Geography, Landscape and Mills Introduction Watermills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION Qadar Bakhsh Baloch

Qadar Bakhsh Baloch The Dialogue THE ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION Qadar Bakhsh Baloch “Thus we have appointed you a mid-most nation, that you may be witnesses upon mankind.” (Quran, 11:43) ISLAM WAS DESTINED to be a world religion and a civilisation, stretched from one end of the globe to the other. The early Muslim caliphates (empires), first the Arabs, then the Persians and later the Turks set about to create classical Islamic civilisation. In the 13th century, both Africa and India became great centres of Islamic civilisation. Soon after, Muslim kingdoms were established in the Malay-Indonesian world, while Muslims flourished equally in China. Islamic civilisation is committed to two basic principles: oneness of God and oneness of humanity. Islam does not allow any racial, linguistic or ethnic discrimination; it stands for universal humanism. Besides Islam have some peculiar features that distinguish it form other cotemporary civilisations. SALIENT FEATURES OF ISLAMIC CIVILISATION MAIN CHARACTERISTICS that distinguish Islamic civilisation from other civilisations and give it a unique position can be discerned as: • It is based on the Islamic faith. It is monotheistic, based on the belief in the oneness of the Almighty Allah, the Creator of this universe. It is characterised by submission to the will God and service to humankind. It is a socio-moral and metaphysical view of the world, which has indeed contributed immensely to the rise and richness of this civilisation. The author is a Ph. D. Research Scholar, Department of International Relations, University of Peshawar, N.W.F.P. Pakistan, the Additional Registrar of Qurtuba University and Editor of The Dialogue. -

In and Around the Watermill

In and around the watermill Our beautiful and historic watermill stands beside the River Rosaro in the small village of Posara. Peaceful and secluded, yet part of the village, the mill is just a mile or so from the walled medieval town of Fivizzano with its cafés, restaurants and shops. This is the heart of Lunigiana, in the North-west of Tuscany, a truly unspoilt part of Italy. Set in a gentle valley with mountain peaks in the background, the mill is a peaceful spot, surrounded by the National Park of the Tuscan-Emilian Appennines and The Regional Pak of the Apuan Alps, home of the marble mountains of Carrara. The Watermill is a complex of elegant and historic Tuscan buildings, around a sunny courtyard with an adjoining vine verandah, rose pergola and sun-filled walled garden. More gardens lead to walks along the river and the sun-dappled millstream. We have lovingly restored the historic buildings and created eight beautiful bedrooms with en suite bathrooms, plus two self-contained apartment suites, each with a double bedroom, bathroom and sitting room, ideal for couple or friends sharing. The bright and airy rooms are well decorated and tastefully furnished. Many contain original artworks and all enjoy lovely views of the river, the gardens or the mountains. Our graceful communal Sitting Room, with its gallery of paintings by our inspiring tutors, is ideal for post-prandial conversation and digestivi. Our courtyard dining room is the unique setting for leisurely breakfasts and mouth-watering evening meals. There is also a communal kitchen, with chilled water and facilities for personal tea-/coffee-making. -

