George E. Yoos Simplifying Complexity. Rhetoric and the Social Politics of Dealing with Ignorance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve Reich's Phases of Phases: a Comparison of Electric

Steve Reich’s Phases of Phases: A Comparison of Electric Counterpoint and Radio Rewrite Erin Main, May 12th, 2016 21M.260, WC: 3478 Introduction. Minimalism developed primarily during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s amidst a rising counterculture in America. Minimalist artists in the 50s defied expectations of what “art” should be; one example is the color fields of artists such as Ad Reinhardt.1 Minimalist artists focused on the very deliberate creation of works that were comprised of the smallest amount of discernible qualities; with the aforementioned color fields, the viewer was intended to observe the minutiae of the brush strokes of the artist.2 In the mid-60s, minimalist music also started to take hold, driven by the efforts of composers Terry Riley, La Monte Young, Philip Glass, and Steve Reich.3 Reich is well-known for pioneering process-based music, as established in his 1968 essay “Music as a Gradual Process.”4 Process-based music is characterized by its minimal amount of material, with development (a musical process) occurring through changes in the material over a period of time.5 Reich’s most prominent type of process is phase shifting, which involves “placing a simple repeating pattern in different combinations with itself.”6 Due to the very nature of process-based composition, Reich’s music has a “structurally lucid aesthetic,” as the material 1 Jonathan W. Bernard, “The Minimalist Aesthetic in the Plastic Arts and in Music,” Perspectives of New Music 31.1 (1993): 94. Web. 2 Ibid, 95. 3 Ibid, 86. 4 Steve Reich and Paul Hillier, ed., “Music as a Gradual Process,” Writings about Music, 1965–2000, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 9–11. -

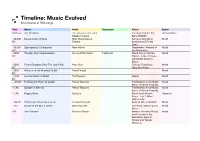

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Steve Reich Selected Reviews

Steve Reich Selected Reviews Runner – Royal Ballet Royal Opera House (November 2016) “McGregor pairs Reich’s 1965 looped tape composition It’s Gonna Rain with Runner, a piece written 50 years later. The first piece is fractured and apocalyptic (a preacher is predicting the end of the world after all), while the second – the new Reich – is hopeful, harmonic, healing… McGregor’s choreography segues from frantic exposition, almost automated in its pained realisation of impending disaster, to a more sumptuous expression of humanity and haven.” – Debra Craine, The Times **** “… Runner is a calmly luminous orchestral piece with the pulsating, propulsive rhythms that animate much of Mr Reich’s music. Here, coloured lights play across the grid, and a line of dancers spools in silhouette along one wall, as duets, trios and larger groupings mutate centre stage.” – Roslyn Sulcas, The New York Times Pulse – International Contemporary Ensemble Carnegie Hall (November 2016) “Beauty is a consistent quality of Reich’s recent music, and the most beautiful of all has to be Pulse , which was simple and luminous… At the bottom of Pulse was a constant eight-note throb from an electric bass through shifting meters. On top, there was a marvellous long-limbed, lyrical melody, repeated at times in tutti, at others in a closely mirrored canon.” – George Grella , New York Classical Review “Pulse , for small ensemble, begins with the strings making swooping lyrical lines, as at the start of Appalachian Spring : The mood is one of emerging, rising. A gentle, yes, pulse – quick but not pounding – emerges behind it, soon joined by a meatier, lower throb in the electric bass.” – Zachary Woolfe , The New York Times “If there has long been a sense that Reich’s early work is his best, the European premiere of Pulse (2016), given by Britten Sinfonia as the centrepiece of the first day of Steve Reich at 80, gives pause for thought. -

LIVING NETWORKS Leading Your Company, Customers, and Partners in the Hyper-Connected Economy

LIVING NETWORKS Leading Your Company, Customers, and Partners in the Hyper-Connected Economy Table of Contents Part 1: Evol ving Networks Chapter 1 - The Networks Come Alive: What the Changing Flow of Information and Ideas Means For Business 3 Chapter 2 - Emerging Technologies: How Standards and Integration Are Driving Business Strategy 19 Part 2: Evolving Organizations Chapter 3 - The New Organization: Leadership Across Blurring Boundaries 39 Chapter 4 - Relationship Rules: Building Trust and Attention in the Tangled Web 59 Chapter 5 - Distributed Innovation: Intellectual Property in a Collaborative World 79 Chapter 6 - Network Presence: Harnessing the Flow of Marketing, Customer Feedback, and Knowledge 101 Part 3: Evolving Strategy Chapter 7 - The Flow Economy: Opportunities and Risks in the New Convergence 123 Chapter 8 - Next Generation Content Distribution: Creating Value When Digital Products Flow Freely 149 Chapter 9 - The Flow of Services: Reframing Digital and Professional Services 167 Chapter 10 - Liberating Individuals: Network Strategy for Free Agents 191 Part 4: Future Networks Chapter 11 - Future Networks: The Evolution of Business 207 What Business Leaders Say About Living Networks "I'm not sure that even Ross Dawson realizes how radical—and how likely—his vision of the future is. Ideas that spread win, and organizations that spawn them will be in charge." - Seth Godin, author, Unleashing the Ideavirus , the #1 selling e-book in history "Dawson is exactly right—pervasive networking profoundly changes the business models and strategies required for success. Living Networks provides invaluable insights for decision makers wanting to prosper in an increasingly complex and demanding business environment." - Don Tapscott , author, Wikinomics "Ross Dawson argues persuasively that leading economies are driven by the flow of information and ideas. -

L}-~ UW Modern Music Ensemble UW MUSIC

C(JW\~t\{t elISe N\ ~ 3 f\lIf\ r:g' SCHOOL OF MUSIC V!J\':!J UNIVERSITY of WASHINGTON Jo 1(0 l}-~ UW Modern Music Ensemble Cristi na L. Valdes, Director presents Steve Reich An 80th Birthday Celebration with special guests UW Percussion Ensemble Bonnie Whiting, Director Tuesday, December 6,2016 7:30 PM, Meany Theater UW MUSIC 2016-17 SEASON PROGRAM re-rnMf!..s, ValdL-s 2- PENDULUM MUSIC (1968, revised 1973) to, 'i/ Vijay Chalasani, Natalie Ham, Hexin Qiao, AlexanderTu Doug Niemela, technical director 3 DRUMMING, Part I(1971) I <r5 ~ 2. f University of Washington Percussion Ensemble David Gaskey, Aidan Gold, David Norgaard, Emerson Wahl Bonnie Whiting, director f TRIPLE QUARTET (1998) I'-f ~:3 '1 Erin Kelly &Halie Borror, violins / Vijay Chalasani, viola / Isabella Kodama, cello Matt Stearns, sound engineer INTERMISSION / CLAPPING MUSIC(1972) 5".2-7 Vijay Chalasani, Isabella Kodama, Hexin Qiao, AlexanderTu VERMONT COUNTERPOINT (1982) 9 ; L'S Gemma Goday Ofaz-Corralejo, flute Matt Stearns, sound engineer -3 RADIO REWRITE (2012) 19: 53 Erin Kelly &Halie Borror, violins Vijay Chalasani, viola Chris Young, cello . Natalie Ham, flute Alexander Tu, clarinet Emerson Wahl &Aidan Gold, vibraphones Hexin Qiao &Yimo Zhang, piano Tony Lefaive, electric bass Mario Alejandro Torres, conductor The University of Washington Modern Music Ensemble is excited to present an all-Steve Reich concert in celebration of the iconic 20th century composer's 80th birthday. Along with Philip Glass and Terry Riley, Reich's unique musical style and compositional voice helped shape the minimalistic movement. His techniques of phasing, tape loops, and rhythmic pulsing integrated into astatic harmony creating aworld of visceral thought that invites the mind to follow the process of unfolding music. -

