The Pleasure of the Intertext: Towards a Cognitive Poetics of Adaptation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Christian Concerns to Sexuality in Action : a Study of D.H

81blroth&~uenationale CANADIAN THES'ES ?)/~sESCANADIENNES d Canada ON MICROFICHE SUR MICROFICHE hAVE 6~ALITHW NOM DE L'AUTEUR TITLE OF THESIS TITRE DE LA TH~SE . L-7 Perm~ssron IS heray grmted to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF L'autorlsar~onest, par la prdsente, accordge B /a BIBLIOTHS. CANADA to mtcrof~lrn th~sthes~s and to lend or sell copies QUE NATlONALE DU CANADA de m~crof~lme~certe these et of the film, de prgter ou de vendre des exemplaires du film. Th'e auth~rreservss othef publication rights, and neither the L'auteur se rbserve Ies aulres droits de publication. ?I la t'lesls nw extensive extracts from it may be printed or other- th$seni,de longs extraits de celle-CI nedoivent drre itnprirnt!~ wlse reproduced without the author's written perrniss~on. ov autrement reprcrduits sani l'autorisatian Pcrite de /'auteur. C DATED DAT~ Natlonal L~braryof Canada Bibl1oth6quenationale du Canada Collect~onsDevelopment Branch Direction du developpement des collections , Canad~anTheses on Service des thBses canadiennes '- Microfiche Service sur microfiche The quality of this microfiche is heavily dependent La qualite de cette microfiche depend grandement de upon the quality of the original thesis submitted for la qualite de la these soumise au microfilmage. Nous microfilming. Every , effort has been made to ensure 'avons tout fait pour assurer une qualite supkrieure the highest quality of reproduction possible. de reproduction. If pages are missing, contact the university which S'il manque des pages, veuillez communiquer granted the degree. avec I'universite qui a confer@le grade. -

LCO Jonny Greenwood Feb FINAL HB

For immediate release Jonny Greenwood and the London Contemporary Orchestra Soloists in concert Sunday 23 February 2014 Wapping Hydraulic Power Station, E1W PerFormance at 7:30pm Tickets: £28 (incl. booking fee) www.lcorchestra.co.uk Guitarist and acclaimed composer Jonny Greenwood is once again joining forces with the London Contemporary Orchestra (LCO) to present a special one-off performance featuring music from his catalogue of film scores as well as a showcase of new material by Greenwood, at the Wapping Hydraulic Power Station in East London, Sunday 23 February 2014. Greenwood will appear alongside the LCO Soloists playing guitar, electronics and the Ondes Martenot. In addition to music by Greenwood, which includes cues from his scores for the Oscar and BAFTA-nominated films There Will Be Blood and The Master, and Japanese film Norwegian Wood based on the book by Haruki Murakami, the concert features works by J.S. Bach, Henry Purcell and contemporary British composer Edmund Finnis. This performance will mark a continued creative relationship between the London Contemporary Orchestra and Jonny Greenwood. The LCO has been performing Greenwood’s orchestral works since 2008 and this concert, curated by Greenwood and the LCO’s Artistic Directors Hugh Brunt and Robert Ames, will be the second major collaboration between the composer and orchestra since the LCO performed and recorded the score for the lauded 2012 film The Master, directed by Paul Thomas Anderson and starring Philip Seymour Hoffman and Joaquin Phoenix. Since 2003 Greenwood has become well known for his work as a film composer, and has scored five major films, including Bodysong, There Will Be Blood, We Need To Talk About Kevin, Norwegian Wood and The Master. -

The Art of Adaptation

Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Bókmenntir, Menning og Miðlun The Art of Adaptation The move from page to stage/screen, as seen through three films Margrét Ann Thors 301287-3139 Leiðbeinandi: Guðrún Björk Guðsteinsdóttir Janúar 2020 2 Big TAKK to ÓBS, “Óskar Helps,” for being IMDB and the (very) best 3 Abstract This paper looks at the art of adaptation, specifically the move from page to screen/stage, through the lens of three films from the early aughts: Spike Jonze’s Adaptation, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman, or The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance, and Joel and Ethan Coen’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? The analysis identifies three main adaptation-related themes woven throughout each of these films, namely, duality/the double, artistic madness/genius, and meta- commentary on the art of adaptation. Ultimately, the paper seeks to argue that contrary to common opinion, adaptations need not be viewed as derivatives of or secondary to their source text; rather, just as in nature species shift, change, and evolve over time to better suit their environment, so too do (and should) narratives change to suit new media, cultural mores, and modes of storytelling. The analysis begins with a theoretical framing that draws on T.S. Eliot’s, Linda Hutcheon’s, Kamilla Elliott’s, and Julie Sanders’s thoughts about the art of adaptation. The framing then extends to notions of duality/the double and artistic madness/genius, both of which feature prominently in the films discussed herein. Finally, the framing concludes with a discussion of postmodernism, and the basis on which these films can be situated within the postmodern artistic landscape. -

The BG News December 12, 2003

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 12-12-2003 The BG News December 12, 2003 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News December 12, 2003" (2003). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7211. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7211 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Bowling Green State University FRIDAY December 12, 2003 HOCKEY: BG hockey takes on PARTLY CLOUDY Findlay, looking to break HIGH: 31 I LOW: 18 their winless streak www.hgnews.com A daily independent student press VOLUME 98 ISSUE 71 before holiday; PAGE 5 NEWS Third Ohio 'Pif open on Wooster By Monica Frost then choose between a selection a.m. to 3 a.m. Thursday through University. "It's a healthy alter- . REPORICO of fresh meat or vegetarian Saturday from 11 a.m. to 4 a.m. native to fast food," Paglio said. Watch out local sandwich options. Customers can also and Sunday from noon until 3 "Everything is so fresh - I just shops — there's a new kid on the customize their pita selection a.m. love them." block. with cheeses, vegetable top- Stein said he believes The Pita The Pita Pit has 11 pitas under ". -

Book 5 – Into My Mortal – the Poetry of Allison

Into My Mortal Allison Grayhurst Edge Unlimited Publishing 2 Into My Mortal Copyright © 2004 by Allison Grayhurst First addition All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage, retrieval and transmission systems now known or to be invented without permission in writing from the author, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Cover Art (sculpture): “Girl” © 2012 by Allison Grayhurst Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Grayhurst, Allison, 1966- Into My Mortal “Edge Unlimited Publishing” Poems. ISBN-13: 978-1478228585 ISBN-10: 147822858X Into My Mortal by Allison Grayhurst Title ID: 3934892 3 Table of Contents New Era 7 Vacant Underground 8 SomeOne New 9 I Do Not Try To Understand 10 Under My Skin 11 Corner of a Dream 12 In The Name 13 New Tree in the Garden 14 Hard Pressed 15 Interlude 16 Only One 17 Six Months Pregnant 18 For Life 19 Kind Escape 20 Pulled from the Lifeless Waters 21 Hard As Cain 22 One Little Heart 23 Looking At Pictures 24 Storm 25 Listening to the Talk 26 Pure and Plastic 27 Born 28 How Lucky I Am 29 In Doubt 30 Hard Time Singing 31 Hood 32 Out From Under 33 No Direction 34 I Know That 35 Until The Ladder Shows 36 New House 37 Tribe 38 Flies 39 4 Still 40 Every Height I Fall 41 Legacy 42 Serpent in my Shoe 43 On this Dock 44 Thinking Outside 45 I Long To Know 46 Mustard Seed 47 This Vision In Hiding 48 Overpass 49 I see the things 50 I Sleep In The Rain -

Download Zip Albums Freeorrent Marques Houston, MH ##TOP## Full Album Zip

download zip albums freeorrent Marques Houston, MH ##TOP## Full Album Zip. marques houston, marques houston wife, marques houston net worth, marques houston age, marques houston wife age, marques houston songs, marques houston movies, marques houston and omarion, marques houston brother, marques houston height, marques houston group. DOWNLOAD. Действия. Singer, songwriter, and actor who started out in Immature/IMx but later topped the R&B charts with his solo work. Read Full Biography. Artist Information . Jump to Studio albums — Mr. Houston. Released: September 29, 2009; Label: MusicWorks, Fontana; Formats: CD, digital download. 62, 12. Mattress Music.. Marques Houston, MH Full Album Zip. Listen to Marques Houston in full in the Spotify app.Naked (Explicit Version) By Marques Houston.. 7 Th ng 4 Download Marques Houston Mh Album Free. marques houston mh . houston veteran zip, marques houston mattress music album download zip. Download Full Album, Download Marques Houston - . Marques Houston - Mattress Music Free Torrent, . veteran.zip mediafire 41.28 mb . Free download Marques Houston Mp3. We have about 30 mp3 files ready to play and download. To start this . Full discography of Marques Houston. Marques . Marques Houston Mr Houston Download Zip - issuu.com.. MH's BEST album, period! This is one of those timeless albums that you just have to have if your a R&B fan (specially 90's BORN). Marques Houston is Really 1 . Veteran | Marques Houston to stream in hi-fi, or to download in True CD Quality . of the songwriting and production work is greater than that of Naked and MH.. Houston, Marques : Veteran CD. $5.00 . Marques Houston : Naked (Clean Version) [us Import] CD (2005). -

FRIEDA LAWRENCE and HER CIRCLE Also by Harry T

FRIEDA LAWRENCE AND HER CIRCLE Also by Harry T. Moore THE PRIEST OF LOVE: A LIFE OF D. H. LAWRENCE THE COLLECTED LETTERS OF D. H. LAWRENCE (editor) HENRY JAMES AND HIS WORLD (with F. W. Roberts) E. M. FORSTER THE WORLD OF LAWRENCE DURRELL (editor) SELECTED LETTERS OF RAINER MARIA RILKE (editor) Frieda Lawrence, by the late Charles McKinley FRIEDA LAWRENCE AND HER CIRCLE Letters from, to and about Frieda Lawrence edited by Harry T. Moore and Dale B. Montague ©Harry T. Moore and Dale B. Montague 1981 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1981 978·0·333·27600·6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1981 fly THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-05036-9 ISBN 978-1-349-05034-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-05034-5 Contents Frieda Lawrence frontispiec~ Acknowledgements VI Introduction Vll 1. Letters between Frieda Lawrence and Edward W. Titus 1 2. Letters between Frieda Lawrence and Caresse Crosby 38 3. Letters from Frieda Lawrence and Ada Lawrence Clarke to Martha Gordon Crotch 42 4. Letters from Angelo Ravagli to Martha Gordon Crotch 71 5. Letters between Frieda Lawrence and Richard Aldington 73 Epilogue 138 Index 140 v Acknowledgements Our first acknowledgement must go to Mr Gerald Pollinger, Director of Laurence Pollinger Ltd, which deals with matters concerned with the Lawrence Estate. When Mr Pollinger iearned of the existence of the letters included in this volume, he suggested that they be prepared for publication. -

Illinois Wesleyan University IWU Student Senate Names New President

January 16, 2009 Athergus VOLUME 115 | ISSUE 12 Illinois Wesleyan University IWU Student Senate names new president NICOLE TRAVIS Afolabi, Jedrzejczak or junior STAFF REPORTER presidential candidate Emily Vock earned a majority of votes as After four elections and a three- required by the election code. week lag in notifying the student Because Afolabi and Vock had body, Student Senate named jun- received the most votes, ior Babawande Afolabi the 2009- Jedrzejczak was removed from the 2010 president. race and a run-off election ended “I was humbled,” Afolabi said in Afolabi’s favor. Sophomore of his win. “Looking back three or Matt Hastings, who ran uncontest- four years ago, I was back in ed, won the title of vice president. Nigeria, and then to be named the “After we had the second run- Student Senate president of a fine ning of the election and it went institution like this? It’s unbeliev- into the run-off, I felt a little bit able.” happy because that showed that But for Afolabi, the victory fol- there was nothing like a name MIKE WHITFIELD/THE ARGUS lowed several complications. advantage [from the large publici- Above: Babwande Afolabi, the recent Student Senate President-elect, speaks at the Student Senate During the initial election peri- ty materials],” Afolabi said. “If debates last November. Afolabi won the position after four elections were held. od, Student Senate received an there were a name advantage, I anonymous complaint against probably should have won out- Afolabi and junior presidential right.” candidate Casey Jedrzejczak for The counts for all election votes Normal Police apprehend Shepard publicity materials exceeding the were withheld due to Student size limit defined in the Senate Senate policy. -

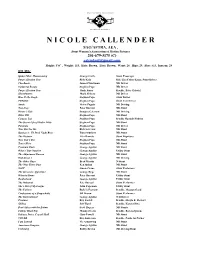

N I C O L E C a Ll E N D

N I C O L E C A LL E N D E R SAG/AFTRA, AEA , Stunt Woman’s Association of Motion Pictures 201-679-3175 (C) [email protected] Height: 5’0” , Weight: 115, Hair: Brown, Eyes: Brown, Waist: 28, Hips: 29, Shoe: 6.5, Inseam: 29 FILMS: Spider-Man: Homecoming George Cottle Stunt Passenger Purge: Election Year Rick Kain Dbl. Lisa Colon-Zayas, Stunt Driver Checkmate James Chuckman ND Driver Collateral Beauty Stephen Pope ND Driver Purge: Election Year Hank Amos Double, Betty Gabriel Ghostbusters Mark Fichera ND Driver How To Be Single Stephen Pope Stunt Driver PRESTO Stephen Pope Stunt Taxi Driver Annie Victor Paguia ND Driving Non-Stop Peter Bucossi ND Stunt Winter’s Tale Douglas Coleman ND Driving Bitter Pill Stephen Pope ND Stunt Campus Life Stephen Pope Double Hannah Hodson The Secret Life of Walter Mitty Stephen Pope ND Stunt Paranoia Stephen Pope ND Driver Now You See Me Rick Lefevour ND Stunt Batman 3: Th Dark Night Rises Tom Struthers ND Stunt The Dictator Alex Daniels Stunt Dignitary New Year’s Eve Stephen Pope ND Stunt Tower Heist Stephen Pope ND Stunt Premium Rush George Aguilar ND Stunt What’s Your Number George Aguilar Utility Stunt The Adjustment Bureau George Aguilar ND Stunt Wall Street 2 George Aguilar ND Driving The Other Guys Brad Martin N/Stunt The Next Three Days Ken Quinn ND Stunt SALT Simon Crane Stunt Performer The Sorcerers Apprentice George Ruge ND Stunt When in Rome Peter Bucossi Utility Stunt Zombieland George Aguilar Utility Stunt The Rebound Pete Bucossi Stunt Performer She’s Out of My League John Copeman Utility Stunt The Unborn Rick LeFeavour Double, Meagan Good Confessions of a Shopacholic Jill Brown Stunt Performer The International George Aguilar N/D Driver Precious Roy Farfell Double, Shayla E. -

Hyperreality in Radiohead's the Bends, Ok Computer

HYPERREALITY IN RADIOHEAD’S THE BENDS, OK COMPUTER, AND KID A ALBUMS: A SATIRE TO CAPITALISM, CONSUMERISM, AND MECHANISATION IN POSTMODERN CULTURE A Thesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Attainment of the Sarjana Sastra Degree in English Language and Literature By: Azzan Wafiq Agnurhasta 08211141012 STUDY PROGRAM OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS YOGYAKARTA STATE UNIVERSITY 2014 APPROVAL SHEET HYPERREALITY IN RADIOHEAD’S THE BENDS, OK COMPUTER, AND KID A ALBUMS: A SATIRE TO CAPITALISM, CONSUMERISM, AND MECHANISATION IN POSTMODERN CULTURE A THESIS By Azzan Wafiq Agnurhasta 08211141012 Approved on 11 June 2014 By: First Consultant Second Consultant Sugi Iswalono, M. A. Eko Rujito Dwi Atmojo, M. Hum. NIP 19600405 198901 1 001 NIP 19760622 200801 1 003 ii RATIFICATION SHEET HYPERREALITY IN RADIOHEAD’S THE BENDS, OK COMPUTER, AND KID A ALBUMS: A SATIRE TO CAPITALISM, CONSUMERISM, AND MECHANISATION IN POSTMODERN CULTURE A THESIS By: AzzanWafiqAgnurhasta 08211141012 Accepted by the Board of Examiners of Faculty of Languages and Arts of Yogyakarta State University on 14July 2014 and declared to have fulfilled the requirements for the attainment of the Sarjana Sastra degree in English Language and Literature. Board of Examiners Chairperson : Nandy Intan Kurnia, M. Hum. _________________ Secretary : Eko Rujito D. A., M. Hum. _________________ First Examiner : Ari Nurhayati, M. Hum. _________________ Second Examiner : Sugi Iswalono, M. A. _________________ -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

Radiohead and the Philosophy of Music

1 Radiohead and the Philosophy of Music Edward Slowik There’s an old joke about a stranger who, upon failing to get any useful directions from a local resident, complains that the local “doesn’t know much.” The local replies, “yeah, but I ain’t lost”. Philosophers of music are kind of like that stranger. Music is an important part of most people’s lives, but they often don’t know much about it—even less about the philosophy that underlies music. Most people do know what music they like, however. They have no trouble picking and choosing their favorite bands or DJs (they aren’t lost). But they couldn’t begin to explain the musical forms and theory involved in that music, or, more importantly, why it is that music is so important to them (they can’t give directions). Exploring the evolution of Radiohead’s musical style and its unique character is a good place to start. Radiohead and Rock Music In trying to understand the nature of music, it might seem that focusing on rock music, as a category of popular music, is not a good choice. Specifically, rock music complicates matters because it brings into play lyrics, that is, a non-musical written text. This aspect of rock may draw people’s attention away from the music itself. (In fact, I bet you know many people who like a particular band or song based mainly on the lyrics—maybe these people should take up poetry instead!) That’s why most introductions to the philosophy of music deal exclusively with classical music, since classical music is often both more complex structurally and contains no lyrics, allowing the student to focus upon the purely musical structural components.