No Need to Shout: Bus Sweeps and the Psychology of Coercion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

„When Am I?“ – Zeitlichkeit in Der US-Serie LOST, Teil 2

GABRIELE SCHABACHER „When Am I?“ – Zeitlichkeit in der US-Serie LOST, Teil 2 Previously on … An der US-Serie LOST lässt sich eine systematische Nutzung der temporalen Di- mension beobachten: Auf den Ebenen von Erzählzeit und erzählter Zeit – das konnte der erste Teil dieses Beitrags zeigen – ist der Einsatz von story arcs überspan- nenden Flashbacks bzw. Flashforwards sowie eine handlungsseitig ausgeführte Thematisierung und Problematisierung von Zeitreisen und Teleportation für das Seriennarrativ zentral. Schon diese zeitlichen Relationen ermöglichen der Narra- tion entscheidende Inversionen und paradoxe Konstruktionen, die für die Serie LOST charakteristisch geworden sind. 1. Die dritte Zeit Eine dritte Dimension der Narration, um die es dem zweiten Teil dieses Beitrags geht, lässt sich nun keiner der beiden bisher thematisierten Gruppen eindeutig zuordnen, weder also der Erzählzeit und damit den stilistischen Mitteln im engeren Sinne, noch der erzählten Zeit, d. h. der inhaltlichen Ebene der Geschichte. Es handelt sich vielmehr um eine Gruppe von Phänomen, die sich durch eine spezifi - sche Übergängigkeit zwischen diesen beiden Kategorien auszeichnen. Daher wird im Folgenden auf die in der Serie geäußerten Vorahnungen, Time Loops, Bewusst- seinsreisen und Zeitsprünge einzugehen sein, um die Hybridisierung von Stilistik und Inhaltsmomenten der Narration zu verdeutlichen. Das Vorhandensein solcher hybrider Elemente ist es, das eine mögliche Erklärung für die besondere Faszinati- on an LOST und eine spezifi sch temporal motivierte Komplexität -

Memorial Book 2020

5781 CONGREGATION KOL AMI VIRTUAL CEMETERY It is a long standing Jewish tradition to visit the gravesites of loved ones in the period surrounding the High Holidays. While a personal visit to the cemetery is the preferred way to fulfill this mitzvah, circumstances may prevent such a trip. Thanks to the internet and a website called FindaGrave, those buried in Congregation Kol Ami plots, family members interred at other cemeteries anywhere in the world and those whose only memorial is in our minds and hearts, may be visited virtually. One feature of FindaGrave is the ability to create a virtual cemetery. A virtual cemetery gathers memorials of people who are interred in various physical cemeteries into one place. The Congregation Kol Ami Virtual Cemetery lists all interments in Kol Ami plots at Mount Hope and Mount Pleasant cemeteries. In addition, memorials for people who are buried around the globe, or whose ashes may have been scattered in the winds and waters of the planet, may be included in our virtual Kol Ami cemetery. The site may be visited by going to: http://tinyurl.com/KolAmiVirtualCemetery By clicking the name of an individual, you will be taken to his or her memorial page. There, you will find a photograph of the gravestone or other memorial (e.g. a plaque on a bench), as well as information taken from the stone, such as dates of birth and death. A few of the listings include biographical information entered by the creator of the memorial page. For questions about the virtual cemetery or to have a name added, please contact our temple office. -