Reading Passages

Assessment 2 Session 1: Reading Passages Questions #1–46 Read the passage. Then answer the questions that follow. from Langston Hughes: Poet of the People by Sylvia Kamerman, adapted excerpts from “Langston Hughes: Poet of the People” from The Big Book of Large-Cast Plays SCENE 1 TIME: Summer, 1920. 1 SETTING: Study in James Hughes’s home near Mexico City. A desk, chair, and wastebasket are center. Accountant’s ledger lies closed on edge of desk. Floor vase with tall pampas grass stands nearby. 2 AT RISE: LANGSTON HUGHES sits writing at desk. SEÑORA GARCIA enters, holding feather duster. 3 SEÑORA GARCIA: Señor Langston, how can you sit in one place for hours just writing? 4 LANGSTON (Leaning back): Señora Garcia, if I could spend my whole life writing, I’d be happy. 5 SEÑORA GARCIA (Dusting vase): You are a true artist, Señor Langston. (Turns; sighs) It is too bad that your father does not understand. You two belong to different worlds. You are a dreamer, and he is such a practical man. (Door slams off) . Go On Assessment 2 69 ©Curriculum Associates, LLC Copying is not permitted. 6 (MR. HUGHES enters, frowning.) 7 SEÑORA GARCIA (Turns with big smile): Buenas días, Señor Hughes. We were not expecting you back from Toluca so soon. 8 MR. HUGHES: Hello, Señora Garcia. (As he removes his poncho) Langston? 9 LANGSTON (Rising; uncomfortably): Hello, Father. (MR. HUGHES gives poncho to SEÑORA GARCIA, who exits with it.) 10 MR. HUGHES: Well, Langston, let me see what progress you’ve made with the accounting problems. -

(“Agreement”) Covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS

INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS TELEVISION PROGRAMS and OTHER PRODUCTION between The WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA (the “Guild”) and The CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION (“CMPA”) and ASSOCIATION QUÉBÉCOISE DE LA PRODUCTION MÉDIATIQUE (“AQPM”) (the “Associations”) March 16, 2015 to December 31, 2017 © 2015 WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA and CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION and the ASSOCIATION QUÉBÉCOISE DE LA PRODUCTION MÉDIATIQUE. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A: General – All Productions p. 1 Article A1 Recognition, Application and Term p. 1 Article A2 Definitions p. 4 Article A3 General Provisions p. 14 Article A4 No Strike and Unfair Declaration p. 15 Article A5 Grievance Procedures and Resolution p. 16 Article A6 Speculative Writing, Sample Pages and Unsolicited Scripts p. 22 Article A7 Copyright and Contracts; Warranties, Indemnities and Rights p. 23 Article A8 Story Editors and Story Consultants p. 29 Article A9 Credits p. 30 Article A10 Security for Payment p. 41 Article A11 Payments p. 43 Article A12 Administration Fee p. 50 Article A13 Insurance and Retirement Plan, Deductions from Writer’s Fees p. 51 Article A14 Contributions and Deductions from Writer’s Fees in the case of Waivers p. 53 Section B: Conditions Governing Engagement p. 54 Article B1 Conditions Governing Engagement for all Program Types p. 54 Article B2 Optional Bibles, Script/Program Development p. 60 Article B3 Options p. 61 Section C: Additional Conditions and Minimum Compensation by Program Type p. 63 Article C1 Feature Film p. 63 Article C2 Optional Incentive Plan for Feature Films p. 66 Article C3 Television Production (Television Movies) p. -

The Pleasure of the Intertext: Towards a Cognitive Poetics of Adaptation

!1 THE PLEASURE OF THE INTERTEXT: TOWARDS A COGNITIVE POETICS OF ADAPTATION A dissertation presented by Meg Tarquinio to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April, 2017 !2 THE PLEASURE OF THE INTERTEXT: TOWARDS A COGNITIVE POETICS OF ADAPTATION by Meg Tarquinio ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April, 2017 !3 ABSTRACT The field of adaptation studies has been diagnosed as lacking consensus around its main tenets, especially those that would build a strong ontological foundation. This study participates in the burgeoning critical approach that places cognitive science in conversation with literary theory, looking towards the start of a cognitive turn in adaptation studies. Specifically, I offer the axiom that adaptations are analogies. In other words, I advance the original argument that adaptations are the textual expression of the cognitive function of analogy. Here, I’m using a cognitive theory of analogy as the partial mapping of knowledge (objects and relations) from a source domain to a target domain. From this vantage point, I reassess the theoretical tensions and analytical practices of adaptation studies. For instance, the idea of essence is an anathema within academic studies of adaptation, yet it continues to hold sway within popular discourse. My approach allows for a productive return to essence, not as some mystical quality inherent in an original text and then indescribably transmitted to its adaptation, but as the expression of a key sub-process of analogical reasoning – what Douglas Hofstadter refers to, conveniently, as “essence” or “gist extraction.” This line of argument demonstrates the degree to which André Bazin’s 1948 theorization of adaptation is in line with this cognitive version of essence. -

"Electric Counterpoint" for Marimba and Vibraphone

Adapting Reich’s “Electric Counterpoint” for Marimba and Vibraphone By James W. Doyle he minimalist work “Electric Counterpoint” was commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival and composed for gui- tarist Pat Metheny in 1987 by Steve Reich.1 The piece followed “Vermont Counterpoint” (1982) for flute and “New York Counterpoint” (1985) Tfor clarinet, completing a series of works for soloist performing with self-made prerecorded tracks.2 Metheny’s recording of the work was featured on the album Different Trains. Reich composed the work for either 12 pre-recorded parts and live performer, or soloist and guitar ensemble. Percussionist Svet Stoyanov arranged and recorded “Electric Counterpoint” in 2008 for marimba and vibraphone, and percussionist Kuniko Kato arranged and recorded the composition in 2009–10 utilizing steel pans, marimba, and vibra- phone. Jonny Greenwood, guitarist with the band Radiohead, also recorded the work, ultimately leading to Reich’s discovery of Radiohead’s music and his subse- quent composition, “Radio Rewrite.”3 The three-movement work, Fast-Slow-Fast, each performed without pause, is a frequently-used form by Reich. RECORDING Following a similar recording adaptation as Stoyanov, I prepared and prere- corded the parts in January 2015 for live performance. The first movement, pre- recorded and performed exclusively on marimba, begins with a gently-swelling introduction that transitions into developing constructs based on Reich’s study of Central African horn music.4 The second movement is a slow counterpoint primarily prerecorded and performed on vibraphone with swelling harmonies on prerecorded bass marimba. The final movement combines marimba and -vi braphone and alternates between E minor and C minor, as well as 3/2 and 12/8 approach for the microphones with a brighter microphone for the low end and a meters. -

Radio Rewrite Steve Reich Radio Rewrite Electric Counterpoint Jonny Greenwood, Guitar (1987) 14:41 Commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music’S Next Wave Festival

radio rewrite steve reich radio rewrite electric counterpoint jonny greenwood, guitar (1987) 14:41 Commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival. 1. I. fast 6:51 World Premiere: November 5, 1987, by Pat Metheny, at the Brooklyn Academy 2. II. slow 3:21 of Music, Brooklyn, NY. Published by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company. 3. III. fast 4:29 4. piano counterpoint vicky chow, piano (1973, arr. 2011) 13:44 World Premiere: October 23, 2012, by Vincent Corver, at the Pearl, Doha, Qatar. arrangement of Six Pianos for piano and Published by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company. tape by Vincent Corver radio rewrite alarm will sound (2012) 17:28 alan pierson, conductor 5. I. fast 3:52 erin lesser, flute 6. II. slow 3:23 elisabeth stimpert, clarinet chris thompson, vibraphone 7. III. fast 3:21 matt smallcomb, vibraphone 8. IV. slow 3:53 john orfe, piano 9. V. fast 2:59 michael harley, piano courtney orlando, violin caleb burhans, violin nathan schram, viola stefan freund, violoncello miles brown, electric bass gavin chuck, managing director jason varvaro, production manager peter ferry, production assistant Commissioned by the London Sinfonietta with support from London Sinfonietta Entrepre- neurs and Pioneers including Sir Richard Arnold, Trevor Cook, Susan Grollet in memory of Mark Grollet and Richard Thomas; Alarm Will Sound and Stanford Live in honor of the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation with generous support from Van and Eddi Van Auken. World Premiere: March 5, 2013, by Sound Intermedia/London Sinfonietta/Brad Lubman, at the Royal Festival Hall, London. -

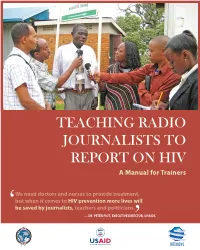

Radio Manual FINAL ABC Layout 1.Qxd

TEACHING RADIO JOURNALISTS TO REPORT ON HIV A Manual for Trainers We need doctors and nurses to provide treatment, ‘but when it comes to HIV prevention more lives will be saved by journalists, teachers and politicians. ̶ DR. PETER PIOT, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR,’ UNAIDS TEACHING RADIO JOURNALISTS TO REPORT ON HIV A Manual for Trainers Edited by Mia Malan Published by Internews Network’s Local Voices program in September 2008, Washington, D.C. www.internews.org +1 202-833-5740 Introduction Dear Trainer, This manual consists of lesson plans, exercises, and a training agenda developed by Internews Networks’ Local Voices programs to train radio journalists in HIV reporting. We hope this train- ing manual will help you to develop your own training program. At least 70% of these training exercises focus on teaching such radio reporting skills as inter- viewing, scriptwriting, digital sound editing, and sound recording. The rest focuses on HIV-spe- cific skills, such as language use and developing HIV knowledge. The Local Voices program is convinced that journalists will only be able to use HIV knowledge on radio effectively if they’re given the opportunity to also develop their storytelling and reporting skills. The CD that accompanies this manual contains all the training exercises and lesson plans in the manual. This enables you to adapt them to your region and training needs. The CD also con- tains sound used in some of the exercises. Chapter 5 contains a training agenda that works well for seven-day training workshops. You can either use it as a set agenda, or adjust it to better suit your needs. -

Community Radio in India

CR: A user’s guide to the technology A guide to the technology and technical parameters of community radio in India N. Ramakrishnan CR: A user's guide to the technology (2007) © UNESCO (2007) ISBN 81-89218-12-3 This publication may be produced in any media appropriately acknowledging UNESCO Published by : The United Nations Educational Scientific & Cultural Organization (UNESCO) UNESCO House B-5/29, Safdarjung Enclave New Delhi - 110019, India Phone: +91-11-26713000 Fax: +91-11-26713001/2 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unesco.org/newdelhi Author, Researcher: N.Ramakrishnan (Ideosync Media Combine) Editorial Team: Seema Nair, Sajan Venniyoor, Gitanjali Sah Cover & Binder Design: Inverted Commas, New Delhi Inside page design and graphics: Mensa Computers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi Photo credits : N.Ramakrishnan:Pages 4, 5, 6, 7, 13, 48, 57, 61, 73, 92-94, 96, 101,103, 104, 165-171, 204 Choy Arnaldo: Pages 14, 25, 26 UNESCO: Pages 11, 38, 76, 90, 100 All others images are courtesy the respective manufacturing companies Photographs of CR groups in action appear with permission of Samudayik Radio Mandakini Ki Awaaz and Hevalvaani Samudayik Radio, Uttarakhand Please send in comments and your experiences with this manual to [email protected] and: N. Ramakrishnan Ideosync Media Combine 177, Ashoka Enclave III Sector 35, Faridabad - 121 003 Haryana - INDIA Tel: +91-0129-4131883/6510156 Email: [email protected] Disclaimer: The author is responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this news piece and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organisation.