HE Name "Mediterranean" Suggests the Importance of the Sea That T Bears It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telling the Story of the Royal Navy and Its People in the 20Th & 21St

NATIONAL Telling the story of the Royal Navy and its people MUSEUM in the 20th & 21st Centuries OF THE ROYAL NAVY Storehouse 10: New Galleries Project: Exhibition Design Report JULY 2011 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE ROYAL NAVY Telling the story of the Royal Navy and its people in the 20th & 21st Centuries Storehouse 10: New Galleries Project: Exhibition Design Report 2 EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT Contents Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 2.0 Introduction 2.1 Vision, Goal and Mission 2.2 Strategic Context 2.3 Exhibition Objectives 3.0 Design Brief 3.1 Interpretation Strategy 3.2 Target Audiences 3.3 Learning & Participation 3.4 Exhibition Themes 3.5 Special Exhibition Gallery 3.6 Content Detail 4.0 Design Proposals 4.1 Gallery Plan 4.2 Gallery Plan: Visitor Circulation 4.3 Gallery Plan: Media Distribution 4.4 Isometric View 4.5 Finishes 5.0 The Visitor Experience 5.1 Visuals of the Gallery 5.2 Accessibility 6.0 Consultation & Participation EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT 3 Ratings from HMS Sphinx. In the back row, second left, is Able Seaman Joseph Chidwick who first spotted 6 Africans floating on an upturned tree, after they had escaped from a slave trader on the coast. The Navy’s impact has been felt around the world, in peace as well as war. Here, the ship’s Carpenter on HMS Sphinx sets an enslaved African free following his escape from a slave trader in The slave trader following his capture by a party of Royal Marines and seamen. the Persian Gulf, 1907. 4 EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT 1.0 Executive Summary 1.0 Executive Summary Enabling people to learn, enjoy and engage with the story of the Royal Navy and understand its impact in making the modern world. -

The Vietnam War an Australian Perspective

THE VIETNAM WAR AN AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE [Compiled from records and historical articles by R Freshfield] Introduction What is referred to as the Vietnam War began for the US in the early 1950s when it deployed military advisors to support South Vietnam forces. Australian advisors joined the war in 1962. South Korea, New Zealand, The Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand also sent troops. The war ended for Australian forces on 11 January 1973, in a proclamation by Governor General Sir Paul Hasluck. 12 days before the Paris Peace Accord was signed, although it was another 2 years later in May 1975, that North Vietnam troops overran Saigon, (Now Ho Chi Minh City), and declared victory. But this was only the most recent chapter of an era spanning many decades, indeed centuries, of conflict in the region now known as Vietnam. This story begins during the Second World War when the Japanese invaded Vietnam, then a colony of France. 1. French Indochina – Vietnam Prior to WW2, Vietnam was part of the colony of French Indochina that included Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Vietnam was divided into the 3 governances of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. (See Map1). In 1940, the Japanese military invaded Vietnam and took control from the Vichy-French government stationing some 30,000 troops securing ports and airfields. Vietnam became one of the main staging areas for Japanese military operations in South East Asia for the next five years. During WW2 a movement for a national liberation of Vietnam from both the French and the Japanese developed in amongst Vietnamese exiles in southern China. -

An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

An analysis of the loss of HMAS SYDNEY By David Kennedy The 6,830-ton modified Leander class cruiser HMAS SYDNEY THE MAIN STORY The sinking of cruiser HMAS SYDNEY by disguised German raider KORMORAN, and the delayed search for all 645 crew who perished 70 years ago, can be attributed directly to the personal control by British wartime leader Winston Churchill of top-secret Enigma intelligence decodes and his individual power. As First Lord of the Admiralty, then Prime Minster, Churchill had been denying top secret intelligence information to commanders at sea, and excluding Australian prime ministers from knowledge of Ultra decodes of German Enigma signals long before SYDNEY II was sunk by KORMORAN, disguised as the Dutch STRAAT MALAKKA, off north-Western Australia on November 19, 1941. Ongoing research also reveals that a wide, hands-on, operation led secretly from London in late 1941, accounted for the ignorance, confusion, slow reactions in Australia and a delayed search for survivors . in stark contrast to Churchill's direct part in the destruction by SYDNEY I of the German cruiser EMDEN 25 years before. Churchill was at the helm of one of his special operations, to sweep from the oceans disguised German raiders, their supply ships, and also blockade runners bound for Germany from Japan, when SYDNEY II was lost only 19 days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Southeast Asia. Covering up of a blunder, or a punitive example to the new and distrusted Labor government of John Curtin gone terribly wrong because of a covert German weapon, can explain stern and brief official statements at the time and whitewashes now, with Germany and Japan solidly within Western alliances. -

