As a PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower-Class Violence in the Late Antique West

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by White Rose E-theses Online LOWER-CLASS VIOLENCE IN THE LATE ANTIQUE WEST MICHAEL HARVEY BURROWS SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS SCHOOL OF HISTORY JANUARY 2017 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Michael Harvey Burrows to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2016 The University of Leeds and Michael Harvey Burrows 2 Acknowledgements The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the support and assistance of many friends, family and colleagues. A few of these have made such a contribution that it would be disrespectful not to recognise them in particular. It has been a privilege to be a part of the cadre of students that came together under the supervision – directly or indirectly – of Ian Wood. I am grateful to Mark Tizzoni, Ricky Broome, Jason Berg, Tim Barnwell, Michael Kelly, Tommaso Leso, N. Kıvılcım Yavuz, Ioannis Papadopoulos, Hope Williard, Lia Sternizki and associate and fellow Yorkshireman Paul Gorton for their advice and debate. Ian, in particular, must be praised for his guidance, mastery of the comical anecdote and for bringing this group together. -

E.V. Shelestiuk a History of England (From Ancient Times to Restoration

E.V. Shelestiuk A History of England (from Ancient Times to Restoration) Е.В. Шелестюк История Англии с древних времен до эпохи реставрации монархии Chelyabinsk 2012 Аннотация Предлагаемое пособие представляет собой первую часть курса истории Англии - от древнейших времён до эпохи Карла II. Книга знакомит читателя с особенностями исторического развития страны, политическим строем и культурной жизнью Англии указанных эпох. Источниками послужили работы как зарубежных, так и отечественных специалистов. В основе структуры данного пособия лежат названия глав книг «История Англии. Тексты для чтения» (1-я часть) Г.С. Усовой и «История Англии для детей» Ч. Диккенса. Текст глав частично заимствован из указанных работ, а частично написан нами (41, 51, 63). Также во многие главы были включены наши дополнения, иллюстрации, отрывки из историографических источников, цитаты из оригинальных документов, из художественной, биографической и публицистической литературы. Пособие составлено в соответствии с требованиями программ МГУ по страноведению и истории стран изучаемого языка и рассчитано на студентов филологических, лингвистических факультетов, факультетов иностранных языков и перевода. Оно может быть также рекомендовано к изучению студентам-регионоведам, историкам и политологам. Курс «История Англии» может предварять курс страноведения англоязычных стран либо сопутствовать ему. Дисциплину рекомендуется вести два семестра, она рассчитана на 72 учебных часа. Отдельные материалы пособия могут использоваться при изучении специальных дисциплин (лингвокультурологии, -

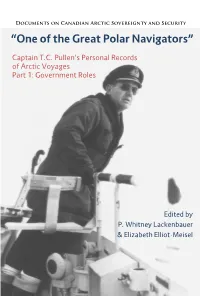

"One of the Great Polar Navigators": Captain T.C. Pullen's Personal

Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security “One of the Great Polar Navigators” Captain T.C. Pullen’s Personal Records of Arctic Voyages Part 1: Government Roles Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer & Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security (DCASS) ISSN 2368-4569 Series Editors: P. Whitney Lackenbauer Adam Lajeunesse Managing Editor: Ryan Dean “One of the Great Polar Navigators”: Captain T.C. Pullen’s Personal Records of Arctic Voyages, Volume 1: Official Roles P. Whitney Lackenbauer and Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel DCASS Number 12, 2018 Cover: Department of National Defence, Directorate of History and Heritage, BIOG P: Pullen, Thomas Charles, file 2004/55, folder 1. Cover design: Whitney Lackenbauer Centre for Military, Security and Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Strategic Studies St. Jerome’s University University of Calgary 290 Westmount Road N. 2500 University Dr. N.W. Waterloo, ON N2L 3G3 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 519.884.8110 ext. 28233 Tel: 403.220.4030 www.sju.ca/cfpf www.cmss.ucalgary.ca Arctic Institute of North America University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW, ES-1040 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 403-220-7515 http://arctic.ucalgary.ca/ Copyright © the authors/editors, 2018 Permission policies are outlined on our website http://cmss.ucalgary.ca/research/arctic-document-series “One of the Great Polar Navigators”: Captain T.C. Pullen’s Personal Records of Arctic Voyages Volume 1: Official Roles P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. and Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel, Ph.D. Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................. i Acronyms ............................................................................................................... xlv Part 1: H.M.C.S. -

