Steve Reich's Phases of Phases: a Comparison of Electric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

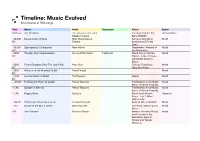

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

George E. Yoos Simplifying Complexity. Rhetoric and the Social Politics of Dealing with Ignorance

George E. Yoos Simplifying Complexity. Rhetoric and the Social Politics of Dealing with Ignorance George E. Yoos Simplifying Complexity Rhetoric and the Social Politics of Dealing with Ignorance Managing Editor: Magdalena Randall-Schab Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Copyright © 2015 George E. Yoos ISBN: 978-3-11-045056-9 e-ISBN: 978-3-11-045057-6 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Managing Editor: Magdalena Randall-Schab www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Ali Heshmati To my wife Mary Johanna Yoos ‘In the perception of the false, there is truth. In the understanding of ignorance, there is intelligence.’ A verbal statement made by J. Krishnamurti, an Indian Philosopher Contents A Preface on Aims VIII 1 Rhetorical limitations in the use of frames and perspectives 1 2 Aging and complexity 6 3 The human animal and its ascendance from ignorance 12 4 The work of Herbert Simon on Artificial Intelligence 25 5 Circular thinking and linear exposition -

Review of Rethinking Reich, Edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll Ap Siôn (Oxford University Press, 2019) *

Review of Rethinking Reich, Edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll ap Siôn (Oxford University Press, 2019) * Orit Hilewicz NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hilewicz.php KEYWORDS: Steve Reich, analysis, politics DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.1.0 Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory [1] This past September, a scandal erupted on social media when a 2018 book excerpt was posted that showed a few lines from an interview with British photographer and music writer Val Wilmer. Wilmer recounted her meeting with Steve Reich in the early 1970s: I was talking about a person who was playing with him—who happened to be an African-American who was a friend of mine. I can tell you this now because I feel I must . we were talking and I mentioned this man, and [Reich] said, “Oh yes, well of course, he’s one of the only Blacks you can talk to.” So I said, “Oh really?” He said, “Blacks are geing ridiculous in the States now.” And I thought, “This is a man who’s just done this piece called Drumming which everybody cites as a great thing. He’s gone and ripped off stuff he’s heard in Ghana—and he’s telling me that Blacks are ridiculous in the States now.” I rest my case. Wouldn’t you be politicized? (Wilmer 2018, 60) Following recent revelations of racist and misogynist statements by central musical figures and calls for music scholarship to come to terms with its underlying patriarchal and white racial frame, (1) the new edited volume on Reich suggests directions music scholarship could take in order to examine the political, economic, and cultural environments in which musical works are composed, performed, and received. -

Steve Reich Selected Reviews

Steve Reich Selected Reviews Runner – Royal Ballet Royal Opera House (November 2016) “McGregor pairs Reich’s 1965 looped tape composition It’s Gonna Rain with Runner, a piece written 50 years later. The first piece is fractured and apocalyptic (a preacher is predicting the end of the world after all), while the second – the new Reich – is hopeful, harmonic, healing… McGregor’s choreography segues from frantic exposition, almost automated in its pained realisation of impending disaster, to a more sumptuous expression of humanity and haven.” – Debra Craine, The Times **** “… Runner is a calmly luminous orchestral piece with the pulsating, propulsive rhythms that animate much of Mr Reich’s music. Here, coloured lights play across the grid, and a line of dancers spools in silhouette along one wall, as duets, trios and larger groupings mutate centre stage.” – Roslyn Sulcas, The New York Times Pulse – International Contemporary Ensemble Carnegie Hall (November 2016) “Beauty is a consistent quality of Reich’s recent music, and the most beautiful of all has to be Pulse , which was simple and luminous… At the bottom of Pulse was a constant eight-note throb from an electric bass through shifting meters. On top, there was a marvellous long-limbed, lyrical melody, repeated at times in tutti, at others in a closely mirrored canon.” – George Grella , New York Classical Review “Pulse , for small ensemble, begins with the strings making swooping lyrical lines, as at the start of Appalachian Spring : The mood is one of emerging, rising. A gentle, yes, pulse – quick but not pounding – emerges behind it, soon joined by a meatier, lower throb in the electric bass.” – Zachary Woolfe , The New York Times “If there has long been a sense that Reich’s early work is his best, the European premiere of Pulse (2016), given by Britten Sinfonia as the centrepiece of the first day of Steve Reich at 80, gives pause for thought. -