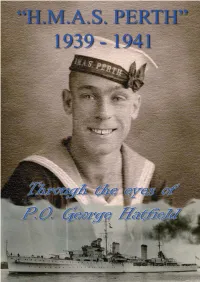

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

Don-Juan Canto III Annotated

Don Juan CANTOÛ III Gordon, Lord Byron Annotations by Peter Gallagher¤ April, 2015 You can find the free audio-book of Canto 1 of Don Juan on the iBooks Store Û ¤ [email protected] Canto 3 I Hail Muse ] Finally, at the start of Canto III, Byron gets around to invoking the Muse: the traditional way to start an Epic poem HAIL, Muse! et cetera.—We left Juan sleeping, and, briefly, to foreshadow its subject. But Byron’s invocation is no Pillowed upon a fair and happy breast, more than a sardonic nod to the idea; a sort of poetic blasphemy. Compare, for example, Homer’s Iliad (first seven lines), or Odyssey And watched by eyes that never yet knew weeping, (first ten lines) or Virgil’s Æneid (first eleven lines). Or, again, And loved by a young heart, too deeply blest Paradise Lost, where Milton’s invocation to his “Heavn’ly Muse” occupies the first twenty-six, breathless, lines. To feel the poison through her spirit creeping, Byron’s first draft of Canto III, before he split it into two Can- Or know who rested there, a foe to rest, tos, began with a nine-verse attack on Wellington; later moved Had soiled the current of her sinless years, to Canto IX. This verse, in that earlier draft, began: “Now to my Epic. ” And turned her pure heart’s purest blood to tears! A foe to rest ] The “foe to rest” refers to the “who” of the previous sentence. It is “Love”, addressed in the next verse, that II rests in her heart and has “soiled the current of [Haidee’s] sinless years. -

Air Force Enlisted Personnel Policy 1907-1956

FOUNDATION of the FORCE Air Force Enlisted Personnel Policy 1907-1956 Mark R. Grandstaff DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited AIR PROGRAM 1997 20050429 034 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grandstaff, Mark R. Foundation of the Force: Air Force enlisted personnel policy, 1907-1956 / Mark R. Grandstaff. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. United States. Air Force-Non-commissioned officers-History. 2. United States. Air Force-Personnel management-History. I. Title. UG823.G75 1996 96-33468 358.4'1338'0973-DC20 CIP For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN 0-16-049041-3 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGEFomApve OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information Is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of Information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. -

On Our Doorstep Parts 1 and 2

ON 0UR DOORSTEP I MEMORIAM THE SECOD WORLD WAR 1939 to 1945 HOW THOSE LIVIG I SOME OF THE PARISHES SOUTH OF COLCHESTER, WERE AFFECTED BY WORLD WAR 2 Compiled by E. J. Sparrow Page 1 of 156 ON 0UR DOORSTEP FOREWORD This is a sequel to the book “IF YOU SHED A TEAR” which dealt exclusively with the casualties in World War 1 from a dozen coastal villages on the orth Essex coast between the Colne and Blackwater. The villages involved are~: Abberton, Langenhoe, Fingringhoe, Rowhedge, Peldon: Little and Great Wigborough: Salcott: Tollesbury: Tolleshunt D’Arcy: Tolleshunt Knights and Tolleshunt Major This likewise is a community effort by the families, friends and neighbours of the Fallen so that they may be remembered. In this volume we cover men from the same villages in World War 2, who took up the challenge of this new threat .World War 2 was much closer to home. The German airfields were only 60 miles away and the villages were on the direct flight path to London. As a result our losses include a number of men, who did not serve in uniform but were at sea with the fishing fleet, or the Merchant avy. These men were lost with the vessels operating in what was known as “Bomb Alley” which also took a toll on the Royal avy’s patrol craft, who shepherded convoys up the east coast with its threats from: - mines, dive bombers, e- boats and destroyers. The book is broken into 4 sections dealing with: - The war at sea: the land warfare: the war in the air & on the Home Front THEY WILL OLY DIE IF THEY ARE FORGOTTE. -