Am2021-Program.Pdf

ASA is pleased to acknowledge the supporting partners of the 116th Virtual Annual Meeting 116th Virtual Annual Meeting Emancipatory Sociology: Rising to the Du Boisian Challenge 2021 Program Committee Aldon D. Morris, President, Northwestern University Rhacel Salazar Parreñas, Vice President, University of Southern California Nancy López, Secretary-Treasurer, University of New Mexico Joyce M. Bell, University of Chicago Hae Yeon Choo, University of Toronto Nicole Gonzalez Van Cleve, Brown University Jeff Goodwin, New York University Tod G. Hamilton, Princeton University Mignon R. Moore, Barnard College Pamela E. Oliver, University of Wisconsin-Madison Brittany C. Slatton, Texas Southern University Earl Wright, Rhodes College Land Acknowledgement and Recognition Before we can talk about sociology, power, inequality, we, the American Sociological Association (ASA), acknowledge that academic institutions, indeed the nation-state itself, was founded upon and continues to enact exclusions and erasures of Indigenous Peoples. This acknowledgement demonstrates a commitment to beginning the process of working to dismantle ongoing legacies of settler colonialism, and to recognize the hundreds of Indigenous Nations who continue to resist, live, and uphold their sacred relations across their lands. We also pay our respect to Indigenous elders past, present, and future and to those who have stewarded this land throughout the generations TABLE OF CONTENTS d Welcome from the ASA President..............................................................................................................................................................................1 -

The Missing Pieces of the Debate Over Federal Property Rights Legislation, 27 Hastings Const

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 27 Article 1 Number 1 Fall 1999 1-1-1999 The iM ssing Pieces of the Debate over Federal Property Rights Legislation Max Kidalov Richard H. Seamon Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Max Kidalov and Richard H. Seamon, The Missing Pieces of the Debate over Federal Property Rights Legislation, 27 Hastings Const. L.Q. 1 (1999). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol27/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES The Missing Pieces of the Debate Over Federal Property Rights Legislation by MAx KIDALov* AND RicHARD H. SEAMON** I. Introduction The 105t" Congress came very close to passing property-rights leg- islation that reflected a "new breed" of federal property-rights pro- posals.' Property-rights bills in earlier Congresses would have changed the substance of the Just Compensation Clause by making it easier to prove that government action had "taken" private property.2 In contrast, last year's proposed legislation ostensibly changed, not the substance of takings law, but the process for asserting takings claims in federal court. Opponents of these process-oriented takings bills as- serted, however, that the bills did change the substance of takings law, and for that reason were unconstitutional. The debate over the consti- tutionality of the bills has continuing importance in the 106th Con- gress, where new process-oriented takings bills have been introduced.3 The debate has broader importance as well, for it raises fundamental, unsettled questions about the power of the federal courts and Con- * Clerk to the Honorable Loren A. -

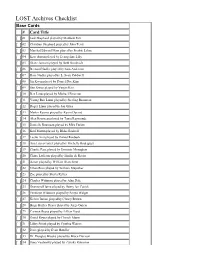

LOST Archives Checklist

LOST Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack Shephard played by Matthew Fox [ ] 02 Christian Shephard played by John Terry [ ] 03 Marshal Edward Mars played by Fredric Lehne [ ] 04 Kate Austin played by Evangeline Lilly [ ] 05 Diane Janssen played by Beth Broderick [ ] 06 Bernard Nadler played by Sam Anderson [ ] 07 Rose Nadler played by L. Scott Caldwell [ ] 08 Jin Kwon played by Daniel Dae Kim [ ] 09 Sun Kwon played by Yunjin Kim [ ] 10 Ben Linus played by Michael Emerson [ ] 11 Young Ben Linus played by Sterling Beaumon [ ] 12 Roger Linus played by Jon Gries [ ] 13 Martin Keamy played by Kevin Durand [ ] 14 Alex Rousseau played by Tania Raymonde [ ] 15 Danielle Rousseau played by Mira Furlan [ ] 16 Karl Martin played by Blake Bashoff [ ] 17 Leslie Arzt played by Daniel Roebuck [ ] 18 Ana Lucia Cortez played by Michelle Rodriguez [ ] 19 Charlie Pace played by Dominic Monaghan [ ] 20 Claire Littleton played by Emilie de Ravin [ ] 21 Aaron played by William Blanchette [ ] 22 Ethan Rom played by William Mapother [ ] 23 Zoe played by Sheila Kelley [ ] 24 Charles Widmore played by Alan Dale [ ] 25 Desmond Hume played by Henry Ian Cusick [ ] 26 Penelope Widmore played by Sonya Walger [ ] 27 Kelvin Inman played by Clancy Brown [ ] 28 Hugo Hurley Reyes played by Jorge Garcia [ ] 29 Carmen Reyes played by Lillian Hurst [ ] 30 David Reyes played by Cheech Marin [ ] 31 Libby Smith played by Cynthia Watros [ ] 32 Dave played by Evan Handler [ ] 33 Dr. Douglas Brooks played by Bruce Davison [ ] 34 Ilana Verdansky played by Zuleika -

A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies, Volume 7—Care Coordination”

Technical Review Number 9 Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies Volume 7—Care Coordination Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 290-02-0017 Prepared by: Stanford University–UCSF Evidence-based Practice Center, Stanford, CA Series Editors Kaveh G. Shojania, M.D., University of California, San Francisco Kathryn M. McDonald, M.M., Stanford University Robert M. Wachter, M.D., University of California, San Francisco Douglas K. Owens, M.D., M.S., VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, California; Stanford University Investigators Kathryn M. McDonald, M.M. Vandana Sundaram, M.P.H. Dena M. Bravata, M.D., M.S. Robyn Lewis, M.A. Nancy Lin, Sc.D. Sally A. Kraft, M.D., M.P.H. Moira McKinnon, B.A. Helen Paguntalan, M.S. Douglas K. Owens, M.D., M.S. AHRQ Publication No. 04(07)-0051-7 June 2007 This report is based on research conducted by the Stanford-UCSF Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract No. 290-02-0017). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the author(s), who are responsible for its contents, and do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. No statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The information in this report is intended to help clinicians, employers, policymakers, and others make informed decisions about the provision of health care services. -

Redalyc.Rose: Uma Ilha De Estereótipos Em Lost

Significação: revista de cultura audiovisual E-ISSN: 2316-7114 [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo Brasil de Almeida, Rogério; Pelegrini, Christian H. Rose: uma ilha de estereótipos em Lost Significação: revista de cultura audiovisual, vol. 40, núm. 39, enero-junio, 2013, pp. 243- 265 Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=609765999013 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto // Rose: uma ilha de estereótipos em Lost /////////////////// Rogério de Almeida1 Christian H. Pelegrini2 1. Doutor em educação pela Universidade de São Paulo. Professor da Faculdade de Educação da USP e pesquisador do Geifec (Grupo de Estudos sobre Itinerários de Formação em Educação e Cultura). E-mail: [email protected] 2. Doutorando na Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, professor dos cursos de comunicação social da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo e da Universidade São Judas Tadeu e pesquisador do Geifec. E-mail: [email protected] 2013 | ano 40 | nº39 | significação | 243 /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Resumo Este artigo é resultado de pesquisas realizadas pelo Geifec (Grupo de Estudos sobre Itinerários de Formação em Educação e Cultura) e tem por objetivo a análise das formas de representação da personagem Rose Nadler, da série americana Lost. Mulher, negra, próxima dos 60 anos, acima do peso, Rose está na intersecção de uma série de grupos minoritários, e sua presença na tela incorre na sobreposição de estereótipos pouco comuns na série. -