Developments in Permanent Stainless Steel Cathodes Within the Copper Industry

DEVELOPMENTS IN PERMANENT STAINLESS STEEL CATHODES WITHIN THE COPPER INDUSTRY K.L. Eastwood and G.W. Whebell Xstrata Technology Hunter Street Townsville, Australia 4811 [email protected] ABSTRACT The ISA PROCESS™ cathode plate is characterised by its copper coated suspension bar, coupled with a blade employing austenitic stainless steel alloy 316L. The blade material has become the mainstay of the technology and has been closely copied by competing cathode designs. Improvement to the cathode plate design remains a key area for research, and ongoing developments by Xstrata Technology’s ISA PROCESS™ have recently been commercialised. Two such developments are the ISA Cathode BR™ and ISA 2000 AB Cathode. The ISA BR cathode is a lower resistance cathode that has proven to enhance operating efficiencies. The AB cathode was designed to improve stripping inefficiencies in the ISA 2000 technology. These developments have now had time to mature and their long term performance will be discussed. Rising material costs and the desire to extend the operating boundaries of the standard 316L cathode plate has triggered a number of significant advances. These involve the use of different stainless steels as alternatives in some operational situations. The technical aspects and results of commercial trials on this development will also be discussed in this paper. INTRODUCTION The introduction of permanent stainless steel cathode technology was pioneered in the copper industry by IJ Perry and colleagues in 1978, with the introduction of the ISA PROCESSTM in the Townsville Copper Refinery, Perry [1]. While a number of parallel processes have emerged since its introduction, ISA Process Technology (IPT) has continued to be the mainstay electrolytic copper process with consistent improvements and superior operational performance. -

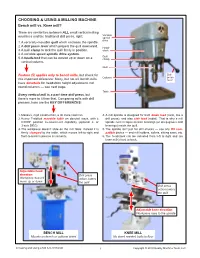

Choosing & Using a Milling Machine

CHOOSING & USING A MILLING MACHINE Bench mill vs. Knee mill? There are similarities between ALL small vertical milling Variable machines and the traditional drill press, right: speed drive 1. A vertically-movable quill which encloses the spindle. 2. A drill press lever which propels the quill downward. Head- 3. A quill clamp to lock the quill firmly in position. stock 4. A variable-speed spindle drive system. Quill 5. A headstock that can be moved up or down on a clamp vertical column. Quill Feature (5) applies only to bench mills, but check for Drill Column press this important difference: Many, but not all, bench mills lever have dovetails for headstock height adjustment, not round columns — see next page. Table Every vertical mill is a part-time drill press, but there’s more to it than that. Comparing mills with drill presses, here are the KEY DIFFERENCES: 1. Massive, rigid construction, a lot more cast iron. 4. A mill spindle is designed for both down load (axial, like a 2. Heavy T-slotted movable table on dovetail ways, with ± drill press), and also side load (radial). That is why a mill 0.0005″ position measurement capability (optional 2- or spindle runs in tapered roller bearings (or deep-groove ball 3-axis DRO). bearings) inside the quill. 3. The workpiece doesn’t slide on the mill table: instead it is 5. The spindle isn’t just for drill chucks — use any R8 com- firmly clamped to the table, which moves left-to-right and patible device — end mill holders, collets, slitting saws, etc. -

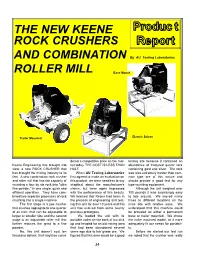

THE NEW KEENE ROCK CRUSHERS ROLLER MILL Produc T Report

THE NEW KEENE Produc t ROCK CRUSHERS Report AND COMBINATION By AU Testing Laboratories ROLLER MILL Base Mount Trailer Mounted Electric Driven dered a competitive price on the mar- testing site because it contained an Keene Engineering has brought into ket today. THE COST IS LESS THAN abundance of fractured quartz rock view, a new ROCK CRUSHER that HALF. containing gold and silver. The rock has brought the mining industry to its When AU Testing Laboratories was also extremely harder than com- feet. A new combination rock crusher first agreed to make an evaluation on mon type ore of this nature and and roller mill that has the capacity of this product, we were needless to say should provide a good test for any crushing a four by six rock into "ultra skeptical about the manufacturer's type crushing equipment. fine powder," in one single, quick and claims, but were again impressed Although the unit weighed over efficient operation. They have com- with the performance of this beauty. 700 pounds it was surprisingly easy bined two separate processes of rock We learned that Keene had been in to tote around. We moved many crushing into a single machine. the process of engineering and test- times to different locations on the The first stage is a jaw crusher ing this unit for over 10 years and this mine site with relative ease. We that crushes aggregate to one quarter unit has evolved from some twenty understood that this machine could of an inch, that can be adjustable to previous prototypes. be provided on either a permanent larger or smaller size and the second We loaded the unit with its base or trailer mounted. -