RAN Ships Lost

CALL THE HANDS OCCASIONAL PAPER 6 Issue No. 6 March 2017 Royal Australian Navy Ships Honour Roll Given the 75th anniversary commemoration events taking place around Australia and overseas in 2017 to honour ships lost in the RAN’s darkest year, 1942 it is timely to reproduce the full list of Royal Australian Navy vessels lost since 1914. The table below was prepared by the Directorate of Strategic and Historical Studies in the RAN’s Sea Power Centre, Canberra lists 31 vessels lost along with a total of 1,736 lives. Vessel (* Denotes Date sunk Casualties Location Comments NAP/CPB ship taken up (Ships lost from trade. Only with ships appearing casualties on the Navy Lists highlighted) as commissioned vessels are included.) HMA Submarine 14-Sep-14 35 Vicinity of Disappeared following a patrol near AE1 Blanche Bay, Cape Gazelle, New Guinea. Thought New Guinea to have struck a coral reef near the mouth of Blanche Bay while submerged. HMA Submarine 30-Apr-15 0 Sea of Scuttled after action against Turkish AE2 Marmara, torpedo boat. All crew became POWs, Turkey four died in captivity. Wreck located in June 1998. HMAS Goorangai* 20-Nov-40 24 Port Phillip Collided with MV Duntroon. No Bay survivors. HMAS Waterhen 30-Jun-41 0 Off Sollum, Damaged by German aircraft 29 June Egypt 1941. Sank early the next morning. HMAS Sydney (II) 19-Nov-41 645 207 km from Sunk with all hands following action Steep Point against HSK Kormoran. Located 16- WA, Indian Mar-08. Ocean HMAS Parramatta 27-Nov-41 138 Approximately Sunk by German submarine. -

Ajax New Past up For

H.M.S. Ajax & River Plate Veterans Association NEWSLETTER SEPTEMBER 2012 CONTENTS Chairman/Editor's Remarks Visit to Montevideo Presentation to Frank Burton Archivist Report Membership Secretary Report Missing Royal Navy Life AGM Agenda NEC QUISQUAM NISI AJAX 2. 3. H.M.S. AJAX & RIVER PLATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION. Honorary Freeman of Rhyl CHAIRMAN/SECRETARY ARCHIVIST It is with huge pleasure that I include an article describing NEWSLETTER EDITOR Malcolm Collis the very prestigious honour of becoming an Honorary Peter Danks ‘Glenmorag’ Freeman of Rhyl which was bestowed on Roy Turner. I am 104 Kelsey Avenue Little Coxwell sure that all members of the Association send Roy our Southbourne Faringdon sincere congratulations on this tremendous honour. Emsworth Oxfordshire SN7 7LW Hampshire PO10 8NQ Tel: 01367 240382 From the Daily Post, June 22nd, 2012: Tel: 01243 371947 Mobile: 07736 929641 A retired businessman who has given over 50 years’ service to the [email protected] [email protected] community has become the first Honorary Freeman of Rhyl. The Town Council decided to bestow the honour on 84-year-old Roy TREASURER MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Turner as a ceremony on Wednesday night, under new powers recently Alf Larkin Mrs Judi Collis given to town and community councils. 5 Cockles Way ‘Glenmorag’ Weymouth Little Coxwell, Faringdon Born in Stoke-on-Trent, he moved with his family to Rhyl in 1938 and Dorset DT4 9LT Oxfordshire SN7 7LW attended the local county school. In 1946 he joined Royal Navy cruiser Tel: 01305 775553 Tel: 01367 240382 ship HMS Ajax. Roy Turner [email protected] Mobile: 07736 929641 Back in Rhyl, Mr Turner established a flooring contractors business and he became active in the life [email protected] of the community. -