LIVING NETWORKS Leading Your Company, Customers, and Partners in the Hyper-Connected Economy

LIVING NETWORKS Leading Your Company, Customers, and Partners in the Hyper-Connected Economy Table of Contents Part 1: Evol ving Networks Chapter 1 - The Networks Come Alive: What the Changing Flow of Information and Ideas Means For Business 3 Chapter 2 - Emerging Technologies: How Standards and Integration Are Driving Business Strategy 19 Part 2: Evolving Organizations Chapter 3 - The New Organization: Leadership Across Blurring Boundaries 39 Chapter 4 - Relationship Rules: Building Trust and Attention in the Tangled Web 59 Chapter 5 - Distributed Innovation: Intellectual Property in a Collaborative World 79 Chapter 6 - Network Presence: Harnessing the Flow of Marketing, Customer Feedback, and Knowledge 101 Part 3: Evolving Strategy Chapter 7 - The Flow Economy: Opportunities and Risks in the New Convergence 123 Chapter 8 - Next Generation Content Distribution: Creating Value When Digital Products Flow Freely 149 Chapter 9 - The Flow of Services: Reframing Digital and Professional Services 167 Chapter 10 - Liberating Individuals: Network Strategy for Free Agents 191 Part 4: Future Networks Chapter 11 - Future Networks: The Evolution of Business 207 What Business Leaders Say About Living Networks "I'm not sure that even Ross Dawson realizes how radical—and how likely—his vision of the future is. Ideas that spread win, and organizations that spawn them will be in charge." - Seth Godin, author, Unleashing the Ideavirus , the #1 selling e-book in history "Dawson is exactly right—pervasive networking profoundly changes the business models and strategies required for success. Living Networks provides invaluable insights for decision makers wanting to prosper in an increasingly complex and demanding business environment." - Don Tapscott , author, Wikinomics "Ross Dawson argues persuasively that leading economies are driven by the flow of information and ideas. -

L}-~ UW Modern Music Ensemble UW MUSIC

C(JW\~t\{t elISe N\ ~ 3 f\lIf\ r:g' SCHOOL OF MUSIC V!J\':!J UNIVERSITY of WASHINGTON Jo 1(0 l}-~ UW Modern Music Ensemble Cristi na L. Valdes, Director presents Steve Reich An 80th Birthday Celebration with special guests UW Percussion Ensemble Bonnie Whiting, Director Tuesday, December 6,2016 7:30 PM, Meany Theater UW MUSIC 2016-17 SEASON PROGRAM re-rnMf!..s, ValdL-s 2- PENDULUM MUSIC (1968, revised 1973) to, 'i/ Vijay Chalasani, Natalie Ham, Hexin Qiao, AlexanderTu Doug Niemela, technical director 3 DRUMMING, Part I(1971) I <r5 ~ 2. f University of Washington Percussion Ensemble David Gaskey, Aidan Gold, David Norgaard, Emerson Wahl Bonnie Whiting, director f TRIPLE QUARTET (1998) I'-f ~:3 '1 Erin Kelly &Halie Borror, violins / Vijay Chalasani, viola / Isabella Kodama, cello Matt Stearns, sound engineer INTERMISSION / CLAPPING MUSIC(1972) 5".2-7 Vijay Chalasani, Isabella Kodama, Hexin Qiao, AlexanderTu VERMONT COUNTERPOINT (1982) 9 ; L'S Gemma Goday Ofaz-Corralejo, flute Matt Stearns, sound engineer -3 RADIO REWRITE (2012) 19: 53 Erin Kelly &Halie Borror, violins Vijay Chalasani, viola Chris Young, cello . Natalie Ham, flute Alexander Tu, clarinet Emerson Wahl &Aidan Gold, vibraphones Hexin Qiao &Yimo Zhang, piano Tony Lefaive, electric bass Mario Alejandro Torres, conductor The University of Washington Modern Music Ensemble is excited to present an all-Steve Reich concert in celebration of the iconic 20th century composer's 80th birthday. Along with Philip Glass and Terry Riley, Reich's unique musical style and compositional voice helped shape the minimalistic movement. His techniques of phasing, tape loops, and rhythmic pulsing integrated into astatic harmony creating aworld of visceral thought that invites the mind to follow the process of unfolding music. -