The Studio Potter Archives

ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM CERAMICS RESEARCH CENTER THE STUDIO POTTER ARCHIVES 2015 Contact Information Arizona State University Art Museum Ceramics Research Center P.O. Box 872911 Tempe, AZ 85287-2911 http://asuartmuseum.asu.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS Collection Overview 3 Administrative Information 3 Biographical Note 3 Scope and Content Note 4 Arrangement 5 Series 1: Magazine Issues: Volume 1, No. 1 – Volume 32, No. 2 Volume 1, No. 1 5 Volume 2, Nos. 1-2 6 Volume 3, Nos. 1-2 7 Volume 4, Nos. 1-2 9 Volume 5, Nos. 1-2 11 Volume 6, Nos. 1-2 13 Volume 7, Nos. 1-2 15 Volume 8, Nos. 1-2 17 Volume 9, Nos. 1-2 19 Volume 10, Nos. 1-2 21 Volume 11, Nos. 1-2 23 Volume 12, Nos. 1-2 26 Volume 13, Nos. 1-2 29 Volume 14, Nos. 1-2 32 Volume 15, Nos. 1-2 34 Volume 16, Nos. 1-2 38 Volume 17, Nos. 1-2 40 Volume 18, Nos. 1-2 43 Volume 19, Nos. 1-2 46 Volume 20, Nos. 1-2 49 Volume 21, Nos. 1-2 53 Volume 22, Nos. 1-2 56 Volume 23, Nos. 1-2 58 Volume 24, Nos. 1-2 61 Volume 25, Nos. 1-2 64 Volume 26, Nos. 1-2 67 1 Volume 27, Nos. 1-2 69 Volume 28, Nos. 1-2 72 Volume 29, Nos. 1-2 74 Volume 30, Nos. 1-2 77 Volume 31, Nos. 1-2 81 Volume 32, Nos. 1-2 83 Series 2: Other Publications Studio Potter Network News 84 Studio Potter Book 84 Series 3: Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Images Miscellaneous Manuscripts 85 Miscellaneous Images 86 Series 4: 20th Anniversary Collection 86 Series 5: Administration Daniel Clark Foundation/Studio Potter Foundation 87 Correspondence 88 Miscellaneous Files 88 Series 6: Oversized Items 88 Series 7: Audio Cassettes 89 Series 8: Magazine Issues: Volume 33, No. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 166 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2020 No. 24 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was PRESCRIPTION DRUG COSTS As a number of my Republican col- called to order by the President pro Mr. GRASSLEY. Last night, in the leagues have confessed, the House man- tempore (Mr. GRASSLEY). State of the Union Address, President agers have proven their case. President f Trump called on Congress to put bipar- Trump did sanction a corrupt con- spiracy to smear a political opponent, PRAYER tisan legislation to lower prescription drug prices on his desk and that he former Vice President Joe Biden. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- would sign it. President Trump assigned Rudy fered the following prayer: Here are the facts. The House is con- Giuliani, his personal lawyer, to ac- Let us pray. trolled by Democrats. The Senate re- complish that goal by arranging sham Strong Deliverer, our shelter in the quires bipartisanship to get any legis- investigations by the Government of time of storms, we acknowledge today lating done. There are only a couple of Ukraine. President Trump advanced that You are God and we are not. You months left before the campaign season his corrupt scheme by instructing the don’t disappoint those who trust in will likely impede anything from being three amigos—Ambassador Volker, You, for You are our fortress and bul- accomplished in this Congress. -

Uma Ilha De Estereótipos Em Lost

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cadernos Espinosanos (E-Journal) // Rose: uma ilha de estereótipos em Lost /////////////////// Rogério de Almeida1 Christian H. Pelegrini2 1. Doutor em educação pela Universidade de São Paulo. Professor da Faculdade de Educação da USP e pesquisador do Geifec (Grupo de Estudos sobre Itinerários de Formação em Educação e Cultura). E-mail: [email protected] 2. Doutorando na Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, professor dos cursos de comunicação social da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo e da Universidade São Judas Tadeu e pesquisador do Geifec. E-mail: [email protected] 2013 | ano 40 | nº39 | significação | 243 /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Resumo Este artigo é resultado de pesquisas realizadas pelo Geifec (Grupo de Estudos sobre Itinerários de Formação em Educação e Cultura) e tem por objetivo a análise das formas de representação da personagem Rose Nadler, da série americana Lost. Mulher, negra, próxima dos 60 anos, acima do peso, Rose está na intersecção de uma série de grupos minoritários, e sua presença na tela incorre na sobreposição de estereótipos pouco comuns na série. O referencial teórico toma por base as contribuições de Mazzara (1998) e Mittell (2010), e a metodologia parte do levantamento das aparições da personagem Rose ao longo das três primeiras temporadas da série, com captura de imagens e transcrição de diálogos. Palavras-chave Estereótipos, personagens secundários, séries televisivas. Abstract This paper is the result of research made on Geifec and has as a goal to analyze the modes of representation of the character Rose Nadler, from the American series Lost. -

