Forgotten Wrecks: Shipwrecks of the Channel Crossing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gommunigator

e(s yb :- ::-: ' -a'+===--:-:: THE GOMMUNIGATOR FieldMarshal, The Lotd Maior-Gelerat, The ViscoEnt Eardtng of Petherton Moncktoa of Erencbley .Es a mernber of the Services liable to constant moves, you have a greater than average need for the professional co-ordination of your afrairs. Sausmarez Carey & Harris are a group of experts who between them have experience in all aspects of financial planning for the individual. They are able to assess the overall situation, taking into account financial and family background. They then proceed to advise on future overall strategy aimed at achieving most effi,ciently and economically these objectives. If you would like to establish a notional btueprint of your overdl position, and plan successfully and flexibly for the future, we are will profit frorn a ::ilil\?i,[o" SAUSMAREZ GANDY& HANRIS IIMITEID 419 Oxford Street, WlR ?llP. tel: 0I-499 7000 65 London \tr/all, EC2M 5UA. tel : 0I -499 7000 - lipecialists in Investment, Personal Portfolio Manaqement, Estate Dut'7 an'J Tax 1,1-:l r-:. :. --.i .:-:,. -r .:.1 Mortgaqes, Loans, Pensicns, General Insurance, Overseas Investment arl T..:.:=.:--:- l:-s:s. THE COMMUNICATOR PUBLISHED AT HMS 'MERCURY' The Magazine of the Communications Branch, Royal Navy ani the Royal Naval Amateur Radio Society SPRING-SUMMER 1974 VOL 22, No'l Price: 25p. post free CONT ENT S paSe pugc E orroRrnr I Monsr ,qllo \lonsr TRarNrNc il CaprerN R. D. FReN<Lrr, nu 1 Wcro Pi,nr ll RouNo rnp Wonlo RacE 4 \4ror l\4aro lll 11 SpRlNc Cnosswono 6 GorNc rHe RouxDS rN MEncuRy 12 WrrerevER F{,a,ppEtr;o ro COA'l 1 Flr.r.r Sccrrox l9 RN Auerr,un R.eoto Socrerv 8 Cora,vl sstoNINC Fonrr'lsr 40 Lr,rrr.Rs ro t{E EorroR 8 Pt:.lu p ++,1 / BrRt'.trNculu RNR l0 CoivvuNicATioNS G tzettr. -

"Weapon of Starvation": the Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2015 A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919 Alyssa Cundy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Cundy, Alyssa, "A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919" (2015). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1763. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1763 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A “WEAPON OF STARVATION”: THE POLITICS, PROPAGANDA, AND MORALITY OF BRITAIN’S HUNGER BLOCKADE OF GERMANY, 1914-1919 By Alyssa Nicole Cundy Bachelor of Arts (Honours), University of Western Ontario, 2007 Master of Arts, University of Western Ontario, 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in History Wilfrid Laurier University 2015 Alyssa N. Cundy © 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the British naval blockade imposed on Imperial Germany between the outbreak of war in August 1914 and the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles in July 1919. The blockade has received modest attention in the historiography of the First World War, despite the assertion in the British official history that extreme privation and hunger resulted in more than 750,000 German civilian deaths. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A. -

Defeating the U-Boat Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare NEWPORT PAPERS

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 36 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Defeating the U-boat Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT S NA N E V ES AV T AT A A A L L T T W W S S A A D D R R E E C C T T I I O O L N L N L L U U E E E E G G H H E E T T I I VIRIBU VOIRRIABU OR A S CT S CT MARI VI MARI VI 36 Jan S. Breemer Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE This perspective aerial view of Newport, Rhode Island, drawn and published by Galt & Hoy of New York, circa 1878, is found in the American Memory Online Map Collections: 1500–2003, of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C. The map may be viewed at http://hdl.loc.gov/ loc.gmd/g3774n.pm008790. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978-1-884733-77-2 is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Govern- ment Printing Office requests that any reprinted edi- tion clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates Defeating the U- boat: Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare, by Jan S. -