And They Called Them “Galleanisti”

And They Called Them “Galleanisti”: The Rise of the Cronaca Sovversiva and the Formation of America’s Most Infamous Anarchist Faction (1895-1912) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Andrew Douglas Hoyt IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advised by Donna Gabaccia June 2018 Andrew Douglas Hoyt Copyright © 2018 i Acknowledgments This dissertation was made possible thanks to the support of numerous institutions including: the University of Minnesota, the Claremont Graduate University, the Italian American Studies Association, the UNICO Foundation, the Istituto Italiano di Cultura negli Stati Uniti, the Council of American Overseas Research Centers, and the American Academy in Rome. I would also like to thank the many invaluable archives that I visited for research, particularly: the Immigration History Resource Center, the Archivio Centrale dello Stato, the Archivio Giuseppe Pinelli, the Biblioteca Libertaria Armando Borghi, the Archivio Famiglia Berneri – Aurelio Chessa, the Centre International de Recherches sur l’Anarchisme, the International Institute of Social History, the Emma Goldman Paper’s Project, the Boston Public Library, the Aldrich Public Library, the Vermont Historical Society, the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, the Library of Congress, the Historic American Newspapers Project, and the National Digital Newspaper Program. Similarly, I owe a great debt of gratitude to tireless archivists whose work makes the writing of history -

Origins of the Scots

Origins of the Scots Introduction Scotland as we know it today evolved from the 9th to the 12th Centuries AD. Most casual readers of history are aware that the Picts and the Scots combined to form Alba c.850 AD, and Alba evolved into Scotland - but not everyone is aware how this happened and what the other components of what became Scotland were. In this short essay, I will outline the various peoples who combined to form the Scottish people and state. This paper is not designed to be scholarly in nature, but merely a brief survey of the situation to acquaint the reader with the basics. Sources of information are somewhat limited, since written records were unavailable in prehistoric times, which in Scotland means before the arrival of the Romans in the first century AD. The Romans came north after subduing southern Britain. One expects that the Roman view would be biased in their favor, so it is difficult to get an accurate picture from their records. After Rome adopted Christianity in the 4th century AD, church records became a source of information in Southern Britain, and by the 5th century AD, in Ireland, but this introduced a new bias in support of Christian peoples as opposed to those viewed by Christians at the time as heathens, pagans, or infidels. As Christian missionaries moved into northern Britain from several directions, more documents became available. So, let’s begin… Pre-Celts Around 12-13,000 BC, after the ice began to recede, humans returned to Britain, probably as hunter-gatherers. -

Country Studies Through Language: English-Speaking World (Лінгвокраїнозавство Країн Основної Іноземної Мови) Англ

НАЦІОНАЛЬНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ БІОРЕСУРСІВ І ПРИРОДОКОРИСТУВАННЯ УКРАЇНИ Кафедра романо-германських мов і перекладу Country Studies through Language: English-Speaking World (Лінгвокраїнозавство країн основної іноземної мови) англ. для студентів ОС «Бакалавр» галузі знань 03 «Гуманітарні науки» зі спеціальності 035 «Філологія» КИЇВ - 2016 УДК 811.111(075.8) ББК 81.432.1я73 Б12 Рекомендовано до друку вченою радою Національного університету біоресурсів і природокористування України (протокол № 5 від “23 ”листопада 2016р.) Рецензенти: Амеліна С. М. − доктор педагогічних наук, професор, завідувач кафедри іноземної філології і перекладу Національного університету біоресурсів і природокористування України Юденко О. І. − кандидат філологічних наук, доцент, завідувач кафедри іноземних мов Нацiональної академiї образотворчого мистецтва і архiтектури Галинська О.М. − кандидат філологічних наук, доцент кафедри ділової іноземної мови та міжнародної комунікації Національного університету харчових технологій Бабенко Олена Country Studies through Language: English-Speaking World /Лінгвокраїнозавство країн основної іноземної мови (англ.) Навчальний посібник для студентів ОС «Бакалавр» галузі знань 03 «Гуманітарні науки» зі спеціальності 035 «Філологія» : Вид-но НУБіП України, 2016. –324 с. Навчальний посібник з дисципліни «Лінгвокраїнозавство країн основної іноземної мови» спрямовано на вдосконалення практичної підготовки майбутніх фахівців з іноземної мови (учителів англійської мови, перекладачів-референтів) шляхом розширення їхнього словникового запасу в -

Lot 1 Petrie, George. the Ecclesiastical

Purcell Auctioneers - Auction of a Collection of Irish Historical Interest Books Including Maps, Journals, Periodicals, Pamphlets, Ephemera, GAA Interest Etc. on Behalf of the Executors of Two Deceased Estates. - Starts 21 Apr 2021 Lot 1 Petrie, George. The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland, Anterior to the Anglo-Norman Invasion; Comprising an Essay on the Origin and Uses of the Round Towers of Ireland. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 1845. Pp. 521. Illustrated. Contemporary brown cloth Estimate: 60 - 100 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 2 Dr. P. Voorhoeve. The Chester Beatty Library – A Catalogue of the Batar Manuscripts. Dublin 1961. Colour engravings and numerous text illustrations. Estimate: 40 - 50 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 3 Arthur J. Arberry. The Koran Illuminated – A Handlist of the Korans in the Chester Beatty Library. Dublin 1967. With 71 full page plates, eleven in fine colouring. Estimate: 80 - 100 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 4 O'Conner, Kieran. (Signed). The Archaeology of Medieval Rural Settlement in Ireland Royal Irish Academy 1998 Estimate: 30 - 60 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 5 Vere Foster. An Irish Benefactor by McNeill. 1971; Recollections by William O’Brien. 1905; Before the Lamps went out by Geoffrey Marcus – Irish Crisis etc. -

A Brief History of Ireland Free

FREE A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRELAND PDF Richard Killeen | 352 pages | 16 Jan 2012 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781849014397 | English | London, United Kingdom A Brief History of Ireland by Richard Killeen Covid Updates: How to contact us and useful information. Historians estimate that Ireland was first settled by humans at a relatively late stage in European terms — about 10, years ago. Around BC it is estimated that the first farmers arrived in Ireland. Farming marked the arrival of the new Stone Age. The Celts had a huge influence on Ireland. Many famous Irish myths stem from stories about Celtic warriors. The current first official language of the Republic of Ireland, Irish or Gaeilge stems from Celtic language. Following the arrival of Saint Patrick and other Christian missionaries in the early to mid-5th century, Christianity took A Brief History of Ireland the indigenous pagan religion A Brief History of Ireland the year AD. Irish Christian scholars excelled in the study of Latin, Greek and Christian theology in monasteries throughout Ireland. The arts of manuscript illumination, metalworking and sculpture flourished and produced such treasures as the Book of Kells, A Brief History of Ireland jewellery, and the many carved stone crosses that can still be seen across the country. At the end of the 8th century and during the 9th century Vikings, from where we now call Scandinavia, began to invade and then gradually settle into and mix with Irish society. The 12th century saw the arrival of the Normans. The Normans built walled towns, castles and churches. They also increased agriculture and commerce in Ireland. -

A Methodological Reassessment of Greek and Roman Battlefield Archaeology

Collecting the Field: A Methodological Reassessment of Greek and Roman Battlefield Archaeology. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Joanne Elizabeth Ball February 2016 Collecting the Field: A Methodological Reassessment of Greek and Roman Battlefield Archaeology. Joanne Elizabeth Ball. Abstract. The study of Greek and Roman battles has been an area of academic interest for centuries, but understanding of the archaeological potential of battlefields from classical antiquity has remained severely limited. The field has stagnated partly through over- deference to unsuitable ancient literary accounts, compounded by a lack of exploration of the site formation processes on such battlefields. This has resulted in an unjustified pessimism among some ancient historians and battlefield archaeologists that any significant information can be extracted from the exploration of such sites. Several ancient battlefields, and numerous smaller-scale conflict sites, have been identified and excavated in the previous three decades. In spite of these projects, there has been a general absence of integration of the evidence from these sites into a wider understanding of the archaeology of ancient battlefields, and consequently, a failure to use the evidence to identify and locate new sites. Drawing evidence from a number of excavated conflict sites from the classical world, particularly the Roman battlefields at Baecula, Kalkriese, and Harzhorn, this thesis presents an argument for a more archaeologically-dominated approach to exploring Greek and Roman battlefields, despite the pragmatic challenges in doing so. While the ancient literary sources have been the primary base for much of the last two centuries, they contain little reliable or accurate evidence with regards to geographic or topographic location of specific battlefields or the post-battle processing of battle-deposited material. -