Foreword: the Degradation of American Democracy—And the Court

VOLUME 134 NOVEMBER 2020 NUMBER 1 © 2020 by The Harvard Law Review Association THE SUPREME COURT 2019 TERM FOREWORD: THE DEGRADATION OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY — AND THE COURT† Michael J. Klarman CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 4 I. THE DEGRADATION OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY ............................................................ 11 A. The Authoritarian Playbook ............................................................................................. 11 B. President Trump’s Authoritarian Bent ............................................................................ 19 1. Attacks on Freedom of the Press and Freedom of Speech .......................................... 20 2. Attacks on an Independent Judiciary .......................................................................... 22 3. Politicizing Law Enforcement ...................................................................................... 23 4. Politicizing the Rest of the Government ...................................................................... 25 5. Using Government Office for Private Gain .................................................................. 28 6. Encouraging Violence .................................................................................................... 32 7. Racism ............................................................................................................................. 33 8. Lies .................................................................................................................................. -

Madoff Affidavit Exhibits SEND for Attorneys 02-03-09.Xlsx

EXHIBIT A Customers A-1 Customers LINE1 LINE2 LINE3 LINE4 LINE5 LINE6 1000 CONNECTICUT AVE ASSOC 1919 M STREET NW #320 WASHINGTON, DC 20036 151797 CANADA INC C/O JUDY PENCER 10 BELLAIR ST, SOUTH PENTHOUSE TORONTO ONTARIO CANADA M5R3T8 1620 K STREET ASSOCIATES LIMITED PARTNER C/O CHARLES E SMITH MANAGEMENT 2345 CRYSTAL DRIVE ARLINGTON, VA 22202 1700 K STREET ASSOCIATES LLC 1919 M STREET NW #320 WASHINGTON, DC 20036 1776 K STREET ASSOC LTD PTR C/O CHARLES E SMITH MGMT INC 2345 CRYSTAL DRIVE ARLINGTON, VA 22202 1919 M STREET ASSOCIATES LP 1919 M STREET NW #320 WASHINGTON, DC 20036 1973 MASTERS VACATION FUND C/O DAVID FRIEHLING FOUR HIGH TOR ROAD NEW CITY, NY 10956 1973 MASTERS VACATION FUND C/O JEROME HOROWITZ 17395 BRIDLEWAY TRAIL BOCA RATON, FL 33496 1987 JIH DECENDENT TRUST #2 NEWTON N MINOW TRUSTEE 200 WEST MADISON SUITE #3800 CHICAGO, IL 60606 1987 JIH DESCENDENTS TRUST #3 DAVID MOORE & DANIEL TISCH TTE ATTN: TERRY LAHENS 220 SUNRISE AVENUE SUITE 210 PALM BEACH, FL 33480 1994 BERNHARD FAMILY PTNRSHIP ATTN: LORA BURGESS C/O KERKERING BARBERIO CPA'S 1990 MAIN STREET SUITE 801 SARASOTA, FL 34236 1994 TRUST FOR THE CHILDREN OF STANLEY AND PAMELA CHAIS AL ANGEL & MARK CHAIS TRUSTEE 4 ROCKY WAY LLEWELLYN PARK WEST ORANGE, NJ 07052 1996 TRUST FOR THE BENEFIT OF THE ISSUE OF ROBIN L SAND C/O DAVID LANCE JR 219 SOUTH STREET NEW PROVIDENCE, NJ 07974 1998 CLUB STEIN FAMILY PARTNERSHIP C/O DONALD O STEIN 100 RING ROAD WEST GARDEN CITY, NY 11530 1999 NADLER FAMILY TRUST EDITH L NADLER AND SIDNEY KAPLAN TSTEES 408 WILSHIRE WALK HOPKINS, MN 55305