A Royal Navy Monitor at Stavros. My Grandfather, Charlie Burgoyne, Was

A Royal Navy Monitor at Stavros. My grandfather, Charlie Burgoyne, was a stoker on the monitor, HMS M18. When I asked him the classic “what did you do in the war Grandad?” he told me that he had been at Gallipoli, and that it was horrible, so I never pursued the matter. After he died, I was given his naval service record, and I have recently discovered that he was based around Salonika and Stavros for almost three years after Gallipoli. I have been consulting the Ship’s Log at the National Archives to find out what his vessel was doing, and I also contacted Alan Wakefield at the Society. He suggested I prepared this note since there is very little written about the naval aspects of the Salonika campaign. Charlie was one of 6 children of George Burgoyne and his wife Lavinia; they lived in the South Devon village of Aveton Gifford. Two of the children had died in infancy, an elder brother was serving with the 2nd Devons, and the two sisters were “in service”. Charlie joined the Navy in January 1909, claiming to be 18 although we suspect he was still only 17. He served as a stoker but on the outbreak of hostilities he was posted to the oil-fired torpedo boat HMS TB5. She had originally been classed as a Torpedo Boat Destroyer but with the development of the larger Destroyer classes, which could sail with the fleet, they were downgraded to roles as Coastal Destroyers. Charlie spent about 6 months based at Immingham, patrolling each day off the mouth of the Humber, but saw no action. -

Dover Blue Trail

Park Street- air raid Park Avenue- Lighting Linton, Park Avenue towards the top of Frith Road site of the Dover Patrol Zeebrugge Bell siren behind the current 99 Barton Rd Igglesden family 67 Barton Rd- Matron Edith Johncock restrictions the Avenue county school for boys 1 2 houses 3 Dover Blue Trail 4 5 6 7 The Dover Patrol was The air raid siren was In 1917 it was reported Agnes Baynham; whose son Cuthbert served with the The County School for Boys Robert and Mary’s Elizabeth vital to keeping the placed on the roof of the that the trunks of the Royal Field Artillery; was a supporter of the Dover moved here in 1916 from the three eldest sons Johncock’s Distance: 3.96 km daughter Edith shipping lanes of the electricity works. It would trees in Park Avenue had Relief Fund for Belgian Refugees. The fund assisted centre of town. Of the past had attended the County School for returned home Channel open during sound 4 short blasts all been whitewashed refugees in this country and also those in France and pupils of the School over 45% followed by one long Boys before serving in 1919 having the First World War. for a height of five feet. (2.46 miles) Belgium with practical help. Refugees could not settle served in the War. The boys dug blast to warn people to However there was no in the War. Henry been held prisoner They also conducted in Dover because of security around the port. up their playing field in 1917 take cover. -

L\ ZEEBRUGGE AFFAIR

l\ ZEEBRUGGE AFFAIR L- Twenty-five cents net. THE ZEEBRUGGE AFFAIR THE ZEEBRUGGE AFFAIR BY KEBLE HOWARD (J. KEBLE BELL, 2ND LIEUT. RA.F.) WITH THE BRITISH OFFICIAL NARRATIVES OF THE OPERATIONS AT ZEEBRUGGE AND OSTEND Exclusive and Official Photographs NEW YORK GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY \ CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. WHAT ZEEBRUGGE AND OSTEND MEAN . 7 II. CAPTAIN CARPENTER IN HIS ATTIC ... 11 III. How THE PLANS WERE LAID 14 IV. THE GREAT FIGHT . 19 V. A MUSEUM IN A TRUNK 26 VI. ON BOARD H.M.S. Vindictive 30 VII. THE MAN WHO PELT FRIGHTENED . .33 VIII. WHAT THE MARINES TOLD THE HUNS . 37 IX. I HEAR THEY WANT MORE 40 BRITISH ADMIRALTY OFFICIAL NARRATIVES: ZEEBRUGGE AND OSTEND—FIRST ATTACK . 43 OSTEND—SECOND ATTACK ..... 55 v CHAPTER I What Zeebrugge and Ostend Mean ET me, first of all, try to tell you the story of L Zeebrugge as I extracted it, not without diffi culty, from several of the leading spirits of that enter prise. This is no technical story. Elsewhere in this little volume you will find the official narrative issued by the Admiralty to the Press, and that contains, as all good official documents do, names, ranks, dates, times, and movements. I lay claim to no such precision. It is my proud yet humble task to bring you face to face, if I can, with the men who went out to greet what they re garded as certain death—bear that in mind—in order to stop, in some measure, the German submarine men ace, and to prove yet once again to all the world that 7 8 The Zeebrugge Affair the British Navy is the same in spirit as it was in the days of Nelson and far down the ages. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