Kerr, John Latimer (1991) the Role and Character of the Praetorian Guard and the Praetorian Prefecture Until the Accession of Vespasian

Kerr, John Latimer (1991) The role and character of the praetorian guard and the praetorian prefecture until the accession of Vespasian. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/875/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE ROLE AND CHARACTER OF THE PRAETORIAN GUARD AND THE PRAETORIAN PREFECTURE UNTIL THE ACCESSION OF VESPASIAN JOHN LATIMER KERR PH. D. THESIS DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS 1991 Lý k\) e" vc %0 t-0 Cn JOHN LATIMER KERR 1991 C0NTENTS. Page Acknowledgements. List of Illustrations. Summary. I The Augustan Guard and its Predecessors. 1 II The Praetorian Guard of Tiberius - AD. 14 to AD. 31. 15 III The Praetorian Guard from the Death of Seianus to the Assassination of Gaius. 41 IV The Praetorian Guard of Claudius. 60 V The Praetorian Guard of Nero. 84 VI The Praetorian Guard from the Death of Nero to the Accession of Vespasian. 116 VII The Praetorian Guard as a Political Force. 141 VIII The Praetorian Guard as a Military Force. -

PLAYBOOK COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety

The Fall of Roman Britain PLAYBOOK COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Multiplayer Example of Play . 2 Designer Notes. 64 Non-Players Orientation. 16 Non-Player Design Notes . 65 Victory Descriptions . 27 Sources . 66 The Pendragon Chronicles . 28 Gazetteer . 68 Event Notes . 42 Pronunciation Guide . 70 © 2017 GMT Games LLC • P .O . Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232 • www .GMTGames .com 2 Pendragon ~ Playbook Multiplayer Example of Play or Renown (for Barbarians) that each Faction has (1.8). Go ahead and “They, moved, as far as was possible for human nature, put a cylinder in each Faction’s color on the Edge Track at the numbers by the tale of such a tragedy, make speed, like the flight indicated: Dux is red, Scotti green, Saxon black, Civitates blue (1 .5) . of eagles, unexpected in quick movements of cavalry on The remaining four cylinders are for Eligibility (2 .2) . They always land and of mariners by sea; before long they plunge their start the game in the Eligible box on the Sequence of Play track—put terrible swords in the necks of the enemies; the massacre them there . they inflict is to be compared to the fall of leaves at the Put the blue pawn along the Edge Track between 36 and 37 and fixed time, just like a mountain torrent, swollen by numer- the red pawn between 75 and 76 . The pawns mark current victory ous streams after storms, sweeps over its bed in its noisy conditions for the Civitates and Dux Factions, respectively, which course; […]” may change over time as the Roman Imperium deteriorates (6.8, Gildas (De Excidio Britanniae, Part I.17) 7 .2) . -

Gods of War : Historys Greatest Military Rivals Ebook

GODS OF WAR : HISTORYS GREATEST MILITARY RIVALS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Lacey | 416 pages | 19 May 2020 | Bantam | 9780345547552 | English | United States Gods of War : Historys Greatest Military Rivals PDF Book Some three decades later, his grandson Shah Jahan built that most potent emblem of the Mughals, the Taj Mahal. This event is sometimes referred to as the 'Great Conspiracy'. Moment of Battle. Matthew Lockwood is assistant professor of history at the University of Alabama. Caesar refused and, in a bold and decisive maneuver, directed his army to cross the Rubicon River into Italy, triggering a civil war between his supporters and those of Pompey. You are leaving AARP. Aulus Plautius, commander of the invasion force, was appointed first Roman governor of Britain, but the majority of the island would not be pacified for at least another 50 years. After the usurper Constantine III crossed to the continent with part of the army to fight for supreme power, Britons may have successfully fought off a Saxon incursion on their own in AD. Read Review: In Zanesville. But if you see something that doesn't look right, click here to contact us! Since its start a century ago, Communism, a political and economic ideology that calls for a classless, government-controlled society in which everything is shared equally, has seen a series of surges—and declines. History at Home. No Room for Error. May 19, Minutes Buy. Around this time the records also show the first use of the word 'Picts' to describe an amalgamation of tribes in northern Scotland. During a year reign, this almost exact contemporary of the English queen Elizabeth I transformed a foreign occupation into a strong, cohesive empire of million ethnically and religiously diverse people.