Milling Studies in an Impact Crusher I: Kinetics Modelling Based on Population Balance Modelling

minerals Article Milling Studies in an Impact Crusher I: Kinetics Modelling Based on Population Balance Modelling Ngonidzashe Chimwani 1,* and Murray M. Bwalya 2 1 Institute of the Development of Energy for African Sustainability (IDEAS), Florida Campus, University of South Africa (UNISA), Private Bag X6, Johannesburg 1710, South Africa 2 School of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2050, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-731838174 Abstract: A number of experiments were conducted on a laboratory batch impact crusher to investi- gate the effects of particle size and impeller speed on grinding rate and product size distribution. The experiments involved feeding a fixed mass of particles through a funnel into the crusher up to four times, and monitoring the grinding achieved with each pass. The duration of each pass was approximately 20 s; thus, this amounted to a total time of 1 min and 20 s of grinding for four passes. The population balance model (PBM) was then used to describe the breakage process, and its effectiveness as a tool for describing the breakage process in the vertical impact crusher is assessed. It was observed that low impeller speeds require longer crushing time to break the particles significantly whilst for higher speeds, longer crushing time is not desirable as grinding rate sharply decreases as the crushing time increases, hence the process becomes inefficient. Results also showed that larger particle sizes require shorter breakage time whilst smaller feed particles require longer breakage time. Keywords: impact crusher; comminution; milling parameters; population balance mode Citation: Chimwani, N.; Bwalya, M.M. -

Energy Consumption in Italy 1861-2000 93 2

Energy Consumption in Italy in the 19th and 20th Centuries A Statistical Outline by Paolo Malanima Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Istituto di Studi sulle Società del Mediterraneo Elaborazione ed impaginazione a cura di: Aniello Barone e Paolo Pironti ISBN 88-8080-066-3 Copyright © 2006 by Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), Istituto di Studi sulle Società del Mediterraneo (ISSM). Tutti i diritti sono riservati. Nessuna parte di questa pubblicazione può essere fotocopiata, riprodotta, archiviata, memorizzata o trasmessa in qualsiasi forma o mezzo – elettronico, meccanico, reprografico, digitale – se non nei termini previsti dalla legge che tutela il Diritto d’Autore. INDEX Foreword 5 1. Energy sources 7 1.1. The energy transition 9 1.2. Definitions 10 1.3. Primary sources 13 1.4. Territory and population 15 2. Traditional sources 19 2.1. Methods 21 2.2. Food 26 2.3. Firewood 28 2.4. Animals 34 2.5. Wind 36 2.6. Water 37 2.7. Consumption of traditional sources 42 3. Modern sources 45 3.1. From traditional to modern energy carriers 47 3.2. Fossil sources 54 3.3. Primary electricity 58 3.4. Consumption of modern sources 62 4. Energy and product 67 4.1. The trend 69 4.2. Energy intensity and productivity of energy 72 4.3. Conclusion 78 4 Index List of abbreviations 79 References 81 Appendix 89 I Aggregate series 91 1. Energy consumption in Italy 1861-2000 93 2. The structure of energy consumption 1861- 2000 96 3. Per capita energy consumption 1861-2000 99 II The energy carriers 103 1. -

Avoiding Slopping in Top-Blown BOS Vessels

ISSN: 1402-1757 ISBN 978-91-7439-XXX-X Se i listan och fyll i siffror där kryssen är LICENTIATE T H E SI S Department of Chemical Engineering and Geosciences Division of Extractive Metallurgy Mats Brämming Avoiding Slopping in Top-Blown BOS Vessels BOS Top-Blown Slopping in Mats Brämming Avoiding ISSN: 1402-1757 ISBN 978-91-7439-173-2 Avoiding Slopping Luleå University of Technology 2010 in Top-Blown BOS Vessels Mats Brämming Avoiding Slopping in Top-blown BOS Vessels Mats Brämming Licentiate Thesis Luleå University of Technology Department of Chemical Engineering and Geosciences Division of Extractive Metallurgy SE-971 87 Luleå Sweden 2010 Printed by Universitetstryckeriet, Luleå 2010 ISSN: 1402-1757 ISBN 978-91-7439-173-2 Luleå 2010 www.ltu.se To my fellow researchers: “Half a league half a league, Half a league onward, All in the valley of Death Rode the six hundred: 'Forward, the Light Brigade! Charge for the guns' he said: Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred. 'Forward, the Light Brigade!' Was there a man dismay'd ? Not tho' the soldier knew Some one had blunder'd: Theirs not to make reply, Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to do & die, Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred.” opening verses of the poem “The Charge Of The Light Brigade” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson PREFACE Slopping* is the technical term used in steelmaking to describe the event when the slag foam cannot be contained within the process vessel, but is forced out through its opening. This phenomenon is especially frequent in a top-blown Basic Oxygen Steelmaking (BOS) vessel, i.e. -

Working with Watermills" Lesson Explores How Watermills Have Helped Harness Energy from Water Through the Ages

IEEE Lesson Plan: W or k i ng w i t h W at e r m i ll s Explore other TryEngineering lessons at www.tryengineering.org Lesson Focus Lesson focuses on how watermills generate power. Student teams design and build a working watermill out of everyday products and test their design in a basin. Student watermills must be able to sustain three minutes of rotation. As an extension activity, older students may design a gear system that is powered by the watermill. Students then evaluate the effectiveness of their watermill and those of other teams, and present their findings to the class. Lesson Synopsis The "Working with Watermills" lesson explores how watermills have helped harness energy from water through the ages. Students work in teams of "engineers" to design and build their own watermill out of everyday items. They test their watermill, evaluate their results, and present to the class. A g e L e v e l s 8-18. Objectives Learn about engineering design. Learn about planning and construction. Learn about teamwork and working in groups. Anticipated Learner Outcomes As a result of this activity, students should develop an understanding of: structural engineering and design problem solving teamwork Lesson Activities Students learn how watermills have been used throughout the ages to harness the power of water. Students work in teams to develop a their own watermill out of everyday items, then test their watermill, evaluate their own watermills and those of other students, and present their findings to the class. Working with Watermills Provided by IEEE as part of TryEngineering www.tryengineering.org © 2018 IEEE – All rights reserved. -

WATER MILL Working, Metal Working, Textiles Carding, Discharge: 70-150 Lps Areas

Day time (approx 40% load) SPECIFICATIONS OF MPPU FOR A ABOUT AHEC Alternate Hydro Energy Centre (AHEC) was set TYPICAL SITE up at Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee (formerly Increased milling capacity, oil expelling, rice University of Roorkee) by the Ministry of Non- hulling, spice-hulling, processing of dairy and Site Details: Conventional Energy Sources (MNES), Govt. of India, food products, workshop machines : wood in the year 1982 to promote power generation through Head: 7.0-15.0 m the development of small hydro in hilly as well as in plain WATER MILL working, metal working, textiles carding, Discharge: 70-150 lps areas. AHEC offers a variety of services in the field of commercial cooking etc. small hydro power development and other Power developed: upto 10.0 kW interdisciplinary areas. Small Hydro Power Evening time (approx 20% load) * Refurbishment, renovation and modernisation of SHP stations. * Detailed project reports, engineering designs and Electricity generation : lighting, cooking construction drawings. * Technical specifications. Night time (approx 40% load) * Pre-feasibility reports. * Planning, designs and execution. * Techno-economic appraisal. Electricity generation : lighting, battery * Monitoring of projects. charging. * Remote sensing and GIS based applications. Other Fields Heating for : drying, house heating, horticultural * Power system planning and operation. glass houses, hot water for washing, for laundry, LAYOUT OF A TYPICAL MPPU SITE * Energy Auditing. Details of Machine : * Drainage/irrigation related projects. cooking water, fish farming, chick rearing. * Environment impact assessment and Ecorestoration. Cold storage for : crops for sale, produce from Turbine * R&D in the field of other renewable energy sources traders. Type of turbine: Open Cross Flow (Solar, Biomass, Wind etc.) Runner dia: 300 mm Human Resources Development Pumping water : irrigation, drinking. -