Submarine Wrecks Around the UK

The Historical Archaeology of World War I U-boats and the Compilation of Admiralty History: The Case of (UC-79) Dr. Innes McCartney Bournemouth University, Dept. of Applied Sciences Fern Barrow, Poole, Dorset BH12 5BB, UK [email protected] Over the course of the last 17 years the author has researched, dived, surveyed and identified some 100 submarine wrecks around the UK. His 2014 book examines the 63 known U-boat wrecks in the English Channel, of which 32 were sunk during World War I. Detailed analysis of each case revealed that the list of U-boat losses published by the Antisubmarine Division (ASD) of the Admiralty in 1919 (the 1919 List) was only 48 per cent accurate. Of the wrecks not mentioned in the 1919 List, (UC-79) is the most startling case, primarily because ASD knew where it was during wartime but hid its true fate when it compiled the 1919 List in order to preserve its own reputation. This paper examines why this happened and what its broader implications are for archaeologists, historians and heritage managers. The 1917-18 Dover Barrage with U-Boat wrecks and incedents Matching U-boat Wrecks WWI Dived U-boat wrecks Mystery U-boat Wrecks 1919 List of U-boat losses Dover Patrol Incedents Dover Barrage ASD Incedents (Submarine) (UC79) Oil patch reported 12 June 1918 7 August 1918 dive site U109 UC61 N W E S Gris Nez 0 2 4 Nautical Miles Figure 1. Map showing the location of the wreck of (UC79) in the Dover Barrage and the related oil patch and 1918 diving site. -

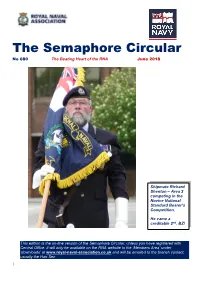

The Semaphore Circular No 680 the Beating Heart of the RNA June 2018

The Semaphore Circular No 680 The Beating Heart of the RNA June 2018 Shipmate Richard Shenton – Area 3 competing in the Novice National Standard Bearer’s Competition. He came a creditable 2nd. BZ! This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Daily Orders (follow each link) Orders [follow each link] 1. National Standard Bearers Competition 2. RNVC Commander Robert Ryder VC 3. Joke – Another old Golfing 4. Charity Donations 5. Guess Where 6. RM Band Scotland Belfast Charity Concert 7. Hospital and Medical Care Association 8. Conference 2019 9. Military Veterans – Burnley FC 10. RNAS Yeovilton Air Day 11. Royal Navy Catering Services Recruitment 12. Can you Assist – S/M Tim Jarvis 13. OAP Alphabet 14. RN Shipmates Information Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy General Secretary AGS Assistant General Secretary CONA Conference of Naval Associations Throughout indicates a new or substantially changed entry Contacts Financial Controller 023 9272 3823 [email protected] Digital Media Assistant [email protected] Deputy General Secretary 023 -

Men of Burgess Hill 1939-1946

www.roll-of-honour.com The Men of Burgess Hill 1939 to 1946 Remembering the Ninety who gave their lives for peace and freedom during the Second World War By Guy Voice Copyright © 1999-2004 It is only permissible for the information within The Men Burgess Hill 1939-46 to be used in private “not for profit” research. Any extracts must not be reproduced in any publication or electronic media without written permission of the author. "This is a war of the unknown warriors; but let all strive without failing in faith or in duty, and the dark curse of Hitler will be lifted from our age." Winston Churchill, broadcasting to the nation on the BBC on 14th July 1940. Guy Voice 1999-2004 1 During the Second World War the Men of Burgess Hill served their country at home and in every operational theatre. At the outset of the war in 1939, young men across the land volunteered to join those already serving in the forces. Those who were reservists or territorials, along with many, who had seen action in the First World War, joined their units or training establishments. The citizens of Burgess Hill were no different to others in Great Britain and the Commonwealth as they joined the Royal Navy, Army and Royal Air Force in large numbers. Many more of the townspeople did valuable work on the land or in industry and, living close to the sea some served in the Merchant Navy. As the war continued many others, women included, volunteered or were called up to “do their bit”. -

Admiral Roger Keyes and Naval Operations in the Littoral Zone A

Admiral Roger Keyes and Naval Operations in the Littoral Zone A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Harrison G. Fender May 2019 ©2019 Harrison G. Fender. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Admiral Roger Keyes and Naval Operations in the Littoral Zone by HARRISON G. FENDER has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Peter John Brobst Associate Professor of History Joseph Shields Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT Fender, Harrison G., M.A., May 2019, History Admiral Roger Keyes and Naval Operations in the Littoral Zone Director of Thesis: Peter John Brobst Since the second decade of the twenty-first century the littoral has been a zone of international tension. With the littoral the likely center of future naval engagements, it is important to remember that the issues of today are not new. Admiral Roger Keyes of the Royal Navy also had to contend with operating in contested littoral zones protected by anti-access weapons. Keyes’ solution to this was the integration of the latest weapons and techniques to overcome enemy defenses. By doing so, Keyes was able to project power upon a region or protect sea lines of communication. This thesis will examine the naval career of Roger Keyes during and between the First and Second World Wars. It will discuss that, through wartime experience, Keyes was aware of the trends in naval operations which led him to modernize the Royal Navy.