Reading Passages

Assessment 2 Session 1: Reading Passages Questions #1–46 Read the passage. Then answer the questions that follow. from Langston Hughes: Poet of the People by Sylvia Kamerman, adapted excerpts from “Langston Hughes: Poet of the People” from The Big Book of Large-Cast Plays SCENE 1 TIME: Summer, 1920. 1 SETTING: Study in James Hughes’s home near Mexico City. A desk, chair, and wastebasket are center. Accountant’s ledger lies closed on edge of desk. Floor vase with tall pampas grass stands nearby. 2 AT RISE: LANGSTON HUGHES sits writing at desk. SEÑORA GARCIA enters, holding feather duster. 3 SEÑORA GARCIA: Señor Langston, how can you sit in one place for hours just writing? 4 LANGSTON (Leaning back): Señora Garcia, if I could spend my whole life writing, I’d be happy. 5 SEÑORA GARCIA (Dusting vase): You are a true artist, Señor Langston. (Turns; sighs) It is too bad that your father does not understand. You two belong to different worlds. You are a dreamer, and he is such a practical man. (Door slams off) . Go On Assessment 2 69 ©Curriculum Associates, LLC Copying is not permitted. 6 (MR. HUGHES enters, frowning.) 7 SEÑORA GARCIA (Turns with big smile): Buenas días, Señor Hughes. We were not expecting you back from Toluca so soon. 8 MR. HUGHES: Hello, Señora Garcia. (As he removes his poncho) Langston? 9 LANGSTON (Rising; uncomfortably): Hello, Father. (MR. HUGHES gives poncho to SEÑORA GARCIA, who exits with it.) 10 MR. HUGHES: Well, Langston, let me see what progress you’ve made with the accounting problems. -

How Steve Reich's Music Has Influenced Pat Metheny's and Lyle Mays' the Way Up

The Art of Composing: How Steve Reich's music has influenced Pat Metheny's and Lyle Mays' The Way Up A research into the history of composition techniques By Benjamin van Bruggen August 2014 1 \\\\\\\\\Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Emile Wennekes Dr. Eric Jas Contents Table of Illustrations 3 Table of Tables 4 \\\\\\\\\ABSTRACT 5 \\\\\\\\\INTRODUCTION 7 \\\\\\\\\PREFACE 13 CHAPTER A) PULSING REPEATED NOTES 21 Electric Counterpoint and Reich's compositional practice 21 As characteristic of The Way Up 24 CHAPTER B) THE PHASE SHIFTING TECHNIQUE 31 CHAPTER C) HARMONIC LANGUAGE 39 2 Piano and trumpet solo 40 The harmonic aspects of The Way Up’s main theme 42 CONCLUSION 53 \\\\\\\\\BIBLIOGRAPHY 56 \\\\\\\\\APPENDIX 1 58 Table of Illustrations Figure 1: The Way Up's lead-sheet's cover (Forsyth n.d.). 6 Figure 2: The Way Up's CD release has six different cover designs (AIGA Design Archives n.d.). 8 Figure 3: The Way Up's CD release's booklet (AIGA Design Archives n.d.). 11 Figure 4: Excerpt from Electric Counterpoint's score: bars 63-67 (silent parts not incorporated) (Reich 1987). 20 Figure 5: Pulsing repeated notes in The Way Up's opening measures (Metheny n.d.) 22 Figure 6: Pulsing repeated notes in The Way Up's opening measures (Metheny n.d.) 23 Figure 7: Pulsing repeated notes in The Way Up's opening measures (Metheny n.d.) 24 Figure 8: A scalar arpeggiating figure in the piano is added to the pulsing repeated notes played by the guitar (Metheny n.d.). 26 Figure 9: Reduction of harmonies and pulsing repeated notes in measures 1445-1516 (Metheny n.d.). -

