Unit 4 Folk Forms As Protest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IJRESS Volume 6, Issue 2

International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences (IJRESS) Available online at: http://euroasiapub.org Vol. 7 Issue 7, July- 2017 ISSN(o): 2249-7382 | Impact Factor: 6.939 | Thomson Reuters Researcher ID: L-5236-2015 Dissemination of social messages by Folk Media – A case study through folk drama Bolan of West Bengal Mr. Sudipta Paul Research Scholar, Department of Mass Communication & Videography, Rabindra Bharati University Abstract: In the vicinity of folk-culture, folk drama is of great significance because it reflects the society by maintaining a non-judgemental stance. It has a strong impact among the audience as the appeal of Bengali folk-drama is undeniable. ‘Bolan’ is a traditional folk drama of Bengal which is mainly celebrated in the month of ‘Chaitra’ (march-april). Geographically, it is prevalent in the mid- northern rural and semi-urban regions of Bengal (Rar Banga area) – mainly in Murshidabad district and some parts of Nadia, Birbhum and Bardwan districts. Although it follows the theatrical procedures, yet it is different from the same because it has no female artists. The male actors impersonate as females and play the part. Like other folk drama ‘Bolan’ is in direct contact with the audience and is often interacted and modified by them. Primarily it narrates mythological themes but now-a-days it narrates contemporary socio-politico-economical and natural issues. As it is performed different contemporary issues of immense interest audiences is deeply integrated with it and try to assimilate the messages of social importance from it. And in this way Mass (traditional) media plays an important role in shaping public opinion and forming a platform of exchange between the administration and the people they serve. -

THE DEVELOPMENT TEAM Principal Investigator Prof. S. P. Bansal Vice

Paper 11: Special Interest Tourism Module 34: Performing Arts of India: Classical Dances, Folk Dance & HistoricalFolk Culture Development of Tourism and Hospitality in the World THE DEVELOPMENT TEAM Principal Investigator Prof. S. P. Bansal Vice Chancellor, Indira Gandhi University, Rewari Co-Principal Investigator Dr. Prashant K. Gautam Director, UIHTM, Panjab University, Chandigarh Paper Coordinator Prof. Deepak Raj Gupta School of Hospitality & Tourism Management (SHTM), Jammu University Content Writer Dr. Arunesh parashar, Chief Coordinator Department Of Tourism Management, Dev Sanskriti University Content Reviewer Prof. Pariskhit Manhas Director , school of hospitality & tourism management Jammu university, Jammu ITEMS DESCRIPTION OF MODULE Subject Name Tourism and Hotel Management Paper Name Special Interest Tourism Module Title Performing Arts of India: Classical Dances, Folk Dances and Folk Culture Module Id 34 Pre- Requisites Basic knowledge about Performing Arts Objectives To develop a basic insight about the performing arts in India Keywords Classical, folks lore, folk dances and folk cultures QUADRANT-I Performing arts are divided into two dimensions of performance: Dance Music Classical dance Bharatnatyam Bharatnatyam originates in Tamil Nadu which is likewise alluded to as artistic yoga and Natya yoga. The name Bharatnatyam is gotten from the word "Bharata’s" and subsequently connected with the Natyashashtra. Though the style of Bharatnatyam is over two thousand years old, the freshness and lavishness of its embodiment has been held even today. The strategy of human development which Bharatnatyam takes after can be followed back to the fifth Century A.D. from sculptural proof. This established move has an entrancing impact as it inspires the artist and the spectator to a larger amount of profound cognizance. -

Wedding Videos

P1: IML/IKJ P2: IML/IKJ QC: IML/TKJ T1: IML PB199A-20 Claus/6343F August 21, 2002 16:35 Char Count= 0 WEDDING VIDEOS band, the blaring recorded music of a loudspeaker, the References cries and shrieks of children, and the conversations of Archer, William. 1985. Songs for the bride: wedding rites of adults. rural India. New York: Columbia University Press. Most wedding songs are textually and musically Henry, Edward O. 1988. Chant the names of God: musical cul- repetitive. Lines of text are usually repeated twice, en- ture in Bhojpuri-Speaking India. San Diego: San Diego State abling other women who may not know the song to University Press. join in. The text may also be repeated again and again, Narayan, Kirin. 1986. Birds on a branch: girlfriends and wedding songs in Kangra. Ethos 14: 47–75. each time inserting a different keyword into the same Raheja, Gloria, and Ann Gold. 1994. Listen to the heron’s words: slot. For example, in a slot for relatives, a wedding song reimagining gender and kinship in North India. Berkeley: may be repeated to include father and mother, father’s University of California Press. elder brother and his wife, the father’s younger brother and his wife, the mother’s brother and his wife, paternal KIRIN NARAYAN grandfather and grandmother, brother and sister-in-law, sister and brother-in-law, and so on. Alternately, in a slot for objects, one may hear about the groom’s tinsel WEDDING VIDEOS crown, his shoes, watch, handkerchief, socks, and so on. Wedding videos are fast becoming the most com- Thus, songs can be expanded or contracted, adapting to mon locally produced representation of social life in the performers’ interest or the length of a particular South Asia. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Minutes of 32Nd Meeting of the Cultural

1 F.No. 9-1/2016-S&F Government of India Ministry of Culture **** Puratatav Bhavan, 2nd Floor ‘D’ Block, GPO Complex, INA, New Delhi-110023 Dated: 30.11.2016 MINUTES OF 32nd MEETING OF CULTURAL FUNCTIONS AND PRODUCTION GRANT SCHEME (CFPGS) HELD ON 7TH AND 8TH MAY, 2016 (INDIVIDUALS CAPACITY) and 26TH TO 28TH AUGUST, 2016 AT NCZCC, ALLAHABAD Under CFPGS Scheme Financial Assistance is given to ‘Not-for-Profit’ Organisations, NGOs includ ing Soc iet ies, T rust, Univ ersit ies and Ind iv id ua ls for ho ld ing Conferences, Seminar, Workshops, Festivals, Exhibitions, Production of Dance, Drama-Theatre, Music and undertaking small research projects etc. on any art forms/important cultural matters relating to different aspects of Indian Culture. The quantum of assistance is restricted to 75% of the project cost subject to maximum of Rs. 5 Lakhs per project as recommend by the Expert Committee. In exceptional circumstances Financial Assistance may be given upto Rs. 20 Lakhs with the approval of Hon’ble Minister of Culture. CASE – I: 1. A meeting of CFPGS was held on 7 th and 8th May, 2016 under the Chairmanship of Shri K. K. Mittal, Additional Secretary to consider the individual proposals for financial assistance by the Expert Committee. 2. The Expert Committee meeting was attended by the following:- (i) Shri K.K. Mittal, Additional Secretary, Chairman (ii) Shri M.L. Srivastava, Joint Secretary, Member (iii) Shri G.K. Bansal, Director, NCZCC, Allahabad, Member (iv ) Dr. Om Prakash Bharti, Director, EZCC, Kolkata, Member, (v) Dr. Sajith E.N., Director, SZCC, Thanjavur, Member (v i) Shri Babu Rajan, DS , Sahitya Akademi , Member (v ii) Shri Santanu Bose, Dean, NSD, Member (viii) Shri Rajesh Sharma, Supervisor, LKA, Member (ix ) Shri Pradeep Kumar, Director, MOC, Member- Secretary 3. -

Cultural Filigree

Cultural Filigree By Riffat Farjana ID: 10308018 Seminar II Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Bachelor of Architecture Department of Architecture BRAC University " — । , , — । ? - । । " ----------- Abstract Abstract " , । । , " ---- The project has been developed by connecting different urban cultural corridors by bringing the life and energy into the center of the city Bogra by making the 100 years old park more greener and more accommodating by active and passive participation of the users. The project can be described as a "PAST in the FUTURE" , a proper balance between nature and culture. The project is a raw interface between building and landscape where people and plan co-exist and can share the same surface at the same time creates a clear system of interaction between nature and the city. The project provides an opportunity to level the city at the same time be more closer to it. where the nature provides an unexpected contrast to the city keeping balance with the culture. Acknowledgement Acknowledgement I would like to begin by thanking almighty Allah for his mercy and for fulfilling all my wishes in life. All the grace to Allah for everything I have achieved till now. Again, I am thankful to Almighty for blessing me with a beautiful life with some people, who always guide me when I needed most ,in the form of my Abbu and Ammu to whom I am always thankful for their support , sacrifices and blessings , in the form of my Nanu (late Dr. Nurul Islam Chowdhury) to whom I am thankful for his blessings and for always being proud of me, even in times, when I didn‘t deserve such faith. -

State Dance (S) Andra Pradesh Kuchipudi, Kolattam, Ghantamardala, (Ottam Thedal, Mohiniattam, Kummi, Siddhi, Madhuri, Chhadi

BHARAT SCHOOL OF BANKING STATIC GK Indian Cultural/Classical Dances - Folk Dances in India State Dance (S) Andra Pradesh Kuchipudi, Kolattam, Ghantamardala, (Ottam Thedal, Mohiniattam, Kummi, Siddhi, Madhuri, Chhadi. Arunachal Pradesh Bardo Chham Assam Bihu, Ali Ai Ligang, Bichhua, Natpuja, Maharas, Kaligopal, Bagurumba, Naga dance, Khel Gopal, Tabal Chongli, Canoe, Jhumura Hobjanai etc. Bihar Chhau,Jata-Jatin, Bakho-Bakhain, Panwariya, Sama-Chakwa, Bidesia, Jatra etc. Chhattisgarh Panthi, Raut Nacha, Gaur Maria, Goudi, Karma, Jhumar, Dagla, Pali, Tapali, Navrani, Diwari, Mundari. Goa Tarangamel, Dashavatara, Dekhni, Dhalo, Dhangar, Fugdi, Ghodemodni, Goff, Jagar, Kunbi, Mando, Musal Khel, Perni Jagar, Ranamale, Romta Mel, Divlyan Nach (Lamp dance), Veerabhadra, Morulo, Tonayamel , Mandi, Jhagor, Khol, Dakni, , Koli Gujarat Garba, Dandiya Ras, Tippani Juriun, Bhavai. Haryana Saang, Chhathi, Khoria, Ras Leela, Dhamal, Jhumar, Loor, Gugga, Teej Dance, Phag, Daph, Gagor Himachal Pradesh Kinnauri, Mangen, Jhora, Jhali, Chharhi, Dhaman, Chhapeli, Mahasu, Nati, Dangi, Chamba, Thali, Jhainta, Daf, Stick dance Jammu & Kashmir Kud, Dumhal, Rauf, Hikat, Mandjas, Damali Jharkhand Chhanu, Sarahul, Jat-Jatin, Karma , Munda, Danga, Bidesia, Sohrai. Karnataka Yakshagan, Bayalatta, Dollu Kunitha, Veeragasse, Huttar, Suggi, Kunitha, Karga, Lambi Kerala Mohiniyattam, Kathakali, Thirayattam, Theyyam, Thullal, Koodiyattam, Duffmuttu / Aravanmuttu, Oppana, Kaikottikali, Thiruvathirakali, Margamkali, Thitambu Nritham, Chakyar Koothu, Chavittu Nadakam, Padayani -

Background Material on Service Tax- Entertainment Sector

Background Material on Service Tax- Entertainment Sector The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (Set up by an Act of Parliament) New Delhi © The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission, in writing, from the publisher. DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this book are of the author(s). The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India may not necessarily subscribe to the views expressed by the author(s). The information cited in this book has been drawn from various sources. While every effort has been made to keep the information cited in this book error free, the Institute or any office of the same does not take the responsibility for any typographical or clerical error which may have crept in while compiling the information provided in this book. Edition : February, 2015 Committee/Department : Indirect Taxes Committee Email : [email protected] Website : www.idtc.icai.org Price : ` 90/- ISBN No. : 978-81-8441-759-3 Published by : The Publication Department on behalf of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, ICAI Bhawan, Post Box No. 7100, Indraprastha Marg, New Delhi - 110 002. Printed by : Sahitya Bhawan Publications, Hospital Road, Agra 282 003 February/2015/1,000 Foreword The introduction of Service Tax was recommended by Dr. Raja Chelliah Committee in early 1990s which pointed out that the indirect taxes at the Central level should be broadly neutral in relation to production and consumption of goods and should, in course of time cover commodities and services. -

Unit 14 Art and Music

English One Unit 14 Art and Music Objective: After the completion of this unit, you will − • read and understand poems. • ask and answer questions. • summarise literary texts. Overview: Lesson 1: What is Beauty? Lesson 2: Folk Music Lesson 3: Crafts in Our Time Answer Key Unit-14 Page # 207 HSC Programme Lesson 1 : What is Beauty? 1. Warm-up activity: • In a group, discuss what you mean by beauty; and its place in art. • Discuss any work of art you have seen (a painting, a sculpture, a photograph, an embroidered quilt and why you consider it beautiful). Beauty is easy to appreciate but difficult to define. As we look around, we discover beauty in pleasurable objects and sights - in nature, in the laughter of children, in the kindness of strangers. But asked to define, we run into difficulties. Does beauty have an independent objective identity? Is it universal, or is it dependent on our sense perceptions? Does it lie in the eye of the beholder? -we ask ourselves. A further difficulty arises when beauty manifests itself not only by its presence, but by its absence as well, as when we are repulsed by ugliness and desire beauty. But then ugliness has as much a place in our lives as beauty, or may be more-as when there is widespread hunger and injustice in a society. Philosophers have told us that beauty is an important part of life, but isn't ugliness a part of life too? And if art has beauty as an important ingredient, can it confine itself only to a projection of beauty? Can art ignore what is not beautiful? Poets and artists have provided an answer by incorporating both into their work. -

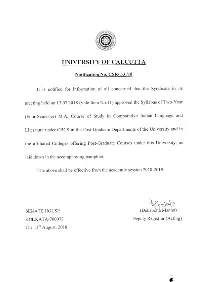

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR 1. Title and Commencement: 1.1 These Regulations shall be called THE REGULATIONS FOR SEMESTERISED M.A. in Comparative Indian Language and Literature Post- Graduate Programme (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) 2018, UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA. 1.2 These Regulations shall come into force with effect from the academic session 2018-2019. 2. Duration of the Programme: The 2-year M.A. programme shall be for a minimum duration of Four (04) consecutive semesters of six months each/ i.e., two (2) years and will start ordinarily in the month of July of each year. 3. Applicability of the New Regulations: These new regulations shall be applicable to: a) The students taking admission to the M.A. Course in the academic session 2018-19 b) The students admitted in earlier sessions but did not enrol for M.A. Part I Examinations up to 2018 c) The students admitted in earlier sessions and enrolled for Part I Examinations but did not appear in Part I Examinations up to 2018. d) The students admitted in earlier sessions and appeared in M.A. Part I Examinations in 2018 or earlier shall continue to be guided by the existing Regulations of Annual System. 4. Attendance 4.1 A student attending at least 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. 4.2 A student attending at least 60% but less than 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to the payment of prescribed condonation fees and fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. -

Social, Economic and Political Transition of a Bengal District : Malda 1876-1953

SOCIAL, ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL TRANSITION OF A BENGAL DISTRICT : MALDA 1876-1953 Thesis submitted to the University of North Bengal for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in i-iistory ASHIM KUMAR SARKAR Lecturer In History Malda College, Malda Sufmrvisor Ananda Giipal Ghosh Professor Department of History University of North Bengal UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2010 954-14 asi-/r^ '-'cr-^i,;, CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled Social, Economic and Political Transition of a Bengal District: Malda 1876-1953 embodies the result of original and bonafide research work done by Sri Ashim Kumar Sarkar under my supervision. Neither this thesis nor any part of it has been submitted for any degree or any other academic awards anywhere before. Sri Sarkar has fulfilled all the requirements prescribed in the Ph.D. Ordinance of the University of North Bengal. I am pleased to fon^rd the thesis for submission to the University of North Bengal for the Degree of Doctor of Phitosophy (Ph.D.) in Arts. Date : i%-^ • ^• AnandaGopalGhosh Place : University of North Bengal Professor Department of History University of North Bengal DECLARATION I do hereby declare that the content in the thesis entitled Social, Economic and Political Transition of a Bengal District: Malda 1876-1953 is the outcome of my own research work done under the guidance and supervision of Professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh, Department of History, University of North Bengal. To the best of my knowledge, the sources in this thesis are authentic. This thesis has submitted neither simultaneously nor before either as such or part of it anywhere for any other degree or academic awards. -

Dance in India Dance Is a Product of Society and While Interacting with It Can Trace Its Roots to Several Centuries

PRELIMS SAMPOORNA As IAS prelims 2021 is knocking at the door, jitters and anxiety is a common emotion that an aspirant feels. But if we analyze the whole journey, these last few days act most crucial in your preparation. This is the time when one should muster all their strength and give the fi nal punch required to clear this exam. But the main task here is to consolidate the various resources that an aspirant is referring to. GS SCORE brings to you, Prelims Sampoorna, a series of all value-added resources in your prelims preparation, which will be your one-stop solution and will help in reducing your anxiety and boost your confi dence. As the name suggests, Prelims Sampoorna is a holistic program, which has 360- degree coverage of high-relevance topics. It is an outcome-driven initiative that not only gives you downloads of all resources which you need to summarize your preparation but also provides you with All India open prelims mock tests series in order to assess your learning. Let us summarize this initiative, which will include: GS Score UPSC Prelims 2021 Yearly Current Affairs Compilation of All 9 Subjects Topic-wise Prelims Fact Files (Approx. 40) Geography Through Maps (6 Themes) Map Based Questions ALL India Open Prelims Mock Tests Series including 10 Tests Compilation of Previous Year Questions with Detailed Explanation We will be uploading all the resources on a regular basis till your prelims exam. To get the maximum benefi t of the initiative keep visiting the website. To receive all updates through notifi cation, subscribe: www.iasscore.in IAS 2021 | ART & CULTURE (DANCES OF INDIA) | 1 DANCES OF INDIA Dance is an expression of self and emotion.