Hydropower Vision Chapter 2

Chapter 2: State of Hydropower in the United States Hydropower A New Chapter for America’s Renewable Electricity Source STATE OF HYDROPOWER 2 in the United States Photo from 65681751. Illustration by Joshua Bauer/NREL 70 2 Overview OVERVIEW Hydropower is the primary source of renewable energy generation in the United States, delivering 48% of total renewable electricity sector generation in 2015, and roughly 62% of total cumulative renewable generation over the past decade (2006-2015) [1]. The approximately 101 gigawatts1 (GW) of hydropower capacity installed as of 2014 included ~79.6 GW from hydropower gener ation2 facilities and ~21.6 GW from pumped storage hydro- power3 facilities [2]. Reliable generation and grid support services from hydropower help meet the nation’s require- ments for the electrical bulk power system, and hydro- power pro vides a long-term, renewable source of energy that is essentially free of hazardous waste and is low in carbon emissions. Hydropower also supports national energy security, as its fuel supply is largely domestic. % 48 HYDROPOWER PUMPED CAPACITY STORAGE OF TOTAL CAPACITY RENEWABLE GENERATION Hydropower is the largest renewable energy resource in the United States and has been an esta blished, reliable contributor to the nation’s supply of elec tricity for more than 100 years. In the early 20th century, the environmental conse- quences of hydropower were not well characterized, in part because national priorities were focused on economic development and national defense. By the latter half of the 20th century, however, there was greater awareness of the environmental impacts of dams, reservoirs, and hydropower operations. -

Palaeo-Environmental Condition Factor on the Diffusion of Ancient Water Technologies

Gül Sürmelihindi Palaeo-Environmental Condition Factor on the Diffusion of Ancient Water Technologies Summary Thales of Miletus wisely declared that water is the vital element for life. Being the core sub- stance for human survival, the management of water has always been an important mat- ter. Early attempts to improve water-lifting devices for agricultural endeavors have been detected in Hellenistic Alexandria. However, aside from the limitations of the different de- vices, variations in geology also limit the use of some of these machines in specific areas. Some of these devices were used daily, whereas others remained impractical or were of mi- nor importance due to their complicated nature, and some were even forgotten until they were later rediscovered. Water also became a basic power source, providing energy, e.g. for cutting stone or milling grain, and such applications constituted the first attempts at Roman industrialization. Keywords: ancient water technologies; Hellenistic science; diffusion; geology; geography; Roman; aqueduct Bereits Thales von Milet erklärte Wasser zum wichtigsten Element allen Lebens. Entspre- chend kam dem Management dieser Ressource schon immer große Bedeutung zu. Erste Versuche, Wasser-Hebesysteme in der Landwirtschaft einzusetzen, lassen sich im Hellenis- tischen Alexandria nachweisen. Die Nutzbarkeit solcher Hebesysteme war eingeschränkt einerseits durch ihre individuelle Konstruktion, andererseits durch die Geologie vor Ort. Während dabei einige dieser Wasser-Hebesysteme täglichen Einsatz fanden, blieben andere ungenutzt oder gerieten auf Grund ihrer geringen Bedeutung oder ihrer Komplexität bis zu ihrer Wiederentdeckung in Vergessenheit. Wasser wurde damals auch als Energiequelle eingesetzt, wie zum Beispiel beim Schneiden von Steinen oder beim Mahlen von Korn. Sol- che Anwendungen stellen gleichsam den Anfang der antiken römischen Industrialisierung dar.