I Rapporti Della Polonia Con L'italia Risalgono Alla Nascita Stessa Dello Stato Polacco Nel X Secolo E Alla Scelta Allora Operata Del Cristianesimo Occi - Dentale

Tra Polonia e Italia I rapporti della Polonia con l'Italia risalgono alla nascita stessa dello Stato polacco nel X secolo e alla scelta allora operata del cristianesimo occi - dentale. Il latino divenne lingua ufficiale dello stato e l'Italia meta di pel - legrinaggi e di studi. Nel Rinascimento i contatti con l’Italia raggiunsero il loro apice e numerosi letterati, architetti, artisti italiani prestarono la loro opera alla corte reale di Cracovia e alle corti aristocratiche. L’astronomo Copernico, colloquio con Dio . Tra i numerosi giovani della Natio polona che frequenta - rono gli atenei italiani figu - rano: Nicolò Copernico (1473-1543); Jan Kochanow - ski (1530-1584), il più grande poeta del Rinascimento po - lacco, e Maciej Sarbiewski (1595-1640), considerato uno dei massimi poeti in lingua la - tina nell’Europa barocca. Olio su tela di Jan Matejko (1838-1893), Museo dell’Università Jagellonica, Cracovia. Bona Sforza (1494 - 1557), figlia di Gian Gale - azzo Sforza, duca di Milano; duchessa di Bari; moglie del re di Polonia, Sigismondo I (1467- 1548); regina di Polonia. Fu portatrice delle idee e dello spirito umanistico e rinascimentale in Po - lonia, favorì la diffusione dell’arte italiana, dei co - stumi e della cucina. Grazie alla sua presenza a Cracovia le relazioni tra la Polonia e l’Italia si sono notevolmente allargate. Incisione di Niccolò Nelli del 1568, Civica Raccolta delle Stampe “Achille Bertarelli”, Milano. Veduta del castello reale di Varsavia dal sobborgo di Praga . La presenza di artisti italiani si mantiene anche sotto il regno dell’ultimo re di Polonia, Stanisław August Poniatowski, sul trono dal 1764 al 1795. -

The World View of the Anonymous Author of the Greek Chronicle of the Tocco

THE WORLD VIEW OF THE ANONYMOUS AUTHOR OF THE GREEK CHRONICLE OF THE TOCCO (14th-15th centuries) by THEKLA SANSARIDOU-HENDRICKX THESIS submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF ARTS in GREEK in the FACULTY OF ARTS at the RAND AFRIKAANS UNIVERSITY PROMOTER: DR F. BREDENKAMP JOHANNESBURG NOVEMBER 2000 EFACE When I began with my studies at the Rand Afrikaans University, and when later on I started teaching Modern Greek in the Department of Greek and Latin Studies, I experienced the thrill of joy and the excitement which academic studies and research can provide to its students and scholars. These opportunities finally allowed me to write my doctoral thesis on the world view of the anonymous author of the Greek Chronicle of the Tocco. I wish to thank all persons who have supported me while writing this study. Firstly, my gratitude goes to Dr Francois Bredenkamp, who not only has guided me throughout my research, but who has always been available for me with sound advice. His solid knowledge and large experience in the field of post-classical Greek Studies has helped me in tackling Byzantine Studies from a mixed, historical and anthropological view point. I also wish to render thanks to my colleagues, especially in the Modern Greek Section, who encouraged me to continue my studies and research. 1 am indebted to Prof. W.J. Henderson, who has corrected my English. Any remaining mistakes in the text are mine. Last but not least, my husband, Prof. B. Hendrickx, deserves my profound gratitude for his patience, encouragement and continuous support. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible.