A Cta ΠCumenica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Synod 2015 – Primus' Charge He Was a Good Man, Full Of

General Synod 2015 – Primus’ Charge He was a good man, full of the Holy Spirit and of faith. Barnabas was of course the encourager. As we approach the work of our General Synod, we should be encouraged - we too should be full of the Holy Spirit and of faith. Jesus tells us that 'we should love one another as I have loved you'. And the pinnacle of Christ-like love is the love than which there is no greater - to lay down one’s life for one's friends. I hear those words of scripture as themselves an encouragement to us - an encouragement to transcend what we expect of a General Synod; an encouragement to strive to act as a community of faith and of love as we transact our business - some of it routine and some of it about things which stir passions; an encouragement to sustain visible unity in Christ as we do God's work together. There are many things in the work which we shall do during the next few days which in themselves are encouraging. I think particularly of the development of the Scottish Episcopal Institute, the continuing development of the Whole Church Mission and Ministry Policy, the breadth of our interests and concerns as expressed in the work of the Church in Society Committee, the quality, faithfulness and the missional shape of our administration. The most significant challenge to us as a Christian community comes as we address the questions around Same-Sex Marriage. In this too, we should be full of the Holy Spirit and of faith - people who love and sacrifice for one another? I believe that that time has come when we must address this fundamental issue of our times. -

The Story of a Chair the Reality of Candlemas

February 2021 lntothe Adult Formation & Enrichment: Deepening our Catholic faith & identity Chair of Peter by Bernini deep Location: St. Peter’s Basilica This ancient chair, however, is much more The Story of a Chair of than an exquisitely-detailed physical object The Reality Candlemas “Upon this rock I will build my Church...” (MT 16:18) “…And the lord whom you seek will come suddenly to his designed by an Italian master. In his General temple; The messenger of the covenant whom you desire - High above the altar, within the apse of St. Audience of February 2006, Pope Benedict see, he is coming! says the LORD of hosts.” (Malachi 3:1) XVI spoke to the spiritual authority that the Peter’s Basilica and beneath the Holy Spirit Amidst the dash to store holiday stained-glass window sits Bernini’s Cathedra chair also represents: decorations or predict the outcome of Petri (Chair of Peter). But what one finds on “On it, we give thanks to God for the mission He Groundhog Day is the often overlooked display is not the original chair. Pictured entrusted to the Apostle Peter and his sacred day that for many marks the official Successors...The See of Rome, after St. Peter’s below is the first design which The Catholic end to the Christmas season: the Feast of travels, came to be recognized as the See of the the Presentation of the Lord, or Encyclopedia describes in this way: Successor of Peter, and its Bishop’s cathedra Candlemas, on February 2nd. The story of (chair) represented the mission entrusted to him “...the oldest portion is a by Christ to tend his entire flock.. -

Catalogue-Guided-Tours-Kids.Pdf

C A T A L O G U E G U I D E D T O U R S K I D S E D I T I O N The Colosseum, the largest amphitheater in the world Duration: 2 hours Our guide will be waiting for you in front of the Colosseum, the largest and most famous amphitheater in the world. You will discover together what happened inside this "colossal" building where about 50,000 spectators could enter to watch the gladiator shows offered by the Roman emperors until the fifth century. Place of incredible fun for the ancient Romans. Exotic animals, gladiators acclaimed and loved as heroes, spectacular death sentences and grandiose naumachiae. We will unveil many curiosities and false legends about the largest amphitheater in the world. The Palatine, from the Hut of Romulus to the Imperial Palace Duration: 2 hours A long time ago, between history and legend, Rome was born ... but where exactly?! On the Palatine Hill! We will start from the mythical origin of the Eternal City, when the two brothers Romulus and Remus fought for its dominion, discovering that everything started from small wooden huts, to arrive in an incredible journey through time and archaeology to the marbles and riches of the imperial palaces, admired throughout the ancient world. You will meet kings and emperors, but also shepherds and farmers! Castel Sant'Angelo, the Mausoleum of Hadrian Duration: 2 hours Our guide will be waiting for you in front of the Castle's main door to let you discover the secrets of one of the most famous monuments of ancient Rome. -

Come Join Us!

MISSION STATEMENT OUR LADY OF SORROWS IS A CATHOLIC COMMUNITY DEDICATED TO GIVING WITNESS TO JESUS CHRIST BY PROCLAIMING THE GOSPEL, CELEBRATING THE SACRAMENTS AND SERVING OTHERS. February 17, 2019 COME JOIN US! Due to last Tuesday’s inclement weather, This event has been rescheduled for Tuesday, February 19 Doors open at 6:30 p.m., Dreaming begins at 7:00 p.m. REGISTER ONLINE AT DynamicCatholic.com/Dreams SAVE THE DATE — COMING THIS LENT CǘǢǙǣǤ LǕǑǦǕǣ HǟǝǕ HǙǣ BǥǣǙǞǕǣǣ CǘǢǙǣǤ FǑǤǘǕǢ’ǣ Tǟ Dǟ HǙǣ Page 2 Our Lady of Sorrows Church, Farmington W O R S H I P LITURGICAL SERVICES Saturday, February 16, 2019 8:00 a.m. Giovanni Montebelli req. by Graziano Canini The Lord’s Day Saturday Vigil: 4:30 pm 4:30 p.m. George & Therese Kapolnek req. by Jeff & Karen Paterson Sunday: 8:00, 9:30, 11:15 am, Margaret Kraft req. by The Family 1:00 & 5:30 pm Intentions of Fr. Paul Graney req. by Sam & Paulette Lucido Daily Mass Sunday, February 17, 2019 ►(See schedule on this page) 8:00 a.m. Susan Meldrum req. by The Dix Family Sacrament of Reconciliation Tuesday: 6:30 - 7:00 pm 9:30 a.m. Genevieve Wiktor req. by Mark & Judi McInerney M See the complete Saturday: 3:00 - 4:00 pm 11:15 a.m. Intentions of All Parishioners Daily Mass (Confessions may also be arranged by 1:00 p.m. Giovanni Montebelli req. by Graziano Canini Schedule on this page. calling one of the priests for an appointment.) A Ruth Nicholls req. -

Statistical Bulletin 20 17 1 - Quarter Quarter 1

quarter 1 - 2017 Statistical Bulletin quarter 1 Statistical Bulletin Statistical publications and distribution options Statistical publications and distribution options The Bank of Italy publishes a quarterly statistical bulletin and a series of reports (most of which are monthly). The statistical information is available on the Bank’s website (www.bancaditalia.it, in the Statistical section) in pdf format and in the BDS on-line. The pdf version of the Bulletin is static in the sense that it contains the information available at the time of publication; by contrast the on-line edition is dynamic in the sense that with each update the published data are revised on the basis of any amendments received in the meantime. On the Internet the information is available in both Italian and English. Further details can be found on the Internet in the Statistics section referred to above. Requests for clarifications concerning data contained in this publication can be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. The source must be cited in any use or dissemination of the information contained in the publications. The Bank of Italy is not responsible for any errors of interpretation of mistaken conclusions drawn on the basis of the information published. Director: GRAZIA MARCHESE For the electronic version: registration with the Court of Rome No. 23, 25 January 2008 ISSN 2281-4671 (on line) Notice to readers Notice to readers I.The appendix contains methodological notes with general information on the statistical data and the sources form which they are drawn. More specific notes regarding individual tables are given at the foot of the tables themselves. -

HCS — History of Classical Scholarship

ISSN: 2632-4091 History of Classical Scholarship www.hcsjournal.org ISSUE 1 (2019) Dedication page for the Historiae by Herodotus, printed at Venice, 1494 The publication of this journal has been co-funded by the Department of Humanities of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and the School of History, Classics and Archaeology of Newcastle University Editors Lorenzo CALVELLI Federico SANTANGELO (Venezia) (Newcastle) Editorial Board Luciano CANFORA Marc MAYER (Bari) (Barcelona) Jo-Marie CLAASSEN Laura MECELLA (Stellenbosch) (Milano) Massimiliano DI FAZIO Leandro POLVERINI (Pavia) (Roma) Patricia FORTINI BROWN Stefan REBENICH (Princeton) (Bern) Helena GIMENO PASCUAL Ronald RIDLEY (Alcalá de Henares) (Melbourne) Anthony GRAFTON Michael SQUIRE (Princeton) (London) Judith P. HALLETT William STENHOUSE (College Park, Maryland) (New York) Katherine HARLOE Christopher STRAY (Reading) (Swansea) Jill KRAYE Daniela SUMMA (London) (Berlin) Arnaldo MARCONE Ginette VAGENHEIM (Roma) (Rouen) Copy-editing & Design Thilo RISING (Newcastle) History of Classical Scholarship Issue () TABLE OF CONTENTS LORENZO CALVELLI, FEDERICO SANTANGELO A New Journal: Contents, Methods, Perspectives i–iv GERARD GONZÁLEZ GERMAIN Conrad Peutinger, Reader of Inscriptions: A Note on the Rediscovery of His Copy of the Epigrammata Antiquae Urbis (Rome, ) – GINETTE VAGENHEIM L’épitaphe comme exemplum virtutis dans les macrobies des Antichi eroi et huomini illustri de Pirro Ligorio ( c.–) – MASSIMILIANO DI FAZIO Gli Etruschi nella cultura popolare italiana del XIX secolo. Le indagini di Charles G. Leland – JUDITH P. HALLETT The Legacy of the Drunken Duchess: Grace Harriet Macurdy, Barbara McManus and Classics at Vassar College, – – LUCIANO CANFORA La lettera di Catilina: Norden, Marchesi, Syme – CHRISTOPHER STRAY The Glory and the Grandeur: John Clarke Stobart and the Defence of High Culture in a Democratic Age – ILSE HILBOLD Jules Marouzeau and L’Année philologique: The Genesis of a Reform in Classical Bibliography – BEN CARTLIDGE E.R. -

Concluding Common Joint Statement

Concluding Common Joint Statement of the Commission for the Dialogue between the Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church and the Old Catholic Churches of the Union of Utrecht Editorial Note: The sub-commission (Rev. Sam T. Koshy, Rev. Dr. Adrian Suter) has worked on this statement and considers this version to be the final one. Other than the correction of errors and the adaption of the reference style in the footnotes in case of a printed publication, no more changes shall be made. Introduction: A journey towards a relationship of communion between the Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church and the Old Catholic Churches of the Union of Utrecht The ecumenical journey between the two churches began with the meeting of Archbishop Dr. Joris Vercammen, President of the International Bishops’ Conference of the Old Catholic Churches of the Union of Utrecht, and Rt. Rev. Dr. Zacharias Mar Theophilus, then Suffragan Metropolitan (now of blessed memory), of the Mar Thoma Church in the context of the World Council of Churches, in 2005. Later, Rt. Rev. Dr. Isaac Mar Philoxenos Episcopa continued the contact with the Union of Utrecht. On the invitation of the Metropolitan of the Mar Thoma Church, a delegation from the Union of Utrecht, which included the Archbishop of Utrecht, 1 the bishop of the Old Catholic Church of Austria, Dr. John Okoro, the Rev. Prof. Günter Esser and the Rev. Ioan Jebelean, visited the Mar Thoma Church in 2006 and 2008. A delegation of the Mar Thoma Church made a reciprocal visit to the Old Catholic Church. The Rt. Rev. -

Traditional Dietary Culture of Southeast Asia

Traditional Dietary Culture of Southeast Asia Foodways can reveal the strongest and deepest traces of human history and culture, and this pioneering volume is a detailed study of the development of the traditional dietary culture of Southeast Asia from Laos and Vietnam to the Philippines and New Guinea from earliest times to the present. Being blessed with abundant natural resources, dietary culture in Southeast Asia flourished during the pre- European period on the basis of close relationships between the cultural spheres of India and China, only to undergo significant change during the rise of Islam and the age of European colonialism. What we think of as the Southeast Asian cuisine today is the result of the complex interplay of many factors over centuries. The work is supported by full geological, archaeological, biological and chemical data, and is based largely upon Southeast Asian sources which have not been available up until now. This is essential reading for anyone interested in culinary history, the anthropology of food, and in the complex history of Southeast Asia. Professor Akira Matsuyama graduated from the University of Tokyo. He later obtained a doctorate in Agriculture from that university, later becoming Director of Radiobiology at the Institute of Physical and Chemical research. After working in Indonesia he returned to Tokyo's University of Agriculture as Visiting Professor. He is currently Honorary Scientist at the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, Tokyo. This page intentionally left blank Traditional Dietary Culture of Southeast Asia Its Formation and Pedigree Akira Matsuyama Translated by Atsunobu Tomomatsu Routledge RTaylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published by Kegan Paul in 2003 This edition first published in 2009 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint o f the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2003 Kegan Paul All rights reserved. -

Indeed He Is Risen! Christ Is Risen!

Your Diocese Alive in Christ The Magazine of the Diocese of Eastern Pennsylvania, Orthodox Church in America Volume XXI, No. 1 Spring, 2005 Christ is Risen! Indeed He Is Risen! 1ooth Anniversary of St. Tikhon’s Monastery Plan now to organize a bus from your parish or group PASCHA Christ is Risen! Indeed He is Risen! 2005 To the Very Reverend and Reverend Clergy, Monastics, and Faithful of the Orthodox Church in America: Dearly Beloved in the Lord, nce again, we greet one another with these joyous words, words that not only embody the essence of our Paschal celebration, but embody the very essence of our faith and Ohope in the love of Our Lord. Central to our faith are the words of Saint Paul: “If Christ is not risen, our preaching is in vain and your faith is also in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14). Having desired to reconcile all creation to its Creator, the only-begotten Son of God took on our human fl esh. He entered human history, time, and space, as one of us. He came not to be served but, rather, to serve. And in so doing, He revealed that God “is not the God of the dead, but of the living” (Matthew 22:32), the God Who desired the renewal and transformation of His people and all creation with such intensity that He was willing to die, that life might reign. By His death and resurrection, He led us into a new promised land, one in which there is no sickness, sorrow, nor sighing, but life everlasting. -

7 Questions for Harri Wessman Dante Anarca

nHIGHLIGHTS o r d i c 3/2016 n EWSLETTE r F r o M G E H r MA n S M U S i KFÖ r L A G & F E n n i c A G E H r MA n 7 questions for Harri Wessman dante Anarca NEWS Rautavaara in memoriam Colourstrings licensed in China Fennica Gehrman has signed an agreement with the lead- Einojuhani Rautavaara died in Helsinki on 27 July at the age ing Chinese publisher, the People’s Music Publishing of 87. One of the most highly regarded and inter nationally House, on the licensing of the teaching material for the best-known Finnish com posers, he wrote eight symp- Colourstrings violin method in China. The agreement honies, vocal and choral works, chamber and instrumen- covers a long and extensive partnership over publication of tal music as well as numerous concertos, orchestral works the material and also includes plans for teacher training in and operas, the last of which was Rasputin (2001–03). China. The Colourstrings method developed byGéza and Rautavaara’s international breakthrough came with his Csaba Szilvay has spread far and wide in the world and 7th symphony, Angel of Light (1994) , when keen crit- is regarded as a first-class teaching method for stringed ics likened him to Sibelius. His best-beloved orchestral instruments. work is the Cantus arcticus for birds and orchestra, for which he personally recorded the sounds of the birds. Apart from being an acclaimed composer, Rautavaara had a fine intellect, was a mystical storyteller and had a masterly command of words. -

HISTORY of the NATIONAL CATHOLIC COMMITTEE for GIRL SCOUTS and CAMP FIRE by Virginia Reed

Revised 3/11/2019 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC COMMITTEE FOR GIRL SCOUTS AND CAMP FIRE By Virginia Reed The present National Catholic Committee for Girl Scouts and Camp Fire dates back to the early days of the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) and the National Catholic Welfare Conference. Although it has functioned in various capacities and under several different names, this committee's purpose has remained the same: to minister to the Catholic girls in Girl Scouts (at first) and Camp Fire (since 1973). Beginnings The relationship between Girl Scouting and Catholic youth ministry is the result of the foresight of Juliette Gordon Low. Soon after founding the Girl Scout movement in 1912, Low traveled to Baltimore to meet James Cardinal Gibbons and consult with him about her project. Five years later, Joseph Patrick Cardinal Hayes of New York appointed a representative to the Girl Scout National Board of Directors. The cardinal wanted to determine whether the Girl Scout program, which was so fine in theory, was equally sound in practice. Satisfied on this point, His Eminence publicly declared the program suitable for Catholic girls. In due course, the four U.S. Cardinals and the U.S. Catholic hierarchy followed suit. In the early 1920's, Girl Scout troops were formed in parochial schools and Catholic women eagerly became leaders in the program. When CYO was established in the early 1930's, Girl Scouting became its ally as a separate cooperative enterprise. In 1936, sociologist Father Edward Roberts Moore of Catholic charities, Archdiocese of New York, studied and approved the Girl Scout program because it was fitting for girls to beome "participating citizens in a modern, social democracy." This support further enhanced the relationship between the Catholic church and Girl Scouting. -

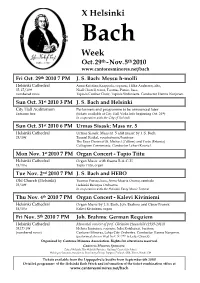

X Helsinki Week

X Helsinki Bach Week th th Oct. 29 - Nov. 5 2010 www.cantoresminores.net/bach Fri Oct. 29th 2010 7 PM J. S. Bach: Messu h-molli Helsinki Cathedral Anna-Kristiina Kaappola, soprano, Hilke Andersen, alto, 35, 17/10 € Niall Chorell, tenor, Tuomas Pursio, bass, numbered rows Tapiola Camber Choir, Tapiola Sinfonietta. Conductor Hannu Norjanen. Sun Oct. 31st 2010 3 PM J. S. Bach and Helsinki City Hall Auditorium Performers and programme to be announced later Entrance free (tickets available at City Hall Virka Info beginning Oct. 24th) In cooperation with the City of Helsinki Sun Oct. 31st 2010 6 PM Urmas Sisask: Mass nr. 5 Helsinki Cathedral Urmas Sisask: Mass nr. 5 and music by J. S. Bach 25/10€ Taaniel Kirikal, countertenor/baritone The Boys Choirs of St. Michael (Tallinn) and Tarto (Estonia) Collegium Consonante. Conductor Lehari Kaustel. Mon Nov. 1st 2010 7 PM Organ Concert - Tapio Tiitu Helsinki Cathedral Organ Music with theme B-A-C-H 15/10 e Tapio Tiitu, organ Tue Nov. 2nd 2010 7 PM J. S. Bach and HEBO Old Church (Helsinki) Tuomas Pursio, bass, Anna-Maaria Oramo, cembalo 25/10€ Helsinki Baroque Orchestra In cooperation with the Helsinki Early Music Festival Thu Nov. 4th 2010 7 PM Organ Concert - Kalevi Kiviniemi Helsinki Cathedral Organ Music by J. S. Bach, Joh. Brahms and César Franck 15/10 e Kalevi Kiviniemi, organ Fri Nov. 5th 2010 7 PM Joh. Brahms: German Requiem Helsinki Cathedral Memorial concert of prof. Christian Hauschild (1939-2010) 35,17/10€ Helena Juntunen, soprano, Juha Kotilainen, baritone (numbered rows) Cantores Minores, Lohja City Orchestra.