ICMC 2009 Proceedings

Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC 2009), Montreal, Canada August 16-21, 2009 THE PRE-PRODUCTION PROCESS OF NEW YORK COUNTERPOINT FOR CLARINET AND TAPE WRITTEN BY STEVE REICH Amandine Pras, François-Xavier Féron McGill University School of Information Studies Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology (CIRMMT) Kaïs Demers Université de Montréal Faculté de musique Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology (CIRMMT) ABSTRACT the concept that “programming the instrument with the objective of making new sounds is now a part of the New York Counterpoint for clarinet and tape (1985) is a musician’s work, whether as composer or interpreter”1 [7]. mixed music composition, without electronic treatment, in In practice, the live performance becomes only a small which the interpreter records all the parts himself. We element of the entire production process. Consequently, analyzed the compositional processes of this 3-movement the quality of the final output will depend on the work using repetitive motifs and resulting patterns. Then, performer’s understanding of the work in its entirety, we designed the sound system for the performance by which may encourage him or her to collaborate with a taking into consideration the structure and the composition technical team right from the beginning of the project. of the piece, as well as the performer’s requests. Our In the same way that “a recording can’t be a transparent spatialization and recording choices aim to emphasize process” [8] to present music, all the technical choices resulting melodies for each section of the piece, as well as affect the artistic quality of a mixed music concert. -

(“Agreement”) Covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS

INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS TELEVISION PROGRAMS and OTHER PRODUCTION between The WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA (the “Guild”) and The CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION (“CMPA”) and ASSOCIATION QUÉBÉCOISE DE LA PRODUCTION MÉDIATIQUE (“AQPM”) (the “Associations”) March 16, 2015 to December 31, 2017 © 2015 WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA and CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION and the ASSOCIATION QUÉBÉCOISE DE LA PRODUCTION MÉDIATIQUE. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A: General – All Productions p. 1 Article A1 Recognition, Application and Term p. 1 Article A2 Definitions p. 4 Article A3 General Provisions p. 14 Article A4 No Strike and Unfair Declaration p. 15 Article A5 Grievance Procedures and Resolution p. 16 Article A6 Speculative Writing, Sample Pages and Unsolicited Scripts p. 22 Article A7 Copyright and Contracts; Warranties, Indemnities and Rights p. 23 Article A8 Story Editors and Story Consultants p. 29 Article A9 Credits p. 30 Article A10 Security for Payment p. 41 Article A11 Payments p. 43 Article A12 Administration Fee p. 50 Article A13 Insurance and Retirement Plan, Deductions from Writer’s Fees p. 51 Article A14 Contributions and Deductions from Writer’s Fees in the case of Waivers p. 53 Section B: Conditions Governing Engagement p. 54 Article B1 Conditions Governing Engagement for all Program Types p. 54 Article B2 Optional Bibles, Script/Program Development p. 60 Article B3 Options p. 61 Section C: Additional Conditions and Minimum Compensation by Program Type p. 63 Article C1 Feature Film p. 63 Article C2 Optional Incentive Plan for Feature Films p. 66 Article C3 Television Production (Television Movies) p. -

The Pleasure of the Intertext: Towards a Cognitive Poetics of Adaptation

!1 THE PLEASURE OF THE INTERTEXT: TOWARDS A COGNITIVE POETICS OF ADAPTATION A dissertation presented by Meg Tarquinio to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April, 2017 !2 THE PLEASURE OF THE INTERTEXT: TOWARDS A COGNITIVE POETICS OF ADAPTATION by Meg Tarquinio ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April, 2017 !3 ABSTRACT The field of adaptation studies has been diagnosed as lacking consensus around its main tenets, especially those that would build a strong ontological foundation. This study participates in the burgeoning critical approach that places cognitive science in conversation with literary theory, looking towards the start of a cognitive turn in adaptation studies. Specifically, I offer the axiom that adaptations are analogies. In other words, I advance the original argument that adaptations are the textual expression of the cognitive function of analogy. Here, I’m using a cognitive theory of analogy as the partial mapping of knowledge (objects and relations) from a source domain to a target domain. From this vantage point, I reassess the theoretical tensions and analytical practices of adaptation studies. For instance, the idea of essence is an anathema within academic studies of adaptation, yet it continues to hold sway within popular discourse. My approach allows for a productive return to essence, not as some mystical quality inherent in an original text and then indescribably transmitted to its adaptation, but as the expression of a key sub-process of analogical reasoning – what Douglas Hofstadter refers to, conveniently, as “essence” or “gist extraction.” This line of argument demonstrates the degree to which André Bazin’s 1948 theorization of adaptation is in line with this cognitive version of essence. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality.