographie 10 3 Wirtschaftliche Verhältnisse 12 a) Brandrodungsfeldbau 12 b) Naßreisanbau 13 c) Sonstige wirtschaftliche Tätigkeiten und ökomische Krise 14 4 Soziale und politische Organisation 15 a) Entwicklung der Siedlungsform 15 b) Familie und Haushalt 16 c) Verwandtschaftsstrukturen und -gruppen 17 d) Die Dorfgemeinschaft 17 e) Die Territorialgemeinschaft 18 f) Nationalstaatliche Integration 19 5 Religion und Weltbild 20 a) Traditionelle Religionsformen 20 b) Religiöser Wandel, Buddhismus und Christentum 21 c) Mythologie, Weltbild und Werthaltung 22 II Geschichte der verschiedenen Gruppen 1 Ursprung und Einwanderung nach Hinterindien 24 a) Ursprung der Karen 24 b) Einwanderung nach Hinterindien 25 2 Karen in Hinterindien von ca. 1200 - 1800 25 a) Sgaw und Pwo in Burma 25 b) Die Kayah 27 c) Karen in Thailand 28 3 Karen in Burma und Thailand im 19. Jh. 29 a) Sgaw und Pwo in Burma 29 b) Sgaw und Pwo in Siam 31 c) Sgaw und Pwo in Nordthailand 32 d) Die Kayah im 19. Jahrhundert 33 2 4 Karen in Burma und Thailand -

Report on "Youth Perceptions of Pluralism and Diversity in Yangon

YOUTH PERCEPTIONS OF PLURALISM AND DIVERSITY IN YANGON, MYANMAR Report prepared for UNESCO by Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 22 November 2019 Yangon, Myanmar YOUTH PERCEPTIONS OF PLURALISM AND DIVERSITY IN YANGON, MYANMAR Executive summary 3 Introduction 5 Literature Review 6 Education 6 Isolation and Public and Cultural Spaces 6 Religion and Ethnicity 7 Histories and Memories of Coexistence, Friendship, and Acceptance 7 Discrimination and Burmanization 7 Parents, Teachers, and Lessons: Hierarchy and Social Norms 8 Social Media 8 Methodology 10 Ethnic and Religious Communities 11 Research Findings 13 Perceptions of Cultural Diversity, Pluralism and Tolerance 13 Discrimination, Civil Documentation and Conflict 15 Case Study 17 Socialization: Parents, Peers, and Lessons 19 Proverbs, Idioms, Mottos 19 Peers and Friends 20 Parents and Elders 21 Education (Schools, Universities and Teachers) 22 Isolation and Space 26 Festivals, Holidays, and Cultural and Religious Sites 27 Civic and Political Participation 29 Social Media and Hate Speech 30 Employment and Migration 31 Language 32 Change Agents 33 Conclusion 35 Recommendations for Program Expansion 37 Civil Society Mapping 38 References 41 2 YOUTH PERCEPTIONS OF PLURALISM AND DIVERSITY IN YANGON, MYANMAR Executive summary A number of primary gaps have been identified in the existing English language literature on youth, diversity, and pluralism in Myanmar that have particular ramifications for organizations and donors working in the youth and pluralism space. The first is the issue of translation. Most of the existing literature makes no note of how concepts such as diversity, tolerance, pluralism and discrimination are translated into Burmese or if there is a pre-existing Burmese concept or framework for these concepts, and particularly, how youth are using and learning about these concepts. -

Islamic Education in Myanmar: a Case Study

10: Islamic education in Myanmar: a case study Mohammed Mohiyuddin Mohammed Sulaiman Introduction `Islam', which literally means `peace' in Arabic, has been transformed into a faith interpreted loosely by one group and understood conservatively by another, making it seem as if Islam itself is not well comprehended by its followers. Today, it is the faith of 1.2 billion people across the world; Asia is a home for 60 per cent of these adherents, with Muslims forming an absolute majority in 11 countries (Selth 2003:5). Since the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, international scholars have become increasingly interested in Islam and in Muslims in South-East Asia, where more than 230 million Muslims live (Mutalib 2005:50). These South-East Asian Muslims originally received Islam from Arab traders. History reveals the Arabs as sea-loving people who voyaged around the Indian Ocean (IIAS 2005), including to South-East Asia. The arrival of Arabs has had different degrees of impact on different communities in the region. We find, however, that not much research has been done by today's Arabs on the Arab±South-East Asian connection, as they consider South-East Asia a part of the wider `East', which includes Iran, Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Indeed, the term `South-East Asia' is hardly used in modern Arab literature. For them, anything east of the Middle East and non-Arabic speaking world is considered to be `Asia' (Abaza 2002). According to Myanmar and non-Myanmar sources, Islam reached the shores of Myanmar's Arakan (Rakhine State) as early as 712 AD, via oceangoing merchants, and in the form of Sufism. -

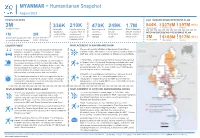

Myanmar – Humanitarian Snapshot (August 2021)

MYANMAR – Humanitarian Snapshot August 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED 2021 HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE PLAN 3M 336K 210K 470K 249K 1.7M 944K $276M $97M (35%) People targeted Requirements Received People in need Internally People internally Non-displaced Returnees and Other vulnerable displaced displaced due to stateless locally people, mostly in INTERIM EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN 1M 2M people at the clashes and persons in integrated urban and peri- start of 2021 Rakhine people urban areas people previously identified people identified insecurity since 2M $109M $17M (15%) February 2021 in conflict-affected areas since 1 February People targeted Requirements Received COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT IN KACHIN AND SHAN A total of 3 million people are targeted for humanitarian The overall security situation in Kachin and Shan states assistance across the country. This includes 1 million remains volatile, with various level of clashes reported between people in need in conflict-affected areas previously MAF and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or among EAOs. identified and a further 2 million people since 1 February. Monsoon flash floods affected around 125,000 people in In Shan State, small-scale population movement was reported the regions and states of Kachin, Kayin, Mandalay, Mon, in Hsipaw, Muse, Kyethi and Mongkaing townships since mid- Rakhine, eastern Shan and Tanintharyi between late July July. In total, 24,950 people have been internally displaced and mid-August, according to local actors. Immediate across Shan State since the start of 2021; over 5,000 people needs of families affected or evacuated have been remain displaced in five townships. addressed by local aid workers and communities. In Kachin, no new displacement has been reported. -

Shan State - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit SHAN STATE - MYANMAR Mohnyin 96°40'E Sinbo 97°30'E 98°20'E 99°10'E 100°0'E 100°50'E 24°45'N 24°45'N Bhutan Dawthponeyan India China Bangladesh Myo Hla Banmauk KACHIN Vietnam Bamaw Laos Airport Bhamo Momauk Indaw Shwegu Lwegel Katha Mansi Thailand Maw Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Konkyan Cambodia 24°0'N Muse 24°0'N Muse Manhlyoe (Manhero) Konkyan Namhkan Tigyaing Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Laukkaing Mabein Tarmoenye Takaung Kutkai Chinshwehaw CHINA Mabein Kunlong Namtit Hopang Manton Kunlong Hseni Manton Hseni Hopang Pan Lon 23°15'N 23°15'N Mongmit Namtu Lashio Namtu Mongmit Pangwaun Namhsan Lashio Airport Namhsan Mongmao Mongmao Lashio Thabeikkyin Mogoke Pangwaun Monglon Mongngawt Tangyan Man Kan Kyaukme Namphan Hsipaw Singu Kyaukme Narphan Mongyai Tangyan 22°30'N 22°30'N Mongyai Pangsang Wetlet Nawnghkio Wein Nawnghkio Madaya Hsipaw Pangsang Mongpauk Mandalay CityPyinoolwin Matman Mandalay Anisakan Mongyang Chanmyathazi Ai Airport Kyethi Monghsu Sagaing Kyethi Matman Mongyang Myitnge Tada-U SHAN Monghsu Mongkhet 21°45'N MANDALAY Mongkaing Mongsan 21°45'N Sintgaing Mongkhet Mongla (Hmonesan) Mandalay Mongnawng Intaw international A Kyaukse Mongkaung Mongla Lawksawk Myittha Mongyawng Mongping Tontar Mongyu Kar Li Kunhing Kengtung Laihka Ywangan Lawksawk Kentung Laihka Kunhing Airport Mongyawng Ywangan Mongping Wundwin Kho Lam Pindaya Hopong Pinlon 21°0'N Pindaya 21°0'N Loilen Monghpyak Loilen Nansang Meiktila Taunggyi Monghpyak Thazi Kenglat Nansang Nansang Airport Heho Taunggyi Airport Ayetharyar -

THAN, TUN Citation the ROYAL ORDERS of BURMA, AD 1598-1885

Title Summary of Each Order in English Author(s) THAN, TUN THE ROYAL ORDERS OF BURMA, A.D. 1598-1885 (1988), Citation 7: 1-158 Issue Date 1988 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/173887 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University THE ROYAL ORDERS OF BURMA, AD 1598-1885 The Roya 1Orders of Burma, Part Seven, AD 1811-1819 Summary 1 January 18 1 1 Order:( 1) According to statements made by the messengers from Ye Gaung Sanda Thu, Town Officer, Mogaung, arrest Ye Gaung Sanda Thu and bring him here as a prisoner; send an officer to succeed him in Mogaung as Town Officer. < 2) The King is going to plant the Maha Bodhi saplings on 3 January 1811; make necessary preparations. This Order was passed on 1 January 1811 and proclaimed by Baya Kyaw Htin, Liaison Officer- cum -Chief of Caduceus Bearers. 2 January 18 1 1 Order:( 1) Officer of Prince Pyay (Prome) had sent here thieves and robbers that they had arrested; these men had named certain people as their accomplices; send men to the localities where these accused people are living and with the help of the local chiefs, put them under custody. ( 2) Prince Pakhan shall arrest all suspects alledged to have some connection with the crimes committed in the villages of Ka Ni, Mait Tha Lain and Pa Hto of Kama township. ( 3) Nga Shwe Vi who is under arrest now is proved to be a leader of thieves; ask him who were his associates. This Order was passed on 2 January 1811 and proclaimed by Zayya Nawyatha, Liaison Officer. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

A Case Study from Myanmar How to Inform, Empower, and Impact Communities

INFORMATION ECOSYSTEMS in transition: A case stUDY from myanmar HOW to inform, emPOWer, anD imPact commUnities Mon State, Myanmar Pilot Study PART ONE: RESEARCH FINDINGS ABOUT THE AUTHORS ABOUT THE RESEARCH TEAM EXecUtiVE SUmmary Andrew Wasuwongse is a graduate of the Johns Hopkins Established in 1995, Myanmar Survey Research (MSR) University’s School of Advanced International Studies in is a market and social research company based in Washington, DC. He holds a master’s degree in International Yangon, Myanmar. MSR has produced over 650 Relations and International Economics, with a concentration research reports in the fields of social, market, and in Southeast Asia Studies. While a research assistant for environmental research over the past 16 years for UN the SAIS Burma Study Group, he supported visits by three agencies, INGOs, and business organizations. Burmese government delegations to Washington, DC, including officials from Myanmar’s Union Parliament, ABOUT INTERNEWS in MYANMAR Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Industry. He has worked as a consultant for World Vision Myanmar, where he led an Internews is an international nonprofit organization whose assessment of education programs in six regions across mission is to empower local media worldwide to give people Myanmar, and has served as an English teacher in Kachin the news and information they need, the ability to connect State, Myanmar, and in Thailand on the Thai-Myanmar border. and the means to make their voices heard. Internews He speaks Thai and Burmese. provides communities with the resources to produce local news and information with integrity and independence. Alison Campbell is currently Internews’ Senior Director With global expertise and reach, Internews trains both media for Global Initiatives based in Washington, DC, overseeing professionals and citizen journalists, introduces innovative Internews’ environmental, health and humanitarian media solutions, increases coverage of vital issues and helps programs. -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

Thai-Burmese Warfare During the Sixteenth Century and the Growth of the First Toungoo Empire1

Thai-Burmese warfare during the sixteenth century 69 THAI-BURMESE WARFARE DURING THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY AND THE GROWTH OF THE FIRST TOUNGOO EMPIRE1 Pamaree Surakiat Abstract A new historical interpretation of the pre-modern relations between Thailand and Burma is proposed here by analyzing these relations within the wider historical context of the formation of mainland Southeast Asian states. The focus is on how Thai- Burmese warfare during the sixteenth century was connected to the growth and development of the first Toungoo empire. An attempt is made to answer the questions: how and why sixteenth century Thai-Burmese warfare is distinguished from previous warfare, and which fundamental factors and conditions made possible the invasion of Ayutthaya by the first Toungoo empire. Introduction As neighbouring countries, Thailand and Burma not only share a long border but also have a profoundly interrelated history. During the first Toungoo empire in the mid-sixteenth century and during the early Konbaung empire from the mid-eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries, the two major kingdoms of mainland Southeast Asia waged wars against each other numerous times. This warfare was very important to the growth and development of both kingdoms and to other mainland Southeast Asian polities as well. 1 This article is a revision of the presentations in the 18th IAHA Conference, Academia Sinica (December 2004, Taipei) and The Golden Jubilee International Conference (January 2005, Yangon). A great debt of gratitude is owed to Dr. Sunait Chutintaranond, Professor John Okell, Sarah Rooney, Dr. Michael W. Charney, Saya U Myint Thein, Dr. Dhiravat na Pombejra and Professor Michael Smithies.